And Glamorous Hollywood Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

“Al-Tally” Ascension Journey from an Egyptian Folk Art to International Fashion Trend

مجمة العمارة والفنون العدد العاشر “Al-tally” ascension journey from an Egyptian folk art to international fashion trend Dr. Noha Fawzy Abdel Wahab Lecturer at fashion department -The Higher Institute of Applied Arts Introduction: Tally is a netting fabric embroidered with metal. The embroidery is done by threading wide needles with flat strips of metal about 1/8” wide. The metal may be nickel silver, copper or brass. The netting is made of cotton or linen. The fabric is also called tulle-bi-telli. The patterns formed by this metal embroidery include geometric figures as well as plants, birds, people and camels. Tally has been made in the Asyut region of Upper Egypt since the late 19th century, although the concept of metal embroidery dates to ancient Egypt, as well as other areas of the Middle East, Asia, India and Europe. A very sheer fabric is shown in Ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. The fabric was first imported to the U.S. for the 1893 Chicago. The geometric motifs were well suited to the Art Deco style of the time. Tally is generally black, white or ecru. It is found most often in the form of a shawl, but also seen in small squares, large pieces used as bed canopies and even traditional Egyptian dresses. Tally shawls were made into garments by purchasers, particularly during the 1920s. ملخص البحث: التمي ىو نوع من انواع االتطريز عمى اقمشة منسوجة ويتم ىذا النوع من التطريز عن طريق لضم ابر عريضة بخيوط معدنية مسطحة بسمك 1/8" تصنع ىذه الخيوط من النيكل او الفضة او النحاس.واﻻقمشة المستخدمة في صناعة التمي تكون مصنوعة اما من القطن او الكتان. -

Nancy Wilson Ross

Nancy Wilson Ross: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Title: Nancy Wilson Ross Papers Dates: 1913-1986 Extent: 261.5 document boxes, 12 flat boxes, 18 card boxes, 7 galley folders (138 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this American writer encompass her entire literary career and include manuscript drafts, extensive correspondence, and subject files reflecting her interest in Eastern cultures. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03616 Language: English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1972 (R5717) Provenance Ross's first shipment of materials to the Ransom Center accompanied her husband Stanley Young's papers, and consisted of Ross's literary output to 1975, including manuscripts, publications, and research materials. The second, posthumous shipment contained manuscripts created since 1974, and all her correspondence, personal, and financial files, as well as files concerning the estate of Stanley Young. Processed by Rufus Lund, 1992-93; completed by Joan Sibley, 1994 Processing note: Materials from the 1975 and 1986 shipments are grouped following Ross's original order, with the exception of pre-1970, special, and current correspondence which were interfiled during processing. An index of selected correspondents follows at the end of this inventory. Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Manuscript Collection MS-03616 2 Ross, Nancy Wilson, 1901-1986 Manuscript Collection MS-03616 Biographical Sketch Nancy Wilson was born in Olympia, Washington, on November 22, 1901. She graduated from the University of Oregon in 1924, and married Charles W. -

Puvunestekn 2

1/23/19 Costume designers and Illustrations 1920-1940 Howard Greer (16 April 1896 –April 1974, Los Angeles w as a H ollywood fashion designer and a costume designer in the Golden Age of Amer ic an cinema. Costume design drawing for Marcella Daly by Howard Greer Mitc hell Leis en (October 6, 1898 – October 28, 1972) was an American director, art director, and costume designer. Travis Banton (August 18, 1894 – February 2, 1958) was the chief designer at Paramount Pictures. He is considered one of the most important Hollywood costume designers of the 1930s. Travis Banton may be best r emembered for He held a crucial role in the evolution of the Marlene Dietrich image, designing her costumes in a true for ging the s tyle of s uc h H ollyw ood icons creative collaboration with the actress. as Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae Wes t. Costume design drawing for The Thief of Bagdad by Mitchell Leisen 1 1/23/19 Travis Banton, Travis Banton, Claudette Colbert, Cleopatra, 1934. Walter Plunkett (June 5, 1902 in Oakland, California – March 8, 1982) was a prolific costume designer who worked on more than 150 projects throughout his career in the Hollywood film industry. Plunk ett's bes t-known work is featured in two films, Gone with the Wind and Singin' in the R ain, in which he lampooned his initial style of the Roaring Twenties. In 1951, Plunk ett s hared an Osc ar with Orr y-Kelly and Ir ene for An Amer ic an in Paris . Adr ian Adolph Greenberg ( 1903 —19 59 ), w i de l y known Edith H ead ( October 28, 1897 – October 24, as Adrian, was an American costume designer whose 1981) was an American costume designer mos t famous costumes were for The Wiz ard of Oz and who won eight Academy Awards, starting with other Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and The Heiress (1949) and ending with The Sting 1940s. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

Final J.Min |O.Phi |T.Cun |Editor |Copy

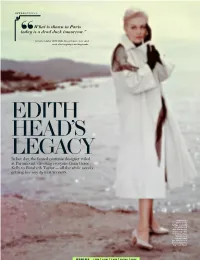

Style SPeCIAl What is shown in Paris today is a dead duck tomorrow.” — Costume designer EDITH HEAD, whose 57-year career owed “ much of its longevity to avoiding trends. C Edith Head’s LEgacy In her day, the famed costume designer ruled at Paramount, dressing everyone from Grace Kelly to Elizabeth Taylor — all the while savvily getting her way By Sam Wasson Kim Novak’s wardrobe for Vertigo, including this white coat with black scarf, was designed to look mysterious. “This girl must look as if she’s just drifted out of the San Francisco fog,” said Head. FINAL J.MIN |O.PHI |T.CUN |EDITOR |COPY Costume designer edith head — whose most unforgettable designs included Grace Kelly’s airy chiffon skirt in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, Gloria Swanson’s darkly elegant dresses in Sunset Boulevard, Dorothy Lamour’s sarongs, and Elizabeth Taylor’s white satin gown in A Place in the Sun — sur- vived 40 years of changing Hollywood styles by skillfully eschewing fads of the moment and, for the most part, gran- Cdeur and ornamentation, too. Boldness, she believed, was a vice. Thirty years after her death, Head is getting a new dose of attention. A gor- geous coffee table book,Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer, was recently published. And in late March, an A to Z adapta- tion of Head’s seminal 1959 book, The Dress Doctor, is being released as well. ! The sTyle setter of The screen The breezy volume spotlights her trade- Clockwise from above: 1. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

During the 1930-60'S, Hollywood Directors Were Told to "Put the Light Where the Money Is" and This Often Meant Spectacular Costumes

During the 1930-60's, Hollywood directors were told to "put the light where the money is" and this often meant spectacular costumes. Stuidos hired the biggest designers and fashion icons to bring to life the glitz and the glamour that moviegoers expected. Edith Head, Adrian, Walter Plunkett, Irene and Helen Rose were just a few that became household names because of their designs. In many cases, their creations were just as important as the plot of the movie itself. Few costumes from the "Golden Era" of Hollywood remain except for a small number tha have been meticulously preserved by a handful of collectors. Greg Schreiner is one of the most well-known. His wonderful Hollywood fiolm costume collection houses over 175 such masterpieces. Greg shares his collection in the show Hollywoood Revisited. Filled with music, memories and fun, the revue allows the audience to genuinely feel as if they were revisiting the days that made Hollywood a dream factory. The wardrobes of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Julie Andrews, Robert Taylor, Bette Davis, Ann-Margret, Susan Hayward, Bob Hope and Judy Garland are just a few from the vast collection that dazzle the audience. Hollywood Revisited is much more than a visual treat. Acclaimed vocalists sing movie-related music while modeling the costumes. Schreiner, a professional musician, provides all the musical sccompaniment and anecdotes about the designer, the movie and scene for each costume. The show has won critical praise from movie buffs, film historians, and city-wide newspapers. Presentation at the legendary Pickfair, The State Theatre for The Los Angeles Conservancy and The Santa Barbara Biltmore Hotel met with huge success. -

HH Available Entries.Pages

Greetings! If Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History sounds like a project you would like be involved with, whether on a small or large-scale level, I would love to have you on-board! Please look at the list of names below and send your top 3 choices in descending order to [email protected]. If you’re interested in writing more than one entry, please send me your top 5 choices. You’ll notice there are several women who will have a “D," “P," “W,” and/or “A" following their name which signals that they rightfully belong to more than one category. Due to the organization of the book, names have been placed in categories for which they have been most formally recognized, however, all their roles should be addressed in their individual entry. Each entry is brief, 1000 words (approximately 4 double-spaced pages) unless otherwise noted with an asterisk. Contributors receive full credit for any entry they write. Deadlines will be assigned throughout November and early December 2017. Please let me know if you have any questions and I’m excited to begin working with you! Sincerely, Laura Bauer Laura L. S. Bauer l 310.600.3610 Film Studies Editor, Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal Ph.D. Program l English Department l Claremont Graduate University Cross-reference Key ENTRIES STILL AVAILABLE Screenwriter - W Director - D as of 9/8/17 Producer - P Actor - A DIRECTORS Lois Weber (P, W, A) *1500 Major early Hollywood female director-screenwriter Penny Marshall (P, A) Big, A League of Their Own, Renaissance Man Martha -

DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume Sketches and Costume Concept Art in the Filmmaking Process

Laura Malinen 2017 DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume sketches and costume concept art in the filmmaking process MA thesis Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Department of Film, Television and Scenography Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television Major in Costume Design 30 credits Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Sofia Pantouvaki and Satu Kyösola for the invaluable help I got for this thesis. I would also like to thank Nick Keller, Anna Vilppunen and Merja Väisänen, for sharing their professional expertise with me. Author Laura Malinen Title of thesis Drawing Costumes, Portraying Characters – Costume sketches and costume concept art in the filmmaking process Department Department of Film, Television and Scenography Degree programme Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television. Major in Costume Design Year 2017 Number of pages 85 Language English Abstract This thesis investigates the various types of drawing used in the process of costume design for film, focusing on costume sketches and costume concept art. The research question for this thesis is ‘how and why are costume sketches and costume concept art used when designing costumes for film?’ The terms ‘costume concept art’ and ‘costume sketch’ have largely been used interchangeably. My hypothesis is that even though costume sketch and costume concept art have similarities in the ways of usage and meaning, they are, in fact, two separate, albeit interlinked and complementary terms as well as two separate types of professional expertise. The focus of this thesis is on large-scale film productions, since they provide the most valuable information regarding costume sketches and costume concept art. -

Silent Film Music and the Theatre Organ Thomas J. Mathiesen

Silent Film Music and the Theatre Organ Thomas J. Mathiesen Introduction Until the 1980s, the community of musical scholars in general regarded film music-and especially music for the silent films-as insignificant and uninteresting. Film music, it seemed, was utili tarian, commercial, trite, and manipulative. Moreover, because it was film music rather than film music, it could not claim the musical integrity required of artworks worthy of study. If film music in general was denigrated, the theatre organ was regarded in serious musical circles as a particular aberration, not only because of the type of music it was intended to play but also because it represented the exact opposite of the characteristics espoused by the Orgelbewegung of the twentieth century. To make matters worse, many of the grand old motion picture theatres were torn down in the fifties and sixties, their music libraries and theatre organs sold off piecemeal or destroyed. With a few obvious exceptions (such as the installation at Radio City Music Hall in New (c) 1991 Indiana Theory Review 82 Indiana Theory Review Vol. 11 York Cityl), it became increasingly difficult to hear a theatre organ in anything like its original acoustic setting. The theatre organ might have disappeared altogether under the depredations of time and changing taste had it not been for groups of amateurs that restored and maintained some of the instruments in theatres or purchased and installed them in other locations. The American Association of Theatre Organ Enthusiasts (now American Theatre Organ Society [ATOS]) was established on 8 February 1955,2 and by 1962, there were thirteen chapters spread across the country. -

Damiani Cat Fall 2018.Pdf

Fall 2018 Contents New Titles 5 Collector’s Editions 49 Toiletpaper 71 Backlist 77 Photography 78 Fashion & Lifestyle 94 Contemporary Art 96 Music 100 Urban Art 101 Architecture & Design 102 Antiques & Collectibles 103 Spazio Damiani 104 Distributors 106 Notes 108 Contacts 110 New Titles Photography Arthur Elgort Jazz This is the first book dedicated to Elgort’s Jazz portraits and the list of names it includes constitutes a veritable pantheon of jazz greatness. Featured in the book are portraits of Wynton Marsalis, James Carter, Roy Haynes, George Benson, Milt Hinton, Walter Blanding, Michael Bowie, David Sanchez, Angelo Debarre, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, Joshua Redman, James Moody, Jay McShann, Pat McFeeny, Jimmy Scott, Dorothy Donegan, Illinois Jacquet, Ornette Coleman, Don Byron, Aaron Neville, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, John McLaughlin, Jesse Davis, Lionel Hampton, Clark Terry, Christian Mcades, Ron Carter, Wycliff Gordon, Sam Newsome, Roy Haynes, Jon Faddis, Roy Hargrove, Max Roach, Jerome Harris, Jack DeJohnette, Michael Cain, Al Grey, Thelonius Monk Jr., Benny Carter, Jon Hendricks, Stefan Harris, Jervan Jackson, Kenny Baron, Doc Cheatham, Arnett Cob, Tommy Flanagan, Jason Moran, Luther Lafatti, Bradford Marsalis, Delfeayo Marsalis, Jason Marsalis, Kenny Garrett, Olu Dara, Jesse Davis, Buddy Tate, Anton Rooney, Flip Phillips, and Sam Rivers. Every now and then a fashion model of Foreword by Wynton Marsalis. Introduction by the moment pops up in a picture, creating a fitting link between Hank O’Neal. Edited by Marianne Houtenbos this body of work and Elgort’s fashion pictures. 17.8 x 22.9 cm | 7 x 9 inches 160 pages, 100 color and b&w, hardbound ISBN 978-88-6208-608-0 Arthur Elgort was born and raised in New York.