Diplomarbeit / Diploma Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unseen Poetry Preparation Anthology

Unseen Poetry Preparation Anthology The Pearson Edexcel AS and A level English Literature Unseen Poetry Preparation Anthology can be used to prepare for Component 3 of your assessment Pearson Edexcel GCE in English Literature Approaching Contemporary Unseen Poetry: An Anthology of poems and resources For use with: GCE English Literature A level (9ET0) Component 3 Published by Pearson Education Limited, a company incorporated in England and Wales, having its registered office at Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex, CM20 2JE. Registered company number: 872828 Edexcel is a registered trade mark of Edexcel Limited © Pearson Education Limited 2014 First published 2014 17 16 15 14 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 9781446913505 Copyright notice All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS (www.cla.co.uk). Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission should be addressed to the publisher. See page 65 for acknowledgements. Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 How to approach -

Spotlight the Newsletter for English Faculty Alumni

Spotlight The newsletter for English Faculty Alumni July 2020 | Issue 6 This newsletter is coming from our newly virtual Faculty. We closed the doors to the St Cross building on 24 March 2020, and have since been finding new and creative ways to work with our students until we reopen in Michaelmas Term. Despite the tumultuous and unpredictable nature of life in a world with COVID- 19, we've managed to navigate new technologies which have enabled us to continue teaching and research from afar. Thanks to the support of TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities) we've even managed to host our first ever online Professor of Poetry lecture with Alice Oswald, plus take part in numerous other online events including: The Social Life of Books, Invalids on the Move, and Shakespeare and the Plague (hosted by the University as part of Oxford at Home). These are all still available to watch (click on the links to be taken to the recordings). We also participated in the University’s Online Open Days at the beginning of July with video recordings by staff and students and live Q&As. Members of the Faculty have secured funding for projects which offer a response to the repercussions of COVID-19: Professor Sally Shuttleworth for Contagion Cabaret, and Dr Stuart Lee for Lockdown 2020. We were also delighted to be recognised with an Athena Swan Bronze Award in May. The award recognises commitment to the advancement of gender equality in higher education and research institutions. Black Lives Matter has seen us look to our teaching, syllabi, and recruitment and retention of staff to see how we can positively effect change in our Faculty. -

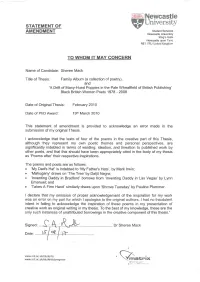

Mack, S. 2010.Pdf

Family Album (a collection of poetry), and lA Drift of Many-Hued Poppies in the Pale Wheatfield of British Publishing': Black British Women Poets 1978 - 2008 Sheree Mack A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Newcastle University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2010 NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ---------------------------- 208 30279 h Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Family Album, a collection of poetry 1 The Voice of the Draft 49 Dissertation: 'A Drift of Many-Hued Poppies in the Pale Wheatfield of 54 British Publishing': Black British Women Poets 1978 - 2008 Introduction 55 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 1 72 Chapter One: Introducing Black Women Writers to Britain 76 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 2 102 Chapter Two: Black Women Insist On Their Own Space 105 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 3 148 Chapter Three: Medusa Black, Red, White and Blue 151 The Voice of the Tradition 183 Chapter Four: Conclusion 189 Linking Piece: 'she tries her tongue' 4 194 Select Bibliography 197 Abstract The thesis comprises a collection of poems, a dissertation and a series of linking pieces. Family Album is a portfolio of poems concerning the themes of genealogy, history and family. It also explores the use of devices such as voice, the visual, the body and place as an exploration of identity. Family Album includes family elegies, narrative poems and commissioned work. The dissertation represents the first study of length about black women's poetry in Britain. Dealing with a historical tradition dating back to the eighteenth century, this thesis focuses on a recent selection of black women poets since the late 1970s. -

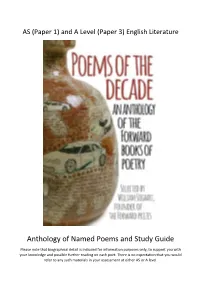

Anthology of Named Poems and Study Guide

AS (Paper 1) and A Level (Paper 3) English Literature Anthology of Named Poems and Study Guide Please note that biographical detail is included for information purposes only, to support you with your knowledge and possible further reading on each poet. There is no expectation that you would refer to any such materials in your assessment at either AS or A level. Contents Page in this Page in Poem Poet booklet Anthology Eat Me Patience Agbabi 3 3 Chainsaw Versus the Pampas Simon Armitage 7 6 Grass Material Ros Barber 11 10 Inheritance Eavan Boland 17 22 A Leisure Centre is Also a Sue Boyle 21 23 Temple of Learning History John Burnside 25 25 The War Correspondent Ciaran Carson 30 29 An Easy Passage Julia Copus 36 37 The Deliverer Tishani Doshi 41 43 The Map Woman Carol Ann Duffy 46 47 The Lammas Hireling Ian Duhig 53 51 To My Nine-Year-Old Self Helen Dunmore 58 52 A Minor Role U A Fanthorpe 62 57 The Gun Vicki Feaver 66 62 The Furthest Distances I’ve Leontia Flynn 70 64 Travelled Giuseppe Roderick Ford 74 66 Out of the Bag Seamus Heaney 78 81 Effects Alan Jenkins 85 92 The Fox in the National Robert Minhinnick 90 121 Museum of Wales Genetics Sinéad Morrissey 95 125 From the Journal of a Andrew Motion 99 127 Disappointed Man Look We Have Coming to Daljit Nagra 104 129 Dover! Fantasia on a Theme of James Sean O’Brien 108 130 Wright Please Hold Ciaran O’Driscoll 112 132 You, Shiva, and My Mum Ruth Padel 117 140 Song George Szirtes 122 168 On Her Blindness Adam Thorpe 126 170 Ode on a Grayson Perry Urn Tim Turnbull 131 172 Sample Assessment Questions 137 Sample Planning Diagrams 138 Assessment Grid 143 2 Patience Agbabi, ‘Eat Me’ Biography Patience Agbabi (b. -

Feminist Revisions of the Sonnet in the Works of Patience Agbabi and Sophie Hannah

ARTICLES WIELAND SCHWANEBECK Feminist Revisions of the Sonnet in the Works of Patience Agbabi and Sophie Hannah Without a doubt, the sonnet is the most well-known and "the longest-lived of all poetic forms" (Spiller 1992, 2). This is certainly true of the Anglophone world, where the sonnet has never completely gone out of fashion since the Shakespearean age and has, for the most part, managed to retain its trademark form of fourteen lines, as well as a few characteristic rhyme schemes and stanzaic arrangements. Yet it has also proven adaptable enough to accommodate rather diverse themes and agendas: The sonnet is often aimed at a desired and unattainable addressee and adopts the view- point of an amorous lyrical speaker. In other cases, it has mourned the passing of time and offered witty insight into current world events, lewd proposals, outstanding individuals, or even, in a famous example by Gilbert Keith Chesterton, the enduring quality of Stilton cheese ("Sonnet to a Stilton Cheese," [1912] 1957). So popular and indestructible is the sonnet that it even manages to absorb critique to form the 'anti- sonnet' as a distinct sub-genre. Authors as diverse as John Keats ("If by Dull Rhymes Our English Must Be Chained," [1819] 2001), Stephen Fry ("I Wrote a Bad Petrarchan Sonnet Once," 2005), or Robert Gernhardt ("Materialien zu einer Kritik der bekanntesten Gedichtform italienischen Ursprungs," 1981) have contributed humorous and memorable sonnets of this variety; Billy Collins's "Sonnet" (1999) simply counts down the lines ("All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now, / and after this next one just a dozen") until the poet can "take off those crazy medieval tights" and "come at last to bed" (Collins [1999] 2001, 277). -

January - June 2019 FICTION the Shadow King MAAZA MENGISTE

January - June 2019 FICTION The Shadow King MAAZA MENGISTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR RELEASE DATE: 5 DECEMBER 2019 Export/Airside - Export/Airside/Ireland PAPERBACK 9781838851392 £14.99 January - June 2019 Fiction 02 The Island Child MOLLY AITKEN A rich, haunting and deeply moving novel about the power and the danger in a mother’s love, from one of the most exciting new voices in Irish fiction Twenty years ago, Oona left the island of Inis for the very first time. A wind-blasted rock of fishing boats and turf fires, where the only book was the Bible and girls stayed in their homes until they became mothers themselves, the island was a gift for some, a prison for others. Oona was barely more than a girl, but promised herself she would leave the tall tales behind and never return. The Island Child tells two stories: of the girl who grew up watching births and betrayals, storms and secrets, and of the adult Oona, desperate to find a second chance, only to discover she can never completely escape. As the strands of Oona’s life come RELEASE DATE: 30 JANUARY 2020 together, in blood and marriage and motherhood, she must accept the price we pay when we love what is never truly ours … HARDBACK 9781786898333 Rich, haunting and rooted in Irish folklore, The Island Child is a £14.99 spellbinding debut novel about identity and motherhood, freedom and fate, and the healing power of stories. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Molly Aitken was born in Scotland in 1991 and brought up in Ireland. She studied Literature and Classics at Galway University and has an MA in Creative Writing from Bath Spa. -

UNTITLED Catching NOVEL by Alan Parks (World English) Otherup with Rights: Him

Canongate is an independent publisher: since 1973 we’ve worked to unearth and amplify the most vital, exciting voices we can find, wherever they come from, and we’ve published all kinds of books – thoughtful, upsetting, gripping, beatific, vulgar, chaste, unrepentant, life-changing . Along the way there have been landmarks of fiction – including Alasdair Gray’s masterpiece Lanark, and Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, the best-ever-selling Booker winner – and non-fiction too. We’ve published an American president and a Guantanamo detainee; we’ve campaigned for causes we believe in and fought court cases to get our authors heard. And twice we’ve won Publisher of the Year. We’re still fiercely independent, and we’re as committed to unorthodox and innovative publishing as ever. Andrea Joyce, Rights Director: [email protected] Jessica Neale, Senior Rights Manager: [email protected] Caroline Clarke, Rights Manager: [email protected] Bethany Ferguson, Rights Assistant: [email protected] Canongate 14 High Street Edinburgh EH1 1TE UK Tel: +44 (0) 131 557 5111 For more information on thecanongate.co.uk Publishing Scotland Translation Fund, visit: http://bit.ly/translation-support For more information on the Publishing Scotland Fellowship, visit: https://bit.ly/2MNSNjb Author Photo Credits: Tola Rotimi Abraham: Carole Cassier; Peter Ackroyd: Charles Hopkinson; Patience Agbabi: Lyndon Douglas; Molly Aitken: Christy Ku; Tahmima Anam: Abeer Y Hoque; Priya Basil: Suhrkamp Verlag; Janie Brown: Genevieve Russell, Story Portrait Media; Melanie Challenger: Alice Little; Kerri ni Dochartaigh: Wendy Barrett; Will Eaves: John Cairns; Gavin Francis: Chris Austin; Salena Godden: Simon Booth; Emily Gravett: Mik Gravett; Steven Hall: Jerry Bauer; Claudia Hammond: Ian Skelton; Matt Haig: Kan Lailey; Richard Holloway: Colin Hattersley-Smith; M. -

Fairytale Theory and Explorations of Gender Stereotypes in Post-1970S Rapunzel Adaptations

Fairytale Theory and Explorations of Gender Stereotypes in Post-1970s Rapunzel Adaptations GARY FORSTER Submitted for the degree of PhD De Montfort University June 2015 Fairytale Theory and Explorations of Gender Stereotypes in Post-1970s Rapunzel Adaptations Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………. ii Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… iii List of Figures…………………………………………………………………….. iv 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 01 2. The Grimm ‘Rapunzel’ (1812-1857)…………………………………………… 33 3. Rapunzel Poems………………………………………………………………… 46 Anne Sexton: ‗Rapunzel‘ (1970)………………………………………………… 48 Olga Broumas: ‗Rapunzel‘ (1977)……………………………………………….. 59 Liz Lochhead: ‗Rapunzstiltskin‘ (1981)…………………………………………. 65 Patience Agbabi: ‗RAPunzel‘ (1995)……………………………………………. 72 4. Rapunzel Short Stories, Novels, and Graphic Novels………………………… 84 A. Claffey, R. Conroy, L. Kavanagh, M.P. Keane, C. MacConville, S. Russell: ‗Rapunzel‘s Revenge‘ (1985)…………………………………………………… 84 Emma Donoghue: ‗The Tale of the Hair‘ (1997)……………………………….... 88 Marina Warner: ‗The Difference in the Dose: A Story After ‗Rapunzel‘‘ (2010) 105 Donna Jo Napoli: Zel (1996)……………………………………………………... 116 Shannon, Dean, and Nathan Hale: Rapunzel‘s Revenge (2008)…………………. 125 5. Film Rapunzels………………………………………………………………….. 141 Rapunzel Let Down Your Hair (1978)…………………………………………… 142 Barbie as Rapunzel (2002)……………………………………………………….. 152 Shrek the Third (2007)…………………………………………………………… 157 Tangled (2010)…………………………………………………………………… 162 Into the Woods (2014)……………………………………………………………. 176 6. Commercial Hairy-Tales………………………………………………………. -

Introducing Ten Inspiring UK Women Writers Let Elif Shafak Offer You a Guide to Modern British Writing

Introducing ten inspiring UK women writers Let Elif Shafak offer you a guide to modern British writing Ideas for your next festival, reading programme, or inspiration for your students Contents Good writing knows no borders 1nta 3 Extraordinary times call for extraordinary 4cts women Patience Agbabi 5 Lucy Caldwell 6 Gillian Clarke 7 Bernardine Evaristo 8 Jessie Greengrass 9 Charlotte Higgins 10 Kapka Kassabova 11 Sara Maitland 12 Denise Mina 13 Evie Wyld 14 Bidisha on Elif Shafak’s selection 15 Podcast: Elif Shafak and Bidisha in 18 conversation In the press 21 Coming soon 23 The International Literature Showcase is a partnership between the National Centre for Writing and British Council, with support from Arts Council England. Your guide to modern British writing... Looking to book inspiring writers for your next festival? Want to introduce your students to exciting new writing from the UK? The International Literature Showcase is a partnership between the National Centre for Writing and British Council. It aims to showcase amazing writers based in the UK to programmers, publishers and teachers of literature in English around the world. To do so, we have invited six leading writers to each curate a showcase of themed writing, starting with Elif Shafak’s choice of ten of the most exciting women writers working in the UK today. Following the high-profile launch of Elif’s showcase at London Book Fair earlier this month, we will in August reveal Val McDermid’s choice of ten lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI) writers. In October, Jackie Kay will choose the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) writers working in the UK who most excite her. -

The NAWE Conference in the Year of the Shakespeare 400 Celebrations

The NAWE Conference in the year of the Shakespeare 400 celebrations Macbeth , 2016, dir. Kit Monkman Exclusive discussion with the director, Saturday, 12 November, 2pm with special guests: Patience Agbabi and Kit de Waal Stratford Manor 11-13 November 2016 Introduction Welcome to the NAWE Conference 2016! We’re thrilled to be here in Stratford-upon-Avon in the year of the Shakespeare 400 celebrations, and delighted to offer a rich range of presentations, talks, and workshops. With the Shakespeare connection in mind, we are particularly pleased to offer an exclusive screening of excerpts from the very latest film of Macbeth , with director, Kit Monkman, in conversation with Judith Buchanan, one of the world’s leading authorities in Shakespeare on film. For the evenings, our speakers are poet Patience Agbabi and novelist Kit de Waal, both of whom have a passionate interest in creative writing and education. Each reading will be followed by a Q&A and a book signing, so there will be plenty of opportunities to ask questions about writing and practice. Our programme is split into six loose strands with a string of workshops focusing on craft. Anyone wishing to spend the weekend writing won’t be disappointed, and if you’re looking for material, two unique falconry sessions* should offer some inspiration (early booking essential). We’re also welcoming the very first conference session from our new PhD Network, as well as a consultation for the new Paper Nations Young Creative Writer Award (funded by Arts Council England). NAWE staff and Management Committee are on hand to guide you through the weekend, while colleagues Clare Mallorie and Gill Greaves are available to help with any practical or technical questions. -

Poesía Contemporánea De Inmigración Caribeña Y Africana En El Reino Unido

Tesis doctoral Tomo I Poesía contemporánea de inmigración caribeña y africana en el Reino Unido Ana Belén Muñoz Jiménez Licenciada en Filosofía y Letras (secciones Filología Inglesa y Filología Hispánica) por la Universidad de Málaga UNED Departamento de Filologías Extranjeras y sus Lingüísticas Facultad de Filología Año 2011 Departamento de Filologías Extranjeras y sus Lingüísticas Facultad de Filología UNED Poesía contemporánea de inmigración caribeña y africana en el Reino Unido Tomo I Ana Belén Muñoz Jiménez Licenciada en Filosofía y Letras (secciones Filología Inglesa y Filología Hispánica) por la Universidad de Málaga Directora de la tesis Dra. Ángeles de la Concha Muñoz Quisiera agradecer a mi directora, la doctora Ángeles de la Concha Muñoz, su inestimable ayuda a lo largo de la elaboración de la tesis, así como su cariño, comprensión y paciencia. Asimismo, agradezco el apoyo que me ha brindado mi familia, en especial, mi marido y mi madre, sin los cuales esta tesis no habría visto la luz. A Alicia por su comprensión y sus sabios consejos. A mis hijos, Rafael y Lucrecia, la razón de mi existencia. A todas las madres trabajadoras e investigadoras que se niegan a resignar su corazón a “lo que quise hacer y no pude”. Índice Introducción I. Poscolonialismo 1 I.1. Orígenes y desarrollo del concepto poscolonial 1 I.2. Intersecciones discursivas con el poscolonialismo 17 I.3. Fundamentos teóricos del poscolonialismo: Edward W. Said, Homi Bhabha y Gayatri Chakravorti Spivak 33 I.3.1. Edward W. Said 33 I.3.2. Homi Bhabha 44 I.3.3. Gayatri Chakravorti Spivak 58 II. -

Contemporary Black British Literature: an Introduction for Students

Contemporary Black British Literature: An Introduction for Students Contemporary Black British Literature: An Introduction for Students Contents Introduction 3 Historical context 5 Introductions to selected prose Incomparable World, S.I. Martin recommended by Dr Leila Kamali 9 NW, Zadie Smith recommended by Dr Malachi McIntosh 10 Strange Music, Laura Fish recommended by Dr Deirdre Osborne 11 Trumpet, Jackie Kay recommended by Heather Marks 12 Introductions to selected drama Fallout, Roy Williams recommended by Dr Deirdre Osborne 13 nut, debbie tucker green recommended by Dr Valerie Kaneko-Lucas 14 Something Dark, Lemn Sissay recommended by Dr Fiona Peters 15 The Story of M, SuAndi recommended by Dr Elaine Aston 16 Introductions to selected poetry Ship Shape, Dorothea Smartt recommended by Dr Suzanne Scafe 17 Telling Tales, Patience Agbabi recommended by Nazmia Jamal 18 The Rose of Toulouse, Fred D’Aguiar recommended by Dr Abigail Ward 19 Too Black, Too Strong, Benjamin Zephaniah recommended by Kadija Sesay 20 Bibliography 21 © Pearson 2017 2 Contemporary Black British Literature: An Introduction for Students Introduction Why have we produced a guide to Contemporary Black British Literature? Think about what you understand by the idea of our English literary heritage. Whose names and faces come to mind when you hear these terms? Shakespeare? Dickens? Keats? Whichever authors you picture as stalwarts of the literary canon, do they have any physical characteristics in common? Are they men? Are they white? Are they dead? The answer may not always be yes to all of these questions, but we would be willing to bet that it is more often than it is not.