Pope's Versification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Blackmore Country (1906)

I II i II I THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES IN THE SAME SERIES PRICE 6/- EACH THE SCOTT COUNTRY THE BURNS COUNTRY BY W. S. CROCKETT BY C. S. DOOGALL Minister of Twccdsmuir THE THE THACKERAY COUNTRY CANTERBURY PILGRIMAGES BY LEWIS MELVILLE BY II. SNOWDEN WARD THE INQOLDSBY COUNTRY THE HARDY COUNTRY BY CHAS. G. HAKI'ER BY CHAS. G. HARPER PUBLISHED BY ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK, SOHO SQUARE, LONDON Zbc pWQVimnQC Series CO THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY s^- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/blackmorecountryOOsneliala ON THE LYN, BELOW BRENDON. THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY BY F. J. SNELL AUTHOR OF 'A BOOK OF exmoob"; " kably associations of archbishop temple," etc. EDITOR of " UEMORIALS OF OLD DEVONSHIRE " WITH FIFTY FULL -PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY C. W. BARNES WARD LONDON ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1906 " So holy and so perfect is my love, That I shall think it a most plenteous crop To glean the broken ears after the man That the main harvest reaps." —Sir Phiup SroNEY. CORRIGENDA Page 22, line 20, for " immorality " read " morality." „ 128, „ 2 1, /or "John" r^a^/" Jan." „ 131, „ 21, /<7r "check" r?a^ "cheque." ; PROLOGUE The " Blackmore Country " is an expression requiring some amount of definition, as it clearly will not do to make it embrace the whole of the territory which he annexed, from time to time, in his various works of fiction, nor even every part of Devon in which he has laid the scenes of a romance. -

A Police Whistleblower in a Corrupt Political System

A police whistleblower in a corrupt political system Frank Scott Both major political parties in West Australia espouse open and accountable government when they are in opposition, however once their side of politics is able to form Government, the only thing that changes is that they move to the opposite side of the Chamber and their roles are merely reversed. The opposition loves the whistleblower while the government of the day loathes them. It was therefore refreshing to see that in 2001 when the newly appointed Attorney General in the Labor government, Mr Jim McGinty, promised that his Government would introduce whistleblower protection legislation by the end of that year. He stated that his legislation would protect those whistleblowers who suffered victimization and would offer some provisions to allow them to seek compensation. How shallow those words were; here we are some sixteen years later and yet no such legislation has been introduced. Below I have written about the effects I suffered from trying to expose corrupt senior police officers and the trauma and victimization I suffered which led to the loss of my livelihood. Whilst my efforts to expose corrupt police officers made me totally unemployable, those senior officers who were subject of my allegations were promoted and in two cases were awarded with an Australian Police Medal. I describe my experiences in the following pages in the form of a letter to West Australian parliamentarian Rob Johnson. See also my article “The rise of an organised bikie crime gang,” September 2017, http://www.bmartin.cc/dissent/documents/Scott17b.pdf 1 Hon. -

Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1

FAIRFIELD COUNTY CEMETERIES VOLUME II (Church Cemeteries in the Eastern Section of the County) Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church This book covers information on graves found in church cemeteries located in the eastern section of Fairfield County, South Carolina as of January 1, 2008. It also includes information on graves that were not found in this survey. Information on these unfound graves is from an earlier survey or from obituaries. These unfound graves are noted with the source of the information. Jonathan E. Davis July 1, 2008 Map iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1 Bethesda Methodist Church Cemetery 26 Centerville Cemetery 34 Concord Presbyterian Church Cemetery 43 Longtown Baptist Church Cemetery 62 Longtown Presbyterian Church Cemetery 65 Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church Cemetery 73 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – New 86 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 91 New Buffalo Cemetery 92 Old Fellowship Presbyterian Church Cemetery 93 Pine Grove Cemetery 95 Ruff Chapel Cemetery 97 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – New 99 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 102 St. Stephens Episcopal Church Cemetery 112 White Oak A. R. P. Church Cemetery 119 Index 125 ii iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery This cemetery is located on Highway 34 about 1 mile west of Ridgeway. Albert, Charlie Anderson, Joseph R. November 27, 1911 – October 25, 1977 1912 – 1966 Albert, Jessie L. Anderson, Margaret E. December 19, 1914 – June 29, 1986 September 22, 1887 – September 16, 1979 Albert, Liza Mae Arndt, Frances C. December 17, 1913 – October 22, 1999 June 16, 1922 – May 27, 2003 Albert, Lois Smith Arndt, Robert D., Sr. -

Studies in the Work of Colley Cibber

BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS HUMANISTIC STUDIES Vol. 1 October 1, 1912 No. 1 STUDIES IN THE WORK OF COLLEY CIBBER BY DE WITT C.:'CROISSANT, PH.D. A ssistant Professor of English Language in the University of Kansas LAWRENCE, OCTOBER. 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CONTENTS I Notes on Cibber's Plays II Cibber and the Development of Sentimental Comedy Bibliography PREFACE The following studies are extracts from a longer paper on the life and work of Cibber. No extended investigation concerning the life or the literary activity of Cibber has recently appeared, and certain misconceptions concerning his personal character, as well as his importance in the development of English literature and the literary merit of his plays, have been becoming more and more firmly fixed in the minds of students. Cibber was neither so much of a fool nor so great a knave as is generally supposed. The estimate and the judgment of two of his contemporaries, Pope and Dennis, have been far too widely accepted. The only one of the above topics that this paper deals with, otherwise than incidentally, is his place in the development of a literary mode. While Cibber was the most prominent and influential of the innovators among the writers of comedy of his time, he was not the only one who indicated the change toward sentimental comedy in his work. This subject, too, needs fuller investigation. I hope, at some future time, to continue my studies in this field. This work was suggested as a subject for a doctor's thesis, by Professor John Matthews Manly, while I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago a number of years ago, and was con• tinued later under the direction of Professor Thomas Marc Par- rott at Princeton. -

HLB 20-3+4 Johnson BOOK.Indb

Johnson on Blackmore, Pope, Shakespeare—and Johnson The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Engell, James. 2011. Johnson on Blackmore, Pope, Shakespeare— and Johnson. In Johnson After Three Centuries: New Light on Texts and Contexts, ed. Thomas A. Horrocks and Howard D. Weinbrot, special issue, Harvard Library Bulletin 20(3-4): 51-61. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8492407 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Johnson on Blackmore, Pope, Shakespeare—and Johnson James Engell Readers . are to impute to me whatever pleasure or weariness they may #nd in the perusal of Blackmore, Watts, Pomfret, and Yalden." his essay treats Johnson primarily through Sir Richard Blackmore, a novel path, and since many readers may not be acquainted with Blackmore’s work, Tnor is there a compelling reason why anyone should be, I apologize at the outset. Yet, this path to Johnson provides understanding of his cherished personal values and of his deeply held principles of criticism. It reveals a central con$ict holding in tension Johnson’s personal life with his professional career. I should like to present a piece of Johnson’s writing that has, for %%! years, remained overlooked. On the surface, reasons appear for that. He wrote in "&'( about an author whose reputation had for decades been dark. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Mask, Mirror, and Weapon:Pope's Versatile Satire

Grant 1 Mask, Mirror, and Weapon: Pope’s Versatile Satire Nina Grant The history and life of a writer are often a monumental influence on their works and opinions. Alexander Pope is no exception, and he had a great deal of experience to draw from. Pope was a person closely acquainted with hardship from a multitude of sources, including reli- gious discrimination, harsh critiques of his writing, and an extreme physical disability. Instead of dwelling on miserable events and pouring his suffering into his work emotionally, Pope uses his poetry to correct the prejudice thrown his way through calculated vocabulary choices and direct analogies of those for whom he had ample distaste. Pope elevates his most desirable qualities while simultaneously criticizing and pushing down his rivals and enemies, all under the cover of satire and fiction. Through his writing, Pope reverses the multitude of prejudices that he has ex- perienced through judgement of his faith, his writing, and his physicality, both to preserve his dignity and status as well as to pursue the contentedness that he was never able to obtain. From a young age, Pope endured a physical disability that left him at under five feet in height. This is something that was clearly a struggle for him both as a label and a physical com- plication, because he experienced several severe health conditions as a result (Deutsch 2). He also expressed his pain, both physical and emotional, in several letters to the close people in his life. Damrosch examines these correspondences with special attention to one addressed to Bath- urst, in which Pope lamentingly describes his body as a burden to himself and others, claiming it is as useless as dead weight (21). -

Harper Dissertation 20129.Pdf

Copyright by David Andrew Harper 2012 The Dissertation Committee for David Andrew Harper Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Curb’d Enthusiasms: Critical Interventions in the Reception of Paradise Lost, 1667-1732 Committee: John Rumrich, Supervisor Lance Bertelsen Douglas Bruster Jack Lynch Leah Marcus Curb’d Enthusiasms: Critical Interventions in the Reception of Paradise Lost, 1667-1732 by David Andrew Harper, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2012 Curb’d Enthusiasms: Critical Interventions in the Reception of Paradise Lost, 1667-1732 David Andrew Harper, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: John Rumrich Although recent critics have attempted to push the canonization of Paradise Lost ever further into the past, the early reception of Milton’s great poem should be treated as a process rather than as an event inaugurated by the pronouncement of a poet laureate or lord. Inevitably linked to Milton’s Restoration reputation as spokesman for the Protectorate and regicides, Paradise Lost’s reception in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries is marked by a series of approaches and retreats, repressions and recoveries. This dissertation examines the critical interventions made by P.H. (traditionally identified as Patrick Hume), John Dennis, Joseph Addison, and Richard Bentley into the reception history of a poem burdened by political and religious baggage. It seeks to illuminate the manner in which these earliest commentators sought to separate Milton’s politics from his poem, rendering the poem “safe” by removing it from contemporary political discourse. -

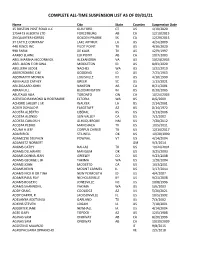

Complete All-Time Suspension List As of 08/07/2021

COMPLETE ALL-TIME SUSPENSION LIST AS OF 09/01/21 Name City State Country Suspension Date 15 BOSTON POST ROAD LLC GUILFORD CT US 1/10/2020 1754473 ALBERTA LTD FORESTBURG AB CA 12/10/2015 2N QUARTER HORSES GOLDEN PRAIRIE SK CA 12/29/2015 3T CATTLE COMPANY LAKE ARTHUR LA US 4/24/2009 440 FENCE INC PILOT POINT TX US 4/30/2020 990 FARM DE KALB TX US 12/9/1997 AARBO ELAINE ELK POINT AB CA 10/7/2003 ABEL MARSHA MCCORMICK ALEXANDRIA VA US 10/24/2003 ABEL JASON E OR GINA MIDDLETON ID US 8/03/2020 ABELLERA JUDGE NACHES WA US 1/22/2010 ABERCROMBIE C M GOODING ID US 7/23/1963 ABERNATHY MONICA LOUISVILLE KY US 4/10/1990 ABIKHALED CATHEY GREER SC US 1/13/2021 ABILDGAARD JOHN NANTON AB CA 8/21/2001 ABRAM JILL BLOOMINGTON IN US 8/30/2005 ABUTALIB ALIA TORONTO ON CA 10/24/2003 ACEVEDO RAYMOND & ROSEMARIE ELTOPIA WA US 8/6/2009 ACHORD SHELBY L SR WALKER LA US 2/14/2001 ACKER DONALD R FLAGSTAFF AZ US 8/14/1972 ACOSTA ALBERTO LIBERAL KS US 3/13/2006 ACOSTA ALONSO SUN VALLEY CA US 7/3/2002 ACOSTA CARLOS H ALBUQUERQUE NM US 7/20/2012 ACOSTA PEDRO MANCHACA TX US 10/5/2011 ACUNA A JEFF CORPUS CHRISTI TX US 12/14/2017 ADAIR RICK STILWELL OK US 10/20/1999 ADAMCZYK STEPHEN POWNAL VT US 4/14/2004 ADAMIETZ NORBERT GM 9/3/2014 ADAMS CATHY DALLAS TX US 10/24/2001 ADAMS DELAWARE MANGUM OK US 3/25/2003 ADAMS DONNA JEAN GREELEY CO US 9/23/2008 ADAMS GEORGE L JR YAKIMA WA US 1/28/2004 ADAMS JOHN MODESTO CA US 10/3/2001 ADAMS KEVIN MOUNT CARMEL IL US 3/17/2014 ADAMS NICK R OR TINA NEW PLYMOUTH ID US 4/4/2007 ADAMS PAUL RAY NICHOLASVILLE KY US 9/23/2008 ADAMS ROGER C JONESVILLE -

Ccies-Ki-Pdf File Creator.Vp

ConContents tin uum Com plete In ter na tion al En cy clo pe dia of Sexuality • THE • CONTINUUM Complete International ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SEXUALITY • ON THE WEB AT THE KINSEY IN STI TUTE • https://kinseyinstitute.org/collections/archival/ccies.php RAYMOND J. NOONAN, PH.D., CCIES WEBSITE EDITOR En cyc lo ped ia Content Copyr ight © 2004-2006 Con tin uum In ter na tion al Pub lish ing Group. Rep rinted under license to The Kinsey Insti tute. This Ency c lope dia has been made availa ble on line by a joint effort bet ween the Ed itors, The Kinsey Insti tute, and Con tin uum In ter na tion al Pub lish ing Group. This docu ment was downloaded from CCIES at The Kinsey In sti tute, hosted by The Kinsey Insti tute for Research in Sex, Gen der, and Rep ro duction, Inc. Bloomington, In di ana 47405. Users of this website may use downloaded content for non-com mercial ed u ca tion or re search use only. All other rights reserved, includ ing the mirror ing of this website or the placing of any of its content in frames on outside websites. Except as previ ously noted, no part of this book may be repro duced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans mitted, in any form or by any means, elec tronic, mechan ic al, pho to copyi ng, re cord ing, or oth erw ise, with out the writt en per mis sion of the pub lish ers. Ed ited by: ROBER T T. -

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: the Survival of the London Theatre Community

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: The Survival of the London Theatre Community By Mary Alex Staude Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2018 Approved: (Signature of Advisor) Acknowledgements I would like to thank Reid Barbour for his support, guidance, and advice throughout this process. Without his help, this project would not be what it is today. Thanks also to Laura Pates, Adam Maxfield, Alex LaGrand, Aubrey Snowden, Paul Smith, and Playmakers Repertory Company. Also to Diane Naylor at Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Much love to friends and family for encouraging my excitement about this project. Particular thanks to Nell Ovitt for her gracious enthusiasm, and to Hannah Dent for her unyielding support. I am grateful for the community around me and for the communities that came before my time. Preface Mary Alex Staude worked on Twelfth Night 2017 with Alex LaGrand who worked on King Lear 2016 with Zack Powell who worked on Henry IV Part II 2015 with John Ahlin who worked on Macbeth 2000 with Jerry Hands who worked on Much Ado About Nothing 1984 with Derek Jacobi who worked on Othello 1964 with Laurence Olivier who worked on Romeo and Juliet 1935 with Edith Evans who worked on The Merry Wives of Windsor 1918 with Ellen Terry who worked on The Winter’s Tale 1856 with Charles Kean who worked on Richard III 1776 with David Garrick who worked on Hamlet 1747 with Charles Macklin who worked on Henry IV 1738 with Colley Cibber who worked on Julius Caesar 1707 with Thomas Betterton who worked on Hamlet 1661 with William Davenant who worked on Henry VIII 1637 with John Lowin who worked on Henry VIII 1613 with John Heminges who worked on Hamlet 1603 with William Shakespeare.