Literature Review Introduction 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAYORS, MAORI and EMPLOYMENT

The Jobs Letter No. 130 8 September 2000 Essential Information on an Essential Issue • More than fifty beneficiary advocates from Northland to Invercargill KEY met last week with Government Ministers, the Department of Work and Income (Winz) and Ministry of Social Policy (MSP). They discussed MAYORS MEET MAORI progress on a list of 123 recommendations of immediate changes that the advocates want to see Winz and other departments implement in AN EMPLOYMENT STRATEGY order to assist those living on a benefit. ADVOCATES MEET GOVERNMENT The Conference took place at Tatum Park near Levin, and was addressed by Ruth Dyson, Associate Minister of Social Services and Employment and CEG APPOINTMENT Parekura Horomia, Minister of Maori Affairs. The ministers later said that the INCOME AND JOB INSECURITY government “valued its ongoing relationship with the advocates...” CEOs Robert Reid, President of Unite! and spokesperson for the advocate groups says that the conference enabled a wide group to consider the recommendations from the advocates and to discuss what progress had been made on them by the departments. The meeting also included DIARY workshops with representatives from Winz, MSP, Department of La- 16 August 2000 bour, Ministry of Economic Development and Housing New Zealand. Representatives from the Labour, Alliance and Green Parties were Parliament’s finance committee endorses a policy that govern- invited to the final session of the conference. ment departments buy NZ-made goods and services “where cost There will now be regional meetings held between beneficiary advocate groups effective”. The Industrial Supplies and the Winz Regional Commissioners. Maori beneficiary advocates have Office, which filters government formed their own network and have been invited to be involved in the Winz purchasing, says that every $1m of import substitution saves 16 Maori structures. -

RTI Study by Steven Price

1 I INTRODUCTION Introducing the Official Information Bill to Parliament in 1981, the Minister of Justice called it "one of the most significant constitutional innovations to be made since the establishment of the office of the Ombudsmen in the early 1960s."1 Its goals were lofty: to "increase progressively the availability of official information" in order to promote democratic participation, political accountability and good government.2 Yet to hear some of the criticisms of the Official Information Act 1982 (OIA) now, one could be forgiven for wondering whether it has been much of an improvement over the Official Secrets Act 1951, which made releasing official information an offence.3 "Ministers and officials developed ways of routinely subverting the provisions of the Official Information Act", researcher Nicky Hager has written.4 "Journalists complain processing of requests takes too long, and accuse bureaucrats of abusing the system, especially if the material sought is remotely embarrassing or controversial", wrote investigative journalist Amanda Cropp.5 "It is ridiculously easy to circumvent the act and to hide information from requesters and Ombudsmen alike", wrote former MP Michael Laws recently: "Of course, all potentially embarrassing information is routinely refused and time delays are simply de rigueur."6 1 Hon J K McLay (23 July 1981) 439 NZPD 1908. 2 Official Information Act 1982, s 4 and long title. Note that the Act also aims "to protect official information to the extent consistent with the public interest and the preservation of personal privacy": Official Information Act 1982, s 4(c) and long title. 3 Official Secrets Act 1951, s 6. -

The New Zealand Connection

Chapter Eleven: The New Zealand Connection Professor Bob Catley A few weeks ago I sat ruminating with a very influential New Zealander. He mused that the Romans had controlled Britain for 400 years but that, when they left, within a short time little was left of them, other than ruins. This may be a parable applicable to New Zealand.1 The British abandoned New Zealand to its fate and joined the European Union in 1973. It is now rapidly becoming a Pacific country. In itself, this may be no bad thing. But the accompanying characteristics include: 〈 Its per capita income is now slipping quickly out of the high income or First World category, and stood in May, 2001 at $US11,200, when the World Bank cut-off point is around $US10,000. It has dropped from $US13,700 in 1999; 〈 Its demographic structure is increasingly non-European and Third World in origin and, despite having recently been the most British of Her Majesty’s Dominions, it may have a bare European majority within a generation; New Zealanders – mostly European – left at the rate of over two per cent a year (79,000) in May, 2000-01 and will not now naturally replace themselves; 〈 It has little control over its major institutions: its banking, other finance, media, energy and transportation systems are almost entirely run, and often are run badly, by foreigners; its universities, health system and housing stock decline to Second or Third World standards; and its crime, youth suicide and social dissonance rates rise to developed world record levels; 〈 Its remaining private corporations -

Investigating Commentary on the Fifth Labour-Led Government's Third Way Approach

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Commons@Waikato New Zealand Sociology 32(1) 2017 Page | 51 Investigating commentary on the fifth Labour-led government’s Third Way approach Gemma Piercy, Kate Mackness, Moana Rarere and Brendan Madley Abstract After the 1999 election of a Labour-led coalition government in Aotearoa New Zealand, a raft of policy reforms adopted characteristics of the ‘Third Way’ ideology promoted by Anthony Giddens. We argue, however, that Third Way characteristics were not implemented in Aotearoa New Zealand without attracting criticism. This article reviews academic analysis and wider commentary on the Third Way in Aotearoa New Zealand, much of which particularly focused on social policy reforms made by the Labour-led coalition government (1999-2008). We have used this literature to identify the varied ways in which the Third Way was defined and the extent to which Third Way ideology was considered to have influenced policy and practice the Aotearoa New Zealand context. Our semi-systematic literature review shows that many commentators argued that New Zealand did indeed implement a policy platform consistent with Third Way ideological characteristics but these were also adapted to the unique context of Aotearoa New Zealand. We explore in detail two key examples of adaptation discussed in the literature: the Labour-led government’s early focus on reducing inequalities between Māori and non-Māori and on renewing civil society through subsidiarity and a partnership approach. Keywords Third Way; Civil society; Partnership; Giddens; Fifth Labour-led government Introduction The fifth Labour-led coalition government (1999-2008) of Aotearoa New Zealand initiated a wide range of policy reforms which reflected values consistent with ‘Third Way’ ideology. -

Advertising and the Market Orientation of Political Parties Contesting the 1999 and 2002 New Zealand General Election Campaigns

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ADVERTISING AND THE MARKET ORIENTATION OF POLITICAL PARTIES CONTESTING THE 1999 AND 2002 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGNS A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICS AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, PALMERSTON NORTH, NEW ZEALAND. CLAIRE ELIZABETH ROBINSON 2006 i ABSTRACT This thesis proposes an alternative way of establishing a link between market orientation and electoral success, by focusing on market orientation as a message instead of as a management function. Using interpretive textual analysis the thesis examines the advertising messages of the highest polling political parties for evidence of voter orientation and competitor orientation in the 1999 and 2002 New Zealand general election campaigns. Relating manifest market orientation to a number of statistical indicators of electoral success the thesis looks for plausible associations between the visual manifestation of market orientation in political advertisements and parties’ achievement of their party vote goals in the 1999 and 2002 elections. It offers party-focused explanations for electoral outcomes to complement existing voter-centric explanations, and adds another level of scholarly understanding of recent electoral outcomes in New Zealand. While the thesis finds little association between demonstration ofcompetitor orientation in political advertisements and electoral success, it finds a plausible relationship between parties that demonstrated a voter orientation in their political advertisements and goal achievement. -

The Politics of Maori Affairs Policy

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. , I I CLOSING THE GAPS? THE POLITICS OF - MAORI AFFAIRS POLICY A thesis presented in partialfulfi lment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology at Massey University, Albany, New Zealand. Louise Virginia Humpage 2002 iii ABSTRACT In searching for ways to decolonise, indigenous peoples have promoted indigenous models of self-determination. Governments, in response, have attempted to protect state legitimacy through the depoliticisation of indigenous claims. An analysis of 'Closing the Gaps', a policy strategy introduced by the Labour-Alliance government in June 2000, illustrates that this has certainly been the case in Aotearoa New Zealand. The policy strategy provides an entry point into exploring the conceptual tensions contained within government policy for Maori, the indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand. Based on an analysis of government documents and interview data, the thesis focuses on three main initiatives incorporated under the 'Closing the Gaps' umbrella. Each initiative highlights a number of bureaucratic, political and conceptual factors that explain why the strategy failed to match political rhetoric. The thesis argues that, in its eagerness to demonstrate a 'commitment' to Maori, the Labour-Alliance government neglected to distinguish between two different socio political projects. The first, 'social inclusion' for all disadvantaged peoples, was framed by a broader 'social development' approach whose ultimate goal was 'national cohesion'. -

Briefing to the Incoming Minister of Health Hon Andrew Little

DECEMBER 2020 BRIEFING TO THE INCOMING MINISTER OF HEALTH HON ANDREW LITTLE Hon Peeni Henare Associate Minister of Health - Māori Health Hon Ayesha Verrall Associate Minister of Health Hon Aupito William Sio Associate Minister of Health - Pacific Peoples Hon Damien O’Connor Minister for Rural Communities Hon Chris Hipkins Minister Covid-19 Response Hon Carmel Sepuloni Minister for ACC FOREWORD An introduction to the Rural Health Networks: NZ Rural General Practice Network, NZ Rural Hospital Network, Students of Rural Health Aotearoa, Rural Nurses NZ, Rural Health Alliance Aotearoa NZ. Tenā koe Ministers Congratulations on your new portfolios. We look forward to working with you to help shape a brighter future for the health and wellbeing of rural communities in New Zealand. We want to be frank with you, rural health in New Zealand is in crisis. The workforce is depleted, stressed and concerned about their ability to sustain the level of support their communities need. The funding formulas for rural health are woefully outdated, including provisions for afterhours and remote rural emergency responses. This situation is exacerbated by the lack of availability of broadband in rural areas that restricts access to many technological advances in effective health provision. There are not enough rural health professionals being trained to fill the current gaps in health provision, let alone forecasts of significant growth in demand. There is also a dearth of empirical data to measure the inequitable health outcomes in rural communities compared to urban centres. Without this data, and the ability to reliably update it, there is no clear way to establish targets and hold health authorities to account. -

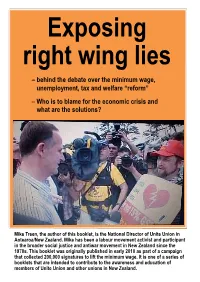

Exposing Right Wing Lies on the Minimum Wage

! ! ! ! ! Exposing ! ! ! ! ! right wing lies ! ! – behind the debate over the minimum wage, ! unemployment, tax and welfare “reform” ! ! – Who is to blame for the economic crisis and ! ! what are the solutions? ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mike Treen, the author of this booklet, is the National Director of Unite Union in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Mike has been a labour movement activist and participant in the broader social justice and antiwar movement in New Zealand since the 1970s. This booklet was originally published in early 2010 as part of a campaign that collected 200,000 signatures to lift the minimum wage. It is one of a series of booklets that are intended to contribute to the awareness and education of members of Unite Union and other unions in New Zealand. Mike Treen speaking to Union protests against proposed “right to sack” laws During the petition campaign on lifting the minimum wage we got asked lots of questions on what the impact this will have on the economy. Will it cause prices to rise? What about its effect on employment? The government has also tried to shift the blame for the growth in unemployment and beneficiary numbers on the unemployed themselves. This was a pattern all governments followed during the last deep recession in New Zealand during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The most recent budget continued the process of shifting taxation from the rich to the poor with the claim it will lead to economic growth and ultimately improve the lives of everyone. Is there any truth behind the government claims? A number of these questions are taken up in the following article in a “Question and Answer” format by Mike Treen, National Director of Unite Union. -

Changing Skills for a Changing World: Recommendations for Adult Literacy Policy in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Occasional Paper Series. INSTITUTION New Zealand Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 219 CE 082 155 AUTHOR Johnson, Alice H. TITLE Changing Skills for a Changing World: Recommendations for Adult Literacy Policy in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Occasional Paper Series. INSTITUTION New Zealand Dept. of Labour, Wellington. REPORT NO OP-2000/2 ISSN ISSN-1173-8782 PUB DATE 2000-10-00 NOTE 116p.; Sponsored by the Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy. Support also provided by Skill New Zealand and the Industry Training Federation. Produced by the Labour Market Policy Group. AVAILABLE FROM Labour Market Policy Group, New Zealand Department of Labour, P.O. Box 3705, Wellington, New Zealand ($10 New Zealand) .For full text: http://lmpg.govt.nz/opapers.htm#OP002. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Basic Skills; Case Studies; Competency Based Education; Developed Nations; *Educational Benefits; Educational Change; Educational History; Foreign Countries; *Learning Motivation; *Literacy Education; National Programs; Program Implementation; Reading Skills; *Workplace Literacy IDENTIFIERS *New Zealand ABSTRACT This report summarizes issues facing New Zealand's modern adult literacy movement and places it in the context of the rapidly changing skill demands of the 21st century. Part I introduces political, economic, and social issues facing New Zealand. Chapter 1 provides an overview of the issues and structures that create the current climate. Part II provides a history of adult literacy in New Zealand. Chapter 2 defines literacy for the 21st century; identifies how literate New Zealanders are, and considers literacy needs by industry. Chapter 3 provides a brief history of New Zealand's literacy movement, describes emergence of workplace literacy, and discusses theoretical underpinnings Freirean and competency-based models. -

PMA to CERD, May 07

Peace Movement Aotearoa PO Box 9314, Wellington 6141, Aotearoa New Zealand. Tel + 64 4 382 8129, fax + 64 4 382 8173, email [email protected] web http://www.converge.org.nz/pma ________________________________________________________________________________ NGO Report to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination With regard to the New Zealand government's Consolidated Periodic Report under Article 9 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1 Introduction 1. Peace Movement Aotearoa is the national networking peace organisation in Aotearoa New Zealand. We are a Pakeha (non-indigenous) organisation, and our membership and networks mainly comprise Pakeha organisations and individuals. 2. As the realisation of human rights is integral to the creation and maintenance of peaceful societies, promoting respect for them is a key aspect of our work. In the context of Aotearoa New Zealand, our main focus in this regard is on support for indigenous peoples' rights - in part as a matter of basic justice, as the rights of indigenous peoples are particularly vulnerable where they are outnumbered by a majority and often ill-informed non-indigenous population as in Aotearoa New Zealand, and because this is a crucial area where the performance of successive governments has been, and continues to be, particularly flawed. 3. There has been a persistent pattern of government actions, policies and practices which discriminate against Maori, historically and in the present day. Underlying these has been the denial of the inherent and inalienable right of self-determination - of the self- determination that was exercised by Maori prior to the arrival of non-Maori; which was proclaimed internationally in the 1835 Declaration of Independence; the continuance of which was guaranteed in the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi (the Treaty); and, in more recent years, was confirmed as a right for all peoples in the international human rights covenants. -

Publ 202/Pols 235 Institutions and the Policy Process

School of Government PUBL 202/POLS 235 INSTITUTIONS AND THE POLICY PROCESS Trimester 2, 2013 COURSE OUTLINE Names and Contact Details Course Coordinator: Dr John Wilson Phone: (04) 817 9358 (Parliament) Email: [email protected] [email protected] Administrator: Robyn McCallum Room: Rutherford House Level 8, Room 821, Pipitea Campus Phone: (04) 463 5458 Email: [email protected] Trimester Dates Teaching Period: Monday 15 July – Friday 18 October Mid-trimester Break: Monday 26 August to Sunday 8 September Study Period: Monday 21st October – Thursday 24 October Examination Period: Friday 25 October – Saturday 16 November (inclusive) 1 Withdrawal from Course 1. Your fees will be refunded if you withdraw from this course on or before Friday 26 July, 2013. 2. The standard last date for withdrawal from this course is Friday 27 September. After this date, students forced to withdraw by circumstances beyond their control must apply for permission on an ‘Application for Associate Dean’s Permission to Withdraw Late’ including supporting documentation. The application form is available from either of the Faculty’s Student Customer Service Desks. Class Times and Room Numbers Lectures: (Kelburn campus) Tutorials: (Kelburn campus) Monday 1.10 – 2.00pm, HU LT220 Monday, 12.00 – 12.50pm, MY103 Wednesday 1.10 – 2.00pm, HU LT220 Monday, 2.10 – 3.00pm, MY404 Wednesday, 12.00 – 12.50pm, MY301 Wednesday, 2.10 – 3.00pm, VZ103 Course Delivery The course will be delivered through two 50-minute lectures and one 50-minute tutorial per week. The tutorials are based on the lecture material and set readings. -

The Demographic and Political Imperatives for Improving Crown-Maori Relations in Aotearoa-New Zealand

The Demographic and Political Imperatives for Improving Crown-Maori Relations in Aotearoa-New Zealand HARRY A. KERSEY, JR. AsiaPacific ISSUES Analysis from the East-West Center SUMMARY Nearly a decade has passed since the United Nations declared No. 64 November 2002 International Year of the World’s Indigenous People. Yet issues of social and The U.S. Congress established the East-West Center in 1960 to economic marginalization, inequality, cultural survival, and change related to foster mutual understanding and cooperation among the govern- indigenous peoples continue to challenge the global community. In Aotearoa- ments and peoples of the Asia Pacific region, including the United New Zealand the Pakeha (Caucasian) settler population for many decades States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government dominated the political landscape, leaving little voice for the nation’s indige- with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, nous Maori people struggling for greater rights. Today, however, the growing corporations, and Asian and Pacific governments. Maori population makes New Zealand the only First World country in which The AsiaPacific Issues series contributes to the Center’s role as the indigenous people’s movement for self-determination is sufficiently large a neutral forum for discussion of i issues of regional concern. The to promise the possibility of major societal transformations. Over the past views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those quarter century, regardless of which political party or coalition held power, of the Center. escalating Maori demographic trends and increased political activism have encouraged the Crown to address Maori concerns and grievances.ii Today, with one out of four children under the age of five a Maori, the government has little option but to negotiate with a growing indigenous community.