Gitanjali and Beyond Issue 3 Typeset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2011 Issue 36

Express Summer 2011 Issue 36 Portrait of a Survivor by Thomas Ország-Land John Sinclair by Dave Russell Four Poems from Debjani Chatterjee MBE Per Ardua Ad Astra by Angela Morkos Featured Artist Lorraine Nicholson, Broadsheet and Reviews Our lastest launch: www.survivorspoetry.org ©Lorraine Nicolson promoting poetry, prose, plays, art and music by survivors of mental distress www.survivorspoetry.org Announcing our latest launch Survivors’ Poetry website is viewable now! Our new Survivors’ Poetry {SP} webite boasts many new features for survivor poets to enjoy such as; the new videos featuring regular performers at our London events, mentees, old and new talent; Poem of the Month, have your say feedback comments for every feature; an incorporated bookshop: www.survivorspoetry.org/ bookshop; easy sign up for Poetry Express and much more! We want you to tell us what you think? We hope that you will enjoy our new vibrant place for survivor poets and that you enjoy what you experience. www.survivorspoetry.org has been developed with the kind support of all the staff, board of trustess and volunteers. We are particularly grateful to Judith Graham, SP trustee for managing the project, Dave Russell for his development input and Jonathan C. Jones of www.luminial.net whom built the website using Wordpress, and has worked tirelessly to deliver a unique bespoke project, thank you. Poetry Express Survivors’ Poetry is a unique national charity which promotes the writing of survivors of mental 2 – Dave Russell distress. Please visit www.survivorspoetry. com for more information or write to us. A Survivor may be a person with a current or 3 – Simon Jenner past experience of psychiatric hospitals, ECT, tranquillisers or other medication, a user of counselling services, a survivor of sexual abuse, 4 – Roy Birch child abuse and any other person who has empathy with the experiences of survivors. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Never Look Away

NEVER LOOK AWAY An original screenplay by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck 1. INT. DRESDEN ART MUSEUM – DAY KURT, a small 5-year-old boy with steel grey eyes gazes at the distorted, grimacing faces of soldiers from the hands of Otto Dix, the twisted colors and shapes of Kirchner, Heckel and Schmidt-Rottluff, the bizarre world of Paul Klee. At Kurt's side is his AUNT ELISABETH, an 19 year-old blonde of seductive beauty. They are part of a group of maybe two dozen adults, all ears to a self- confidently eloquent EXHIBITION GUIDE: GUIDE (nodding with regret) Modern art. Yes, ladies and gentlemen. Before the National Socialists took charge, Germany, too, had its share of "modern" art, meaning: something different just about every year - as follows from the word itself. Ironic chuckles from the audience. EXHIBITION GUIDE (CONT'D) But the Germany of National Socialism once again demands a German art which, like the entirety of a nation’s creative values, must be, and shall be, eternal. Bearing no such eternal value for its nation, it can be of no higher value even today. As they stroll past paintings of unconstrained prostitutes, yellow hydrocephalic heads, smirking captains of industry, African-style sculptures… EXHIBITION GUIDE (CONT'D) The German woman is ridiculed and equaled to prostitutes. The paintings appear to confirm this. EXHIBITION GUIDE (CONT'D) The soldier is portrayed either as a murderer or as the victim of senseless slaughter, all this in an attempt to destroy the German people’s deeply rooted respect for a soldier’s bravery. -

Anna Magnani

5 JUL 19 5 SEP 19 1 | 5 JUL 19 - 5 SEP 19 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT HOME OF THE EDINBURGH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Filmhouse, Summer 2019, Part II Luckily I referred to the last issue of this publication as the early summer double issue, which gives me the opportunity to call this one THE summer double issue, as once again we’ve been able to cram TWO MONTHS (July and August) of brilliant cinema into its pages. Honestly – and honesty about the films we show is one of the very cornerstones of what we do here at Filmhouse – should it become a decent summer weather-wise, please don’t let it put you off coming to the cinema, for that would be something of an, albeit minor in the grand scheme of things, travesty. Mind you, a quick look at the long-term forecast tells me you’re more likely to be in here hiding from the rain. Honestly…? No, I made that last bit up. I was at a world-renowned film festival on the south coast of France a few weeks back (where the weather was terrible!) seeing a great number of the films that will figure in our upcoming programmes. A good year at that festival invariably augurs well for a good year at this establishment and it’s safe to say 2019 was a very good year. Going some way to proving that statement right off the bat, one of my absolute favourites comes our way on 23 August, Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory which is simply 113 minutes of cinematic pleasure; and, for you, dear reader, I put myself through the utter bun-fight that was getting to see Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time.. -

Debjani Chatterjee

Monkey King's Party Debjani Chatterjee Illustrated by Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley This ebook belongs to: Published by Poggle Press, an imprint of Indigo Timmins Ltd • Pure Offices • Leamington Spa • Warwickshire CV34 6WE ISBN: 978-0-9573501-2-0 Text © Debjani Chatterjee 2013 Illustration © Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley 2013 All rights reserved. Debjani Chatterjee and Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley have asserted their moral right to be identified as the author and artists respectively of the work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is sold subject to the condition that it will not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without any similar condition, including this condition, being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser. www.springboardstories.co.uk Monkey King's Party Debjani Chatterjee An adaptation of a story from The Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en Illustrated by Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley A Poggle Press publication For Rishi – Munnu Dida Monkey King lived on the beautiful Fruit ‘n’ Flower Mountain. All the monkeys loved him because he was funny, friendly and brave. However, he was also very cheeky. Monkey King loved his mountain. He loved its flowers and he loved its fruits. But most of all, he loved to party. One day a traveller called Lao Tzu passed by. Monkey King saw that he was tired and hungry, so offered him some fruits. -

Never Look Away German Artist Gerhard Richter (B. 1932) May Not

Never Look Away German artist Gerhard Richter (b. 1932) may not be a household name in the US, but he is renowned in the art world and has been called “the greatest living artist,” conducting, over a 65-year period, an amazingly protean career in every aspect of the visual arts. The beginnings of that career are the inspiration for a new movie, “Never Look Away,” made by director Florian von Donnersmarck. The filmmaker achieved renown with first film “The Lives of Others” (2006) which earned him, at age 33, an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, a category for which he is nominated again this year. An open question for moviegoers approaching von Donnersmark’s film (which he also wrote) is how much does one need to know about the real Richter to appreciate and assess the fictionalized version? The story, a complex one, begins in 1937 with a young Kurt Barnert (standing in for Richter) observing, with a beloved aunt, Elisabeth (Saskia Rosendahl), an exhibition of “degenerate art” mounted by the Nazis in Dresden. However. Elisabeth, a smart and sensitive sort, admires the modernistic works, passing along her taste to her nephew. Later, she is sterilized and killed by the Nazis because she is deemed schizophrenic. Her sterilization is carried out by Professor Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch), an obstetrician and member of the SS. Switch to post-war Dresden where the young Kurt (Tom Schilling) begins to study painting at the city’s art school and meets and falls for Ellie Seeband (Paula Beer), daughter of the infamous doctor (unknown to Kurt) who has survived the war and become a dutiful, and successful, communist in East Germany. -

Annual Report 2014-15 ICSSR Annual Report 2014-15 ICSSR

Annual Report 2014-15 ICSSR Annual Report 2014-15 ICSSR Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, JNU Institutional Area, New Delhi - 110067 Tel No. 26741849/50/51 Fax : 91-11-26741836 Ministry of Human Resource Development e-mail : [email protected] Website : www.icssr.org Government of India Annual Report 2014-15 Indian Council Of Social Science Research Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, J.N.U. Institutional Area, New Delhi-110067 Contents Programmes 1-48 1. Overview 1-3 2. Research Promotion 4-12 3. Documentation 13-16 4. Research Survey and Publications 17-18 5. International Collaboration 19-31 6. Regional Centers 32-37 7. Research Institutes 38-47 Appendices 49-480 1. List of Members of the Council 51-53 2. ICSSR Senior Officials 54-55 3. Research Projects 56-107 4. Research Fellowships 108-193 5. Financial Assistance Provided for Organising 194-200 Capacity Building Programmes and Research Methodology Courses. 6. Financial Assistance Provided for Organising 201-244 International / National Seminars/ Conferences/ Workshops in India. 7. Publication Grants 245-250 8. Financial Assistance Provided to Scholars for 251-268 Participation in International Conferences / Data Collection Abroad. 9. Major Activities of ICSSR Regional Centres 269-296 10. Major Activities of ICSSR Research Institutes 297-475 11. Theses Purchased / Bibliographies Prepared in 476-479 the NASSDOC Statement of Accounts 481-580 Programmes 1 Overview Social science research, which presupposes launched in May 1969. It was considered a freedom of intellectual choice and opinion, significant achievement of evolving Indian needs to be encouraged by a developing democracy. nation. India has not only encouraged it, but also promoted it with state patronage. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Academy Invites 842 to Membership

MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] July 1, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ACADEMY INVITES 842 TO MEMBERSHIP LOS ANGELES, CA – The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is extending invitations to join the organization to 842 artists and executives who have distinguished themselves by their contributions to theatrical motion pictures. The 2019 class is 50% women, 29% people of color, and represents 59 countries. Those who accept the invitations will be the only additions to the Academy’s membership in 2019. Six individuals (noted by an asterisk) have been invited to join the Academy by multiple branches. These individuals must select one branch upon accepting membership. New members will be welcomed into the Academy at invitation-only receptions in the fall. The 2019 invitees are: Actors Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje – “Suicide Squad,” “Trumbo” Yareli Arizmendi – “A Day without a Mexican,” “Like Water for Chocolate” Claes Bang – “The Girl in the Spider’s Web,” “The Square” Jamie Bell – “Rocketman,” “Billy Elliot” Bob Bergen – “The Secret Life of Pets,” “WALL-E” Bruno Bichir – “Crónica de un Desayuno,” “Principio y Fin” Claire Bloom – “The King’s Speech,” “Limelight” Héctor Bonilla – “7:19 La Hora del Temblor,” “Rojo Amanecer” Juan Diego Botto – “Ismael,” “Vete de Mí” Sterling K. Brown – “Black Panther,” “Marshall” Gemma Chan – “Crazy Rich Asians,” “Mary Queen of Scots” Rosalind Chao – “I Am Sam,” “The Joy Luck Club” Camille Cottin – “Larguées,” “Allied” Kenneth Cranham – “Maleficent,” “Layer Cake” Marina de Tavira – “Roma,” “La Zona (The -

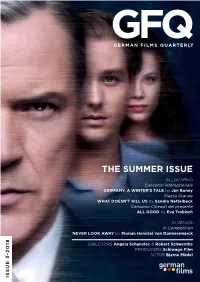

The Summer Issue

GFQ3_18_Druckvorlage.qxp_Layout 1 25.07.18 14:47 Seite 1 GFQ GERMAN FILMS QUARTERLY THE SUMMER ISSUE IN LOCARNO Concorso internazionale GERMANY. A WINTER’S TALE by Jan Bonny Piazza Grande WHAT DOESN’T KILL US by Sandra Nettelbeck Concorso Cineasti del presente ALL GOOD by Eva Trobisch IN VENICE In Competition NEVER LOOK AWAY by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck DIRECTORS Angela Schanelec & Robert Schwentke PRODUCERS Schiwago Film ACTOR Bjarne Mädel ISSUE 3-2018 GFQ3_18_Druckvorlage.qxp_Layout 1 25.07.18 14:47 Seite 2 CONTENTS GFQ 3-2018 18 20 23 24 26 28 29 30 32 35 36 36 2 GFQ3_18_Druckvorlage.qxp_Layout 1 25.07.18 14:47 Seite 3 GFQ 3-2018 CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE PORTRAITS NEW DOCUMENTARIES LIFE IN THE TIME OF NO BELONGING DEFENDER OF THE FAITH A portrait of director Angela Schanelec .......................................... 4 Christoph Röhl ................................................................................. 34 AT HOME IN TWO WORLDS DIE GEHEIMNISSE DES SCHÖNEN LEO A portrait of director Robert Schwentke ......................................... 6 THE SECRETS OF HANDSOME LEO Benedikt Schwarzer .............. 34 HANDS ON PRODUCERS STILLER KAMERAD A portrait of Schiwago Film .............................................................. 8 SILENT COMRADE Leonhard Hollmann .......................................... 35 IN SEARCH OF NEW CHALLENGES SUNSET OVER MULHOLLAND DRIVE A portrait of actor Bjarne Mädel ....................................................... 10 Uli Gaulke ......................................................................................... -

Film Calendar February 8 - April 4, 2019

FILM CALENDAR FEBRUARY 8 - APRIL 4, 2019 TRANSIT A Christian Petzold Film Opens March 15 Chicago’s Year-Round Film Festival 3733 N. Southport Avenue, Chicago www.musicboxtheatre.com 773.871.6607 CATVIDEOFEST RUBEN BRANDT, THE FILMS OF CHRISTIAN PETZOLD IDA LUPINO’S FEBRUARY COLLECTOR HARMONY KORINE MATINEE SERIES THE HITCH-HIKER 16, 17 & 19 OPENS MARCH 1 MARCH 15-21 WEEKENDS AT 11:30AM MARCH 4 AT 7PM Welcome TO THE MUSIC BOX THEATRE! FEATURE FILMS 4 COLD WAR NOW PLAYING 4 OSCAR-NOMINATED DOC SHORTS OPENS FEBRUARY 8 6 AMONG WOLVES FEBRUARY 8-14 6 NEVER LOOK AWAY OPENS FEBRUARY 15 8 AUDITION FEBRUARY 15 & 16 9 LORDS OF CHAOS OPENS FEBRUARY 22 9 RUBEN BRANDT, COLLECTOR OPENS MARCH 1 11 BIRDS OF PASSAGE OPENS MARCH 8 FILM SCHOOL DEDICATED 12 TRANSIT OPENS MARCH 15 The World’s Only 17 WOMAN AT WAR OPENS MARCH 22 TO COMEDY 18 COMMENTARY SERIES Comedy Theory. Storytelling. Filmmaking. Industry Leader Masterclasses. 24 CLASSIC MATINEES Come make history with us. RamisFilmSchool.com 26 CHICAGO FILM SOCIETY 28 SILENT CINEMA 30 MIDNIGHTS SPECIAL EVENTS 7 VALENTINE’S DAY: CASABLANCA FEBRUARY 10 VALENTINE’S DAY: THE PRINCESS BRIDE FEBRUARY 13 & 14 8 CAT VIDEO FEST FEBRUARY 16, 17 & 19 10 JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL MARCH 1-17 10 THE HITCH-HIKER MARCH 4 11 PARTS OF SPEECH: HARI KUNZRU MARCH 12 14 HARMONY KORINE FILM SERIES MARCH 15-21 17 DECONSTRUCTING THE BEATLES MARCH 30 & APRIL 3 Brian Andreotti, Director of Programming VOLUME 37 ISSUE 154 Ryan Oestreich, General Manager Copyright 2019 Southport Music Box Corp. -

English Books

NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English Books 020 LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCES 1. Arora, Jagdish, ed. Library as a global information hub : perspectives and challenges : proceedings, December 7-8, 2007 at Gauhati University, Guwahati / edited by Jagdish Arora... [et al]. - Ahmedabad: INFLIBNET Centre , 2007. v, 458p.: tables: figs.: illus.; 24cm. Includes bibliographical references; jointly organised by Information and Library Network Centre, Ahmedabad and Department of Library and Information Science; 5th Convention PLANNER-2007. ISBN : 978-81-902079-5-9. 025.5 LIB C76580 2. Nordic public libraries 2.0. - Kobenhavn V: Danish Agency for Libraries and Media , 2010. 112p.: plates; 28cm. ISBN : 978-87-92681-02-7. 027.448 NOR C76551 080 GENERAL COLLECTIONS 3. Mukherji, Pranab Selected speeches / Pranab Mukherjee. - New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting , 2015. 3v.: plates; 25cm. Contents: v.1-v.3 July 2012-July 2015. ISBN : 978-81-230-2019-8. 080 MUK-s B212105;v.1,B212106;v.2, B212107;v.3,C77058;v.1;1, C77059;v.2;1,C77060;v.3;1 4. Kundu, Kalyan Meeting with Mussolini: Tagore's tours in Italy : 1925 and 1926 / Kalyan Kundu. - New Delhi: Oxford University Press , 2015. xxx, 250p.: plates; 23cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN : 0-19-945908-8. 080 TAG-k C76539 Price : RS. ***750.00 2 5. Som, Reba, ed. Tagore and Russia : international seminar of ICCR held on September 28-29, 2011 at Russian State University for Humanities, Moscow / edited by Reba Som and Sergei Serebriany. - New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications , 2016. 190p.; 26cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN : 978-81-241-1914-3.