TOCC0358DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toccata Classics TOCC0147 Notes

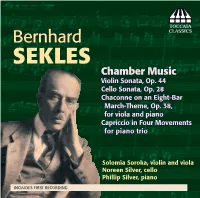

TOCCATA Bernhard CLASSICS SEKLES Chamber Music Violin Sonata, Op. 44 Cello Sonata, Op. 28 Chaconne on an Eight-Bar March-Theme, Op. 38, for viola and piano ℗ Capriccio in Four Movements for piano trio Solomia Soroka, violin and viola Noreen Silver, cello Phillip Silver, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDING REDISCOVERING BERNHARD SEKLES by Phillip Silver he present-day obscurity of Bernhard Sekles illustrates how porous is contemporary knowledge of twentieth-century music: during his lifetime Sekles was prominent as teacher, administrator and composer alike. History has accorded him footnote status in two of these areas of endeavour: as an educator with an enviable list of students, and as the Director of the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt from 923 to 933. During that period he established an opera school, much expanded the area of early-childhood music-education and, most notoriously, in 928 established the world’s irst academic class in jazz studies, a decision which unleashed a storm of controversy and protest from nationalist and fascist quarters. But Sekles was also a composer, a very good one whose music is imbued with a considerable dose of the unexpected; it is traditional without being derivative. He had the unenviable position of spending the prime of his life in a nation irst rent by war and then enmeshed in a grotesque and ultimately suicidal battle between the warring political ideologies that paved the way for the Nazi take-over of 933. he banning of his music by the Nazis and its subsequent inability to re-establish itself in the repertoire has obscured the fact that, dating back to at least 99, the integration of jazz elements in his works marks him as one of the irst European composers to use this emerging art-form within a formal classical structure. -

Hans Rosbaud and the Music of Arnold Schoenberg Joan Evans

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 01:22 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Hans Rosbaud and the Music of Arnold Schoenberg Joan Evans Volume 21, numéro 2, 2001 Résumé de l'article Cette étude documente les efforts de Hans Rosbaud (1895–1962) pour URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014484ar promouvoir la musique d’Arnold Schoenberg. L’essai est en grande partie basé DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014484ar sur vingt années de correspondance entre le chef d’orchestre et le compositeur, échange demeuré inédit. Les tentatives de Rosbaud portaient déjà fruit Aller au sommaire du numéro pendant qu’il était en fonction à la radio de Francfort au début des années 1930. À la suite de l’interruption forcée due aux années nazies (au cours desquelles il a travaillé en Allemagne et dans la France occupée), Rosbaud a Éditeur(s) acquis une réputation internationale en tant que chef d’orchestre par excellence dédié aux œuvres de Schoenberg. Ses activités en faveur de Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités Schoenberg dissimulaient le projet, que la littérature sur celui-ci n’avait pas canadiennes encore relevé, de ramener le compositeur vieillissant en Allemagne. ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Evans, J. (2001). Hans Rosbaud and the Music of Arnold Schoenberg. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 21(2), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014484ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

“The Librettist Wears Skirts”: Female Librettists in 19Th-Century Bohemia

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara “The Librettist Wears Skirts”: Female Librettists in 19th-Century Bohemia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Emma Taylor Parker Committee in charge: Professor Derek Katz, Chair Professor David Paul Professor Stefanie Tcharos June 2016 The dissertation of Emma Taylor Parker is approved. ___________________________________________________________ David Paul ___________________________________________________________ Stefanie Tcharos ___________________________________________________________ Derek Katz, Committee Chair June 2016 “The Librettist Wears Skirts”: Female Librettists in 19th-Century Bohemia Copyright © 2016 By Emma Taylor Parker iii Acknowledgements Writing a dissertation is not for the faint of heart and I certainly would not have finished this dissertation without a veritable village of supporters. I would like to thank the Fulbright Commission in the Czech Republic who sponsored my research year in Prague, especially Dr. Hanka Ripková, director of the commission, who was a truly hospitable host, and Andrea Semancová who patiently answered innumerable questions along every step of the journey. I am so grateful to them and the rest of the wonderful staff for their support, both financial and emotional. I am also grateful to Dr. Jarmila Gabrielová who sponsored my Fulbright application and was, along with her students, gracious in welcoming me to her graduate seminar at Charles University and extremely helpful in pointing me in the right direction during my time there. Haig Utidijian and the Charles University Chorus afforded me incomparable performing opportunities, a much-needed musical outlet during my time in Prague, and most of all, their warm friendship. And of course, without my fellow Fulbrighters (especially Laura Brade and John Korba) I would have been on a plane home more times that I can count. -

DISCOGRAPHY of SPOHR's SYMPHONIES This Discography Is in Two Parts

DISCOGRAPHY OF SPOHR'S SYMPHONIES This discography is in two parts. The catalogue numbers of the various recordings can be found under the entry for each syrnphony. For details of the full contents of each disc, cross-refer to the list of record labels. All recordings are CD unless stated. Symphony No.l in E flat major, Op.20 cpo 7 7 7 l7 9 -2; Hyperion CD A67 61 6; Marco Polo 8.2233 63 . Symphony No.2 in D minor, Op.49 cpo 777178-2; Hyperion CDA 67616; Marco Polo 8.220360 (LP 6.220360), CD reissue on Naxos 8.573507; Marco Polo 8.223454. Symphony No.3 in C minor, Op.78 Amati SRR8904/1; cpo 777177-2; Hyperion CDA67788; Koch Schwann CDll620 (LP Schwann Musica Mundi VMSl620); Marco Polo 8.223439; RBM Musikproduktion (LP) RBM 3035; Urania (LP) URLP5008. Symphony No.4 in F major, Op.86 cpo 777745-2; Hyperion 67622; Marco Polo 8.223122. Symphony No.5 in C minor, Op.102 cpo 777745-2; Hyperion 67622; Marco Polo 8.223363. Symphony No.6 in G major, Op.116 cpo777179-2; Hyperion CDA67788; Marco Polo 8.223439; Orfeo C094841A (LP S094841A). Symphony No.7 in C major, Op.121 cpo 777746-2; Hyperion CDA67939; Marco Polo 8.223432. Symphony No.8 in G major, Op.137 cpo777178-2; Hyperion CDA67802; Marco Polo 8.223432. Symphony No.9 in B minor, Op.143 cpo 777746-2; Hyperion CDA67939; Marco Polo 8.223454; Orfeo C094841A (LP S094841A). Symphony No.10 in E flat major, WoO.8 cpo 777177-2; Hyperion CDA67802 RECORD COMPANIES Note that the playing time for each symphony recording is given. -

Musik Aus Versailles Werke Von Louis-Gabriel Guillemain, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Georg Philipp Telemann, Jean-Marie Leclair Und Anderen

Kammermusik im Bibliothekssaal des Agrarbildungszentrums Landsberg am Lech Sonntag 25. Februar 2018, 18 Uhr Mendelssohn II Jugend & Alter Joseph Haydn, Ignaz Lachner und Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Rodin Quartett Sonja Korkeala, Gerhard Urban, Violine Martin Wandel, Viola // Clemens Weigel, Violoncello www.kammermusik-landsberg.de Programm Ignaz Lachner (1807 – 1895): Streichquartett Nr. 5 G-Dur op. 104 • Allegro ma non troppo • Andante grave • Allegro vivace • Allegro vivace Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809): Streichquartett G-Dur op. 77/1 Hob.III:81 (1799) • Allegro moderato • Adagio • Menuetto. Presto • Finale. Presto – Pause – Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809 – 1847): Streichquartett a-moll op. 13 (1827) • Adagio – Allegro vivace • Adagio non lento • Intermezzo. Allegretto con moto – Allegro di molto • Finale. Presto – Adagio non lento Ich bin eben im Begriff ein Violin-quartett zu beendigen, es ist zum Weinen sentimental und sonst nicht übel glaube ich. Mendelssohn am 23. Oktober 1827 „Was dein Schüler jetzt schon leistet, mag sich zum damaligen Mozart verhalten wie die ausgebildete Sprache eines Erwachsenen zum Lallen eines Kindes.“ Goethe im Jahr 1821 an Mendelssohns Lehrer Carl Friedrich Zelter Einer der härtesten und dringlichsten Sozialhilfefälle wären sie heutzutage, die Lachners, die im späten 18. und im früheren 19. Jahrhundert im Organisten- häuschen der altbayerischen Stadt Rain am Lech ihr kärgliches Dasein fristeten. Kaum mehr als siebzig Quadratmeter maß die Dienstwohnung des katholischen Stadtpfarrorganisten. Keller gab es -

Cultural Death Music Under Tyranny Kabasta • Hoehn • Fried

Cultural Death Music under Tyranny Kabasta • Hoehn • Fried Cultural Death: Music under Tyranny Oswald Kabasta • Alfred Hoehn • Oskar Fried Lost artifacts by three musicians have resurfaced out of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union, each of whom arrived at a horrid end. The Nazis had implemented a program 1. Beethoven: Leonore Overture, no. 2 13'10" of bringing forcible-coordination to all their ideas and goals, known as gleichschaltung, an Oswald Kabasta conducting the Munich Philharmonic electrical term that involves the “switching” of elements to be compatible within a circuit, or rec. c. 1942-44. unissued 2RA 5690/3 previously unpublished power system: this concept is an apt description of Nazification. It fueled Kabasta's success whereas Hoehn and Fried were unadaptable outsiders whose artistic and personal integrity 2. Brahms: Piano Concerto no. 2, Op. 86: I. Allegro non troppo 15"39" remain with us, living on in the deep spirituality evident in their recorded performances. Alfred Hoehn, piano; Reinhold Merten conducting the Leipzig Radio Orchestra The Nazis’ broad rise on the cultural front began in 1920 when they relaunched the rec. 1940.4.5. licensed from RBB Media previously unpublished failed Völkischer Beobachter newspaper. A respectable pseudo-intellectual facade lured the German public into accepting an ideology that viewed the past through a pathologically Berlioz: Symphony fantastique 50'10" distorted lens, while imposing their National Socialist revisionism onto a millennial chain 3. I. Rêveries – Passions. 14'26" of disparate historic events and personages. Their articles progressively manipulated every 4. II. Un bal. Valse. 6'55' well-known protagonist, past or present, German or otherwise. -

ARSC Journal

HANS ROS BAUD: A DISCOGRAPHY by Les lie Gerber Hans Rosbaud was born in Graz, Austria, on July 22, 1895. His major studies were at the music conservatory of Frankfurt am Main. In 1929 be was appointed to his first major post, director of the Mainz School of Music. He left the following year to become conductor-in-chief of Radio Frankfurt. During World War II he was musical director of the city of Strasbourg. In 1945 he became conductor of the Munich Philharmonic. Rosbaud's most important appointment was made in 1948, when he was picked to reorganize and conduct the orchestra which became the Southwest German Radio Orchestra of Baden-Baden. Although devoting him self to other projects as well, Rosbaud's main interest seems to have been the Baden-Baden orchestra, of which he remained director until his death. In 1952 he be came conductor of the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, and in 1958 was made chief conductor of the Zurich Stadt theater. Other activities of Rosbaud's last years were his appearances at the Aix-en-Provence Festival and at the Donaueschinger Musiktage. He died in Lugano, Switzerland, on December 29, 1962. Rosbaud occupies a virtually unique position in the history of conducting. Almost alone among conductors of his generation (Hermann Scherchen is perhaps the only other example), he was as devoted to the most ad vanced productions of the contemporary avant-garde as to the works of the great classical tradition. As early as 1933 he bad the honor of conducting the first per formance of Bart6k's Piano Concerto No. -

Kaim-Chor) 30.12.96 Te Deum Meta Hieber (S), Elisabeth Exter (A), U

Munich Philharmonic Bruckner Concerts (1896 – 1954) Between 1896 and 1902 Te Deum (Kaim-Chor) 30.12.96 Te Deum Meta Hieber (s), Elisabeth Exter (a), U. Schreiber (t), Eduard Schuegraf (bs), Kaim- Chor, Herman Zumpe (Kaim-Saal, 19:00 Uhr, Bruckner Gedaechtnis-Konzert) 13.01.97 B4 Herman Zumpe (4. Symphoniekonzert, Kaim-Saal, 19:00 Uhr, Bruckner Gedaechtnis- Konzert) 20.01.97 B4 Herman Zumpe (5. Symphoniekonzert, Kaim-Saal, 19:30 Uhr, Bruckner Gedaechtnis- Konzert) 04.02.98 B5 Ferdinand Loewe (3. Symphoniekonzert, Kaim-Saal, Deutsche Erstauffuehrung) 01.03.98 B5 Ferdinand Loewe (Wiener Erstauffuehrung, Musikverein, Grosses Saal, 20 Uhr) 10.02.99 B7 Siegmund von Hausegger 17.12.00 B8 Siegmund von Hausegger (Muncher Erstauffuehrung) 13.11.03 B9 Bernhard Stavenhagen (Munchener Erstauffuehrung, Erster moderner Abend) 20.02.05 ? B4, B9 Ferdinand Loewe (Erstes Munchner Anton-Bruckner-Fest, Erstes Abend) 21.02.05 B6, 150. Psalm Ferdinand Loewe (Muenchner Erstauffuehrung, Erstes Muenchner Anton- Bruckner-Fest, Zweites Abend) 19.02.06 B9 Wilhelm Furtwaengler 03.10.07 B5 Alfred Westarp (alias of Egon Victor Frensdorff) Tonhalle (previously called Kaim-Saal) 08.-09.09 Beethoven-Brahms-Bruckner-Zyklus 17.10.10 B1 Ferdinand Loewe 14.11.10 B2 Ferdinand Loewe 21.11.10 B3 Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1890) 09.01.11 B4 Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1889) 30.01.11 B5 Ferdinand Loewe 13.02.11 B6 Ferdinand Loewe 27.02.11 B7 Ferdinand Loewe 06.03.11 B8, 150. Psalm Ferdinand Loewe (Charles Cahier) 10.04.11 B9, Te Deum Ferdinand Loewe 22.01.19 B4 Wilhelm Furtwaengler (6. Ab.-Kz.) 21.01.20 B5 Hans Pfitzner 20.10.20 B7 Siegmund von Hausegger 03.01.21 B9 Werner von Buelow 10.11.21 B00 Andante Frederick Charles Adler (Muenchner Erstauffuehrung. -

Consortium Classicum

Große Kammermusik Samstag 12. Januar 2013, 18 Uhr, Fiskina Fischen Consortium classicum Gunhild Ott, Flöte Andreas Krecher, Violine Pavel Sokolov, Oboe Niklas Schwarz, Viola Manfred Lindner, Klarinette Armin Fromm, Cello Helman Jung, Fagott Jürgen Normann, Kontrabass Jan Schröder, Horn Programm: Louis Spohr Gran Nonetto, F-Dur, op.31 (1819) W. A. Mozart Flötenquartett D-Dur, KV 285 (1777/78) Franz Lachner Nonett F-Dur, (1875) `Hommage à Franz Schubert´ 29 Mit der Grundung des Consortium Classicum betrat vor Darüber hinaus wird die Arbeit des CC durch ein hausei- etwa fünfzig Jahren ein deutsches Kammerensemble die genes Musikarchiv unterstützt, welches exklusiv einen Musikszene, um in variabler Besetzung, neben der selbst- reichhaltigen Bestand an Werken zu Unrecht vergessener verständlichen Pflege des Standardrepertoires auch zahl- Meister des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts beinhaltet. Dieses reiche wiederentdeckte Musikschätze lebendig werden zu Archiv, das seit Jahrzehnten der Grundlagenforschung lassen. Initiator war der inzwischen verstorbene verpflichtet ist, garantiert, daß auch in Zukunft auf CD, Klarinettist Dieter Klöcker, der bis zu zehn Solisten, im Fernsehen und selbstverständlich ganz besonders im Hochschulprofessoren und Stimmfuhrer aus Konzertleben die Breite der künstlerischen Aussagen und Spitzenorchestern um sich scharte und mit ihnen den die Qualität der Ausfuhrungen auf hohem Niveau Ensemblegedanken in einer sehr eigenen und konsequen- gewährleistet ist. ten Form pflegte. Diese Vielfalt von solistischem Können, Ensemblegeist Eine internationale Konzerttätigkeit sowie zahlreiche und Forschung bestätigt den exzeptionellen Rang dieses ehrenvolle Auszeichnungen und Einladungen zu promi- in jeder Hinsicht einzigartigen Ensembles. nenten Festivals, wie den Salzburger Festspielen oder den Festwochen in Wien und Berlin, brachten dem Ensemble Pavel Sokolov, Oboe, lernte ab 1981 bei Sergej Burdukov weltweite Anerkennung. -

Gitlis VIOLIN CONCERTOS Paganini • Hindemith • Bartók • Haubenstock-Ramati RECITAL Brahms • Debussy • Bloch • Wieniawski

SWR T al ap n e i s g i r O 1962 • • –1986D R E E M AST E R Ivry Gitlis VIOLIN CONCERTOS Paganini • Hindemith • Bartók • Haubenstock-Ramati RECITAL Brahms • Debussy • Bloch • Wieniawski Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR Stanislaw Skrowaczewski SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg Hans Rosbaud Orchester des Nationaltheaters 2 CD Mannheim | Wolfgang Rennert CD 1 79:02 bo Henri Wieniawski (1835–1880) Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840) Polonaise für Violine und Klavier Peter Ziegler im Gespräch mit haus“ nannte (kichert), und da war dieser D-Dur op. 4° 4:52 nette kleine Mann, Itzhak Joffé, dessen Fami- Violinkonzert Nr. 2 h-Moll op. 7 26:29 Polonaise for Violin and Piano Ivry Gitlis Violin Concerto in B Minor Op.7 D Major Op.4 lie aus Israel kam. Ich glaube, einer aus seiner 1 I Allegro maestoso 13:11 2 ºwith Daria Horova (piano) PZ: Wann haben Sie das Hindemith-Konzert Familie war General in der israelischen Armee. 3 II Adagio 6:25 Live Recording 31.01.1986 Ettlingen zum ersten Mal gespielt? Wir aßen zusammen zu Mittag und zu Abend, III Rondo. Allegretto moderato IG: Das war ganz verrückt. Ich habe es in elf redeten, und eines Tages sagte er, er reise ab, „La Campanella“ 6:53 CD 2 76:38 oder zwölf Tagen gelernt, so in etwa. Ich konn- zurück nach New York. Er war der Privatsekre- Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) te es nicht auswendig lernen; ich hatte die tär von Marian Anderson und versprach mir, des SWR, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski Klavier- und Violinstimme. -

Rudolf Serkin Papers Ms

Rudolf Serkin papers Ms. Coll. 813 Finding aid prepared by Ben Rosen and Juliette Appold. Last updated on April 03, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2015 June 26 Rudolf Serkin papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 I. Correspondence.................................................................................................................................... 9 II. Performances...................................................................................................................................274 -

G É Za Aa Nd A

AVAILABLE: 2CDs DIETRICH FISCHER-DIESKAU sings Arias by J. C. Bach and J. S. Bach Recordings 1953/54/57/59 CD 94.201 A IDA HAENDEL plays ND A Brahms & Mendelssohn Recordings 1953/55 CD 94.202 ZA SWR Sinfonieorchester É Baden-Baden und Freiburg Ernest Bour | Hans Rosbaud G Eine große Auswahl von über 700 Klassik-CDs Enjoy a huge selection of more than 700 classical und DVDs fi nden Sie unter CDs and DVDs at www.haenssler-classic.com, www.haenssler-classic.de, auch mit Hör- including listening samples, download and artist GÉZA ANDA plays beispielen, Download-Möglichkeiten und Künst- related information. You may as well order our lerinformationen. Gerne können Sie auch printed catalogue, order no.: 955.410. unseren Gesamtkatalog anfordern unter der E-mail contact: [email protected] CHOPIN, RACHMANINOV, SCHUMANN, BRAHMS Bestellnummer 955.410. E-Mail-Kontakt: [email protected] HISTORICAL RECORDINGS 1952/53/58/63 HISTORIC CD 1 CD 2 Géza Anda und der SWR Anda erwarb sein eigenes Rüstzeug an der von Franz Liszt gegründeten und nach ihm benannten Budapester Musikakademie, FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN (1810-1849) ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) Klavierkonzerte von Schumann, der herausragende Musikerpersönlichkei- Konzert für Klavier und Orchester Nr. 1 Konzert für Klavier und Orchester a-Moll Chopin, Rachmaninow und Brahms ten wie Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, Sandor e-Moll op. 11 | Concerto for Piano and op. 54 | Concerto for Piano and Veress, György Ligeti und György Kurtág Orchestra No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 38:40 Orchestra in A Minor, Op. 54 30:55 Géza Anda (Budapest 1921–Zürich 1976) als Schüler wie Lehrer angehörten.