Defamation in Singapore Report to to Lawyers' Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

The Decline of Oral Advocacy Opportunities: Concerns and Implications

Published on 6 September 2018 THE DECLINE OF ORAL ADVOCACY OPPORTUNITIES: CONCERNS AND IMPLICATIONS [2018] SAL Prac 1 Singapore has produced a steady stream of illustrious and highly accomplished advocates over the decades. Without a doubt, these advocates have lifted and contributed to the prominence and reputation of the profession’s ability to deliver dispute resolution services of the highest quality. However, the conditions in which these advocates acquired, practised and honed their advocacy craft are very different from those present today. One trend stands out, in particular: the decline of oral advocacy opportunities across the profession as a whole. This is no trifling matter. The profession has a moral duty, if not a commercial imperative, to apply itself to addressing this phenomenon. Nicholas POON* LLB (Singapore Management University); Director, Breakpoint LLC; Advocate and Solicitor, Supreme Court of Singapore. I. Introduction 1 Effective oral advocacy is the bedrock of dispute resolution.1 It is also indisputable that effective oral advocacy is the product of training and experience. An effective advocate is forged in the charged atmosphere of courtrooms and arbitration chambers. An effective oral advocate does not become one by dint of age. 2 There is a common perception that sustained opportunities for oral advocacy in Singapore, especially for junior lawyers, are on the decline. This commentary suggests * This commentary reflects the author’s personal opinion. The author would like to thank the editors of the SAL Practitioner, as well as Thio Shen Yi SC and Paul Tan for reading through earlier drafts and offering their thoughtful insights. 1 Throughout this piece, any reference to “litigation” is a reference to contentious dispute resolution practice, including but not limited to court and arbitration proceedings, unless otherwise stated. -

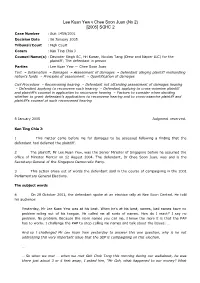

Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan (No 2)

Lee Kuan Yew v Chee Soon Juan (No 2) [2005] SGHC 2 Case Number : Suit 1459/2001 Decision Date : 06 January 2005 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Hri Kumar, Nicolas Tang (Drew and Napier LLC) for the plaintiff; The defendant in person Parties : Lee Kuan Yew — Chee Soon Juan Tort – Defamation – Damages – Assessment of damages – Defendant alleging plaintiff mishandling nation's funds – Principles of assessment – Quantification of damages Civil Procedure – Reconvening hearing – Defendant not attending assessment of damages hearing – Defendant applying to reconvene such hearing – Defendant applying to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel in application to reconvene hearing – Factors to consider when deciding whether to grant defendant's applications to reconvene hearing and to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel at such reconvened hearing 6 January 2005 Judgment reserved. Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 This matter came before me for damages to be assessed following a finding that the defendant had defamed the plaintiff. 2 The plaintiff, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, was the Senior Minister of Singapore before he assumed the office of Minister Mentor on 12 August 2004. The defendant, Dr Chee Soon Juan, was and is the Secretary-General of the Singapore Democratic Party. 3 This action arose out of words the defendant said in the course of campaigning in the 2001 Parliamentary General Elections. The subject words 4 On 28 October 2001, the defendant spoke at an election rally at Nee Soon Central. He told his audience: Yesterday, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was at his best. -

Constitutional Documents of All Tcountries in Southeast Asia As of December 2007, As Well As the ASEAN Charter (Vol

his three volume publication includes the constitutional documents of all Tcountries in Southeast Asia as of December 2007, as well as the ASEAN Charter (Vol. I), reports on the national constitutions (Vol. II), and a collection of papers on cross-cutting issues (Vol. III) which were mostly presented at a conference at the end of March 2008. This collection of Constitutional documents and analytical papers provides the reader with a comprehensive insight into the development of Constitutionalism in Southeast Asia. Some of the constitutions have until now not been publicly available in an up to date English language version. But apart from this, it is the first printed edition ever with ten Southeast Asian constitutions next to each other which makes comparative studies much easier. The country reports provide readers with up to date overviews on the different constitutional systems. In these reports, a common structure is used to enable comparisons in the analytical part as well. References and recommendations for further reading will facilitate additional research. Some of these reports are the first ever systematic analysis of those respective constitutions, while others draw on substantial literature on those constitutions. The contributions on selected issues highlight specific topics and cross-cutting issues in more depth. Although not all timely issues can be addressed in such publication, they indicate the range of questions facing the emerging constitutionalism within this fascinating region. CONSTITUTIONALISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Volume 2 Reports on National Constitutions (c) Copyright 2008 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Editors Clauspeter Hill Jőrg Menzel Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 Tel: +65 6227 2001 Fax: +65 6227 2007 All rights reserved. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

![Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8008/jeyaretnam-joshua-benjamin-v-lee-kuan-yew-2001-1248008.webp)

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin v Lee Kuan Yew [2001] SGCA 55 Case Number : CA 600023/2001 Decision Date : 22 August 2001 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; L P Thean JA Counsel Name(s) : Appellant in person; Davinder Singh SC and Hri Kumar (Drew & Napier LLC) for the respondent Parties : Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin — Lee Kuan Yew Civil Procedure – Striking out – Dismissal of action for want of prosecution – Principles applicable – Inordinate and inexcusable delay – Respondent's delay of over two years without reason or explanation – Whether delay amounts to intentional and contumelious default – Prejudice by reason of delay – Whether unavailability of services of particular Queen's Counsel amounts to prejudice – Whether inordinate and inexcusable delay amounts to abuse of court process – Limitation period yet to expire – Whether action should be struck out Statutory Interpretation – Statutes – Repealing – Repeal of Rules of Court O 3 r 5 – Effect of repeal – Distinction between substantive and procedural rights – Whether amendments to procedural rules affect rights of parties retrospectively – Whether rights under repealed order survive – s 16(1)(c) Interpretation Act (Cap 1, 1999 Ed) Words and Phrases – 'Contumelious conduct' (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction This appeal arose from an application by Mr Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam, the appellant (`the appellant`), to strike out the action in Suit 224/97 initiated by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the respondent (`the respondent`). The application was heard before the senior assistant registrar and was dismissed. The appellant appealed to a judge-in-chambers, and the appeal was heard before Lai Siu Chiu J. The judge dismissed it and against her decision the appellant now brings this appeal. -

Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia

TRANSPARENCY AND AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The 1997–98 Asian economic crisis raised serious questions for the remaining authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia, not least the hitherto outstanding economic success stories of Singapore and Malaysia. Could leaders presiding over economies so heavily dependent on international capital investment ignore the new mantra among multilateral financial institutions about the virtues of ‘transparency’? Was it really a universal functional requirement for economic recovery and advancement? Wasn’t the free flow of ideas and information an anathema to authoritarian rule? In Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia Garry Rodan rejects the notion that the economic crisis was further evidence that ulti- mately capitalism can only develop within liberal social and political insti- tutions, and that new technology necessarily undermines authoritarian control. Instead, he argues that in Singapore and Malaysia external pres- sures for transparency reform were, and are, in many respects, being met without serious compromise to authoritarian rule or the sanctioning of media freedom. This book analyses the different content, sources and significance of varying pressures for transparency reform, ranging from corporate dis- closures to media liberalisation. It will be of equal interest to media analysts and readers keen to understand the implications of good governance debates and reforms for democratisation. For Asianists this book offers sharp insights into the process of change – political, social and economic – since the Asian crisis. Garry Rodan is Director of the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia. ROUTLEDGECURZON/CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Edited by Kevin Hewison and Vivienne Wee 1 LABOUR, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN INDUSTRIALIZING THAILAND Andrew Brown 2 ASIAN REGIONAL GOVERNANCE: CRISIS AND CHANGE Edited by Kanishka Jayasuriya 3 REORGANISING POWER IN INDONESIA The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets Richard Robison and Vedi R. -

Competing Narratives and Discourses of the Rule of Law in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2012] 298–330 SHALL THE TWAIN NEVER MEET? COMPETING NARRATIVES AND DISCOURSES OF THE RULE OF LAW IN SINGAPORE Jack Tsen-Ta Lee∗ This article aims to assess the role played by the rule of law in discourse by critics of the Singapore Government’s policies and in the Government’s responses to such criticisms. It argues that in the past the two narratives clashed over conceptions of the rule of law, but there is now evidence of convergence of thinking as regards the need to protect human rights, though not necessarily as to how the balance between rights and other public interests should be struck. The article also examines why the rule of law must be regarded as a constitutional doctrine in Singapore, the legal implications of this fact, and how useful the doctrine is in fostering greater solicitude for human rights. Singapore is lauded for having a legal system that is, on the whole, regarded as one of the best in the world,1 and yet the Government is often vilified for breaching human rights and the rule of law. This is not a paradox—the nation ranks highly in surveys examining the effectiveness of its legal system in the context of economic compet- itiveness, but tends to score less well when it comes to protection of fundamental ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, School of Law, Singapore Management University. I wish to thank Sui Yi Siong for his able research assistance. 1 See e.g., Lydia Lim, “S’pore Submits Human Rights Report to UN” The Straits Times (26 February 2011): On economic, social and cultural rights, the report [by the Government for Singapore’s Universal Periodic Review] lays out Singapore’s approach and achievements, and cites glowing reviews by leading global bodies. -

A Study of Chinese Blogosphere in Singapore

JeDEM 7(1): 23-45, 2015 ISSN 2075-9517 http://www.jedem.org Individualized and Depoliticized: A Study of Chinese Blogosphere in Singapore Carol Soon*, Jui Liang Sim** *Institute of Policy Studies, National University of Singapore, 1C Cluny Road House 5 Singapore 259599, [email protected], +65 6516 8372, **Institute of Policy Studies, National University of Singapore, 1C Cluny Road House 5 Singapore 259599, [email protected], +65 6516 5603 Abstract: Research on new media such as blogs examines users’ motivations and gratifications, and how individuals and organizations use them for political participation. In Singapore, political blogs have attracted much public scrutiny due to the bloggers’ online and offline challenges of official discourse. While previous research has established the political significance of these blogs, extant scholarship is limited to blogs written in the English language. Little is known about blogs maintained by the Chinese community, the largest ethnic group in multiracial Singapore. This study is a first to examine this community and the space they inhabit online. Through web crawling, we identified 201 Chinese-language blogs and through content analysis, we analysed if Chinese bloggers contributed to public debates and used their blogs for civic engagement. Their content, motivations for blogging in the language, hyperlinking practices and use of badges indicated that Chinese bloggers in Singapore do not use blogs for political participation and mobilization, but are individualized and a-politicized. We discuss possible reasons and implications in this paper. Keywords: new media, blogs, Chinese, Singapore, civic engagement Acknowledgement: This study is part of a research project by the Institute of Policy Studies on blogs written in three different vernacular languages (Chinese, Bahasa Malayu and Tamil). -

1 Response by Mr Lim Hng Kiang, Minister for Trade

RESPONSE BY MR LIM HNG KIANG, MINISTER FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY DURING THE COMMITTEE OF SUPPLY DEBATE Let me take Mr Steve Chia’s question. I think, first, he must understand how to interpret statistics. When the statistics shows that the income has risen, it does not mean that there could not be 3 per cent people who are unemployed and therefore, the income has dropped. This is the per capita GNI, gross national income, which looks at the average numbers. 2 PM, in his speech on 19 Jan 2005, mentioned that the overall per capita income had increased since 1998 and I think, indeed, it had increased because the per capita income is a widely-used benchmark in international comparison. So, we are using internationally accepted statistics and the method of measuring statistics. The per capita income is obtained by dividing the gross national income (GNI) by the population and therefore, the gross national income which is the income receivable by all residents of the economy would include both Singaporeans and foreigners. 3 Mr Steve Chia claimed that this would distort the numbers because it would include the high-earning expatriates. I think he would realize that the number of expatriates and people with employment pass were in fact a smaller percentage compared with the larger pool of other types of foreign workers. So if anything, the foreigner element of the calculation in Singapore’s context would tend to drag the number down. Even if we excluded foreigners, the latest statistics showed that the average income of Singaporeans in 2004 is 10.1 per cent higher than in 1998; compared to 10 years ago, the average income of Singaporeans had increased by 25.1 per cent. -

Official Publication of the Law Society of Singapore | August 2016

Official Publication of The Law Society of Singapore | August 2016 Thio Shen Yi, Senior Counsel President The Law Society of Singapore A RoadMAP for Your Journey The 2016 Mass Call to the Bar will be held this month on 26 Modern psychology tells us employees are not motivated and 27 August over three sessions in the Supreme Court. by their compensation – that’s just a hygiene factor. Pay Over 520 practice trainees will be admitted to the roll of mustn’t be an issue in that it must be fair, and if there is a Advocates & Solicitors. differential with their peers, then ceteris paribus, it cannot be too significant. Along with the Chief Justice, the President of the Law Society has the opportunity to address the new cohort. I Instead, enduring motivation is thought to be driven by three had the privilege of being able to do so last year in 2015, elements, mastery, autonomy, and purpose. There’s some and will enjoy that same privilege this year. truth in this, even more so in the practice of law, where we are first and foremost, members of an honourable The occasion of speaking to new young lawyers always profession. gives me pause for thought. What can I say that will genuinely add value to their professional lives? Making Mastery: The challenge and opportunity to acquire true motherhood statements is as easy as it is pointless. They expertise. There is a real satisfaction in being, and becoming, are soon forgotten, even ignored, assuming that they are really good at something. Leading a cross-border deal heard in the first place. -

2020-Sghc-255-Pdf.Pdf

IN THE COURT OF THREE JUDGES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2020] SGHC 255 Court of Three Judges/Originating Summons No 2 of 2020 In the matter of Sections 94(1) and 98(1) of the Legal Profession Act (Cap 161, 2009 Rev Ed) And In the matter of Lee Suet Fern (Lim Suet Fern), an Advocate and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Singapore Between Law Society of Singapore … Applicant And Lee Suet Fern (Lim Suet Fern) … Respondent JUDGMENT [Legal Profession] [Solicitor-client relationship] [Legal Profession] [Professional conduct] — [Breach] This judgment is subject to final editorial corrections approved by the court and/or redaction pursuant to the publisher’s duty in compliance with the law, for publication in LawNet and/or the Singapore Law Reports. Law Society of Singapore v Lee Suet Fern (alias Lim Suet Fern) [2020] SGHC 255 Court of Three Judges — Originating Summons No 2 of 2020 Sundaresh Menon CJ, Judith Prakash JA and Woo Bih Li J 13 August 2020 20 November 2020 Judgment reserved. Sundaresh Menon CJ (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 This is an application by the Law Society of Singapore (“the Law Society”) for an order pursuant to s 98(1)(a) of the Legal Profession Act (Cap 161, 2009 Rev Ed) (“the LPA”) that the respondent, Mrs Lee Suet Fern (alias Lim Suet Fern) (“the Respondent”), be subject to the sanctions provided for under s 83(1) of that Act. At the time of the proceedings before the disciplinary tribunal (“the DT”), the Respondent was an advocate and solicitor of the Supreme Court of Singapore of 37 years’ standing and practised as a director of Morgan Lewis Stamford LLC, a law corporation.