Managing Our Nation's Fisheries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Static Fishing Around Fish Aggregating Devices (Fads) and Offshore Banks

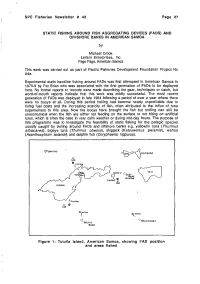

SPC Fisheries Newsletter # 42 Page 27 STATIC FISHING AROUND FISH AGGREGATING DEVICES (FADS) AMD OFFSHORE BANKS IN AMERICAN SAMOA by Michael Crook Leilani Enterprises, Inc Pago Pago, American Samoa This work was carried out as part of Pacific Fisheries Development Foundation Project No 44a. Experimental static handline fishing around FADs was first attempted in American Samoa in 1978-9 by Pat Brian who was associated with the first generation of FADs to be deployed here. No formal reports or records were made describing the gear, techniques or catch, but word-of-mouth reports indicate that this work was mildly successful. The most recent generation of FADs was deployed in late 1984 following a period of over a year where there were no buoys at all. During this period trolling had become nearly unprofitable due to rising fuel costs and the increasing scarcity of fish, often attributed to the influx of tuna superseiners to this area. Now the buoys have brought the fish but trolling can stiil be uneconomical when the fish are either not feeding on the surface or not biting on artificial lures, which is often the case in very calm weather or during mid-day hours. The purpose of this programme was to investigate the feasibility of static fishing for the pelagic species usually caught by trolling around FADs and offshore banks e.g. yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), skipjack {Katsuwonus pelamis), wahoo (Acanthocybium solandn) and dolphin fish (Coryphaena hippurus). (P SWAINS a lORl^C VOLOSEGA 'E' FAD n 3 miles TA U /-'^Paao sJ AUNU'U V C~?ago| ^o BANK \ , \_^J 20 miles \ / 5 miles" ^ FAD y TUTUILA w^-> ( 3 miles [ 'c' 0 FAD 35 miles 40 miles "SOUTHEAST " SOUTH BANK Figure 1: Tutuila Island, American Samoa, showing FAD position and areas fished PSger?28! SPCi FisherJesrvWews letters #42; Mettibds (arM ;:inaterialsn Oi'NTASSflSDA n&''~\ mtU^/i Slli'^m-i orh"-t The sixteen trips made between December 1984 and April 1985 were aboard the 40 ft. -

Combined!Effects!In!Europe's!Seas!

OCP/EEA/NSS/18/002.ETC/ICM!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!ETC/ICM!Technical!Report!4/2019! Multiple!pressures!and!their! combined!effects!in!Europe’s!seas! Prepared!by!/!compiled!by:!! Samuli!Korpinen,!Katja!Klančnik! Authors:!! Samuli Korpinen & Katja Klančnik (editors), Monika Peterlin, Marco Nurmi, Leena Laamanen, Gašper Zupančič, Ciarán Murray, Therese Harvey, Jesper H Andersen, Argyro Zenetos, Ulf Stein, Leonardo Tunesi, Katrina Abhold, GerJan Piet, Emilie Kallenbach, Sabrina Agnesi, Bas Bolman, David Vaughan, Johnny Reker & Eva Royo Gelabert ETC/ICM'Consortium'Partners:'' Helmholtz!Centre!for!Environmental!Research!(UFZ),!Fundación!AZTI,!Czech!Environmental! Information!Agency!(CENIA),!Ioannis!Zacharof&!Associates!Llp!Hydromon!Consulting! Engineers!(CoHI(Hydromon)),!Stichting!Deltares,!Ecologic!Institute,!International!Council!for! the!Exploration!of!the!Sea!(ICES),!Italian!National!Institute!for!Environmental!Protection!and! Research!(ISPRA),!Joint!Nature!Conservation!Committee!Support!Co!(JNCC),!Middle!East! Technical!University!(METU),!Norsk!Institutt!for!Vannforskning!(NIVA),!Finnish!Environment! Institute!(SYKE),!Thematic!Center!for!Water!Research,!Studies!and!Projects!development!! (TC!Vode),!Federal!Environment!Agency!(UBA),!University!Duisburg.Essen!(UDE)! ! ! ! Cover'photo! ©!Tihomir!Makovec,!Marine!biology!station!Piran,!Slovenia! ' Layout! F&U!confirm,!Leipzig! ! Legal'notice' The!contents!of!this!publication!do!not!necessarily!reflect!the!official!opinions!of!the!European!Commission!or!other!institutions! -

Fishing Techniques Used Around Fish Aggregation Devices in French Polynesia

SPC/Fisheries 22/WP.14 27 July 1990 ORIGINAL : FRENCH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION TWENTY-SECOND REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia 6-10 August, 1990) FISHING TECHNIQUES USED AROUND FISH AGGREGATION DEVICES IN FRENCH POLYNESIA by F. Leproux, G. Moarii, S. Yen EVAAM, B.P. 20, Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia 643/90 SPC/Fisheries 22/WP.14 Page 1 FISHING TECHNIQUES USED AROUND FISH AGGREGATION DEVICES IN FRENCH POLYNESIA Mooring FADs in French Polynesian waters, which began in June 1981, has had a favourable impact on local fishermen who, although they were sceptical to begin with, have come to use this assistance increasingly, many of them finding it very helpful. The techniques of fishing around FADs have changed over the years and in 1990 four are still currently in use, while new techniques are constantly being developed and taught in order to obtain better yields. 1. FISHING TECHNIQUES 1.1 Handline fishing Many small boats (3 to 6m) do deep fishing near FADs when a school of tuna is present. The handline is made of nylon line of 130 kg and a tuna hook (cf Diagram no. 1, Plate no. 1). The bait used varies with the season: thus "operu" (Decapterus macarellus), "ature" (Selar crumennhialmus), "numa" (Mulloidichihys samoensis), "marara" (Cysselurus simus), and skipjack fillet (Katsuwonus pelamis) are the most commonly used. The technique consists in placing this bait low down in the school. In order to facilitate the drop of the line, a stone is fixed to it temporarily. When the fisherman considers that he has reached the required depth, he gives the line a sharp jerk upwards which releases the stone and also some crumbs which awake the tunas' appetite. -

Translation Series No.1375

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Translation Series No. 1375 Bioebenoses and biomass of benthos of the Newfoundland-Labrador region. By Ki1N. Nesis Original title: Biotsenozy i biomassa bentosa N'yufaund- • .lendskogo-Labradorskogo raiona.. From: Trudy Vsesoyuznogo Nauchno-Issledovatel'skogo •Instituta Morskogo Rybnogo Khozyaistva Okeanografii (eNIRO), 57: 453-489, 1965. Translated by the Translation Bureau(AM) Foreign Languages Division Department of the Secretary of State of Canada Fisheries Research Board of Canada • Biological Station , st. John's, Nfld 1970 75 pages typescript 'r OEPARTMENT OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE SECRÉTARIAT D'ÉTAT TRANSLATION BUREAU BUREAU DES TRADUCTIONS FOREIGN LANGUAGES DIVISION DES LANGUES DIVISION ° CANADA ÉTRANGÈRES TRANSLATED FROM - TR,ADUCTION DE INTO - EN Russian English 'AUTHOR - AUTEUR Nesis K.N. TITLE IN ENGLISH - TITRE ; ANGLAIS Biocoenoses and biomas of benthos of the Newfolindland-Labradoriregion Title . in foreign_iangnage---(tranalitarate_foreisn -ottantatere) Biotsenozy i biomassa bentosa N i yufaundlendSkogo-Labradorskogoraiona. , .ReF5RENCE IN FOREIGN ANGUA2E (NAME OF BOOK OR PUBLICATION) IN FULL. TRANSLITERATE FOREIGN CFiA,IRACTERS. • REFERENCE' EN LANGUE ETRANGERE (NOM DU LIVRE OU PUBLICATION), AU COMPLET. TRANSCRIRE EN CARACTERES PHONETIQUEL •. Trudylesesoyuznogo nauchno-iàsledovaterskogo instituta morskogo — rybnogo khozyaistva i okeanogràfii - :REFEREN CE IN ENGLISH - RÉFÉRENCE EN ANGLAIS • Trudy of the 40.1-Union Scientific-Research Instituteof Marine . Fiseriés and Oceanography. PUBLISH ER ÉDITEUR PAGE,NUMBERS IN ORIGINAL DATE OF PUBLICATION NUMEROS DES PAGES DANS DATE DE PUBLICATION . L'ORIGINAL YE.tR ISSUE.NO . 36 VOLUME ANNEE NUMERO PLACE OF PUBLICATION NUMBER OF TYPED PAGES LIEU DE PUBLICATION NOMBRE DE PAG.ES DACTY LOGRAPHIEES 1965 5 7 REQUEr IN G• DEPA RTMENT Fisheries Research Board TRANSLATION BUREAU NO. -

Multiple!Pressures!And!Their! Combined!Effects!In!Europe's!Seas!

OCP/EEA/NSS/18/002.ETC/ICM!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!ETC/ICM!Technical!Report!4/2019! Multiple!pressures!and!their! combined!effects!in!Europe’s!seas! Prepared!by!/!compiled!by:!! Samuli!Korpinen,!Katja!Klančnik! Authors:!! Monika Peterlin, Marco Nurmi, Leena Laamanen, Gašper Zupančič, Andreja Popit, Ciarán Murray, Therese Harvey, Jesper H Andersen, Argyro Zenetos, Ulf Stein, Leonardo Tunesi, Katrina Abhold, GerJan Piet, Emilie Kallenbach, Sabrina Agnesi, Bas Bolman, David Vaughan, Johnny Reker & Eva Royo Gelabert ETC/ICM'Consortium'Partners:'' Helmholtz!Centre!for!Environmental!Research!(UFZ),!Fundación!AZTI,!Czech!Environmental! Information!Agency!(CENIA),!Ioannis!Zacharof&!Associates!Llp!Hydromon!Consulting! Engineers!(CoHI(Hydromon)),!Stichting!Deltares,!Ecologic!Institute,!International!Council!for! the!Exploration!of!the!Sea!(ICES),!Italian!National!Institute!for!Environmental!Protection!and! Research!(ISPRA),!Joint!Nature!Conservation!Committee!Support!Co!(JNCC),!Middle!East! Technical!University!(METU),!Norsk!Institutt!for!Vannforskning!(NIVA),!Finnish!Environment! Institute!(SYKE),!Thematic!Center!for!Water!Research,!Studies!and!Projects!development!! (TC!Vode),!Federal!Environment!Agency!(UBA),!University!Duisburg.Essen!(UDE)! ! ! ! Cover'photo! ©!Tihomir!Makovec,!Marine!biology!station!Piran,!Slovenia! ' Layout! F&U!confirm,!Leipzig! ! Legal'notice' The!contents!of!this!publication!do!not!necessarily!reflect!the!official!opinions!of!the!European!Commission!or!other!institutions! of!the!European!Union.!Neither!the!European!Environment!Agency,!the!European!Topic!Centre!on!Inland,!Coastal!and!Marine! -

Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission

32nd Annual Report of the PACIFIC MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION FOR THE YEAR 1979 TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES AND TO THE GOVERNORS AND LEGISLATURES OF WASHINGTON, OREGON, CALIFORNIA, IDAHO, AND ALASKA Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission 528 S.W. Mill Street Portland, Oregon 97201 July 8, 1980 32nd Annual Report of the PACIFIC MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION FOR THE YEAR 1979 PREFACE The Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission was created in 1947 with the consent of Congress. The Commission serves five member States: Alaska, California, Idaho, Oregon and Washington. The purpose of this Compact, as stated in its Goal and Objectives, is to promote the wise management, utilization, and development of fisheries of mutual concern, and to develop a joint program of protection, enhancement, and prevention of physical waste of such fisheries. The advent of the Fishery Conservation and Management Act {FCMA) of 1976 and amendments thereto has caused spectacular and continuing changes in the management of marine fisheries in the United States. The FCMA created the Fishery Conservation Zone (FCZ) between 3 and 200 nautical miles offshore, established 8 Regional Fishery Management Councils with authority to develop fishery management plans within the FCZ, and granted the Secretary of Commerce the power to regulate both domestic and foreign fishing fleets within the FCZ. The FCMA greatly modified fishery management roles at state, interstate, national and international levels. The Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission recognized early that its operational role would change as a result of possible functional overlaps with the two regional fishery management councils established on the Pacific Coast. On the one hand, the FCMA provides non-voting Council membership to the Executive Directors of the interstate Marine Fisheries Commissions, thus assuring active participation as the Councils deliberate on fishery matters of concern to the States. -

Recommendations for Recreational Fisheries Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5

PHAROS4MPAS SAFEGUARDING MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN THE GROWING MEDITERRANEAN BLUE ECONOMY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RECREATIONAL FISHERIES CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 PART ONE BACKGROUND INFORMATION: RECREATIONAL FISHERIES 7 Front cover: Catching a greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili) 1.1. Definition of recreational fisheries in the Mediterranean 9 from a big game fishing boat © Bulentevren / Shutterstock 1.2. Importance of recreational fisheries in Europe and the Mediterranean 10 1.3. The complexity of recreational fisheries in the Mediterranean 13 Publication We would like to warmly thank all the people and organizations who were part of the advisory group of Published in July 2019 by PHAROS4MPAs. this publication or kindly contributed in some other PART TWO © PHAROS4MPAs. All rights reserved way: Fabio Grati (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche - ISMAR), Reproduction of this publication for educational or other Antigoni Foutsi, Panagiota Maragou and Michalis Margaritis RECREATIONAL FISHERIES: INTERACTIONS WITH MARINE PROTECTED AREAS 15 non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written (WWF-Greece), Victoria Riera (Generalitat de Catalunya), Marta permission from the copyright holder provided the source is Cavallé (Life Platform), Jan Kappel (European Anglers Alliance), PART THREE fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale Anthony Mastitski (University of Miami), Sylvain Petit (PAP/ or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written RAC), Robert Turk (Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Nature BENEFITS AND IMPACTS OF RECREATIONAL FISHERIES 21 permission of the copyright holder. Conservation), Paco Melia (Politechnica Milano), Souha El Asmi and Saba Guellouz (SPA/RAC), Davide Strangis and Lise Guennal 3.1. Social benefits and impacts 22 Citation of this report: Gómez, S., Carreño, A., Sánchez, (CRPM), Marie Romani, Susan Gallon and Wissem Seddik E., Martínez, E., Lloret, J. -

Seafood Group Project Final Report

University of California, Santa Barbara Bren School of Environmental Science and Management From Sea to Table: Recommendations for Tracing Seafood 2010 Group Project Jamie Gibbon Connor Hastings Tucker Hirsch Kristen Hislop Eric Stevens Faculty Advisors: Hunter Lenihan John Melack Client: Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Sustainable Seafood Initiative From Sea to Table: Recommendations for Tracing Seafood From Sea to Table: Recommendations for Tracing Seafood As authors of this Group Project report, we are proud to archive this report on the Bren School’s website such that the results of our research are available for all to read. Our signatures on the document signify our joint responsibility to fulfill the archiving standards set by the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. Jamie Gibbon Connor Hastings Tucker Hirsch Kristen Hislop Eric Stevens The mission of the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management is to produce professionals with unrivaled training in environmental science and management who will devote their unique skills to the diagnosis, assessment, mitigation, prevention, and remedy of the environmental problems of today and the future. A guiding principal of the School is that the analysis of environmental problems requires quantitative training in more than one discipline and an awareness of the physical, biological, social, political, and economic consequences that arise from scientific or technological decisions. The Group Project is required of all students in the Master’s of Environmental Science and Management (MESM) Program. It is a three-quarter activity in which small groups of students conduct focused, interdisciplinary research on the scientific, management, and policy dimensions of a specific environmental issue. -

Why International Catch Shares Won't Save Ocean Biodiversity

Michigan Journal of Environmental & Administrative Law Volume 2 Issue 2 2013 Why International Catch Shares Won't Save Ocean Biodiversity Holly Doremus University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjeal Part of the Environmental Law Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, and the Natural Resources Law Commons Recommended Citation Holly Doremus, Why International Catch Shares Won't Save Ocean Biodiversity, 2 MICH. J. ENVTL. & ADMIN. L. 385 (2013). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjeal/vol2/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Environmental & Administrative Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Doremus_Final_Web_Ready_FINAL_12May2013 7/18/2013 4:24 PM WHY INTERNATIONAL CATCH SHARES WON’T SAVE OCEAN BIODIVERSITY Holly Doremus* Skepticism about the efficacy and efficiency of regulatory approaches has produced a wave of enthusiasm for market-based strategies for dealing with environmental conflicts. In the fisheries context, the most prominent of these strategies is the use of “catch shares,” which assign specific proportions of the total allowable catch to individuals who are then free to trade them with others. Catch shares are now in wide use domestically within many nations, and there are increasing calls for implementation of internationally tradable catch shares. Based on a review of theory, empirical evidence, and two contexts in which catch shares have been proposed, this Article explains why international catch shares are not likely to arrest the decline of ocean biodiversity. -

DYNAMIC HABITAT USE of ALBACORE and THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES in the CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM Calcofi Rep., Vol

MUHLING ET AL.: DYNAMIC HABITAT USE OF ALBACORE AND THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES IN THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM CalCOFI Rep., Vol. 60, 2019 DYNAMIC HABITAT USE OF ALBACORE AND THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES IN THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM BARBARA MUHLING, STEPHANIE BRODIE, MICHAEL JACOX OWYN SNODGRASS, DESIREE TOMMASI NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory University of California, Santa Cruz Boulder, CO Institute for Marine Science Santa Cruz, CA CHRISTOPHER A. EDWARDS ph: (858) 546-7197 Ocean Sciences Department [email protected] University of California, Santa Cruz, CA BARBARA MUHLING, OWYN SNODGRASS, YI XU HEIDI DEWAR, DESIREE TOMMASI, JOHN CHILDERS Department of Fisheries and Oceans NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center Delta, British Columbia, Canada San Diego, CA STEPHANIE SNYDER STEPHANIE BRODIE, MICHAEL JACOX Thomas More University, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center Crestview Hills, KY Monterey, CA ABSTRACT peiods, krill, and some cephalopods (Smith et al. 2011). Juvenile north Pacific albacore Thunnus( alalunga) for- Many of these forage species are fished commercially, age in the California Current System (CCS), supporting but also support higher-order predators further up the fisheries between Baja California and British Columbia. food chain, such as other exploited species (e.g., tunas, Within the CCS, their distribution, abundance, and for- billfish) and protected resources (e.g., marine mammals aging behaviors are strongly variable interannually. Here, and seabirds) (Pikitch et al. 2004; Link and Browman we use catch logbook data and trawl survey records to 2014). Effectively managing marine ecosystems to pre- investigate how juvenile albacore in the CCS use their serve these trophic linkages, and improve robustness of oceanographic environment, and how their distributions management strategies to environmental variability, thus overlap with the habitats of four key forage species. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

California Sea Lion Interaction and Depredation Rates with the Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Fleet Near San Diego

HANAN ET AL.: SEA LIONS AND COMMERCIAL PASSENGER FISHING VESSELS CalCOFl Rep., Vol. 30,1989 CALIFORNIA SEA LION INTERACTION AND DEPREDATION RATES WITH THE COMMERCIAL PASSENGER FISHING VESSEL FLEET NEAR SAN DIEGO DOYLE A. HANAN, LISA M. JONES ROBERT B. READ California Department of Fish and Game California Department of Fish and Game c/o Southwest Fisheries Center 1350 Front Street, Room 2006 P.O. Box 271 San Diego, California 92101 La Jolla, California 92038 ABSTRACT anchovies, Engraulis movdax, which are thrown California sea lions depredate sport fish caught from the fishing boat to lure surface and mid-depth by anglers aboard commercial passenger fishing fish within casting range. Although depredation be- vessels. During a statewide survey in 1978, San havior has not been observed along the California Diego County was identified as the area with the coast among other marine mammals, it has become highest rates of interaction and depredation by sea a serious problem with sea lions, and is less serious lions. Subsequently, the California Department of with harbor seals. The behavior is generally not Fish and Game began monitoring the rates and con- appreciated by the boat operators or the anglers, ducting research on reducing them. The sea lion even though some crew and anglers encourage it by interaction and depredation rates for San Diego hand-feeding the sea lions. County declined from 1984 to 1988. During depredation, sea lions usually surface some distance from the boat, dive to swim under RESUMEN the boat, take a fish, and then reappear a safe dis- Los leones marinos en California depredan peces tance away to eat the fish, tear it apart, or just throw colectados por pescadores a bordo de embarca- it around on the surface of the water.