The FCC's Restrictions on Employee's Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T

A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 By Peter T. Humphrey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor James Q. Davies, Chair Professor Nicholas de Monchaux Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Nicholas Mathew Spring 2021 Abstract A History of Electroacoustics: Hollywood 1956 – 1963 by Peter T. Humphrey Doctor of Philosophy in Music and the Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor James Q. Davies, Chair This dissertation argues that a cinematic approach to music recording developed during the 1950s, modeling the recording process of movie producers in post-production studios. This approach to recorded sound constructed an imaginary listener consisting of a blank perceptual space, whose sonic-auditory experience could be controlled through electroacoustic devices. This history provides an audiovisual genealogy for electroacoustic sound that challenges histories of recording that have privileged Thomas Edison’s 1877 phonograph and the recording industry it generated. It is elucidated through a consideration of the use of electroacoustic technologies for music that centered in Hollywood and drew upon sound recording practices from the movie industry. This consideration is undertaken through research in three technologies that underwent significant development in the 1950s: the recording studio, the mixing board, and the synthesizer. The 1956 Capitol Records Studio in Hollywood was the first purpose-built recording studio to be modelled on sound stages from the neighboring film lots. The mixing board was the paradigmatic tool of the recording studio, a central interface from which to direct and shape sound. -

UWM Libraries Digital Collections

Concert review: pg 13 David Byrne returns to Milwaukee uwMrOSl The Student-Run Independent Newspaper at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee The potential presidencies of V Obama and McCain compared Controversy over News pg 5 bookstore sweatshop allegations RunUp the Runway showcases local fashion designers Robert Spencer, founder of Jihad Watch, speaking Thursday evening in at MAM Bolton Hall. Post photo by Alana Soehartono Concert Reviews: Spencer lecture lacked Minus the Bear Mountain Goats outbursts, interruptions Man Man David Byrne Extensive Freedom Center is a conserva SDS claims stem from Bookstore, SDS approached the tive organization founded by UWM's refusal to join Brand Standards Committee security prevents Horowitz, who was the subject fringe pg 7 with a request that UWM reject of a controversial visit to UWM DSP program their support of two groups used Horowitz repeat this past spring. to assure all logo sale items are Prior to entering the lecture Women's soccer By Cordelia Ellis manufactured in a sweatshop By Jo Rey Lopez and Kevin Lessmiller hail, attendees had to endure an Special to The Post free environment with equal airport-like security screening, breaks season worker rights. With enough security to complete with a walk-through goal record The UW-Milwaukee Students SDS requested that UWM join quell a small riot, conservative metal detector, bag and purse for a Democratic Society (SDS) the Designated Supplier Program speaker Robert Spencer took the search, followed by another recently launched an anti-sweat (DSP), a proposed new system by stage in UW-Milwaukee's Bolton screening by a handheld metal "Kicks for Hoops" shop campaign, which claims WRC. -

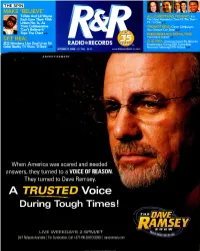

A TRUSTED Voice

THE SPIN MAKE 'BELIEVE' T Pain And LiI Wayne A MAS FORMAT: It's Each Earn Their Fifth The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year - Urban No. ls, As Til -'s Over Their Collaborative PROMOTIONS: Clever Campaigns 'Can't Believe It' You Station Can Steal Tops The Chart PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES: The Global Ir,pact GET ; THE PPM: Concerns Raised By Minority 302 Members Live Dual Lives On RADIO & RECORDS Broadcasters During R &R Conve -rtion Cable Reality TV Show 'Z Rock' Resonate Following PPM Rollout OCTOBER 17, 2008 NO. 1784 $6.EO www.RadioandRecc -c s.com ADVERTISEMENT When America was scared and needed nswers, they turned to a VOICE OF REASON. They turned to Dave Ramsey. A TRUSTED Voice During Tough Times! 7 /THEDAVÊ7 C AN'S HOW Ey LIVE WEEKDAYS 2-5PM/ET 0?e%% aáens caller aller cal\e 24/7 Re-eeds Ava lable For Syndication, Call 1- 877 -410 -DAVE (32g3) daveramsey.com www.americanradiohistory.com National media appearances When America was scared and needed focused on the economic crisis: answers, they turned to a voice Your World with Neil Cavuto (5x) of reason. They turned to Dave Ramsey. Fox Business' Happy Hour (3x) The O'Reilly Factor Fox Business with Dagen McDowell and Brian Sullivan Fox Business with Stuart Varney (5x) Fox Business' Bulls & Bears (2x) America's Nightly Scoreboard (2x) Larry King Live (3x) Fox & Friends (7x) Geraldo at Large (2x) Good Morning America (3x) Nightline The Early Show Huckabee The Morning Show with Mike and Juliet (3x) Money for Breakfast Glenn Beck Rick & Bubba (3x) The Phil Valentine Show and serving our local affiliates: WGST Atlanta - Randy Cook KTRH Houston - Michael Berry KEX Portland - The Morning Update with Paul Linnman WWTN Nashville - Ralph Bristol KTRH Houston - Morning News with Lana Hughes and J.P. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Extensions of Remarks Hon. Harold T. Johnson

January 6, 1969 '.EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 247 REPORT OF TELLERS of the United States, as delivered to the 2228, New Senate Office Building, before Mr. CURTIS. Mr. President, on behalf President of the Senate, is as follows: the Committee on the Judiciary, on John of the tellers on the part of the Senate, The whole number of electors ap N. Mitchell, of New York, Attorney Gen I wish to report on the counting of the pointed to vote for Vice President of the eral-designate. vote for President and Vice President. United States is 538, of which a majority At the indicated time and place per The state of the vote for President of is 270. sons interested in the hearing may make the United States, as delivered to the SPIRO T. AGNEW, of the State of Mary such representations as may be pertinent. President of the Senate, is as follows: land, has received for Vice President of The whole number of electors ap the United States 301 votes. EDMUND s. MUSKIE, of the State of ADJOURNMENT UNTIL THURSDAY, pointed to vote for President of the JANUARY 9, 1969 United States is 538, of which a majority Maine, has received 191 votes. Curtis E. LeMay, of the State of Cali Mr. KENNEDY. Mr. President, if there is 270. fornia, has received 46 votes. is no further business to come before the Richard M. Nixon, of the State of New Senate, I move, in accordance with the York, has received for President of the previous order, that the Senate stand in United States 301 votes. -

2008/08/02 Tears of Rain / Charlie Haden & Pat Metheny

2008/08/02 Tears of Rain / Charlie Haden & Pat Metheny Beyond The Missouri Sky Doina, Parov's Daichevo / Tony McManus unreleased track Hard Love / Martin Simpson Live Go To The Mardi Gras / Jon Cleary Live - Mo' Hippa Buzz Buzz Buzz / The Hollywood Flames The Doo Wop Box Harlem Shuffle / Bob & Earl Land of 1000 Dances Walking In Memphis / Marc Cohn Marc Cohn Let Me Be Your Witness / Marc Cohn Join The Parade Astral Weeks / Van Morrison Astral Weeks The Way Young Lovers Do / Van Morrison Astral Weeks Come Running / Van Morrison Moondance Crazy Love / Van Morrison Moondance Domino / Van Morrison His Band And The Street Choir If I Ever Needed Someone / Van Morrison His Band And The Street Choir Johnny Cash / Ry Cooder I, Flathead 5000 Country Music Songs / Ry Cooder I, Flathead Sliding Home / Cindy Cashdollar Slide Show 2008/08/09 I Wanna Dance With Somebody / David Byrne Live from Austin TX Them Changes / King Curtis Aretha Franklin & KIng Curtis Live at Fillmore West - Don't Fight The Feeling Com' By H'Yere-Good Lord / Nina Simone It Is Finished Funkier Than A Mosquito's Tweeter / Nina Simone It Is Finished I Smell Trouble / Ike & Tina Turner Soul To Soul In The Midnight Hour / Wilson Pickett A Man And A Half Bring It On Home To Me~Nothing Can Change This Love / Sam Cooke live at Harlem Square Club - 1963 Louisiana / John Boutte live at Jazz Fest 2007 Mother, Mother / Allen Toussaint live at Jazz Fest 2007 Engingilaye & Te Dikalo / Richard Bona Bona Makes You Sweat - Live That's What A Little Dream Can Do / Amos Garrett Off The Floor Live! Inori / Pat Metheny w. -

Resonating Frequencies of a Virtual Learning Community: an Ethnographic Case Study of Online Faculty Development at Columbia College Chicago David S

National Louis University Digital Commons@NLU Dissertations 3-2015 Resonating Frequencies of a Virtual Learning Community: An Ethnographic Case Study of Online Faculty Development at Columbia College Chicago David S. Noffs National Louis University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/diss Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons, Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Online and Distance Education Commons Recommended Citation Noffs, David S., "Resonating Frequencies of a Virtual Learning Community: An Ethnographic Case Study of Online Faculty Development at Columbia College Chicago" (2015). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/diss/144 This Dissertation - Public Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@NLU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@NLU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resonating Frequencies of a Virtual Learning Community: An Ethnographic Case Study of Online Faculty Development at Columbia College Chicago by David S. Noffs B.M., Roosevelt University, 1983 M.P.H., Benedictine University, 1999 A Critical Engagement Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Department of Adult and Continuing Education National-Louis University June, 2015 Acknowledgment I want to acknowledge the staff and faculty of Columbia College Chicago who have been both my greatest supporters and critics, always keeping me on task for the sake of our common goal; striving for excellence in education. In particular, I want to thank my friends and colleagues at the Center for Innovation in Teaching Excellence who have been my eyes, ears and heart in my search to make meaning of an emerging education ecology. -

Dry Martini Cocktail Ονομασία Των Κοκτέιλ Έχει Τροφοδοτήσει Πολλές Ιστορί- Πίνεται Από Όλο Τον Καλό Κόσμο, Συμβολίζει Το Κοσμοπολίτικο Lifestyle Και Ες

30 ΙΟΥΛΙΟΥ - 5 ΑΥΓΟΥΣΤΟΥ 2009 . ΤΕΥΧΟΣ 268 . 210 Η ΦΩΝΗ ΤΗΣ ΑΘΗΝΑΣ . WWW.ATHENSVOICE.GR . FREE PRESS KAΘΕ ΠΕΜΠΤΗ ATHENS voice καλό καλοκαίρι σελ. 25 Τελευταίες προτάσεις για ένα δροσερό Αύγουστο, Παραλιακή βόλτα στη Σαντορίνη Ο Σ. Βούγιας κι ο Σ. Κωνσταντινίδης προτείνουν, σελ. 18 Οι «Πέρσες» μπαίνουν στην Επίδαυρο Η A.V. στις πρόβες. Της Δήμητρας Τριανταφύλλου, σελ. 26 2 A.V. 30 ΙΟΥΛΙΟΥ - 5 ΑΥΓΟΥΣΤΟΥ 2009 Εικόνα εξωφύλλου: Περιεχόμενα 30/7 - 5/8/09 Χρήστος Κεχαγιόγλου Θέματα Στήλες 10 Ζωντανός στην Αθήνα: Της Μανίνας Ζουμπουλάκη 18 Παραλιακή βόλτα στη Σαντορίνη 12 Info-diet: Εβδομαδιαίο χρηματιστήριο Ο Σ. Βούγιας κι ο Σ. Κωνσταντινίδης αξιών από τη Σταυρούλα Παναγιωτάκη προτείνουν 13 Απαντήσεις του Forrest Gump: Του Nίκου Ζαχαριάδη 22 Το χαμόγελο του χοίρου 14 Shoot me: Του Κωνσταντίνου Ρήγου Του Νίκου Γεωργιάδη 16 Πανικοβάλ των 500: Του Γ. Νένε 36 Travel: Της Α. Καραγκούνη Κύρτσου 23 Για τα πανηγύρια 38 Sports: Του Μιχάλη Λεάνη Του Ευτύχη Παλλήκαρη 39 Sκ8: Του Billy Γρυπάρη 44 Taste: Της Νενέλας Γεωργελέ Καλό καλοκαίρι 25 ΚΑΛΟ ΚΑΛΟΚΑΙΡΙ 25 46 Στο πιάτο: Της Τζ. Σταυροπούλου Προτάσεις για να περάσεις καλά 51 G&L: Του Λύο Καλοβυρνά τον Αύγουστο Από το team της A.V. 52 Θέατρο: Της Αργυρώς Μποζώνη 53 Ταινίες: Του Γ. Κρασσακόπουλου 26 Οι «Πέρσες» μπαίνουν 57 Various artists: Του Μάκη Μηλάτου στην Επίδαυρο 41 Αθήνα 210 Οδηγός 59 BookVoice: Των Α. Μπιρμπίλη, Η A.V. στις πρόβες Γ. Δημητρακόπουλου της πολυαναμενόμενης παράστασης Επιλογές της εβδομάδας. Εστιατόρια, 56 Soul/Βody/Μind: Της Δήμητρας Τριανταφύλλου μπαρ, cafés, κλαμπ, επιλεκτικός οδηγός Της Ελίνας Αναγνωστοπούλου της A.V. -

Parenthetical Girls

SENTIREASCOLTAREDIGital MAGAZINE SETTEMBRE N. 47 DAVID EUGENE EDWARDS ALVA NOTO SOUL JAZZ RECORDS NEW YEAR ARMATRADING PARENTHETICAL GIRLS 4 NEWS 6 TURN ON SILVER RAY, NEW YEAR, ALVA NOTO 16 TUNE IN PARENTHETICAL GIRLS, DAVID EUGENE EDWARDS 24 DroP OUT SOUL JAZZ, NOISE ROCK ITALIANO 42 RECENSIONI ABE VIGODA, KEVIN DRUMM, DAVID BYRNE & BRIAN ENO 106 WE ARE DEMO 108 REARVIEW Mirror JOAN ARMATRADING 120 CUlt MOVIE REDACTED 122 LA SERA DELLA PRIMA IL CAVALIERE OSCURO, FUNNY GAMES 126 I COSIDDETTI CONTEMPORANEI HANNS EISLER DIRETTORE Edoardo Bridda COOR D IN A MENTO Teresa Greco CON S ULENTI A LL A RE da ZIONE Daniele Follero Stefano Solventi ST A FF Gaspare Caliri Nicolas Campagnari Antonello Comunale Antonio Puglia HA NNO C OLL A BOR A TO Gianni Avella, Paolo Bassotti, Davide Brace, Marco Braggion, Filippo Bordignon, Marco Canepari, Manfredi Lamartina, Gabriele Maruti, Stefano Pifferi, Andrea Provinciali, Costanza Salvi, Vincenzo Santarcangelo, Giancarlo Turra, Fabrizio Zampighi, Giuseppe Zucco GUI da S PIRITU A LE Adriano Trauber (1966-2004) GR A FI ca Nicolas Campagnari IN C OPERTIN A Parenthetical Girls SentireAscoltare online music magazine Registrazione Trib.BO N° 7590 del 28/10/05 Editore Edoardo Bridda Direttore responsabile Antonello Comunale Provider NGI S.p.A. Copyright © 2008 Edoardo Bridda. Tutti i diritti riservati.La riproduzione totale o parziale, in qualsiasi forma, su qualsiasi supporto e con qualsiasi mezzo, è proibita senza autorizzazione scritta di SentireAscoltare SA 3 S W Make Mine Music, così come il progetto so- accorge di aver messo su anche nella stes- Inoltre installazioni audio e video, proiezio- lista di Glen Johnson, Textile Ranch (The sa cartella la versione non masterizzata del ni, incontri con gli artisti ospiti, in una se- NE Rest, I Leave It To The Poor)… nuovo disco Atlas Sound (Logos) e un inte- quenza ininterrotta di eventi, dal pomerig- ro disco nuovo dei Deerhunter (Weird Era gio a notte inoltrata. -

Save the Bay's San Francisco Bay Watershed Curriculum

San Francisco Bay Watershed Curriculum A Collection of Activities and Action Projects About the San Francisco Bay Watershed for Middle and High School Students Save The Bay’s San Francisco Bay Watershed Curriculum TABLE OF CONTENTS User’s GuideGuide................................................................................................................iii Welcome to Your Watershed The Bay and You, A Watershed Jounal........................................................................1 The San Francisco Bay’s Watershed in Your Hand....................................................7 Wetlands in a Pan, A Watershed Model Demonstrating the Functions of Wetlands..................10 WhenRain Hits the Land, Experimenting with Runoff..................................................16 The Bay Starts Here! Understanding Your Watershed....................................................28 Mapping Your Watershed, Exploring Maps of California...............................................38 Three Ways to be 3D, Understanding Topographic Maps............................................44 It Goes with the Flow...........................................................................................53 Geology of the San Francisco Bay and Its Wealth of Resources Peanut Butter and Jelly Geology, A Study of Faults and Geologic Activity.............................68 Liquefaction in Action, Bay Fill and Earthquakes: The Hidden Dangers............................77 Dirt All Around, A Study of Erosion and Sedimentation.................................................82 -

David Byrne and Brian Eno -- Everything That Happens Will

The dimming of the light makes the picture clearer It’s just an old photograph There’s nothing to hide when the world was just beginning I memorized a face so it’s not forgotten I hear the wind whistlin’ Come back anytime And we’ll mix our lives together Heaven knows- what keeps mankind alive Ev’ry hand- goes searching for its partner In crime- under chairs and behind tables Connecting- to places we have known (I’m looking for a) Home- where the wheels are turning Home- why I keep returning Home- where my world is breaking in two Home- with the neighbors fighting Home- always so exciting H ome- were my parents telling the truth? Home – such a funny feeling Home – no-one ever speaking Home- with our bodies touching Home- and the cam’ras watching Home- will infect what ever you do We’re Home- comes to life from outa the blue Tiny little boats on a beach at sunset I took a drink from a jar & into my head familiar smells and flavors Vehicles are stuck on the plains of heaven I see their wheels spinning round & ev’rywhere I can hear those people saying That the eye- is the measure of the man You can fly- from the stuff that still surrounds you We’re home- and the band keeps marchin’ on Connecting- to ev’ry living soul Compassion- for things I’ll never know When the lake’s on fire With all the world’s desires When he shakes the stars above When we lose the ones we love When the seasons lose their grip When the tighrope walker slips I’m counting all the possibilities When the past becomes the now When the lost becomes the found When we fall in -

The Strength of the Pines

The Strength of the Pines By Edison Marshall THE STRENGTH OF THE PINES BOOK ONE THE CALL OF THE BLOOD I Bruce was wakened by the sharp ring of his telephone bell. He heard its first note; and its jingle seemed to continue endlessly. There was no period of drowsiness between sleep and wakefulness; instantly he was fully aroused, in complete control of all his faculties. And this is not especially common to men bred in the security of civilization. Rather it is a trait of the wild creatures; a little matter that is quite necessary if they care at all about living. A deer, for instance, that cannot leap out of a mid-afternoon nap, soar a fair ten feet in the air, and come down with legs in the right position for running comes to a sad end, rather soon, in a puma's claws. Frontiersmen learn the trait too; but as Bruce was a dweller of cities it seemed somewhat strange in him. The trim, hard muscles were all cocked and primed for anything they should be told to do. Then he grunted rebelliously and glanced at his watch beneath the pillow. He had gone to bed early; it was just before midnight now. "I wish they'd leave me alone at night, anyway," he muttered, as he slipped on his dressing gown. He had no doubts whatever concerning the nature of this call. There had been one hundred like it during the previous month. His foster father had recently died, his estate was being settled up, and Bruce had been having a somewhat strenuous time with his creditors.