ENGLISH Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 39176 January 2007 Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement Prepared by the Road Transport Service Department for the Asian Development Bank. The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. 2 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 2 January 2007) Currency Unit – Azerbaijan New Manat/s (AZM) AZM1.00 = $1.14 $1.00 = AZM0.87 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DRMU – District Road Maintenance Unit EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESS – Ecology and Safety Sector IEE – initial environmental examination MENR – Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources MFF – multitranche financing facility NOx – nitrogen oxides PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance ROW – right-of-way RRI – Rhein Ruhr International RTSD – Road Transport Service Department SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SOx – sulphur oxides TERA – TERA International Group, Inc. UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WHO – World Health Organization WEIGHTS AND MEASURES C – centigrade m2 – square meter mm – millimeter vpd – vehicles per day CONTENTS MAP I. Introduction 1 II. Description of the Project 3 IIII. Description of the Environment 11 A. Physical Resources 11 B. Ecological and Biological Environment 13 C. -

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe for Suggestions and Comments

Unofficial translation* SUMMARY REPORT UNDER THE PROTOCOL ON WATER AND HEALTH THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN Part One General aspects 1. Were targets and target dates established in your country in accordance with article 6 of the Protocol? Please provide detailed information on the target areas in Part Three. YES ☐ NO ☐ IN PROGRESS If targets have been revised, please provide details here. 2. Were they published and, if so, how? Please explain whether the targets and target dates were published, made available to the public (e.g. online, official publication, media) and communicated to the secretariat. The draft document on target setting was presented in December 2015 to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and United Nations Economic Commission for Europe for suggestions and comments. After the draft document review, its discussion with the public is planned. To get suggestions and comments it will be made available on the website of Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan Republic and Ministry of Health of Azerbaijan Republic. Azerbaijan Republic ratified the Protocol on Water and Health in 2012 and as a Protocol Party participated in two cycles of the previous reporting. At present the targets project is prepared and sent to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. It should be noted that the seminar to support the progress of setting targets under the Protocol on Water and Health was held in Baku on 29 September 2015. More than 40 representatives of different ministries and agencies, responsible for water and health issues, participated in it. -

General Assembly Security Council Seventy-Fifth Session Seventy-Fifth Year Agenda Items 34, 71 and 135

United Nations A/75/356–S/2020/947 General Assembly Distr.: General 28 September 2020 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Seventy-fifth session Seventy-fifth year Agenda items 34, 71 and 135 Prevention of armed conflict Right of peoples to self-determination The responsibility to protect and the prevention of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity Letter dated 27 September 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General I have the honour to enclose herewith a letter from Zohrab Mnatsakanyan, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia, regarding the large-scale military offensive launched by the Azerbaijani armed forces against Nagorno - Karabakh on 27 September 2020 (see annex). I kindly request that the present letter and its annex be circulated as a document of the General Assembly, under agenda items 34, 71 and 135, and of the Security Council. (Signed) Mher Margaryan Ambassador Permanent Representative 20-12655 (E) 011020 *2012655* A/75/356 S/2020/947 Annex to the letter dated 27 September 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Excellency, On 27 September, Azerbaijani armed forces launched large-scale airborne, missile, and land attack along the entire line of contact between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan, targeting civilian settlements, infrastructure, and schools, including in the capital city of Stepanakert. There were also casualties among civilians: a woman and a child were killed during the very first strikes. The aggression was well-prepared and any reference by the Azerbaijani side to an alleged “counterattack” is utterly deceptive. -

Quaternary Science Reviews 222 (2019) 105895

Quaternary Science Reviews 222 (2019) 105895 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Magneto-biostratigraphic age constraints on the palaeoenvironmental evolution of the South Caspian basin during the Early-Middle Pleistocene (Kura basin, Azerbaijan) * Sergei Lazarev a, , Elisabeth L. Jorissen a, Sabrina van de Velde b, Lea Rausch c, Marius Stoica c, Frank P. Wesselingh b, Christiaan G.C. Van Baak d, Tamara A. Yanina e, Elmira Aliyeva f, Wout Krijgsman a a Paleomagnetic Laboratory «Fort Hoofddijk», Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 17, 3584CD, Utrecht, the Netherlands b Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300RA, Leiden, the Netherlands c Department of Geology, Faculty of Geology and Geophysics, Bucharest University, Bǎlcescu Bd. 1, 010041, Bucharest, Romania d CASP, West Building, Madingley Rise, Madingley Road, CB3 0UD, Cambridge, United Kingdom e M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Geographical Faculty, Leninskiye Gory, 119992, Moscow, Russia f Institute of Geology ANAS, H. Javid av., 29A, 1143, Baku, Azerbaijan article info abstract Article history: The sedimentary record of the Caspian Basin is an exceptional archive for the palaeoenvironmental, Received 21 January 2019 palaeoclimatic and biodiversity changes of continental Eurasia. During the Pliocene-Pleistocene, the Received in revised form Caspian Basin was mostly isolated but experienced large lake level fluctuations and short episodes of 19 August 2019 connection with the open ocean as well as the Black Sea Basin. A series of turnover events shaped a Accepted 21 August 2019 faunal record that forms the backbone of the Caspian geological time scale. The precise ages of these Available online 14 September 2019 events are still highly debated, mostly due to the lack of well-dated sections. -

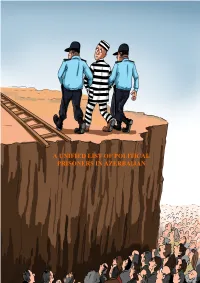

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

Agricultural Support to Azerbaijan Project (ASAP) Implemented by CNFA

AGRICULTUR AL SUPPORT TO AZERBAIJAN PROJECT (ASAP) YEAR FIVE WORK PLAN Project Year 5: October 1, 2018-September 17, 2019 Prepared for review by the United States Agency for International Development under USAID Contract No. AID-112- C-14-00001 , Agricultural Support to Azerbaijan Project (ASAP) implemented by CNFA. Submitted to USAID on September 10, 2018 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 4 II. Project Overview ........................................................................................................... 5 III. Year 4 Accomplishments .............................................................................................. 6 a. Hazelnut Value Chain .................................................................................................... 7 b. Orchard Value Chain ..................................................................................................... 8 c. Pomegranate Value Chain ........................................................................................... 10 d. Vegetable Value Chain ................................................................................................ 12 e. Berry Value Chain ....................................................................................................... 13 f. Access to Finance ........................................................................................................ 14 g. Food Safety and Quality ............................................................................................. -

1 S PIP CQUI – Azer ELINE SITIO Rbai

SOUTH CAUCASUS PIPELINE EXPANSION PROJECT GUIDE TO LAND ACCQUISITION AND COMPENSATION – Azerbaijan, AMENDMENT 1 This is an amendment to the Guide to Land Acquisition and Compensation (GLAC) prepared for the South Caucasuus Pipeline Expansion (SCPX) project activities in Azerbaijan. This document updates the version of the GLAC issued in 2015 to account for updates to the land rental and crop compensation rates and is applicable to new land acquisiition undertaken from April 1st, 2017 onwards. It was prepared by SCP Co. based on inputs from independent consultants specialised in land acquisition. The equivalent information in the GLAC, 2015 are updated by the information below. All other information as it relates to land acquisition and compensation within the GLAC, 2015 remains unchanged and applies to all new SCPX land acquisition and compensation activities. This Amendment does not apply to existing lease agreements or user agreements. This document is also available on the Reports and Publications page at www.bp.com/caspian. This document is presented in English and Azerbaijani languages. In the event of any conflict or disagreement in interpretation of any provisions between tthese different language versions, the English version shall bee the definitive, prevailing document. Inquiries in relation to this document can be addressed to the following address or telephone numbeer: SCP Co. BP Xazar Centre Port Baku 153 Neftchilar Avenue AZ1010 Baku Azerbaijan Tel: (+994) 12 599 3000 (Switchboard) 1 APPENDIX 1 – PROJECT COMPENSATION RATES -

Azerbaijan: Floods

DREF operation n° MDRAZ002 AZERBAIJAN: GLIDE n° FL-2010-000089-AZE 18 May, 2010 FLOODS The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 171,321 (USD 150,953 or EUR 122,201) has been allocated from the International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the National Society in delivering immediate assistance to some 2,195 beneficiaries. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: On 4 May 2010 heavy rains caused flooding in 40 districts surrounding the Kur (Kura), Azerbaijan's main river. Three people lost their lives and the total number of affected people in seven regions is around 70,000. Only in Sabirabad district and its 11 villages more than 24,000 people have been affected. Some 20,000 houses have been flooded, 300 of them ruined, and more than 2,000 houses are under threat to be destroyed. Around 50,000 hectares of cultivated land and pasture are under water. The Azerbaijan Red Crescent aims to Floods in Sabirabad region with many houses under water provide food and non-food items to 2,195 persons and totally destroyed. Photo: Azerbaijan Red Crescent. (400 families) evacuated from Sabirabad villages and temporary placed in schools, administrative buildings and camps of Shirvan town to help them cope with the consequences of the disaster. -

BP in Azerbaijan Sustainability Report 2010

BP in Azerbaijan Sustainability Report 2010 www.bp.com/caspian/sr 2 Introduction by the president of the BP Azerbaijan-Georgia-Turkey region 3 This is BP in Azerbaijan / 17 How we operate / 29 Safety and health / 35 Environment / 43 Society 52 Five-year performance data / 53 EITI reported data / 55 Report process and feedback Scope of report The scope of this report covers the calendar year ending 31 December 2010. All dollar amounts are in US dollars. Unless otherwise specified, the text does not distinguish between the operations and activities of BP p.l.c. and those of its subsidiaries and affiliates. References in this report to ‘us’, ‘we’ and ‘our’ relate to BP in Azerbaijan unless otherwise stated. In this report when we refer to BP in Azerbaijan we refer to our operations in Azerbaijan only. If we refer to BP AGT we are referring to our activities in Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. Specific references to ‘BP’ and the ‘BP group’ mean BP p.l.c., its subsidiaries and affiliates. Front cover image Challenge drilling engineer Aysel Javadova at Deepwater Gunashli platform Cautionary statement The BP in Azerbaijan Sustainability Report 2010 contains certain forward-looking statements relating, in particular, to recoverable volumes and resources, capital, operating and other expenditures, and future projects. Actual results may differ from those expressed in such statements depending on a variety of factors including supply and demand developments, pricing and operational issues and political, legal, fiscal, commercial and social circumstances. Group sustainability reporting bp.com/sustainability What’s inside? The 2010 BP in Azerbaijan Sustainability Report covers our business 2 Introduction by the president of the BP performance, environmental record and wider role in Azerbaijan Azerbaijan-Georgia- during 2010. -

Azerbaijan Health System Review

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 12 No. 3 2010 Azerbaijan Health system review Fuad Ibrahimov • Aybaniz Ibrahimova Jenni Kehler • Erica Richardson Erica Richardson (Editor) and Martin McKee (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT profile Editorial Board Editor in chief Elias Mossialos, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin Technical University, Germany Josep Figueras, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom Richard Saltman, Emory University, United States Editorial team Sara Allin, University of Toronto, Canada Matthew Gaskins, Berlin Technical University, Germany Cristina Hernández-Quevedo, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Maresso, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies David McDaid, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sherry Merkur, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Philipa Mladovsky, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Erica Richardson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sarah Thomson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Ewout van Ginneken, Berlin University of Technology, Germany International advisory board Tit Albreht, Institute of Public Health, Slovenia Carlos Alvarez-Dardet Díaz, University of Alicante, Spain Rifat Atun, Global Fund, Switzerland Johan Calltorp, Nordic School of Public Health, -

Of the Republic of Azerbaijan

COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (OMBUDSMAN) OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ANNUAL REPORT ON PROVISION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS IN THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN 2011 (SUMMARY) Baku – 2012 1 Foreword The main aim of the report is to evaluate the state of ensuring human and civil rights and freedoms in the country, to analyze the situation of important problems on human rights revealed in 2011, as well as to provide the information on activities conducted by the Commissioner for Human Rights (Ombudsman) of the Republic of Azerbaijan for the restoration of violated human rights, protection of human rights and prevention of their infringement The report was prepared on the basis of appeals, petitions, proposals and complaints; different cases, problems and challenges disclosed during the visits of the Commissioner and staff members of the Institute to penitentiaries, investigatory isolators, temporary detention places, military units, orphanages, boarding schools, settlements of the refugees and IDPs, healthcare and social protection facilities, meetings with population in regions and investigations carried out there; official responses and attitudes of state agencies and authorities; proposals and recommendations submitted to state bodies; materials of national and international seminars and conferences dedicated to human rights; works implemented within the framework of the cooperation with non-governmental organizations; as well as of the information provided by the mass media. The report reflects the activities of the Commissioner in the area of the protection of human rights and freedoms, educational and awareness-raising events regarding the given sphere, the organization of scientific-analytical work, public relations, issues of international cooperation, as well as outcomes and recommendations.