Adrian Gonzalez Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

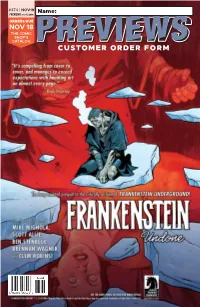

Customer Order Form

#374 | NOV19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:23:57 PM Nov19 CBLDF Ad.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:36:53 PM PROTECTOR #1 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS SPIDER-MAN #1 IDW PUBLISHING WONDER WOMAN #750 SEX CRIMINALS #26 DC COMICS IMAGE COMICS IRON MAN 2020 #1 MARVEL COMICS BATMAN #86 DC COMICS STRANGER THINGS: INTO THE FIRE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS RED SONJA: AGE OF CHAOS! #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SONIC THE HEDGEHOG #25 IDW PUBLISHING FRANKENSTEIN HEAVY VINYL: UNDONE #1 Y2K-O! OGN SC DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS NOv19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 4:18:59 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS • GRAPHIC NOVELS KIDZ #1 l ABLAZE Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower HC l ABRAMS COMICARTS Cat Shit One #1 l ANTARCTIC PRESS 1 Owly Volume 1: The Way Home GN (Color Edition) l GRAPHIX Catherine’s War GN l HARPER ALLEY BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams HC l INSIGHT COMICS The Plain Janes GN SC/HC l LITTLE BROWN FOR YOUNG READERS Nils: The Tree of Life HC l MAGNETIC PRESS 1 The Sunken Tower HC l ONI PRESS The Runaway Princess GN SC/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC White Ash #1 l SCOUT COMICS Doctor Who: The 13th Doctor Season 2 #1 l TITAN COMICS Tank Girl Color Classics ’93-’94 #3.1 l TITAN COMICS Quantum & Woody #1 (2020) l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Vagrant Queen: A Planet Called Doom #1 l VAULT COMICS BOOKS • MAGAZINES Austin Briggs: The Consummate Illustrator HC l AUAD PUBLISHING The Black Widow Little Golden Book HC l GOLDEN BOOKS -

2012 Morpheus Staff

2012 Morpheus Staff Editor-in-Chief Laura Van Valkenburgh Contest Director Lexie Pinkelman Layout & Design Director Brittany Cook Marketing Director Brittany Cook Cover Design Lemming Productions Merry the Wonder Cat appears courtesy of Sandy’s House-o-Cats. No animals were injured in the creation of this publication. Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 2 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 3 Table of Contents Morpheus Literary Competition Author Biographies...................5 3rd Place Winners.....................10 2nd Place Winners....................26 1st place Winners.....................43 Senior Writing Projects Author Biographies...................68 Brittany Cook...........................70 Lexie Pinkelman.......................109 Laura Van Valkenburgh...........140 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 4 Author Biographies Logan Burd Logan Burd is a junior English major from Tiffin, Ohio just trying to take advantage of any writing opportunity Heidelberg will allow. For “Onan on Hearing of his Broth- er’s Smiting,” Logan would like to thank Dr. Bill Reyer for helping in the revision process and Onan for making such a fas- cinating biblical tale. Erin Crenshaw Erin Crenshaw is a senior at Heidelberg. She is an English literature major. She writes. She dances. She prances. She leaps. She weeps. She sighs. She someday dies. Enjoy the Morpheus! Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 5 April Davidson April Davidson is a senior German major and English Writing minor from Cincin- nati, Ohio. She is the president of both the German Club and Brown/France Hall Council. She is also a member of Berg Events Council. After April graduates, she will be entering into a Masters program for German Studies. -

UN CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION CIVIL SOCIETY REVIEW: PERU 2011 Context and Purpose

UN CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION CIVIL SOCIETY REVIEW: PERU 2011 Context and purpose The UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) was adopted in 2003 and entered into force in December 2005. It is the first legally binding anti-corruption agreement applicable on a global basis. To date, 154 states have become parties to the convention. States have committed to implement a wide and detailed range of anti-corruption measures that affect their laws, institutions and practices. These measures promote prevention, criminalisation and law enforcement, international cooperation, asset recovery, technical assistance and information exchange. Concurrent with UNCAC’s entry into force in 2005, a Conference of the States Parties to the Convention (CoSP) was established to review and facilitate required activities. In November 2009 the CoSP agreed on a review mechanism that was to be “transparent, efficient, non-intrusive, inclusive and impartial”. It also agreed to two five-year review cycles, with the first on chapters III (Criminalisation and Law Enforcement) and IV (International Co-operation), and the second cycle on chapters II (Preventive Measures) and V (Asset Recovery). The mechanism included an Implementation Review Group (IRG), which met for the first time in June–July 2010 in Vienna and selected the order of countries to be reviewed in the first five-year cycle, including the 26 countries (originally 30) in the first year of review. UNCAC Article 13 requires States Parties to take appropriate measures including “to promote the active participation -

The Corrientes River Case: Indigenous People's

THE CORRIENTES RIVER CASE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLE'S MOBILIZATION IN RESPONSE TO OIL DEVELOPMENT IN THE PERUVIAN AMAZON by GRACIELA MARIA MERCEDES LU A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2009 ---------------- ii "The Corrientes River Case: Indigenous People's Mobilization in Response to Oil Development in the Peruvian Amazon," a thesis prepared by Graciela Marfa Mercedes Lu in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of International Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: lT.. hiS man.u...s. c. ript .has been approved by the advisor and committee named~ _be'oV\l __~!1_d _~Y--'3:~c~_ard Linton, Dean of the Graduate Scho~I_.. ~ Date Committee in Charge: Derrick Hindery, Chair Anita M. Weiss Carlos Aguirre Accepted by: III © 2009 Graciela Marfa Mercedes Lu IV An Abstract of the Thesis of Graciela M. Lu for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken December 2009 Title: THE CORRIENTES RIVER CASE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLE'S MOBILIZATION IN RESPONSE TO OIL DEVELOPMENT IN THE PERUVIAN AMAZON Approved: Derrick Hindery Economic models applied in Latin America tend to prioritize economic growth heavily based on extractive industries and a power distribution model that affects social equity and respect for human rights. This thesis advances our understanding of the social, political and environmental concerns that influenced the formation of a movement among the Achuar people, in response to oil exploitation activities in the Peruvian Amazon. -

State of the World's Indigenous Peoples

5th Volume State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples Photo: Fabian Amaru Muenala Fabian Photo: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources Acknowledgements The preparation of the State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources has been a collaborative effort. The Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues within the Division for Inclusive Social Development of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat oversaw the preparation of the publication. The thematic chapters were written by Mattias Åhrén, Cathal Doyle, Jérémie Gilbert, Naomi Lanoi Leleto, and Prabindra Shakya. Special acknowledge- ment also goes to the editor, Terri Lore, as well as the United Nations Graphic Design Unit of the Department of Global Communications. ST/ESA/375 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Inclusive Social Development Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 5TH Volume Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources United Nations New York, 2021 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. -

Years in the Abanico Del Pastaza - Why We Are Here Stop Theto Degradation of the Planet’S Natural Environment and to Build a Nature

LESSONS LEARNED years10 in + the Abanico del Pastaza Nature, cultures and challenges in the Northern Peruvian Amazon In the Abanico del Pastaza, the largest wetland complex in the Peruvian Amazon, some of the most successful and encouraging conservation stories were written. But, at the same time, these were also some of the toughest and most complex in terms of efforts and sacrifices by its people, in order to restore and safeguard the vital link between the health of the surrounding nature and their own. This short review of stories and lessons, which aims to share the example of the Achuar, Quechua, Kandozi and their kindred peoples with the rest of the world, is dedicated to them. When, in the late nineties, the PREFACE WWF team ventured into the © DIEGO PÉREZ / WWF vast complex of wetlands surrounding the Pastaza river, they did not realize that what they thought to be a “traditional” two-year project would become one of their longest interventions, including major challenges and innovations, both in Peru and in the Amazon basin. The small team, mainly made up of biologists and field technicians, aspired to technically support the creation of a natural protected area to guarantee the conservation of the high local natural diversity, which is also the basis to one of the highest rates of fishing productivity in the Amazon. Soon it became clear that this would not be a routine experience but, on the contrary, it would mark a sort of revolution in the way WWF Patricia León Melgar had addressed conservation in the Amazon until then. -

Infected Areas As on 2 December 1982 - Zones Infectées Au 2 Décembre 1982 for Enterra Used M Compiling Dus List, See No

WkiyEpidem Rec No. 48-3 December 1982 379 - Relevé èpidém hebd. N° 48 - 3 décembre 1982 INFLUENZA SURVEILLANCE SURVEILLANCE DE LA GRIPPE New Z e a l a n d (24 November 1982). —1 Three strains of influenza N o u v e l l e -Z é l a n d e (24 novembre 1982). —1 Trois souches du A(H1N1) virus were isolated during localized outbreaKs on the East virus grippal A(H 1N1) ont été isolées au cours de poussées localisées Coast of North Island. The strains were preliminarily characterized as sur la côte est de North Island. Elles ont été initialement identifiées A/England/333/80-like. Some influenza activity was also detected in comme étant analogues à A/England/333/80. On a également noté the Wellington area and two strains of influenza B/Singapore/222/79- une certaine activité grippale dans la région de Wellington et deux like virus were isolated. souches analogues au virus grippal B/Singapore/222/79 ont été iso lées. 1 See No 43, p. 335. 1 Voir N° 43, p. 335. Infected Areas as on 2 December 1982 - Zones infectées au 2 décembre 1982 For enterra used m compiling dus list, see No. 38, page 296 - Les critères appliques pour la compilation de cette liste sont publiés dans le N° 38, page 296. X Newly reported areas - Nouvelles zones signalées. PLAGUE - PESTE NIGERIA - NIGERIA Maharashtra State MaluKu Tenggara Regency Africa — Afrique Anambra State Ahmednagar Distnct MaluKu Utara Regency (excL port) Akola Distnct Nusatenggara Barat Province MADAGASCAR IKwo Local Goverment Area Borno State Amravati Distnct Lombok Barat Regency Antananarivo Province Kano Slate Aurangabad Distnct Lombok Tengah Regency A mananari vo- ViUt Lagos State Bhir Distnct Lombok Timur Regency 1er Arrondissement Niger State Buldhana Distnct Nusatenggara Timur TANZANIA, UNITED REP. -

Staff Cuts Reduce Programs; Student Participation Limited by PETER HOWARD Department

I Staff cuts reduce programs; student participation limited By PETER HOWARD department. jump of 67 per cent. said that as a matter of educational Faculty cut backs in several The Journalism Department. which In the same period, Dr. Brown philosophy priority is given to liberal departments within San lose State is in the same school, faces a similar noted, the number of faculty has arts areas. University next year will mean challenge. risen only 18 per cent from 11.5 to Dr. Moore said, however, that elimination of programs and im- Because its faculty is actually 13.6. while he "realizes Dr. Burns is in a position of quotas on the number of being reduced for next year from 13.8 This has meant the elimination of spot" because of what the chancellor students who may enter them. to 13.4 positions it may be forced to the magazine sequence, the cut gave him to work with, that Dr. The problem stems from two cut two classes in the basic planned for next year in the Spartan Burns' philosophy, when put into sourcesthe number of faculty journalism sequence. Daily staff, and a sharp increase in practice, is having very severe conse- positions SJSU was allocated by the As a result the chairman may have the size of the newswriting and quences for the school. chancellor's office and the division of to limit 10 40 the number of students editing classes. Students must pay these positions among the permitted to enroll on the Daily In fact, Dr. Brown sent a memo He also thinks Dr. -

Peru's 2000 Presidential Election

FPP-00-5 Peru’s 2000 Presidential Election: Undermining Confidence in Democracy? EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On April 9, 2000, Peruvian voters will cast their ballots in presidential and congressional elections. Nine political groups have registered, and four candidates are generally regarded as front-runners. Incumbent president Alberto Fujimori is seeking a controversial second re-election. His strongest opponent is Alejandro Toledo, a second-time candidate for Possible Peru (Perú Posible) followed by Alberto Andrade, the mayor of the capital city of Lima and leader of We are Peru (Somos Perú), and Luis Castañeda Lossio, the leader of the National Solidarity Party (Partido Solidaridad Nacional). Although much is at stake in these elections, differences in political programs have taken second place to the clash of individual personalities. From the outset, serious allegations have been made with regard to the rules of the electoral process and the unfair advantages of incumbency. Non-partisan election organizations, such as Transparencia, Foro Democratico and La Defensoría del Pueblo (the Ombudsman’s Office), along with international election observation missions, will play a crucial role in ensuring a clean process and educating the electorate about voting procedures. President Fujimori may represent a disturbing new trend – a movement away from democratic consolidation and toward the dismantling of the institutional underpinnings of representative democracy. RÉSUMÉ Le 9 avril 2000, les Péruviens devront se présenter aux urnes afin d’y élire les membres du Congrès ainsi que le président. Au total, neuf groupes politiques sont enregistrés et on peut discerner quatre candidats de premier plan. L’actuel président Alberto Fujimori alimente la controverse en tentant de se faire réélire pour une deuxième fois. -

This Is a Pre-Copy-Editing, Author-Produced PDF of an Article Accepted Following Peer Review for Publication in Geoforum

This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted following peer review for publication in Geoforum Making “a racket” but does anybody care? A study into environmental justice access and recognition through the political ecology of voice Adrian Gonzalez, Cardiff University. There is now growing support for the United Nations to explicitly recognise the human right to a healthy environment, and to strengthen the fight for environmental justice. One key consideration is to explore how accessible environmental justice is for citizens in low- and middle-income countries, who are adversely affected by pollution problems. This article will evaluate citizen access to environmental justice through the state via a case-study of Peru. To do so, the article utilises the political ecology of voice (PEV) theoretical framework. PEV can be defined as the study of several economic, political, social, and geographical factors over a specific temporal period, and their impact upon the use of voice by different stakeholders. The research was centred on two communities affected by oil pollution events within Peru’s Loreto Region. It will show that Loreto’s rural population are subjected to “shadow environmental citizenship”, in which they have only peripheral access to environmental justice through the state, which also does not adequately recognise or support their right to seek redress. This in turn, forces people to seek access and recognition of environmental justice through more unorthodox or radical forms of action, or via the support of non-state actors. Key Words: environmental justice; oil pollution; Peru; political ecology of voice; shadow environmental citizenship; political ecology 1. -

Graphic Novels & Trade Paperbacks

AUGUST 2008 GRAPHIC NOVELS & TRADE PAPERBACKS ITEM CODE TITLE PRICE AUG053316 1 WORLD MANGA VOL 1 TP £2.99 AUG053317 1 WORLD MANGA VOL 2 TP £2.99 SEP068078 100 BULLETS TP VOL 01 FIRST SHOT LAST CALL £6.50 FEB078229 100 BULLETS TP VOL 02 SPLIT SECOND CHANCE £9.99 MAR058150 100 BULLETS TP VOL 03 HANG UP ON THE HANG LOW £6.50 MAY058170 100 BULLETS TP VOL 04 FOREGONE TOMORROW £11.99 APR058054 100 BULLETS TP VOL 05 THE COUNTERFIFTH DETECTIVE (MR) £8.50 APR068251 100 BULLETS TP VOL 06 SIX FEET UNDER THE GUN £9.99 DEC048354 100 BULLETS TP VOL 07 SAMURAI £8.50 MAY050289 100 BULLETS TP VOL 08 THE HARD WAY (MR) £9.99 JAN060374 100 BULLETS TP VOL 09 STRYCHNINE LIVES (MR) £9.99 SEP060306 100 BULLETS TP VOL 10 DECAYED (MR) £9.99 MAY070233 100 BULLETS TP VOL 11 ONCE UPON A CRIME (MR) £8.50 STAR10512 100 BULLETS VOL 1 FIRST SHOT LAST CALL TP £6.50 JAN040032 100 PAINTINGS HC £9.99 JAN050367 100 PERCENT TP (MR) £16.99 DEC040302 1000 FACES TP VOL 01 (MR) £9.99 MAR063447 110 PER CENT GN £8.50 AUG052969 11TH CAT GN VOL 01 £7.50 NOV052978 11TH CAT GN VOL 02 £7.50 MAY063195 11TH CAT GN VOL 03 (RES) £7.50 AUG063347 11TH CAT GN VOL 04 £7.50 DEC060018 13TH SON WORSE THING WAITING TP £8.50 STAR19938 21 DOWN TP £12.99 JUN073692 24 NIGHTFALL TP £12.99 MAY061717 24 SEVEN GN VOL 01 £16.99 JUN071889 24 SEVEN GN VOL 02 £12.99 JAN073629 28 DAYS LATER THE AFTERMATH GN £11.99 JUN053035 30 DAYS OF NIGHT BLOODSUCKERS TALES HC VOL 01 (MR) £32.99 DEC042684 30 DAYS OF NIGHT HC (MR) £23.50 SEP042761 30 DAYS OF NIGHT RETURN TO BARROW HC (MR) £26.99 FEB073552 30 DAYS OF NIGHT -

Ict-601102 Stp Tucan3g

ICT-601102 STP TUCAN3G Wireless technologies for isolated rural communities in developing countries based on cellular 3G femtocell deployments D61 Situation report of the deployment area, sensitization results and state of transport networks Contractual Date of Delivery to the CE: 1 Oct 2013 Actual Date of Delivery to the CEC: 8 Mar 2014 Author(s): Juan Paco, César Córdova, Leopoldo Liñán, River Quispe, Darwin Auccapuri (PUCP), Ernesto Sánchez (FITEL), Ignacio Prieto (EHAS) Participant(s): PUCP, EHAS, FITEL Workpackage: 6 Est. person months: 4.5 Security: Public Dissemination Level: PU Version: d Total number of pages: 77 Abstract: This document presents information and activities carried out to ensure the provision of the required conditions for a successful deployment of the proposed platform in WP6. These activities have been carried out in the areas of intervention that had been chosen in agreement with the deliverable D21. This document presents a summary of the legal framework and regulation norms applicable to the project, as well as a description of the current situation in the area of intervention. It also contains a detailed description of the sensitization activities in each area. The document also provides a detailed report of the state of the target networks defined by testing technical capabilities and through the input and feedback of the users. Keyword list: sensitization; transport network; situation report, Document Revision History DATE ISSUE AUTHOR SUMMARY OF MAIN CHANGES 20-08-2013 a Juan Paco The table of content and introductory contents. Ernesto Sanchez Legal and regulatory framework and 19-09-2013 b Cesar Cordova Sensitization activities Added local actors and proposal for networks 20-09-2013 c Ignacio Prieto reinforcement Darwin Review of chapters, conclusions and 20-12-2013 d Auccapuri sensitization information.