Interview with Joan Pope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Police Whistleblower in a Corrupt Political System

A police whistleblower in a corrupt political system Frank Scott Both major political parties in West Australia espouse open and accountable government when they are in opposition, however once their side of politics is able to form Government, the only thing that changes is that they move to the opposite side of the Chamber and their roles are merely reversed. The opposition loves the whistleblower while the government of the day loathes them. It was therefore refreshing to see that in 2001 when the newly appointed Attorney General in the Labor government, Mr Jim McGinty, promised that his Government would introduce whistleblower protection legislation by the end of that year. He stated that his legislation would protect those whistleblowers who suffered victimization and would offer some provisions to allow them to seek compensation. How shallow those words were; here we are some sixteen years later and yet no such legislation has been introduced. Below I have written about the effects I suffered from trying to expose corrupt senior police officers and the trauma and victimization I suffered which led to the loss of my livelihood. Whilst my efforts to expose corrupt police officers made me totally unemployable, those senior officers who were subject of my allegations were promoted and in two cases were awarded with an Australian Police Medal. I describe my experiences in the following pages in the form of a letter to West Australian parliamentarian Rob Johnson. See also my article “The rise of an organised bikie crime gang,” September 2017, http://www.bmartin.cc/dissent/documents/Scott17b.pdf 1 Hon. -

Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1

FAIRFIELD COUNTY CEMETERIES VOLUME II (Church Cemeteries in the Eastern Section of the County) Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church This book covers information on graves found in church cemeteries located in the eastern section of Fairfield County, South Carolina as of January 1, 2008. It also includes information on graves that were not found in this survey. Information on these unfound graves is from an earlier survey or from obituaries. These unfound graves are noted with the source of the information. Jonathan E. Davis July 1, 2008 Map iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1 Bethesda Methodist Church Cemetery 26 Centerville Cemetery 34 Concord Presbyterian Church Cemetery 43 Longtown Baptist Church Cemetery 62 Longtown Presbyterian Church Cemetery 65 Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church Cemetery 73 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – New 86 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 91 New Buffalo Cemetery 92 Old Fellowship Presbyterian Church Cemetery 93 Pine Grove Cemetery 95 Ruff Chapel Cemetery 97 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – New 99 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 102 St. Stephens Episcopal Church Cemetery 112 White Oak A. R. P. Church Cemetery 119 Index 125 ii iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery This cemetery is located on Highway 34 about 1 mile west of Ridgeway. Albert, Charlie Anderson, Joseph R. November 27, 1911 – October 25, 1977 1912 – 1966 Albert, Jessie L. Anderson, Margaret E. December 19, 1914 – June 29, 1986 September 22, 1887 – September 16, 1979 Albert, Liza Mae Arndt, Frances C. December 17, 1913 – October 22, 1999 June 16, 1922 – May 27, 2003 Albert, Lois Smith Arndt, Robert D., Sr. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

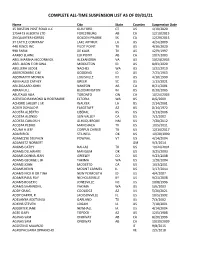

Complete All-Time Suspension List As of 08/07/2021

COMPLETE ALL-TIME SUSPENSION LIST AS OF 09/01/21 Name City State Country Suspension Date 15 BOSTON POST ROAD LLC GUILFORD CT US 1/10/2020 1754473 ALBERTA LTD FORESTBURG AB CA 12/10/2015 2N QUARTER HORSES GOLDEN PRAIRIE SK CA 12/29/2015 3T CATTLE COMPANY LAKE ARTHUR LA US 4/24/2009 440 FENCE INC PILOT POINT TX US 4/30/2020 990 FARM DE KALB TX US 12/9/1997 AARBO ELAINE ELK POINT AB CA 10/7/2003 ABEL MARSHA MCCORMICK ALEXANDRIA VA US 10/24/2003 ABEL JASON E OR GINA MIDDLETON ID US 8/03/2020 ABELLERA JUDGE NACHES WA US 1/22/2010 ABERCROMBIE C M GOODING ID US 7/23/1963 ABERNATHY MONICA LOUISVILLE KY US 4/10/1990 ABIKHALED CATHEY GREER SC US 1/13/2021 ABILDGAARD JOHN NANTON AB CA 8/21/2001 ABRAM JILL BLOOMINGTON IN US 8/30/2005 ABUTALIB ALIA TORONTO ON CA 10/24/2003 ACEVEDO RAYMOND & ROSEMARIE ELTOPIA WA US 8/6/2009 ACHORD SHELBY L SR WALKER LA US 2/14/2001 ACKER DONALD R FLAGSTAFF AZ US 8/14/1972 ACOSTA ALBERTO LIBERAL KS US 3/13/2006 ACOSTA ALONSO SUN VALLEY CA US 7/3/2002 ACOSTA CARLOS H ALBUQUERQUE NM US 7/20/2012 ACOSTA PEDRO MANCHACA TX US 10/5/2011 ACUNA A JEFF CORPUS CHRISTI TX US 12/14/2017 ADAIR RICK STILWELL OK US 10/20/1999 ADAMCZYK STEPHEN POWNAL VT US 4/14/2004 ADAMIETZ NORBERT GM 9/3/2014 ADAMS CATHY DALLAS TX US 10/24/2001 ADAMS DELAWARE MANGUM OK US 3/25/2003 ADAMS DONNA JEAN GREELEY CO US 9/23/2008 ADAMS GEORGE L JR YAKIMA WA US 1/28/2004 ADAMS JOHN MODESTO CA US 10/3/2001 ADAMS KEVIN MOUNT CARMEL IL US 3/17/2014 ADAMS NICK R OR TINA NEW PLYMOUTH ID US 4/4/2007 ADAMS PAUL RAY NICHOLASVILLE KY US 9/23/2008 ADAMS ROGER C JONESVILLE -

Ccies-Ki-Pdf File Creator.Vp

ConContents tin uum Com plete In ter na tion al En cy clo pe dia of Sexuality • THE • CONTINUUM Complete International ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SEXUALITY • ON THE WEB AT THE KINSEY IN STI TUTE • https://kinseyinstitute.org/collections/archival/ccies.php RAYMOND J. NOONAN, PH.D., CCIES WEBSITE EDITOR En cyc lo ped ia Content Copyr ight © 2004-2006 Con tin uum In ter na tion al Pub lish ing Group. Rep rinted under license to The Kinsey Insti tute. This Ency c lope dia has been made availa ble on line by a joint effort bet ween the Ed itors, The Kinsey Insti tute, and Con tin uum In ter na tion al Pub lish ing Group. This docu ment was downloaded from CCIES at The Kinsey In sti tute, hosted by The Kinsey Insti tute for Research in Sex, Gen der, and Rep ro duction, Inc. Bloomington, In di ana 47405. Users of this website may use downloaded content for non-com mercial ed u ca tion or re search use only. All other rights reserved, includ ing the mirror ing of this website or the placing of any of its content in frames on outside websites. Except as previ ously noted, no part of this book may be repro duced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans mitted, in any form or by any means, elec tronic, mechan ic al, pho to copyi ng, re cord ing, or oth erw ise, with out the writt en per mis sion of the pub lish ers. Ed ited by: ROBER T T. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Large Commercial-Industrial and Tax - Exempt Users As of 7/10/2018

Large Commercial-Industrial and Tax - Exempt Users as of 7/10/2018 User Account User Charge Facility Name Address City Zip Number Classification 20600 208 South LaSalle LCIU 208 S LaSalle Street Chicago 60604 27686 300 West Adams Management, LLC LCIU 300 W Adams Street Chicago 60606 27533 5 Rabbit Brewery LCIU 6398 W 74th Street Bedford Park 60638 27902 9W Halo OpCo L.P. LCIU 920 S Campbell Avenue Chicago 60612 11375 A T A Finishing Corp LCIU 8225 Kimball Avenue Skokie 60076 10002 Aallied Die Casting Co. of Illinois LCIU 3021 Cullerton Drive Franklin Park 60131 26752 Abba Father Christian Center TXE 2056 N Tripp Avenue Chicago 60639 26197 Abbott Molecular, Inc. LCIU 1300 E Touhy Avenue Des Plaines 60018 24781 Able Electropolishing Company LCIU 2001 S Kilbourn Avenue Chicago 60623 26702 Abounding in Christ Love Ministries, Inc. TXE 14620 Lincoln Avenue Dolton 60419 16259 Abounding Life COGIC TXE 14615 Mozart Avenue Posen 60469 25290 Above & Beyond Black Oxide Inc LCIU 1027-29 N 27th Avenue Melrose Park 60160 18063 Abundant Life MB Church TXE 2306 W 69th Street Chicago 60636 16270 Acacia Park Evangelical Lutheran Church TXE 4307 N Oriole Avenue Norridge 60634 13583 Accent Metal Finishing Co. LCIU 9331 W Byron Street Schiller Park 60176 26289 Access Living TXE 115 W Chicago Avenue Chicago 60610 11340 Accurate Anodizing LCIU 3130 S Austin Blvd Cicero 60804 11166 Ace Anodizing & Impregnating Inc LCIU 4161 Butterfield Road Hillside 60162 27678 Acme Finishing Company, LLC LCIU 1595 E Oakton Street Elk Grove Village 60007 18100 Addison Street -

Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, C.1000-1300

1 PAPAL OVERLORDSHIP AND PROTECTIO OF THE KING, c.1000-1300 Benedict Wiedemann UCL Submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2017 2 I, Benedict Wiedemann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, c.1000-1300 Abstract This thesis focuses on papal overlordship of monarchs in the middle ages. It examines the nature of alliances between popes and kings which have traditionally been called ‘feudal’ or – more recently – ‘protective’. Previous scholarship has assumed that there was a distinction between kingdoms under papal protection and kingdoms under papal overlordship. I argue that protection and feudal overlordship were distinct categories only from the later twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Before then, papal-royal alliances tended to be ad hoc and did not take on more general forms. At the beginning of the thirteenth century kingdoms started to be called ‘fiefs’ of the papacy. This new type of relationship came from England, when King John surrendered his kingdoms to the papacy in 1213. From then on this ‘feudal’ relationship was applied to the pope’s relationship with the king of Sicily. This new – more codified – feudal relationship seems to have been introduced to the papacy by the English royal court rather than by another source such as learned Italian jurists, as might have been expected. A common assumption about how papal overlordship worked is that it came about because of the active attempts of an over-mighty papacy to advance its power for its own sake. -

Flora of the Illinois Audubon Society's Lusk Creek Property in Pope

FLORA OF THE ILLINOIS AUDUBON SOCIETY’S LUSK CREEK PROPERTY IN POPE COUNTY, ILLINOIS Report to the Illinois Audubon Society by John White Ecological Services Flora of the Illinois Audubon Society’s Lusk Creek Property in Pope County, Illinois Summary ...................................................1 I. Introduction ...............................................2 Purpose...............................................2 Study area .............................................2 Procedure .............................................2 II. Inventory of the flora........................................3 Scientific name.........................................3 Common name .........................................3 Nativity...............................................3 Abundance ............................................4 Vegetation management concern ...........................5 Species documented by the present study.....................6 Species reported by Mark Basinger .........................7 Species reported by Bill Hopkins ...........................7 Habitat................................................7 Notes.................................................8 Treatment of varieties....................................8 Table 1: Flora of the Illinois Audubon Society’s Lusk Creek property . 10 III. Analysis of the flora .......................................31 Species documented by the present study and by Mark Basinger . 31 Bill Hopkins’ floristic inventory ...........................32 Botanical hotspots......................................33 -

The Iliad of Homer by Homer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad of Homer by Homer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Iliad of Homer Author: Homer Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 6130] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ILIAD OF HOMER*** The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope, with notes by the Rev. Theodore Alois Buckley, M.A., F.S.A. and Flaxman's Designs. 1899 Contents INTRODUCTION. ix POPE'S PREFACE TO THE ILIAD OF HOMER . xlv BOOK I. .3 BOOK II. 41 BOOK III. 85 BOOK IV. 111 BOOK V. 137 BOOK VI. 181 BOOK VII. 209 BOOK VIII. 233 BOOK IX. 261 BOOK X. 295 BOOK XI. 319 BOOK XII. 355 BOOK XIII. 377 BOOK XIV. 415 BOOK XV. 441 BOOK XVI. 473 BOOK XVII. 513 BOOK XVIII. 545 BOOK XIX. 575 BOOK XX. 593 BOOK XXI. 615 BOOK XXII. 641 BOOK XXIII. 667 BOOK XXIV. 707 CONCLUDING NOTE. 747 Illustrations HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE. .6 MARS. 13 MINERVA REPRESSING THE FURY OF ACHILLES. 16 THE DEPARTURE OF BRISEIS FROM THE TENT OF ACHILLES. 23 THETIS CALLING BRIAREUS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JUPITER. 27 THETIS ENTREATING JUPITER TO HONOUR ACHILLES. 32 VULCAN. 35 JUPITER. 38 THE APOTHEOSIS OF HOMER. 39 JUPITER SENDING THE EVIL DREAM TO AGAMEMNON. 43 NEPTUNE. 66 VENUS, DISGUISED, INVITING HELEN TO THE CHAMBER OF PARIS. -

Chick-Fil-A Vidalia Road Race Team Challenge

Chick-fil-A Vidalia Road Race Team Challenge Cup 2018 Organization/Team Last Name First Name Event Team Total Altamaha Bank and Trust Butler Carol 1 Mile Altamaha Bank and Trust Marsh Sam 5K Altamaha Bank and Trust McCoy Michaela 1 Mile Altamaha Bank and Trust Noles Valerie 5K 4 Ameris Bank Alamilla Castro Irene 1 Mile Ameris Bank Arnold Palmer 1 Mile Ameris Bank Cleghorn Eli 1 Mile Ameris Bank Cleghorn Gabe 1 Mile Ameris Bank Cleghorn Jake 1 Mile Ameris Bank Cleghorn Jasie 1 Mile Ameris Bank DeLoach Shree 1 Mile Ameris Bank Howell Cindy 1 Mile Ameris Bank Howell Lindsey 1 Mile Ameris Bank Humphrey Anna 1 Mile Ameris Bank Humphrey Bobbie 1 Mile Ameris Bank Humphrey Mark 1 Mile Ameris Bank Hutcheson Elaina 1 Mile Ameris Bank Kight Jennifer 1 Mile Ameris Bank King Belinda 1 Mile Ameris Bank Morgan Susan 1 Mile Ameris Bank Robins Renee 1 Mile Ameris Bank Strickland Lisa 1 Mile 18 Calvary On Aimwell Clark Jennifer 5K Calvary On Aimwell Clark Lee 5K Calvary On Aimwell Foster Chris 5K Calvary On Aimwell Green Diane 5K Calvary On Aimwell Green Efton 5K Calvary On Aimwell Halama Ethan 1 Mile Calvary On Aimwell Helms MJ 5K Calvary On Aimwell Lane Michael 5K Calvary On Aimwell martinez sonia 1 Mile 9 Chick-fil-A Vidalia Beasley Bryanna 1 Mile Chick-fil-A Vidalia Brown Marissa 5K Chick-fil-A Vidalia Cruz Danielle 1 Mile Chick-fil-A Vidalia Escalara Andy 1 Mile Chick-fil-A Vidalia Kirby Brandon 5K Chick-fil-A Vidalia McCullough Joy 1 Mile Chick-fil-A Vidalia McDade Britt 5K Chick-fil-A Vidalia McDade Candace 1 Mile Chick-fil-A Vidalia McDade Hamp -

Interim Assessment of the VAL Automated Guideway Transit System

. U M TA-M A-06-0069-8 1 -3 ‘-TSC-U MTA-81 -34 Interim Assessment of the HE VAL Automated Guideway 1 8.5 .*37 Transit System no dot- TSC- *- 1J i^T 81-34 U.S. Department of Transportation Ministere des Transports Transportation Systems Center Institut de Recherche Cambridge MA 02142 des Transports B.P. 2894110 Arcueil November 1981 Interim Report This document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161. U.S. Department of Transportation Urban Mass Transportation Administration Secretariat d Etat aupr£ du Ministere des T ransports et de Office of Technology Development I 'Amenagement du and Deployment Territoire (Transports' Washington DC 20590 75775 Pans Cedev 16 . NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse pro- ducts or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. Technical Report DocumentatiaeJ^A**^ 3. Recipient's Cotalog No. 1. Report No. 2. Covommont Acctition No. UMTA-HA-06-0069-81-3 PB 82-163783 Report 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Dote Interim Assessment of the VAL Automated November 1981 Guideway Transit System. 6. Performing Organization Code DTS-723 6. Performing Orgonization Report No. 7. Author's) DOT-TSC-UMTA-81-34 G. Anagnostopoulos 10. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address Work Unit No. (TRAIS) U.S. Department of Transportation* MA-06-0069 (UM136/R1764) Transportation Systems Center 11.