Chinese Mine Warfare: a PLA Navy 'Assassin's Mace' Capability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program

Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 14, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41129 Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program Summary The Navy’s Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program is a program to design and build a class of 12 new SSBNs to replace the Navy’s current force of 14 aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Since 2013, the Navy has consistently identified the Columbia-class program as the Navy’s top priority program. The Navy procured the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021 and wants to procure the second boat in the class in FY2024. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $3,003.0 (i.e., $3.0 billion) in procurement funding for the first Columbia-class boat and $1,644.0 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in advance procurement (AP) funding for the second boat, for a combined FY2022 procurement and AP funding request of $4,647.0 million (i.e., about $4.6 billion). The Navy’s FY2022 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of the first Columbia- class boat at $15,030.5 million (i.e., about $15.0 billion) in then-year dollars, including $6,557.6 million (i.e., about $6.60 billion) in costs for plans, meaning (essentially) the detail design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the Columbia class. (It is a long-standing Navy budgetary practice to incorporate the DD/NRE costs for a new class of ship into the total procurement cost of the first ship in the class.) Excluding costs for plans, the estimated hands-on construction cost of the first ship is $8,473.0 million (i.e., about $8.5 billion). -

A Chinese Experiment in Allocating Land Conversion Rights

WP 2015-13 November 2015 Working Paper The Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7801 USA Networked Leaders in the Shadow of the Market – A Chinese Experiment in Allocating Land Conversion Rights Nancy H. Chau† Yu Qin‡ Weiwen Zhang§ It is the policy of Cornell University actively to support equality of educational and employment opportunity. No person shall be denied admission to any educational program or activity or be denied employment on the basis of any legally prohibited discrimination involving, but not limited to, such factors as race, color, creed, religion, national or ethnic origin, sex, age or handicap. The University is committed to the maintenance of affirmative action programs which will assure the continuation of such equality of opportunity. Networked Leaders in the Shadow of the Market { A Chinese Experiment in Allocating Land Conversion Rights Nancy H. Chauy Yu Qinz Weiwen Zhangx This version: July 2015 Abstract: Concerns over the loss of cultivated land in China have motivated a system of centrally mandated annual land use quotas effective from provincial down to township levels. To facilitate ef- ficient land allocation, a ground-breaking policy in the Zhejiang Province permitted sub-provincial units to trade land conversion quotas. We theoretically model and empirically estimate the drivers of local government participation in this program to shed light more broadly on the drivers of local government decision-making. We find robust support for three sets of factors at the sub-provincial level: market forces, administrative autonomy, and prior network connections of local government leaders. -

How China's Leaders Think: the Inside Story of China's Past, Current

bindex.indd 540 3/14/11 3:26:49 PM China’s development, at least in part, is driven by patriotism and pride. The Chinese people have made great contributions to world civilization. Our commitment and determination is rooted in our historic and national pride. It’s fair to say that we have achieved some successes, [nevertheless] we should have a cautious appraisal of our accomplishments. We should never overestimate our accomplish- ments or indulge ourselves in our achievements. We need to assess ourselves objectively. [and aspire to] our next higher goal. [which is] a persistent and unremitting process. Xi Jinping Politburo Standing Committee member In the face of complex and ever-changing international and domes- tic environments, the Chinese Government promptly and decisively adjusted our macroeconomic policies and launched a comprehensive stimulus package to ensure stable and rapid economic growth. We increased government spending and public investments and imple- mented structural tax reductions. Balancing short-term and long- term strategic perspectives, we are promoting industrial restructuring and technological innovation, and using principles of reform to solve problems of development. Li Keqiang Politburo Standing Committee member I am now serving my second term in the Politburo. President Hu Jintao’s character is modest and low profile. we all have the high- est respect and admiration for him—for his leadership, perspicacity and moral convictions. Under his leadership, complex problems can all get resolved. It takes vision to avoid major conflicts in soci- ety. Income disparities, unemployment, bureaucracy and corruption could cause instability. This is the Party’s most severe test. -

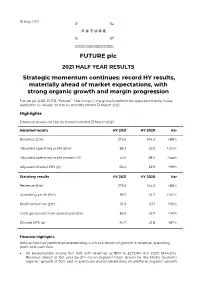

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress (name redacted) Specialist in Naval Affairs December 13, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RS22478 Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Summary Names for Navy ships traditionally have been chosen and announced by the Secretary of the Navy, under the direction of the President and in accordance with rules prescribed by Congress. Rules for giving certain types of names to certain types of Navy ships have evolved over time. There have been exceptions to the Navy’s ship-naming rules, particularly for the purpose of naming a ship for a person when the rule for that type of ship would have called for it to be named for something else. Some observers have perceived a breakdown in, or corruption of, the rules for naming Navy ships. On July 13, 2012, the Navy submitted to Congress a 73-page report on the Navy’s policies and practices for naming ships. For ship types now being procured for the Navy, or recently procured for the Navy, naming rules can be summarized as follows: The first Ohio replacement ballistic missile submarine (SBNX) has been named Columbia in honor of the District of Columbia, but the Navy has not stated what the naming rule for these ships will be. Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarines are being named for states. Aircraft carriers are generally named for past U.S. Presidents. Of the past 14, 10 were named for past U.S. Presidents, and 2 for Members of Congress. Destroyers are being named for deceased members of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, including Secretaries of the Navy. -

Appendix A. Navy Activity Descriptions

Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 APPENDIX A Navy Activity Descriptions Appendix A Navy Activity Descriptions Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 This page intentionally left blank. Appendix A Navy Activity Descriptions Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Draft EIS/OEIS June 2017 Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing TABLE OF CONTENTS A. NAVY ACTIVITY DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................................ A-1 A.1 Description of Sonar, Munitions, Targets, and Other Systems Employed in Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Events .................................................................. A-1 A.1.1 Sonar Systems and Other Acoustic Sources ......................................................... A-1 A.1.2 Munitions .............................................................................................................. A-7 A.1.3 Targets ................................................................................................................ A-11 A.1.4 Defensive Countermeasures ............................................................................... A-13 A.1.5 Mine Warfare Systems ........................................................................................ A-13 A.1.6 Military Expended Materials ............................................................................... A-16 A.2 Training Activities .................................................................................................. -

Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 1 of 13

Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 1 of 13 Submarines in the United States Navy There are three major types of submarines in the United States Navy: ballistic missile submarines, attack submarines, and cruise missile submarines. All submarines in the U.S. Navy are nuclear-powered. Ballistic subs have a single strategic mission of carrying nuclear submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Attack submarines have several tactical missions, including sinking ships and subs, launching cruise missiles, and gathering intelligence. The submarine has a long history in the United States, beginning with the Turtle, the world's first submersible with a documented record of use in combat.[1] Contents Early History (1775–1914) World War I and the inter-war years (1914–1941) World War II (1941–1945) Offensive against Japanese merchant shipping and Japanese war ships Lifeguard League Cold War (1945–1991) Towards the "Nuclear Navy" Strategic deterrence Post–Cold War (1991–present) Composition of the current force Fast attack submarines Ballistic and guided missile submarines Personnel Training Pressure training Escape training Traditions Insignia Submarines Insignia Other insignia Unofficial insignia Submarine verse of the Navy Hymn See also External links References https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Submarines_in_the_United_States_Navy 3/24/2018 Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 2 of 13 Early History (1775–1914) There were various submersible projects in the 1800s. Alligator was a US Navy submarine that was never commissioned. She was being towed to South Carolina to be used in taking Charleston, but she was lost due to bad weather 2 April 1863 off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. -

Back Issues Available

INRO Available Back Issues of Warship International August 2015 VOL. 3, No. 1 1966 Featuring: Losses – Royal Italian Navy 1915-18; Lexington Battle Cruisers; The Early Jean Barts; Soviet Potpourri.. Vol. 20, No. 3 1983 Featuring: The Development of “A” Class Cruisers in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Part VI. Vol. 21, No. 1 1984 Featuring: NRC/INRO the First 20 Years; An INRO Library; Early Spanish Steam Warships, Part II; Exterior Ballistics with Microcomputers. Vol. 21, No. 2 1984 Featuring: Sparrows Among the Hawks; Elisabeta; Elisabeta and Her Armament; New Developments in the Soviet Navy; The Spanish Navy of 1898; Battleships, A Vulnerable Anachronism? Vol. 21, No. 3 1984 Featuring: The Development of the “A Class” Cruisers in the Japanese Navy, Part VII. Vol. 23, No. 3 1986 Featuring: The Thai Navy; The U.S. Fleet at the New York World’s Fair, 1939; The Last, Strange Cruise of UB-88. Vol. 24, No. 1 1987 Featuring: Phantom Fleet – The Confederacy’s Unclaimed European Warships; Sous La Crois De Lorraine (Under the Cross of Lorraine); Japanese Naval Construction, 1915-45; HMNZS Tui; The Mystery of the Austro-Hungarian submarine U-30. Vol. 24, No. 2 1987 Featuring: The Loss of HMS Hood – A Re-examination; Developments in the Soviet Navy; The fate of the Chinese Torpedo Gunboat Fei Ting; The Fate of the Four Chinese Torpedo Boat Destroyers. Vol. 24, No. 3 1987 Featuring: U.S. Navy in WW II – A Basic Bibliography; A Day at the New York Navy Yard; 50 Years of Army Dredge Boats; The Attack on the USS Stark; Battleships – Impressions of a Dinosaur; Submarine Hull design and Diving Depths Between the Wars. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

As of April 7, 2014 Select List of Delegates Boao Forum for Asia

As of April 7, 2014 Select List of Delegates Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2014 State/Government Leaders 1. H.E. LI Keqiang, Premier, State Council, the People’s Republic of China 2. The Hon. Tony Abbott, Prime Minister, the Common-wealth of Australia 3. H.E. Chung Hongwon, Prime Minister, Republic of Korea 4. H.E. Thongsing Thammavong, Prime Minister, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic 5. Rt. Hon. Dr. Hage Geingob, Prime Minister, the Republic of Namibia 6. H.E. Nawaz Sharif, Prime Minister, Islamic Republic of Pakistan 7. H.E. Kay Rala Xanana Gusmao, Prime Minister, the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste 8. H.E. Arkady Vladimirovich Dvorkovich, Deputy Prime Minister, Russian Federation 9. H.E. Vu Duc Dam, Vice Prime Minister, Socialist Republic of Vietnam 10. H. E. YANG Jiechi, State Councilor, People’s Republic of China 11. FUKUDA Yasuo, Former Prime Minister, Japan 12. ZENG Peiyan, Former Vice Premier, China 13. Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad BADAWI, Former Prime Minister, Malaysia 14. GOH Chok Tong, Emeritus Senior Minister, Republic of Singapore 15. Jean-Pierre RAFFARIN, Former Prime Minister, France 16. Dominique de VILLEPIN, former Prime Minister, France 17. Fidel V. RAMOS, Former President, the Philippines 18. Bob HAWKE, Former Prime Minister of Australia 19. HAN Duck-Soo, Chairman, KITA; Former Prime Minister, Republic of Korea 20. ZHOU Xiaochuan, Governor, People’s Bank of China 21. Surakiart SATHIRATHAI, Chairman of the Asian Peace and Reconciliation Council (APRC), Former Deputy Prime Minister & Minister of Foreign Affairs of Thailand 22. Peter COSTELLO, Former Treasurer, Commonwealth of Australia; Chairman, Australian Government Sovereign Wealth Fund, Future Fund; Managing Director, BKK Partners; Chairman, ECG Advisory Solutions 23. -

English Comes from the French: Guerre De Course

The Maritime Transport War - Emphasizing a strategy to interrupt the enemy sea lines of communication1 (SLOCs) - ARAKAWA Kenichi Preface Why did the Imperial Japanese Navy not aggressively develop a strategy to interrupt the enemy sea line of communication (SLOC) during the Second World War? Japan’s SLOC connecting her southern and Asian continental fronts to the mainland were destroyed mainly by the U.S. submarine warfare. Consequently, Japanese forces suffered from shortages of provisions as well as natural resources necessary for her military power. Furthermore, neither weapons nor provisions could be delivered to the fronts due to the U.S. operations to disrupt the Japanese SLOCs between the battlegrounds and the Japanese home island. Thus soldiers on the front were threatened with starvation even before the battle. In contrast, the U.S. and British military forces supported long logistical supply lines to their Asian and Pacific battlegrounds. However, there are no records indicating that the Imperial Japanese Navy attempted to interrupt these vital sea lines. Surely Japanese officers were aware of the German use of submarines in World WarⅠ. Why did the Imperial Japanese Navy not adopt a guerre de course strategy, that is a strategy targeting the enemy merchant marine and logistical lines? The most comprehensive explanation indicates that the Imperial Japanese Navy had no doctrine providing for this kind of warfare. The core of its naval strategy was the doctrine of “decisive battles at any cost.” Under the Japanese naval doctrine submarines were meant to contribute to fleet engagements not to have an independent combat role or to target anything but the enemy fleet. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships.