Selected and Adapted by Rabbi Dov Karoll Quote from the Rosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3 Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50Am Mincha/Maariv 6:20Pm Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30Pm FRIDAY, OCTOBE

THE BAYIT BULLETIN MOTZEI SHABBAT, SEPTEMBER 21 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3 Maariv/Shabbat Ends (LLBM) 7:40pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50am Selichot Concert 9:45pm Mincha/Maariv 6:20pm Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22 Shacharit 8:30am FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4 Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:05, 7:50am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Candle Lighting 6:15pm Mincha/Maariv 6:25pm TUESDAY & WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24-25 Shacharit with Selichot 6:20, 7:50am SHABBAT SHUVA, OCTOBER 5 Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm Shacharit 7:00, 8:30am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Mincha 5:25pm MONDAY & THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23 & 26 Shabbat Shuva Drasha 5:55pm Maariv/Havdalah 7:16pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:15, 7:50am Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6 Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Shacharit with Selichot 8:30am FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27 Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:20, 7:50am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Candle Lighting 6:27pm Mincha 6:37pm MONDAY, OCTOBER 7 Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50am SHABBAT, SEPTEMBER 28 Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Shacharit 7:00am, 8:30am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Mincha 6:10pm Maariv/Shabbat Ends 7:28pm TUESDAY, OCTOBER 8 - EREV YOM KIPPUR SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 29: EREV ROSH HASHANA Shacharit with Selichot 6:35, 7:50am Shacharit w/ Selichot and Hatarat Nedarim 7:30am Mincha 3:30pm Candle Lighting 6:23pm Candle Lighting 6:09pm Mincha/Maariv 6:33pm Kol Nidre 6:10pm Fast Begins 6:27pm MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 30: ROSH HASHANA 1 Shacharit WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 9 - YOM KIPPUR Main Sanctuary and Social Hall -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

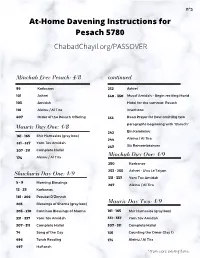

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Rosh Hashanah Ubhct Ubfkn

vbav atrk vkp, Rosh HaShanah ubhct ubfkn /UbkIe g©n§J 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, hear our voice. /W¤Ng k¥t¨r§G°h i¤r¤eo¥r¨v 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, give strength to your people Israel. /ohcIy ohH° jr© px¥CUb c,§ F 'UbFknUbh© ct¨ Avinu Malkeinu, inscribe us for blessing in the Book of Life. /vcIy v²b¨J Ubhkg J¥S©j 'UbFk©n Ubhc¨t Avinu Malkeinu, let the new year be a good year for us. 1 In the seventh month, hghc§J©v J¤s«jC on the first day of the month, J¤s«jk s¨j¤tC there shall be a sacred assembly, iIº,C©J ofk v®h§v°h a cessation from work, vgUr§T iIrf°z a day of commemoration /J¤s«et¨r§e¦n proclaimed by the sound v¨s«cg ,ftk§nkF of the Shofar. /U·Gg©, tO Lev. 23:24-25 Ub¨J§S¦e r¤J£t 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /c«uy o«uh (lWez¨AW) k¤J r¯b ehk§s©vk Ub²um±uuh¨,«um¦nC Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel (Shabbat v’shel) Yom Tov. We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, who hallows us with mitzvot and commands us to kindle the lights of (Shabbat and) Yom Tov. 'ok«ug¨v Qk¤n Ubh¥vO¡t '²h±h v¨T©t QUrC /v®Z©v i©n±Zk Ubgh°D¦v±u Ub¨n±H¦e±u Ub²h¡j¤v¤J Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, shehecheyanu v’kiy’manu v’higiyanu, lazman hazeh. -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Halachic Minyan”

Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shvat 5768 Intoduction 3 Minyan 8 Weekdays 8 Rosh Chodesh 9 Shabbat 10 The Three Major Festivals Pesach 12 Shavuot 14 Sukkot 15 Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah 16 Elul and the High Holy Days Selichot 17 High Holy Days 17 Rosh Hashanah 18 Yom Kippur 20 Days of Thanksgiving Hannukah 23 Arba Parshiot 23 Purim 23 Yom Ha’atzmaut 24 Yom Yerushalayim 24 Tisha B’Av and Other Fast Days 25 © Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal [email protected] [email protected] Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” 2 Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shevat 5768 “It is a positive commandment to pray every day, as it is said, You shall serve the Lord your God (Ex. 23:25). Tradition teaches that this “service” is prayer. It is written, serving Him with all you heart and soul (Deut. 2:13), about which the Sages said, “What is service of the heart? Prayer.” The number of prayers is not fixed in the Torah, nor is their format, and neither the Torah prescribes a fixed time for prayer. Women and slaves are therefore obligated to pray, since it is a positive commandment without a fixed time. Rather, this commandment obligates each person to pray, supplicate, and praise the Holy One, blessed be He, to the best of his ability every day; to then request and plead for what he needs; and after that praise and thank God for all the He has showered on him.1” According to Maimonides, both men and women are obligated in the Mitsva of prayer. -

Ezrat Avoteinu the Final Tefillah Before Engaging in the Shacharit

Ezrat Avoteinu The Final Tefillah before engaging in the Shacharit Amidah / Silent Meditative Prayer is Ezrat Avoteinu Atoh Hu Meolam – Hashem, You have been the support and salvation for our forefathers since the beginning….. The subject of this Tefillah is Geulah –Redemption, and it concludes with Baruch Atoh Hashem Ga’al Yisrael – Blessed are You Hashem, the Redeemer of Israel. This is in consonance with the Talmudic passage in Brachot 9B that instructs us to juxtapose the blessing of redemption to our silent Amidah i.e. Semichat Geulah LeTefillah. Rav Schwab zt”l in On Prayer pp 393 quotes the Siddur of Rav Pinchas ben R’ Yehudah Palatchik who writes that our Sages modeled our Tefillot in the style of the prayers of our forefathers at the crossing of the Reed Sea. The Israelites praised God in song and in jubilation at the Reed Sea, so too we at our moment of longing for redemption express song, praise and jubilation. Rav Pinchas demonstrates that embedded in this prayer is an abbreviated summary of our entire Shacharit service. Venatenu Yedidim – Our Sages instituted: 1. Zemirot – refers to Pesukei Dezimra 2. Shirot – refers to Az Yashir 3. Vetishbachot – refers to Yishtabach 4. Berachot – refers to Birkas Yotzair Ohr 5. Vehodaot – refers to Ahavah Rabbah 6. Lamelech Kel Chay Vekayam – refers to Shema and the Amidah After studying and analyzing the Shacharit service, we can see a strong and repetitive focus on our Exodus from Egypt. We say Az Yashir, we review the Exodus in Ezrat Avoteinu, in Vayomer, and Emet Veyatziv…. Why is it that we place such a large emphasis on the Exodus each and every day in the morning and the evening? The simple answer is because the genesis of our nation originates at the Exodus from Egypt. -

Halachic Minyan”

Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shvat 5768 Intoduction 3 Minyan 8 Weekdays 8 Rosh Chodesh 9 Shabbat 10 The Three Major Festivals Pesach 12 Shavuot 14 Sukkot 15 Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah 16 Elul and the High Holy Days Selichot 17 High Holy Days 17 Rosh Hashanah 18 Yom Kippur 20 Days of Thanksgiving Hannukah 23 Arba Parshiot 23 Purim 23 Yom Ha’atzmaut 24 Yom Yerushalayim 24 Tisha B’Av and Other Fast Days 25 © Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal [email protected] [email protected] Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” 2 Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shevat 5768 “It is a positive commandment to pray every day, as it is said, You shall serve the Lord your God (Ex. 23:25). Tradition teaches that this “service” is prayer. It is written, serving Him with all you heart and soul (Deut. 2:13), about which the Sages said, “What is service of the heart? Prayer.” The number of prayers is not fixed in the Torah, nor is their format, and neither the Torah prescribes a fixed time for prayer. Women and slaves are therefore obligated to pray, since it is a positive commandment without a fixed time. Rather, this commandment obligates each person to pray, supplicate, and praise the Holy One, blessed be He, to the best of his ability every day; to then request and plead for what he needs; and after that praise and thank God for all the He has showered on him.1” According to Maimonides, both men and women are obligated in the Mitsva of prayer. -

PESACH HOLIDAY SCHEDULE 2020 Jewishroc “PRAY-FROM-HOME” April 8 – April 16

PESACH HOLIDAY SCHEDULE 2020 JewishROC “PRAY-FROM-HOME” April 8 – April 16 During these times of social distancing, we encourage everyone to maintain the same service times AT HOME as if services were being held at JewishROC. According to Jewish Law under compelling circumstances, a person who cannot participate in the community service should make every effort to pray at the same time as when the congregation has their usual services. (All page numbers provided below are for the Artscroll Siddur or Chumash used at JewishROC) Deadline for Sale of Chametz Wed. April 1, 5:00 p.m. (Forms must be emailed to [email protected]) Search for Chametz Tues. April 7, 8:12 p.m. – see Siddur page 654 Burning/Disposal of Chametz Wed. April 8, 10:36 a.m. at the latest; recite the third paragraph on page 654 of the Siddur Siyyum for First Born: Tractate Sotah Wed. April 8, 9:00 a.m. - Held Remotely: Register no later than April 1st by sending your Skype address to [email protected]. Wednesday, April 8: Erev Pesach 1st Seder 7:15 a.m. Morning service/Shacharit: Siddur pages 16-118; 150-168. 9:00 a.m. Siyyum for first born; Register no later than April 1st by sending your Skype address to [email protected]. 10:30 a.m. Burning/disposal of Chametz; see page 654 of Artscroll Siddur. Don’t forget to recite the Annulment of the Chametz (third paragraph) 7:15 p.m. Afternoon Service/Mincha: Pray the Daily Minchah, Siddur page 232-248; Conclude with Aleinu 252-254 7:30 p.m.