US 395 / I-82 to I-182 Corridor Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

Davita OM Brian Mayer.Indd

REPRESENTATIVE PICTURE Actual Site Photo DAVITA EXCLUSIVLY LISTED BY: Brian Mayer RICHLAND, WASHINGTON National Retail Group 206.826.5716 1315 Aaron Drive, Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] DaVita | 1 PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS INVESTMENT GRADE TENANT: 10+ YEAR HISTORICAL OCCUPANCY: Nation’s leading provider of kidney dialysis Build to Suit for DaVita in 2008, the Tenant services and a Fortune 500 company, has occupied the property for over 10 DaVita generated $10.88 Billion in net years. revenue in 2017. S&P Investment Grade Rating of BB. EARLY LEASE EXTENSION: MINIMAL LANDLORD RESPONSIBILITIES: In December 2018, DaVita exercised its Tenant is responsible for taxes, insurance first 5-year option, as well as exercising its and CAM’s. Landlord is responsible for roof, second 5-year option early, for a combined structure and limited capital expenditures. 10-year renewal period. SIGNIFICANT TENANT CAPITAL EXPENDITURES: MANAGEMENT FEE REIMBURSEMENT: Tenant contributed approximately $1.5 Lease allows Landlord to collect a million towards its build-out in 2008, and is management fee as additional rent. A slated to contribute an additional $250,000 management fee equal to 6% of base rent in 2019. is currently being collected. HIGHWAY VISIBILITY & ACCESS: PROXIMITY TO MAJOR MEDICAL CAMPUS: Features easy access and excellent visibility In close proximity to the Tri-Cities major from Interstate 182 (69,000 VPD), Highway medical campus, including Kadlec Regional 240 (46,000 VPD) and George Washington Medical Center, Lourdes Health and Seattle Way (41,000 VPD). Children’s’ Hospital. ANNUAL RENTAL INCREASES: DENSELY POPULATED AFFLUENT AREA: Lease benefits from 2% annual increases Features an average household income of in the initial Lease Term and 2.5% annual $93,558 within 5 miles, and a population increases in the Option Period. -

Transportation Choices 3

Transportation Choices 3 MOVEMENT OF PEOPLE | MOVEMENT OF FREIGHT AND GOODS Introduction Facilities Snapshot This chapter organizes the transportation system into two categories: movement of people, and movement of freight and goods. Movement of people encompasses active transportation, transit, rail, air, and automobiles. Movement of freight and goods encompasses rail, marine cargo, air, vehicles, and pipelines. 3 Three Airports: one commercial, two Community Consistent with federal legislation (23 CFR 450.306) and Washington State Legislation (RCW 47.80.030), the regional transportation system includes: 23 Twenty-three Fixed Transit Routes ▶All state-owned transportation facilities and services (highways, park-and-ride lots, etc); 54 Fifty-Four Miles of Multi-Use Trails ▶All local principal arterials and selected minor arterials the RTPO considers necessary to the plan; 2.1 Multi- ▶Any other transportation facilities and services, existing and Two Vehicles per Household* proposed, including airports, transit facilities and services, roadways, Modal rail facilities, marine transportation facilities, pedestrian/bicycle Transport facilities, etc., that the RTPO considers necessary to complete the 5 regional plan; and Five Rail Lines System ▶Any transportation facility or service that fulfills a regional need or impacts places in the plan, as determined by the RTPO. 4 Four Ports *Source: US Census Bureau, 2014 ACS 5-year estimates. Chapter 3 | Transportation Choices 39 Figure 3-1: JourneyMode to ChoiceWork -ModeJourney Choice to Work in the RTPO, 2014 Movement of People Walk/ Bike, Public Transit, 2.2% Other, 4.3% People commute for a variety of reasons, and likewise, a variety of 1.2% ways. This section includes active transportation, transit, passenger Carpooled, 12.6% rail, passenger air, and passenger vehicles. -

Northwest Area Fire Weather Annual Operating Plan

Williams Flats Fire: August 7, 2019 Photo: Inciweb 2021 Northwest Area Fire Weather Annual Operating Plan 1 This page intentionally left blank 2 3 This page intentionally left blank 4 Table of Contents Agency Signatures/Effective Dates of the AOP ......................................................................................3 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................6 NWS Services and Responsibilities.........................................................................................................8 Wildland Fire Agency Services and Responsibilities ........................................................................... 14 Joint Responsibilities ...........................................................................................................................15 NWCC Predictive Services ...................................................................................................................17 Boise .................................................................................................................................................. 25 Medford...............................................................................................................................................30 Pendleton ........................................................................................................................................... 41 Portland...............................................................................................................................................53 -

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-1 Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-2 Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project September 2013 Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 | T.Y. Lin International | Safdie Rabines Architects | Estrada Land Planning Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 4050 Taylor Street San Diego, CA 92110 T.Y. Lin International 404 Camino del Rio South, Suite 700 San Diego, CA 92108 | 619.692.1920 Safdie Rabines Architects 925 Ft. Stockton Drive San Diego, CA 92123 | 619.297.6153 Estrada Land Planning 755 Broadway Circle, Suite 300 San Diego, CA 92101 | 619.236.0143 Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Table of Contents Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Table of Contents I. Project Background D. Design Themes....................17 vi. Typical Freeway Undercrossing. 36 vii. Typical Bridge Details. 37 A. Introduction....................1 i. Corridor Theme Elements. 17 ii. Corridor Theme Priorities. 19 - Southern Bluff Theme....................38 B. Purpose.......................1 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................39 iii. Corridor Theme Units. 20 C. Components & Products. 1 - Northern Urban Theme. 40 - Southern Bluff Theme....................21 D. The Proposed Project. 2 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................22 B. Walls.............................41 E. Previous Relevant Documents. 3 - Northern Urban Theme. 23 i. Theme Unit Specific Wall Concepts. -

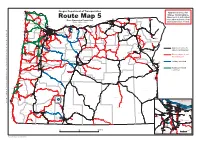

Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ

ASTORIA Oregon Department of Transportation Warrenton H104 Svensen Approved routes for Mayger 30 Westport ¤£ Clatskanie Æ 101 Olney Ä Rainier ¤£ H105 Triples Combinations. Æ Gearhart C L A T S O PÄ 47 Prescott SEASIDE Goble H332 202 Mist 73300 Movement is authorized 395 Umapine Necanicum Cold ¤£2 Jewell ¤£ Springs Jct. C O L U M B I A Æ Ä MP 9.76 Umatilla Jct. Milton-Freewater Flora Ä Æ Æ Cannon Beach Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ H103 Pittsburg Irrigon Ä only under authority of an Columbia City Æ Over-Dimension Permit Unit Ä Elsie 47 730 Holdman 53 ST. HELENS ¤£ Helix 11 Vernonia Boardman 0 207 26 7 30 82 Athena Æ ¤£ Ä Over-Dimension Permit. ¤£ Revised March 2020 HERMISTON 3 ¨¦§ H Heppner Jct. Æ Ä H334 Weston Scappoose Stanfield 3 Nehalem 3 Adams 204 Manzanita HOOD Permission not granted to 5 RIVER cross RR crossing at MP 102.40 30 37 Æ 84 30 Echo Ä Wheeler Buxton £ in Hood River 84 ¤£ Arlington H W A L L O W A ¤ 3 Cascade ¨¦§ Biggs § MP 13.22 ¨¦ 26 Locks Jct. Rufus 3 Æ Rockaway Celilo Blalock Ä H320 1 Æ T I L L A M O O K ¤£ Mosier Ä 82 Beach Banks North H281 PENDLETON Plains PORTLAND Æ Ä Minam Imnaha Odell Wallowa Æ Ä 74 Garibaldi Wasco 207 W A S H I N G T O N The Elgin . Bay City Troutdale Multnomah Æ CorneliusÄ Fairview Dalles t Forest HILLSBORO H O O D H282 206 i 6 Grove Falls G I L L I A M Wood 84 Oceanside Beaverton R I V E R U M A T I L L A Summerville m H131 Village Ione r 8 ¨¦§ Lostine Æ Parkdale 197 Ä Gresham Moro 0 e Tillamook M U L T N O M A H MP 83.00 ¤£ 30 Imbler 5 Netarts ENTERPRISE Æ Ä Pilot 3 Æ Ä £ Æ Ä ¤ p Æ Ä Rock H Gaston Tigard -

Last Link of I-90 Ends 30-Year Saga by Peggy Reynolds, Seattle Times, 9 Sept 1993

Last Link Of I-90 Ends 30-Year Saga By Peggy Reynolds, Seattle Times, 9 Sept 1993 Erica Clibborn's red convertible will be one of the first cars Sunday across the new Lacey V. Murrow Floating Bridge, last link in a project that started before Erica was born. The University of Washington junior, who will be going home to Mercer Island for Sunday dinner, was born in 1973, the year a federal court sent the Seattle-area stretch of Interstate 90 back to square one. By then, I-90 already reached most of the 3,063 miles from Boston to south Bellevue, and the final major segment had been in the works for 10 years. It would be another 20 years before that last 7 miles would be finished. That completion will be marked this weekend with an array of public events, and Clibborn and other drivers should be able to go across the eastbound span by 5 p.m. Sunday. That opening means that I-90 survived the anti-government sentiment of the late 1960s, the mass-transit worship of the '70s and the budget cutbacks of the '80s - even while other urban interstate projects were biting the dust in New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington, San Francisco and Portland. Nevertheless, whether or not I-90 was really needed was subject to debate at all levels. It attracted a formidable enemies list, and was rescued regularly by a cast of hundreds. Without any one of its friends in local governments, on the state Transportation Commission, in the Legislature and in Congress, I-90 could have ended in south Bellevue instead of making it to its junction with Interstate 5 in Seattle. -

I-90 Tolling Update

I-90 Tolling Update John White Director of Tolled Corridors Development Paula Hammond Steve Reinmuth Secretary of Transportation Chief of Staff Seattle City Council January 28, 2012 I-90 is part of the Cross-Lake Washington Corridor • Represents two major east-west “Cross- Lake” travel corridors: I-90 and SR 520. • WSDOT is tolling SR 520 as part of a multi- faceted financing strategy to help generate enough revenue to fund replacement of the structurally-vulnerable bridge. • A new 520 bridge will give Cross-Lake WA travelers a safer, more reliable trip. 2 Funding for the SR 520 Program Construction Unfunded Program cost estimate (Oct. 2012): $4.13 billion What’s funded: $2.72 billion (includes sales tax deferral) • Pontoon construction in Grays Harbor. • The floating bridge and landings. • Eastside transit and HOV improvements. • The north half of the west approach bridge. Updated November 2012 Costs and Funding for Replacing SR 520 Bridge SR 520 program cost estimate $4.128 B Funding received to date $2.724 B State and local funding (Nickel and TPA) $0.55 B Federal funding $0.12 B SR 520 Account (tolling and future federal funds) $1.91 B Toll proceeds • TIFIA $300M • Triple pledge bonds $550M • First tier toll $159M • PAYGO $74M Federal proceeds • GARVEE $825M Deferred sales tax $0.14 B Unfunded need $1.404 B Program cost estimate based on 2012 CEVP - updated 10/25/12 4 Early Indicators of 520 Toll Success • Meeting or beating traffic forecasts. • Meeting revenue forecasts. • Most people are paying with Good To Go! accounts. – More than 384,000 active Good To Go! accounts. -

I-15 Corridor System Master Plan Update 2017

CALIFORNIA NEVADA ARIZONA UTAH I-15 CORRIDOR SYSTEM MASTER PLAN UPDATE 2017 MARCH 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The I-15 Corridor System Master Plan (Master Plan) is a commerce, port authorities, departments of aviation, freight product of the hard work and commitment of each of the and passenger rail authorities, freight transportation services, I-15 Mobility Alliance (Alliance) partner organizations and providers of public transportation services, environmental their dedicated staff. and natural resource agencies, and others. Individuals within the four states and beyond are investing Their efforts are a testament of outstanding partnership and their time and resources to keep this economic artery a true spirit of collaboration, without which this Master Plan of the West flowing. The Alliance partners come from could not have succeeded. state and local transportation agencies, local and interstate I-15 MOBILITY ALLIANCE PARTNERS American Magline Group City of Orem Authority Amtrak City of Provo Millard County Arizona Commerce Authority City of Rancho Cucamonga Mohave County Arizona Department of Transportation City of South Salt Lake Mountainland Association of Arizona Game and Fish Department City of St. George Governments Bear River Association of Governments Clark County Department of Aviation National Park Service - Lake Mead National Recreation Area BNSF Railway Clark County Public Works Nellis Air Force Base Box Elder County Community Planners Advisory Nevada Army National Guard Brookings Mountain West Committee on Transportation County -

I-90: Twin Falls (North Bend Vicinity) to I-82 Jct (Ellensburg) Corridor

Corridor Sketch Summary Printed at: 3:54 PM 3/29/2018 WSDOT's Corridor Sketch Initiative is a collaborative planning process with agency partners to identify performance gaps and select high-level strategies to address them on the 304 corridors statewide. This Corridor Sketch Summary acts as an executive summary for one corridor. Please review the User Guide for Corridor Sketch Summaries prior to using information on this corridor: I-90: Twin Falls (North Bend Vicinity) to I-82 Jct (Ellensburg) This 74-mile long northwest-southeast corridor is located in King and Kittitas counties and runs between Twin Falls, just east of North Bend, and the Interstate 82 junction in the city of Ellensburg. The corridor includes a five-mile segment of US Route 97 on the eastern end of the corridor that runs concurrently with I-90. In the upper elevations of western Kittitas County, I-90 passes near Keechelus, Kachess, and Cle Elum lakes, three large reservoirs that provide irrigation water to the Kittitas and Yakima valleys. I-90 follows the Yakima River valley between the Keechelus Lake in the Snoqualmie Pass area and the city of Ellensburg. The corridor is primarily rural with some urban areas in the cities of Cle Elum and Ellensburg. The corridor travels over Snoqualmie Pass through the Cascade Mountains. On the western end of the corridor, the route is on a steep grade through heavily wooded national forest lands before reaching Snoqualmie Pass and Kittitas County. On the eastern section of the corridor, the route descends into grasslands and irrigated fields in the lower Kittitas Valley. -

3.6-1 3.6 Traffic and Circulation Construction of the Wanapa Energy

3.6 Traffic and Circulation Construction of the Wanapa Energy Center would most likely affect traffic flow on McNary Beach Access Road, U.S. Highway 730, and U.S. Highway 395/State Route 32. Up to 600 workers would travel to the facility site during construction, 100 to the natural gas supply/wastewater discharge pipeline routes, and 120 to the transmission line route. During operation, 30 workers would work at the facility. 3.6.1 Affected Environment Major highways accessing the project study area include U.S. Highway 730 (i.e., U.S. Highway 730; the Columbia River Highway), U.S. Highway 395/State Route (SR) 32 (i.e., SR 32; the Umatilla-Stanfield Highway), Interstate 82 (I-82), and State Route 207 (i.e., the Hermiston Highway). U.S. Highway 730 is a 2-lane west-east highway that generally runs along the south side of the Columbia River. U.S. Highway 395/SR 32 is a 2-lane northwest-southeast highway that runs from U.S. Highway 730 in the north; through Umatilla, Hermiston, and Stanfield; and then to I-84/U.S. 30 in the south. I-82 is a 4-lane highway running north-south from the Tri-Cities in Washington until it intersects with I-84/U.S. 30. SR 207 is a 2-lane highway that runs southwest- northeast, starting at I-82 in the west, through Hermiston, and then intersecting with U.S. Highway 730 in the east. Table 3.6-1 summarizes the average daily traffic (ADT) and accident counts by milepost and location for these major roadways for 2001. -

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About the Highway Department

-mM WA STATE DOT LIBRARY 66 0009 9062 2 Everything you always wanted to know about the Highway Department Explained by The Washington State Highway Department * BUT DIDN'T KNOW WHO TO ASK DOT LIBRARY PO BOX 47425 OLYiViPlAVVA 98504-7425 360-705-7750 FOREWORD Although the title of our book is somewhat whimsical, the reader wil l find that the text is entirely serious in nature. We have l imited our report to "facts and figures" concerning the Highway Department and Washington State*s highway system, and have made no attempts to advance opinion or philosophy. We intend this book to be a reference guide for anyone - students, legislators, news media people and Highway Department employees - who need information on Washington's primary transportation system. Compi l ing the information for this book has been - and wi l l continue to be - a formidable task, requiring many hours and much di l igent research. The book you are now holding does not contain "everything" about the highway system; rather, ^it contains the information we have compiled so far and have included in it. More - much more - wi l l be forthcoming in the future. We wi l l send additional information to those who receive the book as it becomes avai lable, and we ask that those who want to stay up to date to supply the Publ ic Information Office with their names and addresses. We hope our book serves your needs and we wi l l welcome any suggestions, comments and criticisms you may care to give us regarding its contents.