Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programma Program

PROGRAMMA PROGRAM F.I.A. - C.S.A.I. F.M.I. ISCRIZIONI-ENTRY FORM APERTURA-OPENING mercoledì 7 settembre ore 8,00 CHIUSURA-CLOSING lunedì 3 ottobre ore 10,00 lunedì 26 settembre ore 10,00 VERIFICHE ANTE-GARA-SCRUTINEERING MELFI Municipio Sabato 8 ottobre 2011 Sportive con orari individuali dalle ore 9,30 alle ore 12,00 tecniche con orari individuali dalle ore 10,00 alle ore 12,30 BRIEFING CON DISTRIBUZIONE ROAD-BOOK MELFI Municipio Sala Consiliare Sabato 8 ottobre 2011 ore 9,00 ELENCO CONCORRENTI AMMESSI-STARTING LIST MELFI Municipio 1°piano Sabato 8 ottobre 2011 ore 13,00 PARTENZA-START MELFI P.za Mancini Sabato 8 ottobre 2011 1ª tappa _leg ore 14,01 Domenica 9 ottobre 2011 2ª tappa_leg ore 8,01 ARRIVO e PREMIAZIONE-ARRIVAL and PRIZE GIVING MELFI – P.za Mancini Sabato 8 ottobre 2011 1ª tappa_leg ore 20,41 Domenica 9 ottobre 2011 2ª tappa_leg ore 13,30 VERIFICHE POST GARA-AFTER RACE SCRUTINEERING MELFI – Off.Melfi Auto Domenica 9 ottobre 2011 dalle-from ore 13,30 via Pertini n°10 tel.0972 24338 SEGRETERIA E DIREZIONE DI GARA- SECRETARY AND RACE DIRECTION fino a Venerdì 7 ottobre 2011 SPORTS MARKETING & MANAGEMENT srl 85025 Zona Industriale S.NICOLA di MELFI (PZ) Tel. +39 0972 78242 Fax + 39 0972 762043 da Sabato 8 ottobre 2011 MELFI Municipio Tel 0972 251221 Fax 0972 251257 1 ALBO d’ORO_PALMARES RALLY PUGLIA & LUCANIA 1965 1ª edizione Volpi - “Black” Lancia Fulvia Bononi - Brandy Lancia Fulvia Filippi - Danieli Lancia Fulvia 1966 2ª edizione Cavallari - Munari Alfa GTA Bettoia Porsche Carrera Vacca Gordini R 8 1976 3ª edizione Di Gioia -

Evaluation of Herbal Medicinal Products

Evaluation of Herbal Medicinal Products Evaluation of Herbal Medicinal Products Perspectives on quality, safety and efficacy Edited by Pulok K Mukherjee Director, School of Natural Product Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India Peter J Houghton Emeritus Professor in Pharmacognosy, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, King’s College London, London, UK London • Chicago Published by the Pharmaceutical Press An imprint of RPS Publishing 1 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7JN, UK 100 South Atkinson Road, Suite 200, Grayslake, IL 60030-7820, USA © Pharmaceutical Press 2009 is a trade mark of RPS Publishing RPS Publishing is the publishing organisation of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain First published 2009 Typeset by J&L Composition, Scarborough, North Yorkshire Printed in Great Britain by Cromwell Press Group, Trowbridge ISBN 978 0 85369 751 0 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. The right of Pulok K Mukherjee and Peter J Houghton to be identified as the editors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library -

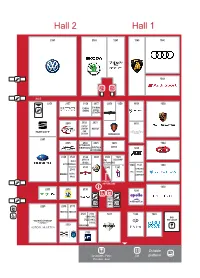

Hall 2 Hall 1

Format : 151mm x 210mm SPYCHER Hall 2 Hall 1 2161 2160 1261 1160 1060 1058 Hall 3 2251 2157 2158 2057 2056 1259 1159 1050 EADON TOURING GREEN SUPER- LEGGERA 2250 2150 2051 1151 ERTEX LUXURY WAYRAY CAR DESIGN 2241 2145 2146 2045 1245 1044 AUTOMOBILI PININFARINA PURITALIA ZENVO 1244 AUTOMOBILI 2240 2143 2144 2043 2042 1243 APPLUS DIZAYNVIP MOLE KW IDIADA AUTOMOTIVE AUTOMOBILES 1240 1141 1040 2142 2040 1241 2141 CHELSEA FIA TRUCK BREMBO AGVS / COMPANY UPSA KYBURZ SWITZERLAND 1030 2231 2232 2130 1230 1231 NOBE CARS 2229 2230 2131 TWISTED ENGLER 2124 2128 1221 1220 1020 CONCOURS BAR D’ELEGANCE THE LODGE SUISSE 2220 FORNASARI 2122 Outside Sandwiches - Panini Grill platform Pancakes - Beer Format : 300mm x 210mm SPYCHER Hall 6 6470 6271 6270 Hall 5 Hall 4 5250 4150 First aid 4251 4252 6461 6451 6360 6261 6260 6160 6061 6060 BAR MANIFATTURA LE PADDOCK PIRELLI MAGNA AUTOMOBILI QOODER TORINO PETRONAS 6350 6252 6050 5253 5261 5150 4247 4248 4149 SBB/CFF- KENDA SBB GREEN CLASS 6250 4147 Congress KLASSEN POLESTAR 4130 Hall 3 centre 6441 6440 6341 6340 6241 6240 6041 6040 5241 5240 5141 5043 5042 4241 4242 Hall 2 FREDY Restaurant AUTOMOBIL TOPCAR SIN CARS REVUE / BARTH Le Poulet Rôti OKCU HISPANO REVUE BAR LE RALLYE AUTOMOBILE 5140 5041 5040 SUIZA BRABUS STARTECH AUTO- 6239 IED Z’ART SCOUT24 Le Village ERDÖL-VEREINIGUNG / 4130 3000 Les cuisines du monde UNION PÉTROLIÈRE 5131 5130 5034 4233 4133 SHARE2DRIVE LUXARIA AUTO- TECHNOLOGY 5231 ILLUSTRIERTE 6421 6430 6331 6230 5032 DEVINCI QUATTRO- BAR CARESOFT LOUNGE RUOTE 4131 6428 GLOBAL ABARTH RCH 5030 -

Eight Secrets of Beijing Snapshots of a 3,000 Year-Old City

Barco company magazine • Volume 3 • Issue 6 magazine Eight secrets of Beijing Snapshots of a 3,000 year-old city Future past 10 accurate predictions from science fiction Tablet truths Can tablet PCs make it in healthcare? 1 redefine_issue_6c.indd 1 2/05/11 11:50 6 Eight secrets of beijing 24 million 735,000 Science pixels visitors Beauty is in the 1. 2. 3. Wireless communication Immersive 3D video conferencing It all just fits. Science fiction is notorious for its continuous attempts to make First mention: First mention: First mention: 1923, in H.G. Wells’s ‘Men like 1889, in Jules Verne’s ‘The Year 2889’ of the operator predictions about future technology. Even if it isn’t the central theme 1956, in Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘The City and the Stars’ Full display roll-out The enclosure for example, Gods’ 30 combines low weight, sealing, of its stories, it’s always involved on the side. And sometimes, it also Clarke described an immersive 3D setup in terms of gaming, and said: “You Video communication was and still is While the description in the common in science fiction, but its first at the Geneva Motor Show inspires scientists to make new technology breakthroughs. were an active participant and possessed—or seemed to possess—free will. booths low cost, noise damping, novel is fairly clunky, Wells The events […] might have been prepared beforehand, but there was enough mention predated the commercially made it clear that his characters flexibility to allow for wide variation.” Since the late 1980s, immersive 3D viable technology by nearly a century. -

Nómina De Magistrados Y Funcionarios Datos Al 05/09/2021

PODER JUDICIAL DE CORDOBA Nómina de Magistrados y Funcionarios Datos al 05/09/2021 Empleado Cargo Oficina Sede ANGULO MARTIN, Luis Eugenio VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA BLANC GERZICICH de ARABEL, Maria de las Mercedes VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA CACERES de BOLLATI, María Marta VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA LOPEZ PEÑA, Sebastián Cruz VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA RUBIO, Luis Enrique VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA SESIN, Domingo Juan VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA TARDITTI, Aida Lucia Teresa VOCAL TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DE JUSTICIA VOCALIA TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR CÓRDOBA BUSTOS FIERRO, Pablo Alfredo FISCAL ADJUNTO FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA DAVID, Hector Rene FISCAL ADJUNTO FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA GOMEZ DEMMEL, José Antonio FISCAL ADJUNTO FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA PAHL, Verónica del Valle SECRET.DE FISC.DE CAMARA FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA CARRERA, Pablo Daniel SECRETARIO/A DE FISCALIA FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA ESPOSITO, María Florencia AYUDANTE FISCAL FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA BALLISTRERI, Daniel PROSECRETARIO/A LETRADO FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA COPPINI, Gustavo Antonio PROSECRETARIO/A LETRADO FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA GENERAL CÓRDOBA MALUF, Daniela Karina PROSECRETARIO/A LETRADO FISCALIA ADJUNTA.-FISCALIA -

Bugatti in Italia

Bugatti in Italia AISA - Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile in collaborazione con Historic Club Schio - Bugatti Club Italia MONOGRAFIA AISA 100 AISA • Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile C.so di Porta Vigentina, 32 - 20122 Milano - www.aisastoryauto.it MONOGRAFIA AISA 100 60 ANNI Alessandro Colombo DAL IRCUITO DI IACENZA C P DALLA BIANCHI VITTORIO VALLETTA EBUTTO DELLA ERRARI D F ALLA BIANCHINA E LA FIAT AISA·Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile CPAE·Club Piacentino Automotoveicoli d’Epoca Didascalia AISA AISA Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile con la collaborazione di Bianchina Club Piacenza · Palazzo Farnese con la collaborazione di Fiat Group 16 giugno 2007 GIUSEPPE LURAGHI Milano 16 settembre 2007 Torino1 dicembre 2007 NELLA STORIA DELL’INDUSTRIA AUTOMOBILISTICA ITALIANA • Conferenza AISA·Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile /ISE·Istituto di Storia Economica PIACENZA dell’Università Bocconi 11 Sabato 26 maggio 2007- SDA Bocconi, MAGGIO Milano 1947 AISA ·Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile AISA ·Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile C.so di Porta Vigentina, 32 - 20122 Milano - www.aisastoryauto.it C.so di Porta Vigentina, 32 - 20122 Milano - www.aisastoryauto.it I AISA 100 AISA 100 Cento Monografie primo traguardo Aisa Lorenzo Boscarelli uando l’Aisa nacque, nel 1987, non credo che Possiamo ben dire, con un certo orgoglio, che Aisa dell’ingegner Domenico Beretta, ricco di centinaia disposizione di tutti, quindi va al di là della nostra Qi fondatori, tra i quali mi trovai anch’io, imma- ha contribuito a documentare la storia della moto- di volumi rari e di pubblicazioni varie di argomen- vicenda personale e associativa. -

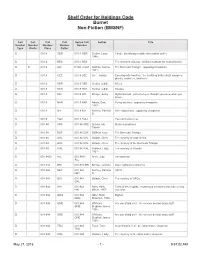

Shelf Order for Holdings Code Burnet Non-Fiction (BMSNF)

Shelf Order for Holdings Code Burnet Non-Fiction (BMSNF) Call Call Call Call Sorted Call Author Title Number Number Number Number Number Type Prefix Class Cutter D 001.4 GER 001.4 GER Gerber, Larry, Cited! : identifying credible information online 1946- D 001.4 RES 001.4 RES The research virtuoso : brilliant methods for normal brains D R 001.9 Gaf R 001.9 Gaf Gaffron, Norma, The Bermuda Triangle : opposing viewpoints 1931- D 001.9 GEE 001.9 GEE Gee, Joshua Encyclopedia horrifica : the terrifying truth! about vampires, ghosts, monsters, and more D 001.9 HER 001.9 HER Herbst, Judith. Aliens D 001.9 HER 001.9 HER Herbst, Judith. Hoaxes D 001.9 KRI 001.9 KRI Krieger, Emily Myths busted! : just when you thought you knew what you knew-- D 001.9 NAR 001.9 NAR Nardo, Don, Flying saucers : opposing viewpoints 1947- D 001.9 Net 001.9 Net Netzley, Patricia Alien abductions : opposing viewpoints D. D 001.9 YOU 001.9 YOU You can't scare me!. D 001.94 ANS 001.94 ANS Ansary, Mir Mysterious places Tamim D 001.94 DUF 001.94 DUF Duffield, Katy The Bermuda Triangle D 001.94 OXL 001.94 OXL Oxlade, Chris The mystery of crop circles D 001.94 OXL 001.94 OXL Oxlade, Chris The mystery of the Bermuda Triangle D 001.94 WAL 001.94 WAL Wallace, Holly, The mystery of Atlantis 1961- D 001.9403 ALL 001.9403 Allen, Judy Unexplained ALL D 001.942 BRI 001.942 BRI Bringle, Jennifer Alien sightings in America D 001.942 NET 001.942 Netzley, Patricia UFO's NET D. -

Role of Microorganisms Present in Dairy Fermented Products in Health and Disease Neural Computation for Rehabilitation Guest Editors: Clara G

BioMed Research International Role of Microorganisms Present in Dairy Fermented Products in Health and Disease Neural Computation for Rehabilitation Guest Editors: Clara G. de los Reyes-Gavilán, María Fernández, John Andrew Hudson, and Riitta Korpela Role of Microorganisms Present in Dairy Fermented Products in Health and Disease BioMed Research International Role of Microorganisms Present in Dairy Fermented Products in Health and Disease Guest Editors: Clara G. de los Reyes-Gavilan,´ Marc´ıa Fern´ındez, John Andrew Hudson, and Riitta Korpela Copyright © 2015 Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in “BioMed Research International.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Contents Role of Microorganisms Present in Dairy Fermented Products in Health and Disease, Clara G. de los Reyes-Gavilan,´ Marc´ıa Fern´ındez, John Andrew Hudson, and Riitta Korpela Volume 2015, Article ID 204173, 2 pages Antimicrobial Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Dairy Products and Gut: Effect on Pathogens, Juan L. Arques,´ Eva Rodr´ıguez, Susana Langa, JoseMar´ ´ıa Landete, and Margarita Medina Volume2015,ArticleID584183,9pages Impact on Human Health of Microorganisms Present in Fermented Dairy Products: An Overview, Mar´ıa Fernandez,´ John Andrew Hudson, Riitta Korpela, and Clara G. de los Reyes-Gavilan´ Volume 2015, Article ID 412714, 13 pages Bioaccessible Antioxidants in Milk Fermented by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum Strains, Merilie´ Gagnon, Patricia Savard, Audrey Riviere,` Gisele` LaPointe, and Denis Roy Volume 2015, Article ID 169381, 12 pages Biodiversity and gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Alpine Raw Cow’s Milk Cheeses, Elena Franciosi, Ilaria Carafa, Tiziana Nardin, Silvia Schiavon, Elisa Poznanski, Agostino Cavazza, Roberto Larcher, and Kieran M. -

ALBO D'oro – PALMARES

ALBO d’ORO – PALMARES RALLY PUGLIA & LUCANIA Campionato Italiano Rally MOBIL - MARLBORO 1965 1ª edizione 1°Volpi - “Black” Lancia Fulvia HF Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Bononi - Brandy Lancia Fulvia HF 3°Filippi - Danieli Lancia Fulvia HF 1966 2ª edizione 1°Cavallari - Munari Alfa Romeo Giulia GTA Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Bettoia Porsche Carrera 3°Vacca Renault R 8 Gordini 1976 3ª edizione 1°Di Gioia - Mastrorosa Porsche Carrera Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Ruggiero - Pennetta Fiat 124 Abarth 3°Tommasi - Cillo Lancia Fulvia HF 1977 4ª edizione 1°Lipizer - Cernigai Porsche Carrera RS Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Di Gioia - Mastrorosa Porsche Carrera RS 3°Scudieri - Perri Porsche Carrera RS 1978 5ª edizione 1°Scudieri - Pizzi Porsche Carrera RS Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Stoppato - Loiacono Ford Escort RS 2000 3°Volonnino - Marcone Opel Kadett GTE 2.0 1979 6ª edizione 1°Cane - Orlando Fiat 131 Abarth Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Casarotto - Zonta Lancia Stratos 3°Vacchini - Calderoli Opel Kadett GTE 2.0 1 1980 7ª edizione 1°Betti - Betti Lancia Stratos Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Mirri - Rancati Fiat Ritmo 75 Gr.2 3°Cerutti - Stradella Fiat 131 Abarth 1981 8ª edizione 1°Pasutti - Bisol Porsche 911 Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Biasuzzi - Piantanida Lancia Stratos 3°Riva - Gerbaldo Opel Ascona 400 1982 9ª edizione 1°Cuccirelli - Muttini Porsche 911 3.0 Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Di Gioia - Oliva Porsche 911 3.0 3°Scudieri - Pizzi Porsche 911 3.0 1983 10ª edizione 1°Boretti - Boretti Lancia Rally 037 Bari-P.za Prefettura 2°Chiossi - Chiossi Porsche 930 Turbo 3° “Pau” - Roggia Lancia Rally 037 Trofeo Provincia di Bari - Coppa Italia Rally VII^zona 1992 11ª edizione 1°Tradico - Tradico Lancia Delta 16V Gr. -

Wild Plants and Their Associated Insects in The

Abstract Campobasso, G., E. Colonnelli, L. Knutson, G. Copies of this publication may be purchased from Terragitti, and M. Cristofaro, eds. 1999. Wild the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Plants and Their Associated Insects in the Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161; telephone Palearctic Region, Primarily Europe and the Middle (703) 605–6000. East. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, ARS–147, 249 pp. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs This book compiles information on palearctic and activities on the basis of race, color, national insects that were collected or reared from 166 origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political species of plants of Eurasian origin. The insect beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family species are listed taxonomically and by host plant. status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all The host plant list includes data on rearing, feeding, programs.) Persons with disabilities who require and other insect-plant associations. A third list alternative means for communication of program includes parasites of the insect species. information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at Information on the insects was obtained during the 202–720–2600 (voice and TDD). course of studies on biological control of weeds by staff of the Biological Control of Weeds To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Laboratory-Europe, Rome, Italy, and European Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326–W, Biological Control Laboratory, Montpellier, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, France, from 1959 through 1995. Included are the SW, Washington, DC 20250–9410 or call data presented by Pemberton and Hoover (1980) 202–720–5964 (voice or TDD). -

GENEVA INTERNATIONAL MOTOR SHOW 2019 Etat Au 07.02.2018

GENEVA INTERNATIONAL MOTOR SHOW 2019 Etat au 07.02.2018 Enseigne Stand Société Ville Site web - Compte ABT 1244 ABT SPORTSLINE GMBH DE-87437 KEMPTEN www.abt-sportsline.de ACS 2043 AUTOMOBIL CLUB DER SCHWEIZ (ACS) CH-3000 BERN 13 www.acs.ch AUTOGEWERBEVERBAND DER SCHWEIZ AGVS / UPSA 2141 CH-3000 BERN 22 www.agvs.ch (AGVS) AIWAYS | GUMPERT 2220 GUMPERT AIWAYS AUTOMOBILE GMBH DE-85053 INGOLSTADT www.rolandgumpert.com ALFA ROMEO 5131 ALFA ROMEO - FCA SWITZERLAND SA CH-8952 SCHLIEREN www.alfaromeopress.ch AMG 6461 MERCEDES-BENZ SCHWEIZ AG - AMG CH-8952 SCHLIEREN www.mercedes-benz.ch AMSTUTZ PRODUKTE 7111 AMSTUTZ PRODUKTE AG CH-6274 ESCHENBACH LU www.amstutz.com APOLLO VREDESTEIN 1230 APOLLO VREDESTEIN SCHWEIZ AG CH-5402 BADEN www.vredestein.com APPLUS IDIADA 2144 IDIADA AUTOMOTIVE TECHNOLOGY SA ES-43710 SANTA OLIVA www.applusidiada.com AQUARAMA 7221-SP AQUARAMA SWISS AG CH-5036 OBERENTFELDEN www.aquaramaswiss.ch ARAMCO 6420 SAUDI ARAMCO SA-31311 DHAHRAN www.saudiaramco.com BEIJING ELECTRIC VEHICLE MARKETING CO., ARCFOX 1040 CN-100176 BEIJING www.arcfox.cn LTD ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA 2229 ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA LTD UK-CV35 0DB GAYDON, WARWICK www.astonmartin.com AUDI 1060 AMAG IMPORT AG AUDI CH-5116 SCHINZNACH-BAD www.audi.ch AUDI SPORT 1058 AMAG IMPORT AG AUDI SPORT CH-5116 SCHINZNACH-BAD FSUE NAMI AURUS 1221 RUSSIAN STATE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH RU-125438 MOSCOW www.aurusmotors.com CENTER AUTO-I-DAT 7211-SP AUTO-I-DAT AG CH-8038 ZUERICH www.auto-i-dat.ch AUTOMOBIL REVUE / REVUE 6241 ABOFLOR AG CH-3172 NIEDERWANGEN BE AUTOMOBILE www.automobili- AUTOMOBILI -

Latest Updated CV

University of Florida Sara Rampazzi Florida Institute for Cybersecurity Department of Computer and Information 601 Gale Lemerand Dr, Science and Engineering Gainesville, FL 32603 [email protected] sararampazzi.com Research Embedded hardware security, embedded systems design, modeling, and areas simulation with application to medical devices, automotive, and IoT Education PhD in Electronics, Computer Science and Electrical Engineering University of Pavia (Italy), 2014. MEng in Computer Science Engineering University of Pavia (Italy), 2010. BS in Computer Science Engineering University of Pavia (Italy), 2008. Grants and PI: awards Facebook Award Explorations of Trust in AR, VR, and Smart Devices, 2020 Co-PI: NSF Grant Award #2031077: RAPID: SaTC: COVID19: Science of using wirelessly powered sensors to quickly scale up verifiable decontamination of individual N95 respirator masks, 2020 Academic Assistant Professor Jan 2021-Present positions Computer & Information Science & Engineering University of Florida Research Investigator Feb 2018-Dec 2020 Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, University of Michigan Intermittent Lecturer Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, Jan 2019-Jan 2020 University of Michigan Affiliate Researcher Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, Aug 2017-Jan 2018 University of Michigan Postdoc fellow 2014 Computer Science Engineering, University of Pavia Last Update: Jan 2021 S. Rampazzi (1) Research Senior personnel on THAW 2018-2021 experience University of Michigan Principal Researcher for MCity PASS project