Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture's Ephemeral Practices

____________________ A PATAPHYSICAL READING OF THE MAISON DE VERRE ______183 A “PATAPHYSICAL” READING OF THE MAISON DE VERRE Mary Vaughan Johnson Virginia Tech The Maison de Verre (1928-32) is a glass-block the general…(It) is the science of imaginary house designed and built by Pierre Chareau solutions...”3 According to Roger Shattuck, in (1883-1950) in collaboration with the Dutch his introduction to Jarry’s Exploits & Opinions architect Bernard Bijvoët and craftsman Louis of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, “(i)f Dalbet for the Dalsace family at 31, rue St. mathematics is the dream of science, ubiquity Guillaume in Paris, France. A ‘pataphysical the dream of mortality, and poetry the dream reading of the Maison de Verre, undoubtedly of speech, ‘pataphysics fuses them into the one of the most powerful modern icons common sense of Dr. Faustroll, who lives all representing modernism’s alliance with dreams as one.” In the chapter dedicated to technology, is intended as an alternative C.V. Boys, Jarry, for instance, with empirical history that will yield new meanings of precision, describes Dr. Faustroll’s bed as modernity. Modernity in architecture is all too being 12 meters long, shaped like an often associated with the constitution of an elongated sieve that is in fact not a bed, but a epoch, a style developed around the turn of boat designed to float on water according to the 20th century in Europe albeit intimately tied Boys’ principles of physics.4 The image of a to its original meaning related to an attitude boat that is also a bed, at the same time, towards the passage of time.1 To be truly brings to mind the poem by Robert Louis modern is to be in the present. -

Franciszka Themerson Lines and Thoughts Paintings, Drawings, Calligrammes

! 44a Charlotte Road, London, EC2A 3PD Franciszka Themerson Lines and Thoughts paintings, drawings, calligrammes 4 November - 16 December 2016 ____________________ Private View: 3 November 6.30 - 8.30 pm Calligramme XXIII (‘fossil’),1961 (?), Black, gold and red paint on paper, 52 x 63.5cm, © Themerson Estate, courtesy of l’étrangère. " It seemed to me that the interrelation between these two sides: order in nature on the one side, and the human condition on the other, was the undefinable drama to be grasped, dealt with and communicated by me. - Franciszka Themerson, Bi-abstract Pictures, 1957 l’étrangère is delighted to present a solo exhibition of paintings, drawings and calligrammes by Franciszka Themerson - a seminal figure in the Polish pre-war avant-garde. She developed her unique pictorial language during the shifting years of pre- and post-war Europe, having settled in Britain in 1943. Together with her husband, writer, poet and filmmaker, Stefan Themerson, she was involved with experimental film and avant-garde publishing. Her personal domain, however, focused on painting, drawing, theatre sets and costume design. This exhibition brings together Franciszka’s three paintings completed in 1972 and a selection of drawings, dated from 1955 to 1986, which demonstrate the breadth of her work. ! The paintings: Piétons Apocalypse, A Person I Know and Coil Totem, act as anchors in the exhibition, while the drawings demonstrate the variety of motifs recurring throughout her work. The act of drawing and the key role of the line remain a constant throughout her practice. The images are characterised by a fluidity of line, rhythmic composition and the humorous depiction of everyday life. -

Ubu Roi Short FINAL

media contact: erica lewis-finein brightbutterfly[at]hotmail.com CUTTING BALL THEATER CONTINUES 15TH SEASON WITH “UBU ROI” January 24-February 23, 2014 In a new translation by Rob Melrose SAN FRANCISCO (December 16, 2013) – Cutting Ball Theater continues its 15th season with Alfred Jarry’s UBU ROI in a new translation by Rob Melrose. Russian director Yury Urnov (Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company) helms this irreverent take on world leaders. Featuring David Sinaiko, Ponder Goddard, Marilet Martinez, Bill Boynton, Nathaniel Justiniano, and Andrew Quick, UBU ROI plays January 24 through February 23 (Press opening: January 30) at the Cutting Ball Theater in residence at EXIT on Taylor (277 Taylor Street) in San Francisco. For tickets ($10-50) and more information, the public may visit cuttingball.com or call 415-525-1205. When Alfred Jarry’s UBU ROI premiered in Paris on December 10, 1896, the audience broke into a riot at the utterance of its first word. Jarry’s parody of Shakespeare’s Macbeth defies theatrical tradition through its disregard for audience expectations, replacing Shakespeare’s tragic hero with a greedy, sadistic ogre who becomes the King of Poland by force and through the debasement of his people. Set in a modern luxury kitchen, this re-visioned UBU ROI features a wealthy American couple who play out their fantasies of wealth and power to excess as they take on the roles of Mother and Father Ubu. Cutting Ball’s version of UBU ROI may bring to mind the fall from grace of many a contemporary political leader corrupted by power, from Elliot Spitzer to Dominique Strauss-Kahn. -

ABBAYE Livres

GEOFFROY J.-R. et BEQUET Y. S.VV Commissaires-Priseurs Habilités ROYAN, 6, Rue R. Poincaré, (17207 ) Tél: 05.46.38.69.35 -Fax: 05.46.39.28.05 E-mail : [email protected] SAINTES , 38 Bld Guillet-Maillet (Bureau annexe) Tél: 05.46.93.39.14 E-mail : [email protected] ,N° d’agrément 2002-204 VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES Jeudi 7 Décembre à 11h15 (Lots 1 à125) Jeudi 7 Décembre à 14h15 (Lots 125à fin) Abbaye aux Dames 17100 Saintes LIVRES et AUTOGRAPHES Expositions : Mercredi 6 Décembre de 14h à 19h et Jeudi 7 Décembre de 9h à 11h Expert Christine CHATON – 3, rue Gautier – 17100 Saintes Membre de la Chambre Nationale des Experts Spécialisés (C.N.E.S.) Tél : 06.08.92.27.75 / Fax : 09.81.70.96.13 / [email protected] : LISTE Vente du matin (11h15) 1 1. ALMANACHS & ÉTRENNES. XVIIIe - XIXe s. Réunion d’une trentaine de volumes 250 350 dont : - Le Meilleur Livre ou Les meilleures Etrennes que l’on puisse donner et recevoir. Paris, Prault, 1745. Cart. papier gaufré avec motifs doré. Etat moyen. - Calendrier de la Cour. (1764). In-32, reliure maroquin brun. - Les Spectacles de Paris ou Calendrier … des Théâtres (1770). - Étrennes Intéressantes (1780, An VI, An VIII, 1816), avec étuis. - Étrennes Nouvelles, commodes et utiles, imprimées par ordre de son Eminence Monseigneur le Cardinal de La Rochefoucauld… à l’usage de son diocèse. Rouen, Seyer, 1783. In-16, reliure veau brun (usagée). - Almanach des Muses (1783). In-12, broché. Pas de page de titre. - Calendrier du Limousin (Barbou, 1787). -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I am using the terms ‘space’ and ‘place’ in Michel de Certeau’s sense, in that ‘space is a practiced place’ (Certeau 1988: 117), and where, as Lefebvre puts it, ‘(Social) space is a (social) product’ (Lefebvre 1991: 26). Evelyn O’Malley has drawn my attention to the anthropocentric dangers of this theorisation, a problematic that I have not been able to deal with fully in this volume, although in Chapters 4 and 6 I begin to suggest a collaboration between human and non- human in the making of space. 2. I am extending the use of the term ‘ extra- daily’, which is more commonly associated with its use by theatre director Eugenio Barba to describe the per- former’s bodily behaviours, which are moved ‘away from daily techniques, creating a tension, a difference in potential, through which energy passes’ and ‘which appear to be based on the reality with which everyone is familiar, but which follow a logic which is not immediately recognisable’ (Barba and Savarese 1991: 18). 3. Architectural theorist Kenneth Frampton distinguishes between the ‘sceno- graphic’, which he considers ‘essentially representational’, and the ‘architec- tonic’ as the interpretation of the constructed form, in its relationship to place, referring ‘not only to the technical means of supporting the building, but also to the mythic reality of this structural achievement’ (Frampton 2007 [1987]: 375). He argues that postmodern architecture emphasises the scenographic over the architectonic and calls for new attention to the latter. However, in contemporary theatre production, this distinction does not always reflect the work of scenographers, so might prove reductive in this context. -

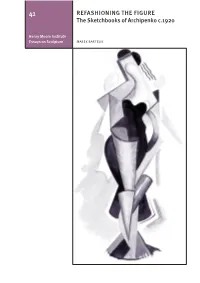

REFASHIONING the FIGURE the Sketchbooks of Archipenko C.1920

41 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.1920 Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture MAREK BARTELIK 2 3 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.19201 MAREK BARTELIK Anyone who cannot come to terms with his life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate…but with his other hand he can note down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different (and more) things than the others: after all, he is dead in his own lifetime, he is the real survivor.2 Franz Kafka, Diaries, entry on 19 October 1921 The quest for paradigms in modern art has taken many diverse paths, although historians have underplayed this variety in their search for continuity of experience. Since artists in their studios produce paradigms which are then superseded, the non-linear and heterogeneous development of their work comes to define both the timeless and the changing aspects of their art. At the same time, artists’ experience outside of their workplace significantly affects the way art is made and disseminated. The fate of artworks is bound to the condition of displacement, or, sometimes misplacement, as artists move from place to place, pledging allegiance to the old tradition of the wandering artist. What happened to the drawings and watercolours from the three sketchbooks by the Ukrainian-born artist Alexander Archipenko presented by the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is a poignant example of such a fate. Executed and presented in several exhibitions before the artist moved from Germany to the United States in the early 1920s, then purchased by a private collector in 1925, these works are now being shown to the public for the first time in this particular grouping. -

Mise En Page 1

BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. EDITIONSORIGINALES AUTOGRAPHESET MANUSCRITSDU XX E SIÈCLE MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 - SOTHEBY’S PARIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 Experts de la vente DOMINIQUE COURVOISIER Expert de la Bibliothèque nationale de France Membre du Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en œuvres d’art 5, rue de Miromesnil 75008 Paris Tél./Fax. + 33 (0)1 42 68 11 29 [email protected] ANNE HEILBRONN SOTHEBY’S 76, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré 75008 Paris Tél. +33 (0)1 53 05 53 18 Fax. +33 (0)1 53 05 52 23 [email protected] Tous nos remerciements à Monsieur Jean-Paul Goujon pour l’aide précieuse apportée à la rédaction des notices des manuscrits et des autographes MARDI 7 OCTOBRE 2014 À 14H30 VENTE À PARIS BIBLIOTHÈQUE R. ET B. L. ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES AUTOGRAPHES ET MANUSCRITS DU XXE SIÈCLE Vente dirigée par Cyrille Cohen et Alexandre Giquello Agréments du Conseil des Ventes Volontaires de Meubles aux Enchères Publiques n° 2001-002 et n° 2002-389 EXPOSITION Vendredi 3 et samedi 4 octobre de 10h à 18h Lundi 6 octobre de 10h à 20h sothebys.com/bidnow 76, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré - 75008 Paris tél. 33 (0)1 53 05 53 05 www.sothebys.com SPÉCIALISTES RESPONSABLES DE LA VENTE Pour toute information complémentaire concernant les lots de cette vente, veuillez contacter les experts listés ci-dessous. RÉFÉRENCE DE LA VENTE ENCHÈRES TÉLÉPHONIQUES PF1453 “Médaillon” & ORDRES D’ACHAT +33 (0)1 53 05 53 48 Fax +33 (0)1 53 05 52 93/94 EXPERTS DE LA VENTE [email protected] Dominique Courvoisier Les demandes d’enchères +33 (0)1 42 68 11 29 téléphoniques doivent nous [email protected] parvenir 24 heures avant la vente. -

By William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why Give

Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why give Welcome to our 2015 season with Measure for Measure. you me this Our Russian company were last here with The Tempest and we are delighted to be back. We are particularly grateful to shame? Evgeny Pisarev and Anna Volk of the Pushkin Theatre in Moscow, without whom this production would not have been possible. Act III Scene I Thanks also to Toni Racklin, Leanne Cosby, and the entire team at the Barbican, London for their continued enthusiasm and support, and to Katy Snelling and Louise Chantal at the Oxford Playhouse. We’d also like to thank our other co-producers, Les Gémeaux/ Sceaux/Scène Nationale, in Paris, and Centro Dramático Nacional, in Madrid, as well as Arts Council England. We do hope you enjoy the show… Declan Donnellan and Nick Ormerod Petr Rykov & Company 1 2 3 Cheek by Jowl in Russia In 1986, Russian theatre director Lev Dodin of Valery Shadrin, commissioned Donnellan invited Donnellan and Ormerod to visit his and Ormerod to form their own company of company in Leningrad. Ten years later, they Russian actors in Moscow. This sister company 4 5 6 directed and designed The Winter’s Tale performs in Russia and internationally and its for the Maly Drama Theatre, which is still current repertoire includes Boris Godunov running in St. Petersburg. Throughout the by Pushkin, Twelfth Night and The Tempest 1990s the Russian Theatre Confederation by Shakespeare, and Three Sisters by Anton regularly invited Cheek by Jowl to Moscow Chekhov. Measure for Measure is Cheek as part of the Chekhov International Theatre by Jowl’s first co-production with Moscow’s Festival, and this relationship intensified in Pushkin Theatre. -

Prints from the Age of Rodin Wall Labels

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Prints from the Age of Rodin - Ephemera Prints from the Age of Rodin Fall 2019 Prints from the Age of Rodin Wall Labels Fairfield University Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/rodin-prints-ephemera This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Angelo Jank (French, active 19th century) Woman with a Parrot from the portfolio L’Estampe Moderne, 1898 Color lithograph Gift of James Reed (2017.35.823) This lithograph was one of four that appeared in the volume of L’Estampe Moderne in the case below. Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867-1947) The Loge, 1898 Color lithograph Gift from the Dr. I. J. and Sarah Markens Art Collection (2018.34.26) Bonnard’s lithograph, which takes up the same subject of spectators at the opera as Lunois’ print above, appeared as the frontispiece to Mellerio’s book. Edward J. Steichen (American, 1879-1964) Portrait of Rodin with The Thinker and The Monument to Victor Hugo, 1902 Gelatin silver print Jundt Art Museum, Gonzaga University; Gift of Iris and B. -

Documentary Theatre, the Avant-Garde, and the Politics of Form

“THE DESTINY OF WORDS”: DOCUMENTARY THEATRE, THE AVANT-GARDE, AND THE POLITICS OF FORM TIMOTHY YOUKER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Timothy Earl Youker All rights reserved ABSTRACT “The Destiny of Words”: Documentary Theatre, the Avant-Garde, and the Politics of Form Timothy Youker This dissertation reads examples of early and contemporary documentary theatre in order to show that, while documentary theatre is often presumed to be an essentially realist practice, its history, methods, and conceptual underpinnings are closely tied to the historical and contemporary avant-garde theatre. The dissertation begins by examining the works of the Viennese satirist and performer Karl Kraus and the German stage director Erwin Piscator in the 1920s. The second half moves on to contemporary artists Handspring Puppet Company, Ping Chong, and Charles L. Mee. Ultimately, in illustrating the documentary theatre’s close relationship with avant-gardism, this dissertation supports a broadened perspective on what documentary theatre can be and do and reframes discussion of the practice’s political efficacy by focusing on how documentaries enact ideological critiques through form and seek to reeducate the senses of audiences through pedagogies of reception. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii INTRODUCTION: Documents, Documentaries, and the Avant-Garde 1 Prologue: Some History 2 Some Definitions: Document—Documentary—Avant-Garde -

La Gazette De L'hôtel Drouot

HÔTEL DROUOT – SALLE 4 MERCREDI 30 OCTOBRE 2019 À 14H INCUNABLES, LIVRES DU XVIe ILLUSTRÉS SCIENCES, MATHÉMATIQUES, ARCHITECTURE, RECUEILS DE GRAVURES DU XVIe AU XVIIIe ILLUSTRÉS DU XXe, ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES, ENVOIS AUTOGRAPHES SIGNÉS PHOTOGRAPHIES KAPANDJI MORHANGE A B N° 18 – Catalogue de vente du 30 octobre 2019 KAPANDJI MORHANGE MORETTON COMMISSAIRES PRISEURS À DROUOT Agrément 2004-508 – RCS Paris B 477 936 447. 15/17 passage Verdeau, 75009 Paris [email protected] • site : ka-mondo.fr Tél : 01 48 24 26 10 VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES HÔTEL DROUOT – SALLE 4 9, Rue Drouot – 75 009 Paris MERCREDI 30 OCTOBRE 2019 À 14H INCUNABLES & LIVRES DU XVIe SIÈCLE, LA PLUPART ILLUSTRÉS SCIENCES, MATHÉMATIQUES, ARCHITECTURE, RECUEILS DE GRAVURES DU XVIe AU XVIIIe SIÈCLES VOYAGES, ATLAS • PHOTOGRAPHIES ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES, ENVOIS AUTOGRAPHES SIGNÉS, ILLUSTRÉS DU XXe SIÈCLE Expositions publiques : Lundi 28 octobre 2019, de 11h à 18h. Mardi 29 octobre 2019, de 11h à 18h. Mercredi 30 octobre 2019, de 11h à 12h. Téléphone pendant l’exposition et la vente : 01 48 00 20 04 Le catalogue est disponible sur ka-mondo.fr, drouotonline.com, auction.fr, interenchères.com, bibliorare.com 1 1 COMMISSAIRE PRISEUR Élie MORHANGE BIBLIOGRAPHE Ludovic MIRAN Assisté de Maylis RIBETTES + 33 (0)6 07 17 37 20 [email protected] Lots 1 à 226, 239 à 298 et 300 à 317 En couverture lot 114, en 2e lot 98, en 3e lot 276 et en 4e lot 266 bis. Les lots Les lots précédés d'un astérisque * sont vendus par la SELARL KAPANDJI-MORHANGE par ordonnance du tribunal d'instance de Paris, et sont soumis aux frais judiciaires (12% H.T. -

Le Fonds D'archives De La Péniche Opéra

Cécile Auzolle ● Sylvain Labrousse ● Clara Roupie Le fonds d’archives de la Péniche Opéra Inventaire Mise en page de David Penot Version 11 | janvier 2018 Criham EA 4270 Introduction En 1975, Mireille Larroche crée la Péniche Théâtre, qui devient, en 1982, la Péniche Opéra, active dans le monde de l’art lyrique expérimental jusqu’en 2015. Cette institution témoigne de l’histoire du spectacle vivant entre 1975 et 2015, du dynamisme novateur des politiques culturelles et se singularise par la diversité de son parcours et des collaborations artistiques en présence. Les archives de cette compagnie représentent un matériau brut à explorer, à analyser, à faire parler, aussi bien dans une perspective d’histoire de la musique et de l’art lyrique – histoire du goût, monographies sur des œuvres, des compositeurs, des interprètes, des collaborateurs de spectacles… – d’histoire culturelle et d’études théâtrales. Elles constituent aussi une formidable banque de renseignements et matériaux artistiques pouvant servir à la recréation de spectacles. Projet de recherche et inventaire En décembre 2015, au moment de son départ en retraite et de la cession de la péniche à une autre compagnie, la POP (lieu des musiques mises en scène) Mireille Larroche lance un appel à ses amis et partenaires pour la valorisation des archives des Péniches -Théâtre et -Opéra. Cécile Auzolle (Criham/ IReMus) et Gilles Demonet (IReMus) puis Catherine Treilhou-Balaudé (Iret) construisent alors un projet de recherche destiné à aboutir à un colloque international, une publication et des manifestations culturelles en 2022, pour le quarantième anniversaire de la création de la Péniche Opéra.