The Strumble Head Story – So Far

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

The-Pembrokeshire-Marine-Code.Pdf

1 Skomer Island 2 South Pembrokeshire (Area 1) 4 Ramsey Island 100m from island P MOD Danger Area Caution Stack Rocks sensitive area for cetaceans Caution Caution porpoise sensitive area sensitive area for cetaceans Harbour (N 51 deg 44.36’ W 5 deg 16.88’) 3 South Pembrokeshire (Area 2) You are welcome to land on Skomer in North Haven You are more likely to (on the right hand beach as you approach from encounter porpoise 1hr the sea) GR 735 095. Access up onto the Island is Access to either side of slack between 10am and 6pm every day except Mondays, Wick allowed Skomer Marine Nature Reserve water. Extra caution (bank holidays excluded). It’s free if you remain on during August only required in this the beach, £6 landing fee payable for access onto Broad Haven Beach area at these the Island. Please find a member of staff for an times introductory talk and stay on the paths to avoid the P puffin burrows. Skomer Warden: 07971 114302 Stackpole Head Church Rock 5 St Margarets & Caldey Island 6 The Smalls Access: Caldey is a private island owned by the Reformed Cistercian Community. Boat owners are reminded that landing on Caldey from craft Extreme caution other than those in the Caldey highly sensitive Pool is not permitted. Access may be granted on special porpoise area occasions by pre-arrangement. 100m from island T 01834 844453 minimum safe 8 Grassholm 11 Strumble Head navigable speed only, Access to Grassholm is on south going tide. restricted due to the island 7 Skokholm Island being the worlds third largest Caution gannet colony (RSPB). -

Pembrokeshire Coast Pathtrailbl

Pemb-5 Back Cover-Q8__- 8/2/17 4:46 PM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Pembrokeshire Coast Path Pembrokeshire Coast Path 5 EDN Pembrokeshire ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, Pembrokeshire shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ COASTCOAST PATHPATH THE SUNDAY TIMES 96 large-scale maps & guides to 47 towns and villages With accommodation, pubs and restaurants in detailed PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT guides to 47 towns and villages Manchester includingincluding Tenby, Pembroke, Birmingham AMROTHAMROTH TOTO CARDIGANCARDIGAN St David’s, Fishguard & Cardigan Cardigan Cardiff Amroth JIM MANTHORPE & o IncludesIncludes 9696 detaileddetailed walkingwalking maps:maps: thethe London PEMBROKESHIRE 100km100km largest-scalelargest-scale mapsmaps availableavailable – At just COAST PATH 5050 milesmiles DANIEL McCROHAN under 1:20,000 (8cm or 311//88 inchesinches toto 11 mile)mile) thesethese areare biggerbigger thanthan eveneven thethe mostmost detaileddetailed The Pembrokeshire Coast walking maps currently available in the shops. Path followsfollows aa NationalNational Trail for 186 miles (299km) o Unique mapping features – walking around the magnificent times,times, directions,directions, trickytricky junctions,junctions, placesplaces toto coastline of the Pembroke- stay, places to eat, points of interest. These shire Coast National Park are not general-purpose maps but fully inin south-westsouth-west Wales.Wales. edited maps drawn by walkers for walkers. Renowned for its unspoilt sandy beaches, secluded o ItinerariesItineraries forfor allall walkerswalkers – whether coves, tiny fishing villages hiking the entire route or sampling high- and off-shore islands rich lightslights onon day walks or short breaks inin birdbird andand marinemarine life,life, thisthis National Trail provides o Detailed public transport information some of the best coastal Buses, trains and taxis for all access points walking in Britain. -

Day Distance (Miles)

Total Day Leg CP Name OS Grid Ref Distance Distance Time In Time Out Description (miles) (miles) (miles) Camp overnight in car park near Amroth Castle or Friday Night SN 167 071 surrounding area nearby for an early start. Saturday CP00 Amroth SN 173 072 0.0 0.0 Start of PCP is just down the road (east) of Castle. CP01 Saundersfoot SN 136 049 3.1 3.1 3.1 Car park in harbour area (breakfast). CP02 Tenby South Beach SN 130 001 8.0 8.0 4.9 Large car park at South Beach. CP03 Manorbier SS 081 976 12.8 12.8 4.9 Parking area past YHA. CP04 Freshwater East SS 016 978 18.6 18.6 5.8 Car park. Path crosses nearby. CP05 St. Govan's Chapel SR 967 930 25.9 25.9 7.2 Car park. Path passes nearby. CP06 Castlemartin SR 916 983 32.1 32.1 6.2 Park near roundabout where route crosses road. CP07 West Angle Bay SM 854 032 39.6 39.6 7.6 Car park. Path passes nearby. CP08 Rhoscrowther SM 897 020 44.9 44.9 5.3 End of minor road east side of Angle Bay. CP09 Pwllcrochan Church SM 921 027 48.5 48.5 3.6 Parking space by Church. CP10 Pembroke Castle SM 982 016 53.9 53.9 5.4 Car parking by river bridge below Castle. Saturday Night SS 008 973 Camp at East Trewent Farm near Freshwater East. Sunday CP10 Pembroke Castle SM 982 016 53.9 0.0 Start at same point as Day 1 finish. -

Wales National Seascape Character Assessment 26

SCAs (Snowdonia & Anglesey Seascape SCAs (Pembrokeshire Seascape Character Character Assessment, Fiona Fyfe Assessment, PCNP, December 2013) Associates, August 2013) Wales National Seascape 1: Teifi Estuary Character Assessment 29 1. Conwy Estuary 2: Cardigan Island and Cemmaes Head 26 3: Pen y Afr to Pen y Bal 2. Conwy Bay 30 29 4: Newport Bay 3. TraethLafan 25 28 9 8 5: Dinas Island 4. Menai Strait 10 7 6: Fishguard Bay east Figure 2: Draft Marine Character 24 5. Penmon 28 7: Fishguard and Goodwick Harbours Areas showing Local SCAs 23 6 6. Red Wharf Bay to Moelfre 13 11 5 8: North open sea 27 2 31 9: Newport and Fishguard outer sand bar 7. Dulas Bay 14 3 22 10: Crincoed Point and Strumble Head 01: Severn Estuary and Cardiff Bay 8. Amlwch and Cemaes 15 11: Strumble Head to Penbwchdy 02: Nash Sands and Glamorgan 9. Cemlyn Bay 4 16 1 12: Strumble Head deep water Coastal Waters 32 17 10. Carmel Head to Penrhyn 20 13: Penbwchdy to Penllechwen 18 03: Swansea Bay and Porthcawl 11. Holyhead 14: Western sand and gravel bars 21 12. Inland Sea 15: St Davids Head 04: Helwick Channel and The Gower 16: Whitesands Bay 13. Holyhead Mountain 05: Carmarthen Bay and Estuaries 17: Ramsey Sound 14. Rhoscolyn 18: Ramsey Island coastal waters 06: Bristol Channel 15. Rhosneigr 19 20 19 19: Bishops and Clerks 21 07: South Pembrokeshire Coastal and 16. Malltraeth 20: St Brides Bay coastal waters north Inshore Waters 17. Caernarfon 21: St Brides Bay coastal waters east 17 08: South Pembrokeshire Open Waters 33 22: St Brides Bay coastal waters south - 18. -

Pembrokeshire County Council Cyngor Sir Penfro

Pembrokeshire County Council Cyngor Sir Penfro Freedom of Information Request: 10679 Directorate: Community Services – Infrastructure Response Date: 07/07/2020 Request: Request for information regarding – Private Roads and Highways I would like to submit a Freedom of Information request for you to provide me with a full list (in a machine-readable format, preferably Excel) of highways maintainable at public expense (including adopted roads) in Pembrokeshire. In addition, I would also like to request a complete list of private roads and highways within the Borough. Finally, if available, I would like a list of roads and property maintained by Network Rail within the Borough. Response: Please see the attached excel spreadsheet for list of highways. Section 21 - Accessible by other means In accordance with Section 21 of the Act we are not required to reproduce information that is ‘accessible by other means’, i.e. the information is already available to the public, even if there is a fee for obtaining that information. We have therefore provided a Weblink to the information requested. • https://www.pembrokeshire.gov.uk/highways-development/highway-records Once on the webpage click on ‘local highways search service’ The highway register is publicly available on OS based plans for viewing at the office or alternatively the Council does provide a service where this information can be collated once the property of interest has been identified. A straightforward highway limit search is £18 per property, which includes a plan or £6 for an email confirmation personal search, the highway register show roads under agreement or bond. With regards to the list of roads and properties maintained by Network Rail we can confirm that Pembrokeshire County Council does not hold this information. -

TENBY MANUAL2006.Pdf

SOUTH WEST DYFED FIELD EXCURSION. Friday 31st March – Friday 7th April, 2006 Name …………………………………… Caravan ………………………………… University of Southampton School of Ocean and Earth Science Introduction The field guide has been produced to provide background information. It should be taken into the field each day for reference. Safety: You must follow the safety code given to you at the beginning of the academic year, not only for your own safety but for that of others. The main hazards are slippery rocks on the foreshore (especially those covered in sea-weed). Behaviour: The good name of Southampton University is dependent on your good behaviour. Please keep the caravans clean, avoid causing damage, and do not make excessive noise after 11:00pm. If there is any serious incident involving our group we will all be asked to leave. Aims and objectives of the course: To develop powers of observation and methods of recording geological information including: describing (in words and sketches with appropriate measurements) and interpreting geological features) measuring and describing sedimentary successions making a sketch section of the structure and stratigraphy of cliff exposures measuring the orientation and displacement of faults observing the textural and boundary relationships of igneous rocks noting the relationship between geological and geomorphological features plotting a simple geological map Most of these data should be recorded in your field notebook. Where necessary, special sheets will be supplied for logging or mapping. The following will be assessed (flexibility is required for adverse weather) 1. Sketch section of the cliffs at Broad Haven (Field Notebook) 2. A sedimentary log of part of the Marloes section (Log Sheets) 3. -

Coastal Cottages 2019 Collection

COASTAL COTTAGES 2019 COLLECTION PEMBROKESHIRE CEREDIGION CARMARTHENSHIRE Contents 2 Welcome 4 Places 6 Explore The Park 8 Beach Life 10 Child Friendly Holidays 12 Pet Friendly Holidays 14 Pembrokeshire In Four Seasons 16 Spring 18 Summer 20 Autumn 22 Winter 24 Go Wild In The West 26 Coastal Concierge 30 Waterwynch House 32 North Pembrokeshire 70 North West Pembrokeshire 108 West Pembrokeshire 160 South Pembrokeshire & Carmarthen 236 FAQ’s 238 Insurance & Booking Conditions 241 Here to Help Guide Welcome to the Coastal Cottages 2019 collection. As always, we have the very best properties of Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire and Ceredigion, all set in breathtaking locations along the coast, throughout the National Park and Welsh countryside. Providing memories #TheCoastalWay For almost 40 years we have been providing unique and traditional cottage holidays throughout West Wales for generations of guests. In this time we have grown but we still devote the same personal care, attention to detail and time to each of our guests as we did when we launched with just a hand full of properties back in 1982. What sets us apart from your everyday online only operator is our team and their personal knowledge. We all live right here in Pembrokeshire. We walk the beaches and hills, eat in the restaurants, enjoy the area with our children and pets and know the best places to explore whatever the weather. The Coastal Concierge team are always looking for the latest “Pembrokeshire thing” whether it’s local farmers launching a new dairy ice cream or the latest beachside pop up restaurant. Rest assured that if you stay with us, you will have an unrivalled experience from the moment you pick up the phone . -

Pembrokeshire: LANDMAP Change Detection: Visual & Sensory Aspect

Area 4: Pembrokeshire: LANDMAP Change Detection: Visual & Sensory Aspect Monitoring Report Final: March 2015 Bronwen Thomas Rev No.3 Date Pembrokeshire Contents 1.0. Introduction 2.0. Methodology Stage 1: Baseline of Change Stage 1a: Local Authority questionnaire findings Stage 1b: Additional desk-based information Stage 2: Fieldwork verification and survey completion 3.0. Monitoring Table Notes 4.0 General Approach to Recommended Amendments Relating to All-Wales Landscape Change Forestry conversion to broadleaf woodland Phytophthera felling Windfarms Single wind turbines Solar farms Settlement expansion Coastal erosion 5.0 Summary of Key Changes and Influences in Ceredigion Expansion of settlements New road schemes Holiday accommodation Airports and military Windfarms Forestry Moorland Large local developments Coast 6.0 Monitoring Table and Figures Bronwen Thomas Landscape Architect 05/05/2015 Page 2 of 35 www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Pembrokeshire 1.0 Introduction 1.1. In August 2013 Natural Resources Wales (NRW) commissioned Bronwen Thomas Landscape Architect (BTLA) to carry out stages 1, 2a and 2b of the interpretation of the LANDMAP Change Detection Packs (CDP) for the Visual & Sensory aspect covering several parts of Wales including Area 4 which includes Pembrokeshire (and Pembrokeshire Coast National Park). 1.2. In September 2013 BTLA was commissioned to prepare and manage the Local Authority questionnaire input into Visual & Sensory Change Detection across all of Wales. 1.3. In July 2014 BTLA was commissioned to carry out field visits, complete the surveys and update the Visual & Sensory data including the on-line surveys and GIS for the parts of Wales covered in the first stages, including Pembrokeshire. -

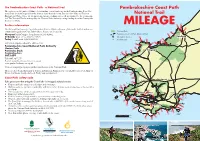

Coast Path Mileage Chart

The Pembrokeshire Coast Path - a National Trail Pembrokeshire Coast Path The path covers 186 miles (299km) of outstanding coastal landscape in the Pembrokeshire Coast Na - National Trail tional Park, from St Dogmaels in the north to Amroth in the south. It’s one of 16 National Trails in England and Wales. These are premier long-distance walking routes, all waymarked by the acorn sym - bol. The National Trail is managed by the National Park Authority, using funding from the Countryside Council for Wales. Further information MILEAGE The National Park operates three Information Centres which sell maps, guidebooks, leaflets and an ac - National Park commodation guide for Coast Path walkers. Centres are located at: Poppit Newport Pembrokeshire Coast Path (National Trail) i Bank Cottages, Long Street (01239) 820912 Information Centres CardiganCardigan St Davids i Tenby Oriel y Parc (01437) 720392 South Parade (01834) 845040 Youth Hostels Strumble Head All written enquiries should be addressed to: i Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority i Newport Llanion Park i Pembroke Dock FishguardFishguard Pembrokeshire Crymych Porthgain SA72 6DY Trevine Tel: 0845 345 7275 E-mail: [email protected] www.pembrokeshirecoast.org.uk StSt Davids i Solva Visit www.nt.pcnpa.org.uk for further information on the National Trail. Ramsey There are also Tourist Information Centres in Cardigan, Fishguard, Goodwick, Haverfordwest, Milford Island Newgale Sands Haven, Pembroke, Pembroke Dock, Tenby and Saundersfoot. Coast Path safety code i Haverfordwest Take great care when using the Coast Path - it is rugged, natural terrain. Broad Haven N N Keep to the Path, away from cliff edges and overhangs. -

De Coastal Way

De Coastal Way Een epische reis door Wales thewalesway.com visitsnowdonia.info visitpembrokeshire.com discoverceredigion.wales Waar is Wales? Ga De Wales Way Om er te komen. De Wales Way is een epische reis, drie verschillende routes –De North Wales Way, Wales is toegankelijk voor alle grote Britse steden, waaronder Londen, Birmingham, Manchester en De Coastal Way en De Cambrian Way - die u door kasteellanden, langs de kust en Liverpool. Wales heeft zijn eigen internationale luchthaven, Cardiff International Airport (CWL), die door ons bergachtige hart leiden. meer dan 50 directe routes heeft, waaronder grote Europese steden en meer dan 1.000 wereldwijde verbindingsbestemmingen. Wales is ook gemakkelijk bereikbaar vanaf de luchthavens Bristol (BRS), De Coastal Way loopt over de hele lengte van Cardigan Bay. Het is een 180 mijl (290 km) Birmingham (BHX), Manchester (MAN) en Liverpool (LPL). avontuurlijke reis die tussen blauwe zeeën aan de ene kant en bergen aan de andere kant leidt. 2 uur per trein van Londen We hebben de reis onderverdeeld in brokken terwijl het door de verschillende toeristische bestemming in Wales gaat - Snowdonia Mountains and Coast, Ceredigion en Pembrokeshire. 3 uur via de snelweg vanuit het En binnen elke bestemming bieden we gelegenheden om alles te bezoeken onder de titels Avontuur, centrum van Londen, 1 uur vanuit Liverpool, Manchester, Bristol Erfgoed, Landschap, Eten en Drinken, Wandelen en Golf. en Birmingham. Denk alsublieft niet dat deze 'Weg' in steen is gezet. Cardiff Airport heeft directe Het is ontworpen als een suggestie, niet een vluchten naar heel Europa en wereldwijde verbindingen via verplichting, met veel mogelijkheden om off-route cardiff-airport.com op Doha, te gaan en verder en dieper te verkennen. -

Number 14 March 2017 Price £4.50

Number 14 March 2017 Price £4.50 Welcome to the 14th edition of the Weslh Stone being done at Nolton Haven church and some of the Forum Newsletter. This is the largest we have techniques that are being used. We will then drive on produced to date and reflects the increasde activity to St David’s for lunch at c. 13.30. Cathedral and/ and willingness of members to write up their studies or Bishops palace will be visited in the afternoon to and observations. We have a full programm of field examine a range of English and Welsh stone used in meeting this year. the cathedral monuments and font. June 10th: St Maughans, Abbey Dore, Grosmont, Subscriptions Kilpeck If you have not paid your subscription for 2016 please Leader: John Davies forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew. Meet: 11.00am, abbey entrance Abbey Dore, [email protected]). (SO387304, post code HR2 0AA) The St Maughan’s Formation of Breconshire, PROGRAMME 2017 Herefordshire and Gwent includes sandstones which April 29th AGM & Annual Lecture can be carved with great detail. This gave rise to a The 2017 AGM, will be held at 11.00 am at St distinctive school of architecture in south-western Michael’s Centre, Llandaff, 54 Cardiff Road, Herefordshire based around the church of Kilpeck. Llandaff, CF5 2YJ, http://www.stmichaels.ac.uk/ Examination of buildings in the area has given a clue welcome. Coffee avaiable from 10.30am. to varieties of this formation otherwise difficult to detect due to the shortage of rock outcrops. We are delighted to welcome Isaak Hudson to give the 2017 annual lecture.