British World War Two Films 1945-65: Catharsis Or National Regeneration?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Role of the Archives in the Future

… You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time…” Abraham Lincoln ( 1809 – 1865 ) FACTS AND FICTION- ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE HISTORICAL EVENTS AND TELEVISION AND FILM PRODUCTIONS Media Archeology Movies and television productions are released and transmitted each year dealing with historical events or public personalities like politicians , military leaders, revolutionaries, and people with a record of special achievemments. The aim of my presentation is to make you aware of different possibilities in reusing archival footage in movies. It is my intention to inform you about the importance of the audiovisual archives and how to reuse transmitted programmes or real shots of life in new productions. It is not my intention to evaluate real shots in historical movies and to report about facts and fiction in those films. The subject is dealt with in the book called: PAST IMPERFECT. History According to the Movies. 1995, and my own paper on the same subject: HISTORY AND MOVIES: An evaluation of the information of historical events, of international known personalities and of famous sites and buildings describes in movies. External links: ( Contact: http://www.baacouncil.org/ or [email protected] for copy of the paper) Television companies should be proud of their collections of transmitted programmes. Because I have worked for televison archive for about 29 years I have viewed a lot of television programmes and movies. Some years ago I started to question the reuse of transmitted television programmes and also the active reuse of news in new productions. -

Inside the Covert War Against Terrorism's Money Masters, by Nitsana Darshan- Leitner and Samuel M

Annotated List of New Resources at The Kaufman Silverberg Library January 2018 For our searchable catalogue go to www.winnipegjewishlibrary.ca Our Facebook Page www.fb.com/kaufmansilverberglibrary Adult Judaic Non Fiction Harpoon: inside the covert war against terrorism's money masters, by Nitsana Darshan- Leitner and Samuel M. Katz. Offers a gripping story of the Israeli-led effort, now joined by the Americans, to choke off the terrorists' oxygen supply, money, via unconventional warfare. Call number: Z 953.23 DAR Judaic Fiction The luminous heart of Jonah S., by Gina B. Nahai. The Soleymans, an Iranian Jewish family, are tormented for decades by Raphael's Son, a crafty and unscrupulous financier who has futilely claimed to be an heir to the family's fortune. Forty years later in contemporary Los Angeles, Raphael's Son has nearly achieved his goal--until he suddenly disappears, presumed by many to have been murdered. Call number: Z FIC NAH General Non-Fiction Survival skills of the Native Americans: hunting, trapping, woodwork and more, edited by Stephen Brennan. A practical guide to the techniques that have made the indigenous people of North America revered for their mastery of the wilderness. Readers can replicate outdoor living by trying a hand at making rafts and canoes, constructing tools, and living off the land. Call number: 970.4 BRE General Fiction The buried giant, by Kazuo Ishiguro. The Buried Giant begins as a couple set off across a troubled land of mist and rain in the hope of finding a son they have not seen in years. -

Terror, Trauma and the Eye in the Triangle: the Masonic Presence in Contemporary Art and Culture

TERROR, TRAUMA AND THE EYE IN THE TRIANGLE: THE MASONIC PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART AND CULTURE Lynn Brunet MA (Hons) Doctor of Philosophy November 2007 This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this Thesis is the result of original research, which was completed subsequent to admission to candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signature: ……………………………… Date: ………………………….. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been generously supported, in terms of supervision, teaching relief and financial backing by the University of Newcastle. Amongst the individuals concerned I would like to thank Dr Caroline Webb, my principal supervisor, for her consistent dedication to a close reading of the many drafts and excellent advice over the years of the thesis writing process. Her sharp eye for detail and professional approach has been invaluable as the thesis moved from the amorphous, confusing and sometimes emotional early stages into a polished end product. I would also like to thank Dr Jean Harkins, my co- supervisor, for her support and feminist perspective throughout the process and for providing an accepting framework in which to discuss the difficult material that formed the subject matter of the thesis. -

What Are They Doing There? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1989 What are they doing there? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gehman, William Geoffrey, "What are they doing there? :" (1989). Theses and Dissertations. 4957. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/4957 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • ,, WHAT ARE THEY DOING THERE?: ACTING AND ANALYZING SAMUEL BECKETT'S HAPPY DAYS by William Geoffrey Gehman A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University 1n Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts 1n English Lehigh University 1988 .. This thesis 1S accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. (date) I Professor 1n Charge Department Chairman 11 ACD01fLBDGBNKNTS ., Thanks to Elizabeth (Betsy) Fifer, who first suggested Alan Schneider's productions of Samuel Beckett's plays as a thesis topic; and to June and Paul Schlueter for their support and advice. Special thanks to all those interviewed, especially Martha Fehsenfeld, who more than anyone convinced the author of Winnie's lingering presence. 111 TABLB OF CONTBNTS Abstract ...................•.....••..........•.•••••.••.••• 1 ·, Introduction I Living with Beckett's Standards (A) An Overview of Interpreting Winnie Inside the Text ..... 3 (B) The Pros and Cons of Looking for Clues Outside the Script ................................................ 10 (C) The Play in Context .................................. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson

23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson Save 0 Filmography Show less 1971 Creatures the World Forgot Special Effects 1969 Desert Journey Special Effects 1969 Autokill Special Effects 1966 The Heroes of Telemark [Special Effects] 1965 The Secret of Blood Island Special Effects 1965 The Brigand of Kandahar Special Effects 1964 The Long Ships Special Effects 1964 The Gorgon Special Effects 1962 In Search of the Castaways Special Effects 1960 The Brides of Dracula Special Effects 1959 Too Many Crooks [Special Processes] 1959 North West Frontier Special Effects 1959 The Hound of the Baskervilles Special Effects 1959 Ferry to Hong Kong Special Effects 1958 Dracula Special Effects 1957 The Steel Bayonet Special Effects 1957 Campbell's Kingdom Special Effects 1956 The Ladykillers Special Effects 1956 House of Secrets Special Processes (uncredited) 1956 Reach for the Sky Models (uncredited) 1955 Out of the Clouds Special Effects 1955 The Ship That Died of Shame Special Effects 1955 The Night My Number Came Up Special Effects 1955 Touch and Go Special Effects 1954 The Love Lottery Special Effects 1954 The 'Maggie' Special Effects https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 1/2 23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI 1953 The Cruel Sea Special Effects 1953 The Titfield Thunderbolt Special Effects 1952 His Excellency Special Effects 1952 Mandy [Special Effects] 1952 I Believe in You Special Effects (uncredited) 1952 The Gentle Gunman Special Effects 1952 Secret People Special Effects 1951 Pool of London Special Effects 1951 The Man in the White Suit Special Effects 1951 The Lavender Hill Mob Special Effects 1950 Cage of Gold Special Effects 1950 Dance Hall Special Effects 1950 The Magnet Special Effects 1949 Kind Hearts and Coronets Special Effects 1949 Train of Events Special Effects 1949 Whisky Galore! Special Effects 1948 Scott of the Antarctic Special Effects 1947 The October Man [Stage Effects] [Model Miniatures] 1947 Black Narcissus [Synthetic Pictorial Effects] https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 2/2. -

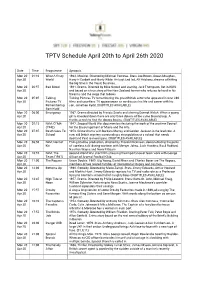

TPTV Schedule April 20Th to April 26Th 2020

TPTV Schedule April 20th to April 26th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 20 01:10 What A Crazy 1963. Musical. Directed by Michael Carreras. Stars Joe Brown, Susan Maughan, Apr 20 World Harry H Corbett and Marty Wilde. An East End lad, Alf Hitchens, dreams of hitting the big time in the music business. Mon 20 02:55 Bad Blood 1981. Drama. Directed by Mike Newell and starring Jack Thompson. Set in WW2 Apr 20 and based on a true story of the New Zealand farmer who refuses to hand in his firearms and the siege that follows. Mon 20 05:05 Talking Talking Pictures TV remembering the great British actor who appeared in over 240 Apr 20 Pictures TV films and countless TV appearances as we discuss his life and career with his Remembering son, Jonathan Kydd. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Sam Kydd Mon 20 06:00 Emergency 1962. Drama directed by Francis Searle and starring Dermot Walsh. When a young Apr 20 girl is knocked down there are only three donors of the same blood group. A frantic search to find the donors begins. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 20 07:15 IWM: CEMA 1942. Second World War documentary featuring the work of the wartime Council Apr 20 (1942) for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. Mon 20 07:35 Death Goes To 1953. Crime drama with Barbara Murray and Gordon Jackson in the lead role. A Apr 20 School rare, old British mystery surrounding a strangulation at a school that needs Scotland Yard to investigate. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 20 08:50 IWM: Next of Ealing Studios production, directed by Thorold Dickinson, demonstrating the perils Apr 20 Kin of 'careless talk' during wartime, with Mervyn Johns, Jack Hawkins, Basil Radford, Naunton Wayne and Nova Pilbeam. -

WHYTE's Movie Posters 31 May 2014 Results

, WHYTE S SINCE 1783 MOVIE POSTERS SATURDAY 31 MAY 2014 MOVIEA SinglePOST Owner CollectionERS SATURDAY 31 MAY 2014 VIEWING At our galleries 38 Molesworth Street, Dublin 2 Wednesday 28 May 10am to 5pm Thursday 29 May 10am to 7pm Friday 30 May 10am to 7pm Saturday 31 May 10am to 12 noon AUCTION Saturday 31 May at 12 noon The Freemasons Hall, 17 Molesworth Street, Dublin 2 ENQUIRIES Whyte's 38 Molesworth Street Dublin 2 Tel: 01 676 2888 Fax: 01 676 2880 E-mail: [email protected] BIDS Whyte's 38 Molesworth Street Dublin 2 Tel: 01 676 2888 Fax: 01 676 2880 E-mail: [email protected] Live bidding and on-line bids: www.whytes.ie Whyte’s Auction App WEBSITES now available for free download whytes.ie whytes.com Opposite: Ex lot 5, Gone With The Wind (detail) DESIGN: DES KIELY DESIGN PHOTOGRAPHY: GILLIAN BUCKLEY PRINTING: BRUNSWICK PRESS LTD. , © COPYRIGHT 2014 WHYTE AND SONS AUCTIONEERS LTD. WHYTE S ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SINCE 1783 TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE NOTICE Whyte & Sons Auctioneers Limited, trading as Whyte’s, exercises all (c) If any lot sold at this auction is subsequently proved to be a reasonable care to ensure that all descriptions are reliable and accurate, “deliberate forgery”, Whyte’s will cancel the sale and refund to the buyer and that each item is genuine unless the contrary is indicated. However, the total amount paid by the buyer for the item, in the currency of the the descriptions are not intended to be, are not and are not to be taken original sale. -

Talking Pictures TV Highlights for Week Beginning Mon 21St December 2020 SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Christmas Week

Talking Pictures TV Highlights for week beginning www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Mon 21st December 2020 SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Christmas Week Monday 21st December 7:25am Tuesday 22nd December 4:20pm Escape By Night (1953) Man on the Run (1949) Crime. Director: John Gilling. Crime Drama. Director: Lawrence Stars: Bonar Colleano, Sid James, Huntington. Stars: Valentine Dyall, Andrew Ray, Ted Ray, Simone Silva. Derek Farr and Leslie Perrins. Having An ace reporter with a drinking deserted the army, Peter Burdon is problem tracks a gangster on the run. continually on the run. Monday 21st December 9am and Tuesday 22nd December 6:50pm Wednesday 23rd December 4:30pm The Night My Number Came Up Stars, Cars & Guitars (1955) Talking Christmas – Mystery. Director: Leslie Norman. a Talking Pictures TV Exclusive! Stars: Michael Redgrave, Sheila Sim, Singer Tony Hadley, legendary Denholm Elliott and Alexander Knox. rock guitarist Jim Cregan and The fate of a military aircraft may broadcaster Alex Dyke bring their depend on a prophetic nightmare. Stars, Cars, Guitars show to Talking Tuesday 22nd December 9pm Pictures TV for a Christmas special. Shout at the Devil (1976) They’re joined by guests Marty and War. Director: Peter R. Hunt. Kim Wilde, Suzi Quatro and Mike Read Stars: Lee Marvin, Roger Moore, for a nostalgic look back at Christmas Barbara Parkins, Ian Holm, in the fifties and sixties as well as live Reinhard Kolldehoff. An American performances and festive fun. ex-military man and a British aristocrat are partners in the ivory Monday 21st December 12:15pm trade. On the eve of World War I, and Christmas Eve 6:10am they join battle against a German Scrooge (1935) Commander and his men. -

Fall/Winter 2018

FALL/WINTER 2018 Yale Manguel Jackson Fagan Kastan Packing My Library Breakpoint Little History On Color 978-0-300-21933-3 978-0-300-17939-2 of Archeology 978-0-300-17187-7 $23.00 $26.00 978-0-300-22464-1 $28.00 $25.00 Moore Walker Faderman Jacoby Fabulous The Burning House Harvey Milk Why Baseball 978-0-300-20470-4 978-0-300-22398-9 978-0-300-22261-6 Matters $26.00 $30.00 $25.00 978-0-300-22427-6 $26.00 Boyer Dunn Brumwell Dal Pozzo Minds Make A Blueprint Turncoat Pasta for Societies for War 978-0-300-21099-6 Nightingales 978-0-300-22345-3 978-0-300-20353-0 $30.00 978-0-300-23288-2 $30.00 $25.00 $22.50 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS 1 General Interest COVER: From Desirable Body, page 29. General Interest 1 The Secret World Why is it important for policymakers to understand the history of intelligence? Because of what happens when they don’t! WWI was the first codebreaking war. But both Woodrow Wilson, the best educated president in U.S. history, and British The Secret World prime minister Herbert Asquith understood SIGINT A History of Intelligence (signal intelligence, or codebreaking) far less well than their eighteenth-century predecessors, George Christopher Andrew Washington and some leading British statesmen of the era. Had they learned from past experience, they would have made far fewer mistakes. Asquith only bothered to The first-ever detailed, comprehensive history Author photograph © Justine Stoddart. look at one intercepted telegram. It never occurred to of intelligence, from Moses and Sun Tzu to the A conversation Wilson that the British were breaking his codes. -

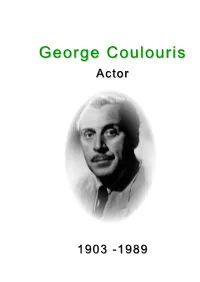

The Booklet That Accompanied the Exhibition, With

GGeeoorrggee CCoouulloouurriiss AAccttoorr 11990033 --11998899 George Coulouris - Biographical Notes 1903 1st October: born in Ordsall, son of Nicholas & Abigail Coulouris c1908 – c1910: attended a local private Dame School c1910 – 1916: attended Pendleton Grammar School on High Street c1916 – c1918: living at 137 New Park Road and father had a restaurant in Salisbury Buildings, 199 Trafford Road 1916 – 1921: attended Manchester Grammar School c1919 – c1923: father gave up the restaurant Portrait of George aged four to become a merchant with offices in Salisbury Buildings. George worked here for a while before going to drama school. During this same period the family had moved to Oakhurst, Church Road, Urmston c1923 – c1925: attended London’s Central School of Speech and Drama 1926 May: first professional stage appearance, in the Rusholme (Manchester) Repertory Theatre’s production of Outward Bound 1926 October: London debut in Henry V at the Old Vic 1929 9th Dec: Broadway debut in The Novice and the Duke 1933: First Hollywood film Christopher Bean 1937: played Mark Antony in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre production of Julius Caesar 1941: appeared in the film Citizen Kane 1950 Jan: returned to England to play Tartuffe at the Bristol Old Vic and the Lyric Hammersmith 1951: first British film Appointment With Venus 1974: played Dr Constantine to Albert Finney’s Poirot in Murder On The Orient Express. Also played Dr Roth, alongside Robert Powell, in Mahler 1989 25th April: died in Hampstead John Koulouris William Redfern m: c1861 Louisa Bailey b: 1832 Prestbury b: 1842 Macclesfield Knutsford Nicholas m: 10 Aug 1902 Abigail Redfern Mary Ann John b: c1873 Stretford b: 1864 b: c1866 b: c1861 Greece Sutton-in-Macclesfield Macclesfield Macclesfield d: 1935 d: 1926 Urmston George Alexander m: 10 May 1930 Louise Franklin (1) b: Oct 1903 New York Salford d: April 1989 d: 1976 m: 1977 Elizabeth Donaldson (2) George Franklin Mary Louise b: 1937 b: 1939 Where George Coulouris was born Above: Trafford Road with Hulton Street going off to the right.