Tourmaline Canyon: Surfers Vs. Homeowners During the 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Diego & Surrounding Areas

Welcome Welcome to the University of San Diego! We are happy you are here and we hope that you will soon come to look upon our campus as your second home. Your first three weeks will be very busy. This is normal for anyone coming to live and study in the United States. Cultural diversity is welcomed in our country and on our campus. We hope that you will find both your course of study at USD and the opportunity to engage in cultural exchange to be rewarding and satisfying experiences. This handbook is designed to provide you with information you need to make the transition from your country to the United States a little easier. If you have questions, please visit us at the Office of International Students and Scholars (OISS). We are here to help you. We wish you every success in your academic, social, and cultural endeavors. The OISS Team TABLE OF CONTENTS OISS SERVICES……………………………………………………………………………...3 Check-in / Immigration.…………………………………..…………………4 How to Stay “in Status”....…………………………………………………..6 Communications…………………………………………………..............................9 Mobile Phones….………………………………………………………………9 Local Mobile Phone Companies…...….……………………………...11 Making Overseas Phone Calls………………………………………..…12 Internet Connection………………………………………………………...12 Technical Support...………………………………………………..……...13 Mail/Shipping…….…………………………………………………………...13 Transportation……………………………………………………………………………..14 Bus/Trolley Information..……...……………………………………….. 14 Campus Tram.…………………………………………….......................16 USD Parking Permits……...………..…………………………………....17 Car -

California Sea Lion Interaction and Depredation Rates with the Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Fleet Near San Diego

HANAN ET AL.: SEA LIONS AND COMMERCIAL PASSENGER FISHING VESSELS CalCOFl Rep., Vol. 30,1989 CALIFORNIA SEA LION INTERACTION AND DEPREDATION RATES WITH THE COMMERCIAL PASSENGER FISHING VESSEL FLEET NEAR SAN DIEGO DOYLE A. HANAN, LISA M. JONES ROBERT B. READ California Department of Fish and Game California Department of Fish and Game c/o Southwest Fisheries Center 1350 Front Street, Room 2006 P.O. Box 271 San Diego, California 92101 La Jolla, California 92038 ABSTRACT anchovies, Engraulis movdax, which are thrown California sea lions depredate sport fish caught from the fishing boat to lure surface and mid-depth by anglers aboard commercial passenger fishing fish within casting range. Although depredation be- vessels. During a statewide survey in 1978, San havior has not been observed along the California Diego County was identified as the area with the coast among other marine mammals, it has become highest rates of interaction and depredation by sea a serious problem with sea lions, and is less serious lions. Subsequently, the California Department of with harbor seals. The behavior is generally not Fish and Game began monitoring the rates and con- appreciated by the boat operators or the anglers, ducting research on reducing them. The sea lion even though some crew and anglers encourage it by interaction and depredation rates for San Diego hand-feeding the sea lions. County declined from 1984 to 1988. During depredation, sea lions usually surface some distance from the boat, dive to swim under RESUMEN the boat, take a fish, and then reappear a safe dis- Los leones marinos en California depredan peces tance away to eat the fish, tear it apart, or just throw colectados por pescadores a bordo de embarca- it around on the surface of the water. -

Verbatim Inside

VOLUME 53, ISSUE 18 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2020 WWW.UCSDGUARDIAN.ORG LABOR PHOTOSPORTS: TEASE ?E$"FG#H+1%-# MEN’S VOLLEYBALL GOES HERE IJKK#G&4+20)0# B)2&()#$%&4)20 Sanders has been a vocal proponent of the union’s goals for years. !.##2;A&'K=%#+T=T>=GL; .%#(&$/0($#1'+&$("& The University of California’s largest employment union, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Local 3299, announced their decision to PHOTO BY NAME HERE /GUARDIAN endorse Bernie Sanders for President ahead of California’s CAPTION"...UCSD PREVIEWING was able to Estelle performing at Warren Live 2020 // Photo by Ellie Wang 2020 Democratic Primary on Feb. THEdominate ARTICLE in PAIRED every facet WITH 14. The endorsement comes two ofTHE the PHOTO game TEASE.in the win, FOR weeks before the state’s election day on March 3. EXAMPLEshowing o IFf THEa balanced PHOTO CAMPUS attackWERE onOF oAf BABYense, YOUcrisp In an interview with the Times of San Diego, AFSCME Local WOULDpassing, SAY and “BABIES great team SUCK! !"$'#8)9)9:)20#;<=>)%2#?&&(5)20%2@#+A #B-%1C#D(&.)2 THEY ARE WEAK AND 3299 Executive Vice President chemistry." !"##$%&"##$'(')%&###!"#$%&'!()**'+&$("& Michael Avant explained that the reasoning behind the +38$1/2C##0,H3##ESports, page 16 he Associated Students Office of which focused on a wide range of topics Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion and the including the panelists’ personal involvement endorsement was because of +18I23++##0/-1813+ Black Student Union held an event in with student organization during Black Winter the union’s push for collective *+*,--.##/0121/2##$3,+3 Tremembrance of the ten-year anniversary of and how non-black students can be effective bargaining rights. -

USS Midway Museum Historic Gaslamp Quarter Balboa Park

Approx. 22 Miles Approx. 28 Miles San Diego Zoo Del Mar Legoland Fairgrounds Safari Park Del Mar Beaches DOG FRIENDLY 56 North Beach 5 Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve Hiking Torrey Pines Golf Course 805 Torrey Pines Gliderport University of California San Diego Birch Aquarium at Scripps Westfield UTC Mall La Jolla Shores La Jolla Cove 52 Village of La Jolla SeaWorld USS Midway Historic Gaslamp Balboa Park & Museum Quarter San Diego Zoo Approx. 12 Miles Approx. 15 Miles Approx. 16 Miles Approx. 16 Miles Fun Things To Do Within Walking Distance Torrey Pines Golf Course (0.5 mi) – Perfect your swing at the world renowned Torrey Pines Golf Course, home to two 18-hole championship courses. This public course has a driving range and is open every day until 30 minutes before dusk. Call our Golf Team at 1-800-991-GOLF (4653) to book your tee time. Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve (0.8 mi) – Hike a trail in this beautiful 2,000-acre coastal state park overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Some trails lead directly to Torrey Pines State Beach. Trail maps available at our Concierge Desk. Torrey Pines Gliderport (1.5 mi) – Visit North America's top paragliding and hang gliding location and try an instructional tandem flight. Please call ahead since all flights are dependent on the wind conditions - (858) 452-9858. Fun Things To Do Just a Short Drive Away La Jolla Playhouse (2 mi) – A not-for-profit, professional theatre at the University of California San Diego. See Concierge for current showings. Birch Aquarium (3 mi) – Experience stunning sea life at Birch Aquarium at Scripps Institute of Oceanography. -

CELEBRATE LIKE a Legend Aloha WELCOME to DUKE’S LA JOLLA

CELEBRATE LIKE A legend Aloha WELCOME TO DUKE’S LA JOLLA Few locations in San Diego rival the oceanfront setting of Duke’s La Jolla. Our restaurant offers some of the most spectacular sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean, overlooking La Jolla Cove and La Jolla Shores. Our setting is just the beginning of what makes hosting your event at Duke’s La Jolla a truly memorable occasion. Our beautiful restaurant provides you and your guests with an authentic, nostalgic walk back in time through the evolution of surfing and the development of the surfboard. As you enter the main foyer of the restaurant each element has been specifically designed to create a mood of an older time, but in a contemporary setting. Duke’s La Jolla specializes in local sustainable fish caught daily in our local waters along with premium steaks, all natural pork, free range chicken and locally sourced produce from local farms. Every event at Duke’s is served with the warm, personalized service that is the signature of Duke’s. So whether it is a large scale brunch gathering overlooking the sparkling waters or an intimate evening reception with the backdrop of the southern California coast; Duke’s La Jolla has the perfect venue for your celebration. 2 BAREFOOT BAR LAYOUT A panoramic oceanfront setting for your event at Duke’s. This dining area on our upper level is highlighted by sweeping views of the Pacific and offers a dedicated bar opening to an ocean-view patio. The Barefoot Bar seats 30 to 120 guests and hosts up to 150 guests standing. -

La Plaza La Jolla La Plaza La Jolla 7863 - 7877 Girard Avenue La Jolla, Ca 92037

LA PLAZA LA JOLLA LA PLAZA LA JOLLA 7863 - 7877 GIRARD AVENUE LA JOLLA, CA 92037 • ±27,000 SF shopping center in the affluent La Jolla community AVAILABLE FOR LEASE • Situated in La Jolla’s prestigious shopping and dining hub with close proximity to some of San 101/202 107 114 Diego’s top tourist destinations 2-level corner retail / In-line retail space adjacent to Retail opportunity with direct • Located on the dynamic intersection of Girard Avenue and Wall Street restaurant opportunity the open-air courtyard access to Girard Ave. and the open-air courtyard • Recently renovated plaza with an open-air courtyard in the center ±3,632 SF ±799 SF ±1,472 SF Premier La Jolla Location Situated in the heart of the Village of La Jolla on the highly coveted Girard Avenue and surrounded by distinctive dining, luxury shopping and world class hotels and homes. La Plaza | La Jolla offers ideal frontage and visibility in the center of “The Jewel” and is positioned to capture the strong local demographics while also drawing from La Jolla’s thriving tourism industry. VE CO LLA LA JO Ellen Browning Scripps Park W A L L P S R TR O E E S E U T N P E E V C A D T R A S R T I R G E E T SUSHI ON THE ROCK BLUSH TAN THE HYDRATION LA PLAZA ROOM TENANTS CATANIA COASTAL ITALIAN BRILLIANT EARTH BROWBOSS BROW & BEAUTY ELIXIR ESPRESSO & WINE-BAR TEUSCHER CHOCOLATES JOIN THIS ONE | 10 SALON LINE UP OF BEAMING EXQUISITE TWO WELLNESS CO-TENANTS COMPASS NEIGHBORS La Plaza is Located on one of the most premier corners of La Jolla, providing unparalleled visibility and a unique -

Section 3.7 Marine Mammals

Point Mugu Sea Range Draft EIS/OEIS April 2020 Environmental Impact Statement/ Overseas Environmental Impact Statement Point Mugu Sea Range TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.7 Marine Mammals ............................................................................................................. 3.7-1 3.7.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 3.7-1 3.7.2 Region of Influence ............................................................................................... 3.7-1 3.7.3 Approach to Analysis ............................................................................................ 3.7-1 3.7.4 Affected Environment ........................................................................................... 3.7-2 3.7.4.1 General Background .............................................................................. 3.7-2 3.7.4.2 Mysticete Cetaceans Expected in the Study Area ............................... 3.7-28 3.7.4.3 Odontocete Cetaceans Expected in the Study Area ............................ 3.7-50 3.7.4.4 Otariid Pinnipeds Expected in the Study Area ..................................... 3.7-79 3.7.4.5 Phocid Pinnipeds Expected in the Study Area ..................................... 3.7-85 3.7.4.6 Mustelids (Sea Otter) Expected in the Study Area .............................. 3.7-89 3.7.5 Environmental Consequences ............................................................................ 3.7-91 3.7.5.1 Long-Term Consequences .................................................................. -

Interventions: Coastal Strategies to Resist, Retreat, and Adapt

Interventions: Coastal Strategies to Resist, Retreat, and Adapt A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in the school of Architecture & Interior Design in the College of Design, Architecture, Art, & Planning by Hannan Al-Timimi, B.A. in Urban Studies and Planning University of California San Diego Committee Chair: Edward Mitchell, MArch Committee Member: Vincent Sansalone, MArch Abstract: Rising sea levels caused by the warming of ocean waters, and freshwater from melting ice sheets threaten the California coast. If the global warming trend continues, about two-thirds of Southern California beaches would disappear.1 There are three possible solutions for endangered communities – retreat, resist, or adapt. This project will examine a combination of techniques that exist and are nonexistent on Beach-Barber Tract, one of La Jolla’s sixteen neighborhoods but could be implemented into Fiesta Island’s, Mission Bay Park. The proposition is that a combination of existing building solutions might be adapted. Those include walled courtyards varying from residential to civic scale, buildings raised on stilts or piloti, landscape- based solutions and hybrids between built form and landscape, including mat buildings. The mat building might be thought of as a constructed sponge, able to absorb storm surge and both accommodate existing use patterns and offer alternative use of urban space. Case studies of architectural and landscape techniques will support the design thesis and a range of types and urban organizations will be roughly calibrated to anticipate future storms. The proposal will provide both a theoretical and practical set of projections to redesign a more resilient coastal community. -

San Diego Natural History Museum Whalers Museum Whalers Handbook Jmorris

San Diego Natural History Museum Whalers Museum Whalers Handbook jmorris Revised 2016 by Uli Burgin This page intentionally blank SECTION 1: VOLUNTEER BASICS 1 SECTION 2: MARINE MAMMALS AND THEIR ADAPTATIONS 5 SECTION 3: INTRODUCTION TO CETACEANS 10 INTRODUCTION TO THE GRAY WHALE 15 SECTION 5: RORQUALS 23 SECTION 6: ODONTOCETES (TOOTHED WHALES) 31 SECTION 7: PINNIPEDS—SEA LIONS AND SEALS 41 SECTION 8: OTHER MARINE LIFE YOU MAY SEE 45 SECTION 9: BIRDING ON THE HORNBLOWER 49 SECTION 10: SAN DIEGO BAY 55 SECTION 11: DOING THE PRESENTATION 63 SECTION 12: FACTS YOU SHOULD KNOW 69 SECTION 13: VOLGISTICS AND SIGHTINGS LOG 75 SECTION 14: ON BOARD THE HORNBLOWER, CRUISE INFO AND MORE 79 SECTION 15: REFERENCES 83 This page intentionally blank Section 1: Volunteer Basics Welcome! We are pleased to have you as a volunteer Museum Whaler for the San Diego Natural History Museum. As a Museum Whaler you are carrying on a long tradition of whale watching here in southern California. Our first trips were offered to the public in 1957. These trips were led by pioneer whale watching naturalist Ray Gilmore, an employee of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and a research associate of the San Diego Natural History Museum. Ray’s whale-watching trips became well known over the years and integrated science and education with a lot of fun. We are sure that Ray would be very pleased with the San Diego Natural History Museum’s continued involvement in offering fun and educational whale watching experiences to the public through our connection with Hornblower Cruises and Events. -

Alex Kutaysov Buck 65 Martin Paradisis Steve Friedman Jamie

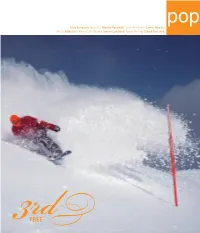

Alex Kutaysov Buck 65 Martin Paradisis Steve Friedman Jamie Hawley Blotto Mike Dee King of the Groms Simon Lyddiard Adam Melling David Benedek POP Burton 6.6.indd 1-2 30/6/06 2:40:55 PM Features 30 Dean ‘Blotto’ Gray On the recent Un..Inc tour down the east coast of Australia I was fortunate enough to spend a few weeks with Dean “Blotto” Gray. Blotto is no doubt one of the snowboard worlds most well known and respected photographers. When POP hit up Blotto for a portfolio, needless to say he was more than happy to help out... 42 Alex Kutaysov & 48 Mike Dee Alex Kutaysov is from the easternmost part of Russia known as the Kamchatka Peninsula. Kamchatka lies on the southern tip of Siberia, above Japan. If that’s not an interesting story then I don’t know what is. Similarly, Mike Doleman (aka Mike Dee) has just as a unique background. He is a third generation Australian merchant seafarer. So it’s surprising that they’re both incredibly talented snowboarders. 52 Simon Lyddiard & 54 Jamie Hawley Simon Lyddiard says that outside of skating, he’s a pretty boring guy. Sure, he likes to box, but that’s about it. Well that’s all well and good if you ignore the fact that’s he’s an amazing skateboarder. If he’s boring then I must be a billion playboy because we’re living in opposite land. And if you’re looking for someone to protect that opposite land then don’t count on Jamie Hawley. -

Peace, Love, Surf: Growing up in the 60’S (California Style)

Peace, Love, Surf: Growing Up In The 60’s (California Style) Peace, Love, Surf: Growing Up In The Sixties (California Style) Last update: February 18, 2017 Prologue It is my totally unbiased opinion that I grew up in what must be considered one of the most controversial and exciting times in the twentieth century, especially that narrow band of time during the sixties to mid-seventies. There were a lot of things going on like the Watts riots, the Cold War, the so called lunar landings, The Assassinations JFK, RFK, Martin , the Viet Nam war, People’s Park in Berkeley, the Monterey Pop Festival, the Kent State killings, Chicago Democratic Convention, Woodstock, SLA, Watergate, The Beach Boys, the Beatles, The Doors, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, the best music ever to be recorded, and, subsequently, the loss of J cubed (Jimi, Jim and Janis), late night sitcoms with Johnny, SLN, high school, college, presidential resignations and pardons, and more. It was like a pre-cyberspace overload era. Hence, given all that I went through during this short time on planet Earth, I felt the title of these short stories covers the appropriate time spectrum. There was a saying for the Viet Nam war that went around in this era called, “Peace, Love, Dove”. I took it and made a Page 1 of 34 Peace, Love, Surf: Growing Up In The 60’s (California Style) slight modification to reflect what it was like to grow up when surfing was taking off as a California craze; pray for Peace, free Love, let’s Surf. -

Jay Adams, the Essential V12.Pdf

THIS PHOTO WAS SHOT OF JAY IN 2013 BY HANS MOLENKAMP DURING ONE OF MANY PHOTO SESSIONS THAT HANS HAD AN OPPORTUNTY BY DAVID HACKETT 2002 TO SHOOT WITH THE JAY ADAMS’ CONTRIBUTION TO SKATEBOARDING DEFIES DESCRIPTION OR CATEGORY. JAY LEGENDARY AND ORIGINAL ADAMS IS CLEARLY THE ARCHETYPE OF MODERN-DAY SKATEBOARDING. HE’S THE REAL SEED OF SURF/SKATE STYLE. DEAL, THE ORIGINAL SEED, AND THE VIRUS THAT INFECTED ALL OF US. HE IS BEYOND COMPARISON. TO THIS DAY HE IS MORE VITAL, MORE DYNAMIC, MORE EXCITING, MORE UNPREDICTABLE, AND MORE SPONTANEOUS IN HIS APPROACH THAN ANY OTHER SKATER DEAD OR ALIVE. HE NEVER SKATES THE SAME RUN THE SAME WAY TWICE. HIS DEAL IS WICKEDLY RANDOM, YET TIGHT AND BEAUTIFUL TO WATCH- HE EVEN INVENTS NEW TRICKS DURING HIS RUNS. HE DESTROYS ALL CONVENTION AND ALL EXPECTATIONS. WATCHING HIM SKATE IS SOMETHING NEW EVERY SECOND: HE IS “SKATE AND DESTROY” PERSONIFIED. I THINK THE WORD “RADICAL” WAS FIRST USED IN SKATEBOARDING TO DESCRIBE JAY. ADAMS’ SKATEBOARDING IS AGGRESSION, STYLE, POWER AND FURY. WILD ABANDON, AND DESTRUCTION OF ALL FEAR, UNTAMED INDIVIDUALISM, AND A FREE-SPIRITED IN 2001, I SAW A PREVIEW COPY OF THE DOGTOWN DOCUMENTARY AND REALIZED THAT I HAD MADE A HUGE DETERMINATION TO RIP, TEAR AND SHRED - FOREVER A 100% SKATER FOR LIFE. OMISSION IN MY SKATEBOARD CAREER BY NOT KNOWING JAY ADAMS OR EVEN THAT MUCH ABOUT HIM. I RAN INTO DAVID HACKETT AT A LA COSTA EVENT AND IT TURNED OUT WE HAD A LOT IN COMMON, BESIDES THOSE ARE SOME PRETTY BIG STATEMENTS MADE ABOUT A GUY WHO ALMOST 30 YEARS JUST SKATEBOARDING.