Delius's Leipzig Connections by Philip Jones 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European. A critical review By Berit Holth National Library of Norway Edvard Grieg, ca. 1858 Photo: Marcus Selmer Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, Leipzig ca. 1850 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg graduated from The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, 1862 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, 11 year old Alexander Grieg (1806-1875)(father) Gesine Hagerup Grieg (1814-1875)(mother) Cutout of a daguerreotype group. Responsible: Karl Anderson Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway Ole Bull (1810-1880) Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910) Wedding photo of Edvard & Nina Grieg (1845-1935), Copenhagen 1867 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard & Nina Grieg with friends in Copenhagen Owner: http://griegmuseum.no/en/about-grieg Capital of Norway from 1814: Kristiania name changed to Oslo Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway From Kvam, Hordaland Photo: Reidun Tveito Owner: National Library of Norway Owner: National Library of Norway Julius Röntgen (1855-1932), Frants Beyer (1851-1918) & Edvard Grieg at Løvstakken, June 1902 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives From Gudvangen, Sogn og Fjordane Photo: Berit Holth Gjendine’s lullaby by Edvard Grieg after Gjendine Slaalien (1871-1972) Owner: National Library of Norway Max Abraham (1831-1900), Oscar Meyer, Nina & Edvard Grieg, Leipzig 1889 Owner: Bergen Public Library. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

1 MISSA SOLEMNIS FOR CHOIR, ORGAN, SOLI, PIANO AND CELESTA ANDREAS HALLÉN I. KYRIE 9:23 choir II. GLORIA 15:46 choir, soli SATB III. CREDO 14:07 choir, tenor solo IV. SANCTUS 13:16 choir V. AGNUS DEI 10:06 choir, soli SATB Total playing time: 62:39 Soloists Pia-Karin Helsing, soprano Maria Forsström, alto Conny Thimander, tenor Andreas E. Olsson, bass Lars Nilsson, organ James Jenkins, piano Lars Sjöstedt, celesta 2 The Erik Westberg Vocal Ensemble Soprano Virve Karén (2) Jonatan Brundin (1,2) Linnea Pettersson (1) Olle Sköld (2) Christina Fridolfsson (1,2) Rickard Collin (1) Lotta Kuisma (1,2) Anders Bek (1,2) Alva Stern (1,2) Victoria Stanmore (2) Lars Nilsson, organ Alto James Jenkins, piano Kerstin Eriksson (2) Lars Sjöstedt, celesta Anu Arvola (2) Cecilia Grönfelt (1,2) (1) 11–12 October 2019 Katarina Karlsson (1,2) Kyrie, Sanctus Anna Risberg (1,2) Anna-Karin Lindström (1,2) (2) 28 February–1 March 2020 Gloria, Credo, Agnus Dei Tenor Anders Lundström (1) Anders Eriksson (2) Stefan Millgård (1,2) Adrian Rubin (2) Mattias Lundström (1,2) Örjan Larsson (1,2) Mischa Carlberg (1) Bass Martin Eriksson (1,2) Anders Sturk Steinwall (1) Andreas E. Olsson (1,2) Mikael Sandlund (2) 3 Andreas Hallén © The Music and Theatre Library of Sweden 4 A significant musical pioneer Johan [Johannes1] Andreas Hallén was born on 22 December 1846 in Göteborg (Gothenburg), Sweden. His musical talent was discovered at an early age and he took up playing the piano and later also the organ. As a teenager he set up a music society that gave a very successful concert, inspiring him to invest in becoming a professional musician. -

Grieg & Musical Life in England

Grieg & Musical Life in England LIONEL CARLEY There were, I would prop ose, four cornerstones in Grieg's relationship with English musicallife. The first had been laid long before his work had become familiar to English audiences, and the last was only set in place shortly before his death. My cornerstones are a metaphor for four very diverse and, you might well say, ve ry un-English people: a Bohemian viol inist, a Russian violinist, a composer of German parentage, and an Australian pianist. Were we to take a snapshot of May 1906, when Grieg was last in England, we would find Wilma Neruda, Adolf Brodsky and Percy Grainger all established as significant figures in English musicallife. Frederick Delius, on the other hand, the only one of thi s foursome who had actually been born in England, had long since left the country. These, then, were the four major musical personalities, each having his or her individual and intimate connexion with England, with whom Grieg established lasting friendships. There were, of course, others who com prised - if I may continue and then finally lay to rest my architectural metaphor - major building blocks in the Grieg/England edifice. But this secondary group, people like Francesco Berger, George Augener, Stop ford Augustus Brooke, for all their undoubted human charms, were firs t and foremost representatives of British institutions which in their own turn played an important role in Grieg's life: the musical establishment, publishing, and, perhaps unexpectedly religion. Francesco Berger (1834-1933) was Secretary of the Philharmonic Soci ety between 1884 and 1911, and it was the Philharmonic that had first prevailed upon the mature Grieg to come to London - in May 1888 - and to perform some of his own works in the capital. -

Bokvennen Julen 2018 18 90

Bokvennen julen 2018 18 90 Antikvariatet i sentrum - vis à vis Nasjonalgalleriet Bøker - Kart - Trykk - Manuskripter Catilina, Drama i tre Akter af Brynjolf Bjarme Christiania, 1850. Henrik Ibsens debut. kr. 100.000,- Nr. 90 Nr. 89 Nr. 87 Nr. 88 Nr. 91 ViV harharar ogsåoggsså etet godtgodo t utvalguuttvav llg avav IbsensIbIbsseens øvrigeøvrrige dramaer.ddrraammaeerr.. Bokvennen julen 2018 ! Julen 3 Skjønnlitteratur 5 #&),)4)!+&#!#)( 10 Sport og friluftsliv 12 Historie og reiser 14 Krigen 15 Kulturhistorie 16 Kunst og arkitektur 17 Lokalhistorie 18 Mat og drikke 20 Medisin 21 Naturhistorie - og vitenskap 23 Personhistorie 24 Samferdsel og sjøfart 25 !"#$" $$"$! # " Språk 26 %#$""$" " Varia 27 NORLIS ANTIKVARIAT AS Universitetsgaten 18, 0164 Oslo norlis.no 22 20 01 40 [email protected] Åpningstider: Mandag - Fredag 10 - 18 Lørdag: 10 - 16 Søndag: 12 - 16 Bestillingene blir ekspedert i den rekkefølge de innløper. Bøkene kan hentes i forretningen, eller tilsendes. Porto tilkommer. Vennligst oppgi kredittkortdetaljer ved tilsending. Faktura etter avtale (mot fakturagebyr kr. 50,-). Ingen rabatter på katalog-objekter. Våre kart, trykk og manuskripter har merverdiavgift beregnet i henhold til merverdiavgiftsloven § 20 b og er ikke fradragsberettiget som inngående avgift. Vi tar forbehold om trykkfeil. Katalogen legges også ut på nett. Følg med på våre facebook-sider (norlis.no) eller kontakt oss om du vil ha beskjed på e-post. Søndager: Bøker kr. 100,- Trykk og barnebøker kr. 50,- Neste salg på hollandsk vis fra torsdag 10. januar 2018. 1 18 90 Nr.Nr. 173173 - kr.kr. 2.500,-2.500,- Nr.N 1 - kr.k 1.250,- 1 250 Nr.Nr. 89 - kr.kr. 300,-300,- Nr.N 19 - kr.k 425,-425 Nr.NNr 23 - kr.kkr 300,-300 Nr. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

CHAN 9985 BOOK.Qxd 10/5/07 5:14 Pm Page 2

CHAN 9985 Front.qxd 10/5/07 4:50 pm Page 1 CHAN 9985 CHANDOS CHAN 9985 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 5:14 pm Page 2 Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) Poetic Tone-Pictures, Op. 3 11:45 1 1 Allegro ma non troppo 1:52 2 2 Allegro cantabile 2:19 3 3 Con moto 1:55 4 4 Andante con sentimento 3:17 Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht 5 5 Allegro moderato – Vivo 1:16 6 6 Allegro scherzando 0:49 Sonata, Op. 7 19:41 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur 7 I Allegro moderato – Allegro molto 4:43 8 II Andante molto – L’istesso tempo 4:54 9 III Alla Menuetto, ma poco più lento 3:26 10 IV Finale. Molto allegro – Presto 6:25 Seven fugues for piano (1861–62) 13:29 11 Fuga a 2. Allegro 1:01 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur 12 [Fuga a 2] 1:07 in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeur 13 Fuga a 3. Andante non troppo 2:11 Edvard Grieg in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur 14 Fuga a 3. Allegro 1:09 in A minor • in a-Moll • en la mineur 3 CHAN 9985 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 5:14 pm Page 4 Grieg: Sonata, Op. 7 etc. 15 Fuga a 4. Allegro non troppo 2:36 There were two principal strands in Edvard there, and he was followed by an entire in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur Grieg’s creative personality: the piano and cohort of composers-to-be, among them 16 Fuga a 3 voci. -

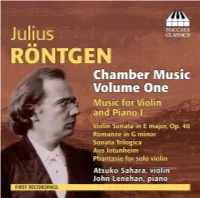

Toccata Classics TOCC0024 Notes

P JULIUS RÖNTGEN, CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME ONE – WORKS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO I by Malcolm MacDonald Considering his prominence in the development of Dutch concert music, and that he was considered by many of his most distinguished contemporaries to possess a compositional talent bordering on genius, the neglect that enveloped the huge output of Julius Röntgen for nearly seventy years after his death seems well-nigh inexplicable, or explicable only to the kind of aesthetic view that had heard of him as stylistically conservative, and equated conservatism as uninteresting and therefore not worth investigating. The recent revival of interest in his works has revealed a much more complex picture, which may be further filled in by the contents of the present CD. A distant relative of the physicist Conrad Röntgen,1 the discoverer of X-rays, Röntgen was born in 1855 into a highly musical family in Leipzig, a city with a musical tradition that stretched back to J. S. Bach himself in the first half of the eighteenth century, and that had been a byword for musical excellence and eminence, both in performance and training, since Mendelssohn’s directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Conservatoire in the 1830s and ’40s. Röntgen’s violinist father Engelbert, originally from Deventer in the Netherlands, was a member of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and its concert-master from 1873. Julius’ German mother was the pianist Pauline Klengel, sister of the composer Julius Klengel (father of the cellist-composer of the same name), who became his nephew’s principal tutor; the whole family belonged to the circle around the composer and conductor Heinrich von Herzogenberg and his wife Elisabet, whose twin passions were the revival of works by Bach and the music of their close friend Johannes Brahms. -

A History of the School of Music

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1952 History of the School of Music, Montana State University (1895-1952) John Roswell Cowan The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cowan, John Roswell, "History of the School of Music, Montana State University (1895-1952)" (1952). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2574. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2574 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI A KCSTOHY OF THE SCHOOL OP MUSIC MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY (1895-1952) by JOHN H. gOWAN, JR. B.M., Montana State University, 1951 Presented In partial fulfillment of the requirements for tiie degree of Master of Music Education MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1952 UMI Number EP34848 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, If material had to be removed, a note will Indicate the deletion. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

DELIUS BOOKLET:Bob.Qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1

DELIUS BOOKLET:bob.qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1 second piece, Summer Night on the River, is equally evocative, this time suggested by the river Loing that lay at the the story of a voodoo prince sold into slavery, based on an episode in the novel The Grandissimes by the American bottom of Delius’s garden near Fontainebleau, the kind of scene that might have been painted by some of the French writer George Washington Cable. The wedding dance La Calinda was originally a dance of some violence, leading to painters that were his contemporaries. hysteria and therefore banned. In the Florida Suite and again in Koanga it lacks anything of its original character. The opera Irmelin, written between 1890 and 1892, and the first attempt by Delius at the form, had no staged Koanga, a lyric drama in a prologue and three acts, was first heard in an incomplete concert performance at St performance until 1953, when Beecham arranged its production in Oxford. The libretto, by Delius himself, deals with James’s Hall in 1899. It was first staged at Elberfeld in 1904. With a libretto by Delius and Charles F. Keary, the plot The Best of two elements, Princess Irmelin and her suitors, none of whom please her, and the swine-herd who eventually wins is set on an eighteenth century Louisiana plantation, where the slave-girl Palmyra is the object of the attentions of her heart. The Prelude, designed as an entr’acte for the later opera Koanga, makes use of four themes from Irmelin. -

Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON & MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephones i Ticket Office J g k Ba^ 1492 Branch Exchange \ Administration Offices ) THIRTY- SECOND SEASON, 1912 AND 1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Tenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 27 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 613 — ** After the Symphony Concert ^^ a prolonging of musical pleasure by home-firelight awaits the owner of a "Baldwin." The strongest impressions of the concert season are linked w^ith Baldwintone, exquisitely exploited by pianists eminent in their art. Schnitzer, Pugno, Scharwenka, Bachaus De Pachmann! More than chance attracts the finely-gifted amateur to this keyboard. Among people who love good music, w^ho have a culti- vated knowledge of it, and who seek the best medium for producing it, the Baldwin is chief. In such an atmosphere it is as happily "at home" as are the Preludes of Chopin, the Liszt Rhapsodies upon a virtuoso's programme. THE BOOK OF THE BALDWIN free upon request. CHAS. F. LEONARD, 120 Boylston Street BOSTON, MASS. 614 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirty-second Season, 1912-1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Tak, E. Noack, S. CHICKERING THE STANDARD PIANO SINCE 1823 Piano of American make has been NOso favored by the musical pubHc as this famous old Boston make. The world's greatest musicians have demanded it and discriminating people have purchased it.