Reading the Heroic Slave As a Response to Uncle Tom's Cabin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2019 Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery Jake Spangler DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Spangler, Jake, "Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery" (2019). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June 2019 BY Jake C. Spangler Department of English College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois This project is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Jim Cowan Father, Friend, Teacher Table of Contents Dedication / i Table of Contents / ii Acknowledgements / iii Introduction / 1 I. “I Could Not Deem Myself a Slave” / 9 II. The Heroic Slave / 26 III. The “Files” of Frederick Douglass / 53 Bibliography / 76 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support of several scholars and readers. -

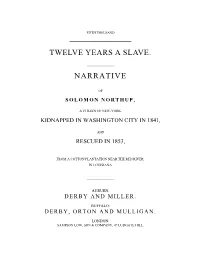

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2006 Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction Miya G. Abbot University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abbot, Miya G., "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1487 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. Abbot entitled "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of , with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary Jo Reiff, Janet Atwill Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. -

Text Complexity Analysis

Text Complexity Analysis Text complexity analysis Michelle Henry Teachfest Connecticut: Summer Academy Created by: Event/Date: July 29, 2014 Excerpt from Narrative Of The Life of Frederick Public Domain Text and Where to Access Douglass, An American Slave, written by Frederick http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/dougeduc.html Author Text Douglass Text Description Published in 1845, Narrative of The Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave was the first volume of Douglass’s autobiography. In this excerpt, Douglass revealed the mental oppression that he had experienced as a slave and the importance of literacy as a means to enlightenment and freedom. It could be inferred that illiteracy perpetuated a slave’s ignorance and compliance while literacy inspired critical thinking and self-empowerment. For instance, alluding to his reading of the “Columbia Orator”, Douglass demonstrates how he was able to see the evil of slavery and how this realization instilled a profound sense of discontentment. This excerpt would fit well in an American Literature or U.S. History unit, highlighting the slave narrative genre and the struggles of slaves during the antebellum period. Douglass employs pedantic and emotional diction to convey the injustice of slavery. Quantitative th Lexile and Grade Level 1070L- 11 Grade Text Length 483 words Qualitative Meaning/Central Ideas Text Structure/Organization Literature has an impacting influence on readers. During the slave era, This text is a well-known excerpt of Douglass’s autobiography. The organization is literacy was a means to freedom. In today’s society, literacy and education sequential with Douglass introducing his first exposure to reading and then are just as important. -

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the HBSC Collection

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center’s Collections Finding Aid To schedule a research appointment, please call the Collections Manager at 860.522.9258 ext. 313 or email [email protected] Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the Stowe Center's Collection Note: See end of document for manuscript type definitions. Manuscript type & Recipient Title Date Place length Collection Summary Other Information [Stowe's first known letter] Ten year-old Harriet Beecher writes to her older brother Edward attending Yale. She would like to see "my little sister Isabella". Foote family news. Talks of spending the Nutplains summer at Nutplains. Asks him to write back. Loose signatures of Beecher, Edward (1803-1895) 1822 March 14 [Guilford, CT] ALS, 1 pp. Acquisitions Lyman Beecher and HBS. Album which belonged to HBS; marbelized paper with red leather spine. First written page inscribed: Your Affectionate Father Lyman At end, 1 1/2-page mss of a 28 verse, seven Beecher Sufficient to the day is the evil thereof. Hartford Aug 24, stanza poem, composed by Mrs. Stowe, 1840". Pages 2 and 3 include a poem. There follow 65 mss entitled " Who shall not fear thee oh Lord". poems, original and quotes, and prose from relatives and friends, This poem seems never to have been Katharine S. including HBS's teacher at Miss Pierece's school in Litchfield, CT, published. [Pub. in The Hartford Courant Autograph Bound mss, 74 Day, Bound John Brace. Also two poems of Mrs. Hemans, copied in HBS's Sunday Magazine, Sept., 1960].Several album 1824-1844 Hartford, CT pp. -

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass:An American Slave by Frederick Douglas

Study Material On The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass:An American Slave By Frederick Douglas For the students of The Department of English, University of Calcutta MA Semester II DSE II Nineteenth Century American Literature Prepared by Dr. Sinjini Bandyopadhyay Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Calcutta I. Knowledge and Power: If the trajectory of Frederick Douglass’s life refers to a movement from oppression to liberty then it certainly involve a journey from ignorance to knowledge. Douglass’s freedom is amenable to the urge of knowing. With an innate ‘Humanist’ zeal Douglas is keen to know the ideas of the world; language, history, space, culture and so on and at the same time is eager to trace his identity. The issue of identity may be elaborated with reference to the following points: a) Confusion regarding his parental identity b) The rumour has it that his master is his father c) Vague memory of mother (Students may work upon the metaphor of the darkness of night as his mother was allowed to meet him only at night) d) Less attachment to his siblings who worked in the same plantation Such an absence of proper familial identity exasperated Douglass’s desire to establish an identity on his own which, he realized even at an early age, can be developed only with knowledge and learning. Douglass’ journey towards freedom is coterminous with knowledge the begins with a programme for literacy that he chose for himself, continued with, despite hurdles of several sorts coming along all the way and where he involves other fellow slaves. -

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

The End of Uncle Tom

1 THE END OF UNCLE TOM A woman, her body ripped vertically in half, introduces The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven from 1995 (figs.3 and 4), while a visual narra- tive with both life and death at stake undulates beyond the accusatory gesture of her pointed finger. An adult man raises his hands to the sky, begging for deliverance, and delivers a baby. A second man, obese and legless, stabs one child with his sword while joined at the pelvis with another. A trio of children play a dangerous game that involves a hatchet, a chopping block, a sharp stick, and a bucket. One child has left the group and is making her way, with rhythmic defecation, toward three adult women who are naked to the waist and nursing each other. A baby girl falls from the lap of one woman while reaching for her breast. With its references to scatology, infanticide, sodomy, pedophilia, and child neglect, this tableau is a troubling tribute to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—the sentimental, antislavery novel written in 1852. It is clearly not a straightfor- ward illustration, yet the title and explicit references to racialized and sexualized violence on an antebellum plantation leave little doubt that there is a significant relationship between the two works. Cut from black paper and adhered to white gallery walls, this scene is composed of figures set within a landscape and depicted in silhouette. The medium is particularly apt for this work, and for Walker’s project more broadly, for a number of reasons. -

Julia Faisst, Phin Beiheft

PhiN Beiheft | Supplement 5/2012: 71 Julia Faisst (Siegen) Degrees of Exposure: Frederick Douglass, Daguerreotypes, and Representations of Freedom1 This essay investigates the picture-making processes in the writings of Frederick Douglass, one of the most articulate critics of photography in the second half of the nineteenth century. Through his fiction, speeches on photography, three autobiographies, and frontispieces, he fashioned himself as the most "representative" African American of his time, and effectively updated and expanded the image of the increasingly emancipated African American self. Tracing Douglass's project of self-fashioning – both of himself and his race – with the aid of images as well as words is the major aim of this essay. Through a close reading of the historical novella "The Heroic Slave," I examine how the face of a slave imprints itself on the photographic memory of a white man as it would on a silvered daguerreotype plate – transforming the latter into a committed abolitionist. The essay furthermore uncovers how the transformation of the novella's slave into a free man is described in terms of various photographic genres: first a "type," Augustus Washington (whose life story mirrors that of Douglass) changes into a subject worthy of portraiture. As he explored photographic genres in his writings, Douglass launched the genre of African American fiction. Moreover, through his pronounced interest in mixed media, he functioned as an immediate precursor to modernist authors who produced literature on the basis of photographic imagery. Overall, this essay reveals how Douglass performed his own progress within his photographically inflected writings, and turned both himself and his characters into free people. -

Introduction

Introduction R. J. Ellis One of the most influential books ever written, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly was also one of the most popular in the nineteenth century. Stowe wrote her novel in order to advance the anti-slavery cause in the ante-bellum USA, and rooted her attempt to do this in a ‘moral suasionist’ approach — one designed to persuade her US American compatriots by appealing to their God-given sense of morality. This led to some criticism from immediate abolitionists — who wished to see slavery abolished immediately rather than rely upon [per]suasion. Uncle Tom's Cabin was first published in 1852 as a serial in the abolitionist newspaper National Era . It was then printed in two volumes in Boston by John P. Jewett and Company later in 1852 (with illustrations by Hammatt Billings). The first printing of five thousand copies was exhausted in a few days. Title page, with illustration by Hammatt Billings, Uncle Tom’s Cabin Vol. 1, Boston, John P. Jewett and Co., 1852 During 1852 several reissues were printed from the plates of the first edition; each reprinting also appearing in two volumes, with the addition of the words ‘Tenth’ to ‘One Hundred and Twentieth Thousand’ on the title page, to distinguish between each successive re-issue. Later reprintings of the two-volume original carried even higher numbers. These reprints appeared in various bindings — some editions being quite lavishly bound. One-volume versions also appeared that same year — most of these being pirated editions. From the start the book attracted enormous attention. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads.