The Continuing Influence of Greek and Roman Architecture Julia Walker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson A Thesis submitted by: Andre Weiss B. A. 1998 Supervisor: Dr. Gavin Stamp Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Architecture Mackintosh School of Architecture, The University of Glasgow September 1999 ProQuest N um ber: 13833922 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13833922 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1. The Previous Claims of an InfluentialRelationship ............................................18 2. An Exploration of the Individual Backgrounds of Thomson and Schinkel .............................................................................................................38 -

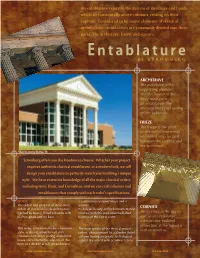

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC Lauren Webb July 2011 The architectural style of the original buildings at Bay Pines VA Medical Center is most often described as “Mediterranean Revival,” “Neo-Baroque,” or—somewhat rarely—“Churrigueresque.” However, with the shortage of similar buildings in the surrounding area and the chronological distance between the facility’s 1933 construction and Baroque’s popularity in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is often wondered how such a style came to be chosen for Bay Pines. This paper is an attempt to first, briefly explain the Baroque and Churrigueresque styles in Spain and Spanish America, second, outline the renewal of Spanish-inspired architecture in North American during the early 20th century, and finally, indicate some of the characteristics in the original buildings which mark Bay Pines as a Spanish Baroque- inspired building. The Spanish Baroque and Churrigueresque The Baroque style can be succinctly defined as “a style of artistic expression prevalent especially in the 17th century that is marked by use of complex forms, bold ornamentation, and the juxtaposition of contrasting elements.” But the beauty of these contrasting elements can be traced over centuries, particularly for the Spanish Baroque, through the evolution of design and the input of various cultures living in and interacting with Spain over that time. Much of the ornamentation of the Spanish Baroque can be traced as far back as the twelfth century, when Moorish and Arabesque design dominated the architectural scene, often referred to as the Mudéjar style. During the time of relative peace between Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Spain— the Convivencia—these Arabic designs were incorporated into synagogues and cathedrals, along with mosques. -

The Two-Piece Corinthian Capital and the Working Practice of Greek and Roman Masons

The two-piece Corinthian capital and the working practice of Greek and Roman masons Seth G. Bernard This paper is a first attempt to understand a particular feature of the Corinthian order: the fashioning of a single capital out of two separate blocks of stone (fig. 1).1 This is a detail of a detail, a single element of one of the most richly decorated of all Classical architec- tural orders. Indeed, the Corinthian order and the capitals in particular have been a mod- ern topic of interest since Palladio, which is to say, for a very long time. Already prior to the Second World War, Luigi Crema (1938) sug- gested the utility of the creation of a scholarly corpus of capitals in the Greco-Roman Mediter- ranean, and especially since the 1970s, the out- flow of scholarly articles and monographs on the subject has continued without pause. The basis for the majority of this work has beenformal criteria: discussion of the Corinthian capital has restedabove all onstyle and carving technique, on the mathematical proportional relationships of the capital’s design, and on analysis of the various carved components. Much of this work carries on the tradition of the Italian art critic Giovanni Morelli whereby a class of object may be reduced to an aggregation of details and elements of Fig. 1: A two-piece Corinthian capital. which, once collected and sorted, can help to de- Flavian period repairs to structures related to termine workshop attributions, regional varia- it on the west side of the Forum in Rome, tions,and ultimatelychronological progressions.2 second half of the first century CE (photo by author). -

Carl Gotthard Langhans 1732 - 1808

Carl Gotthard Langhans 1732 - 1808 Schriftenverzeichnis und Kommentar (mit Sekundärliteratur) Bearb. von Carola Aglaia Zimmermann, 2003 (Werke, deren Titel kursiv gesetzt sind, wurden eingesehen; in Zitaten wurde die Originalorthographie beibehalten) 1784 Practische Beiträge für den Geschmack in der Baukunst. 1. Theil. Von C. G. Langhans. Verlegt in Breslau. 1784. [2 S. Text mit eingefügter Radierung, 4 Tafeln mit Radierungen, 2°] Eingesehen: Berlin, Universität der Künste, Bibliothek: RP 0218. Das eingesehene Exemplar stammt aus der „Graf v. Lepellschen Bibliothek“ (Stempel und Ex Libris), alle Radierungen sind sorgfältig koloriert. Motto: „Tamen adspice, si quid et nos, quod cures proptium fecisse, loquamur. Hor. Epist. I XVII“ [Trotzdem bedenke, ob meine Worte Dir womöglich von Nutzen sein können.] Bemerkung: Keine weiteren Teile erschienen. Zusammenfassung: Objekt dieser Veröffentlichung ist ein Mausoleumsentwurf in Pyramidenform mit einem darin aufgestellten Grabmal. Auf den einzelnen Tafeln werden Aufriß, Schnitt und Grundriß der Pyramide, sowie der Aufriß des Grabmals, das darin zur Aufstellung kommen soll, gezeigt. Die Textseiten werden durch eine Radierung eröffnet: Auf der sandigen Anhöhe einer Insel steht das Mausoleum, von Bäumen hinterfangen. Das Bildmotto lautet: „Sic ego componi, versus in Ossa, velim. Tibl. III. V. 2“ [So möchte ich beigesetzt werden, verwandelt in Knochen.] Einleitend erläutert Langhans seinen Beweggrund, den Entwurf zu veröffentlichen: „Durch Versicherung verschiedener Kenner, und Liebhaber der Baukunst, daß die bisher von mir theils entworfene, theils würklich ausgeführte architectonischen Sachen durch öffentliche Herausgabe nützlich seyn könnten, nicht durch Zutrauen auf meine Werke selbst bewogen! wage ich es damit einen Versuch zu machen. Eine gütige Aufnahme dieser ersten Blätter wird entscheiden, ob ich in dieser Absicht fortfahren soll“ (S. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

•••••••• ••• •• • .. • ••••---• • • - • • ••••••• •• ••••••••• • •• ••• ••• •• • •••• .... ••• .. .. • .. •• • • .. ••••••••••••••• .. eo__,_.. _ ••,., .... • • •••••• ..... •••••• .. ••••• •-.• . PETER MlJRRAY . 0 • •-•• • • • •• • • • • • •• 0 ., • • • ...... ... • • , .,.._, • • , - _,._•- •• • •OH • • • u • o H ·o ,o ,.,,,. • . , ........,__ I- .,- --, - Bo&ton Public ~ BoeMft; MA 02111 The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance ... ... .. \ .- "' ~ - .· .., , #!ft . l . ,."- , .• ~ I' .; ... ..__ \ ... : ,. , ' l '~,, , . \ f I • ' L , , I ,, ~ ', • • L • '. • , I - I 11 •. -... \' I • ' j I • , • t l ' ·n I ' ' . • • \• \\i• _I >-. ' • - - . -, - •• ·- .J .. '- - ... ¥4 "- '"' I Pcrc1·'· , . The co11I 1~, bv, Glacou10 t l t.:• lla l'on.1 ,111d 1 ll01nc\ S t 1, XX \)O l)on1c111c. o Ponrnna. • The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance New Revised Edition Peter Murray 202 illustrations Schocken Books · New York • For M.D. H~ Teacher and Prie11d For the seamd edillo11 .I ltrwe f(!U,riucu cerurir, passtJgts-,wwbly thOS<' on St Ptter's awl 011 Pnlladfo~ clmrdses---mul I lr,rvl' takeu rhe t>pportrmil)' to itJcorporate m'1U)1 corrt·ctfons suggeSLed to nu.• byfriet1ds mu! re11iewers. T'he publishers lwvc allowed mr to ddd several nt•w illusrra,fons, and I slumld like 10 rltank .1\ Ir A,firlwd I Vlu,.e/trJOr h,'s /Jelp wft/J rhe~e. 711f 1,pporrrm,ty /t,,s 11/so bee,r ft1ke,; Jo rrv,se rhe Biblfogmpl,y. Fc>r t/Jis third edUfor, many r,l(lre s1m1II cluu~J!eS lwvi: been m"de a,,_d the Biblio,~raphy has (IJICt more hN!tl extet1si11ely revised dtul brought up to date berause there has l,een mt e,wrmc>uJ incretlJl' ;,, i111eres1 in lt.1lim, ,1rrhi1ea1JrP sittr<• 1963,. wlte-,r 11,is book was firs, publi$hed. It sh<>uld be 110/NI that I haw consistc11tl)' used t/1cj<>rm, 1./251JO and 1./25-30 to 111e,w,.firs1, 'at some poiHI betwt.·en 1-125 nnd 1430', .md, .stamd, 'begi,miug ilJ 1425 and rnding in 14.10'. -

The Sack of Rome and the Theme of Cultural Discontinuity

CHAPTER ONE THE SACK OF ROME AND THE THEME OF CULTURAL DISCONTINUITY i. Introduction The Sack of Rome had unmatched significance for contemporaries, and it triggered momentous cultural and intellectual transformations. It stands apart from the many other brutal conquests of the time, such as the sack of Prato fifteen years earlier, because Rome held a place of special prominence in the Renaissance imagination.1 This prominence was owed in part to the city's geographical position on the ruins of the ancient city of Rome, which provided an ever-pres ent visual reminder of its classical role sis caput mundi.2 Just as impor tant for contemporary observers, it stood at the center of Western Christendom: a position to which it had been restored in 1443, when Pope Eugenius IV returned the papacy to the Eternal City.3 In the ensuing decades, the Renaissance popes strove to rebuild the physical city and to enhance both the theoretical claim of the papacy to uni versal impenum and its actual political and ecclesiastical sway, which the recent schism had eroded. Modern historians, who have tended to confirm contemporaries' assessment of Rome's centrality in Renaissance European culture, have similarly viewed the events of 1527 as marking a critical turning point. The nineteenth-century German scholar Ferdinand Gregoro- vius chose the Imperial conquest of 1527 as the terminus ad quern for his monumental eight-volume history of Rome in the Middle Ages, 1 Eric Cochrane, Italy, 1530-1630 (London and New York, 1988), 9-10, also draws attention to this contrast. 2 On Renaissance Roman antiquarianism and archaeology, see the sources cited in Philip Jacks, The Antiquarian and the Myth of Antiquity: The Origins of Rome in Renaissance Thought (Cambridge, 1993); and idem, "The Simulachrum of Fabio Calvo: A View of Roman Architecture aWantka in 1527," Art Bulletin 72 (1990): 453-81. -

Palladio's Influence in America

Palladio’s Influence In America Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2008 marks the 500th anniversary of Palladio’s birth. We might ask why Americans should consider this to be a cause for celebration. Why should we be concerned about an Italian architect who lived so long ago and far away? As we shall see, however, this architect, whom the average American has never heard of, has had a profound impact on the architectural image of our country, even the city of Baltimore. But before we investigate his influence we should briefly explain what Palladio’s career involved. Palladio, of course, designed many outstanding buildings, but until the twentieth century few Americans ever saw any of Palladio’s works firsthand. From our standpoint, Palladio’s most important achievement was writing about architecture. His seminal publication, I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura or The Four Books on Architecture, was perhaps the most influential treatise on architecture ever written. Much of the material in that work was the result of Palladio’s extensive study of the ruins of ancient Roman buildings. This effort was part of the Italian Renaissance movement: the rediscovery of the civilization of ancient Rome—its arts, literature, science, and architecture. Palladio was by no means the only architect of his time to undertake such a study and produce a publication about it. Nevertheless, Palladio’s drawings and text were far more engaging, comprehendible, informative, and useful than similar efforts by contemporaries. As with most Renaissance-period architectural treatises, Palladio illustrated and described how to delineate and construct the five orders—the five principal types of ancient columns and their entablatures. -

Title: the Avant-Garde in the Architecture and Visual Arts of Post

1 Title: The avant-garde in the architecture and visual arts of Post-Revolutionary Mexico Author: Fernando N. Winfield Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 Mexico City / Portrait of an Architect with the City as Background. Painting by Juan O´Gorman (1949). Museum of Modern Art, Mexico. Commenting on an exhibition of contemporary Mexican architecture in Rome in 1957, the polemic and highly influential Italian architectural critic and historian, Bruno Zevi, ridiculed Mexican modernism for combining Pre-Columbian motifs with modern architecture. He referred to it as ‘Mexican Grotesque.’1 Inherent in Zevi’s comments were an attitude towards modern architecture that defined it in primarily material terms; its principle role being one of “spatial and programmatic function.” Despite the weight of this Modernist tendency in the architectural circles of Post-Revolutionary Mexico, we suggest in this paper that Mexican modernism cannot be reduced to such “material” definitions. In the highly charged political context of Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century, modern architecture was perhaps above all else, a tool for propaganda. ARCHITECTURE_MEDIA_POLITICS_SOCIETY Vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 1 2 In this political atmosphere it was undesirable, indeed it was seen as impossible, to separate art, architecture and politics in a way that would be a direct reflection of Modern architecture’s European manifestations. Form was to follow function, but that function was to be communicative as well as spatial and programmatic. One consequence of this “political communicative function” in Mexico was the combination of the “mural tradition” with contemporary architectural design; what Zevi defined as “Mexican Grotesque.” In this paper, we will examine the political context of Post-Revolutionary Mexico and discuss what may be defined as its most iconic building; the Central Library at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. -

An Analysis of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus As a Case of Etruscan Influence on Roman Religious Architec

HPS: The Journal of History & Political Science 5 Caput Mundi: An Analysis of the HPS: The Journal of History & Political Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus Science 2017, Vol. 5 1-12 as a Case of Etruscan Influence on © The Author(s) 2017 Roman Religious Architecture Mario Concordia York University, Canada While Roman architecture is often generalized as being primarily of Greek influence, there are important periods where other influences can be clearly identified. This paper considers the Etruscan, Greek, and Villanovan influence on Roman religious architecture through an examination of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maxmius, also known as the Capitolium, and argues that the temple is ultimately of primarily Etruscan influence. Introduction Religious temple architecture was a dynamic, evolving tradition throughout the entire span of Roman history. From its founding, customarily dated at 753 BCE with the mythical tale of Romulus and Remus, until the eventual fall of the Western Empire in the 5th century CE, temples were a central piece of the majesty of Roman architecture. But, like all construction fashion, what was dominant and popular in one period would inevitably change over time. As Becker indicates in his work, “Italic Architecture of the Earlier First Millennium BCE,” many scholars believe that Roman temple architecture is completely indebted to Greek advancements and influence, and that historians should be looking at Classic Greek models when considering Roman architecture,1 but this is hardly a complete answer. While it is true that Rome began to steer toward a more Hellenistic aesthetic some time around the Late Republic to Early Empire Period, there is an entire period before that which cannot be understood in this simple way.