Foundation Document Olympic National Park Washington September 2017 Foundation Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities

NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN THE FIRST 10 YEARS (1994–2003) Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities Lita P. Buttolph, William Kay, Susan Charnley, Cassandra Moseley, and Ellen M. Donoghue General Technical Report United States Forest Pacific Northwest PNW-GTR-679 Department of Service Research Station July 2006 Agriculture The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all pro- grams.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness: You can help W a s h i n g t o n S t a t e P a r k s A necessary prohibition Join us in safeguarding winter recreation: Each year, more and more people are riding snowmobiles • When riding in a new area, obtain a map. into designated Wilderness areas, which is a concern for • Familiarize yourself with Wilderness land managers, the public and many snowmobile groups. boundaries, and don’t cross them. This may be happening for a variety of reasons: many • Carry the message to clubs, groups and friends. snowmobilers may not know where the Wilderness boundaries are or may not realize the area is closed. For more information about snowmobiling opportunities or Wilderness areas, please contact: Wilderness…a special place Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (360) 902-8500 Established by Congress through the Wilderness Washington State Snowmobile Association (800) 784-9772 Act of 1964, “Wilderness” is a special land designation North Cascades National Park (360) 854-7245 within national forests and certain other federal lands. Colville National Forest (509) 684-7000 These areas were designated so that an untouched Gifford Pinchot National Forest (360) 891-5000 area of our wild lands could be maintained in a natural Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest (425) 783-6000 state. Also, they were set aside as places where people Mt. Rainier National Park (877) 270-7155 could get away from the sights and sounds of modern Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest (509) 664-9200 civilization and where elements of our cultural history Olympic National Forest (360) 956-2402 could be preserved. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization And

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98503 In Reply Refer To: AUG 1 6 2011 13410-2011-F-0141 13410-2010-F-0175 Daniel M. Mathis, Division Adnlinistrator Federal Highway Administration ATIN: Jeff Horton Evergreen Plaza Building 711 Capitol Way South, Suite 501 Olympia, Washington 98501-1284 Michelle Walker, Chief, Regulatory Branch Seattle District, Corps of Engineers ATIN: Rebecca McAndrew P.O. Box 3755 Seattle, Washington 98124-3755 Dear Mr. Mathis and Ms. Walker: This document transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion (Opinion) based on our review of the proposed State Route 20, Skagit River Emergency Bank Stabilization and Chronic Environmental Deficiency Project in Skagit County, Washington, and its effects on the bull trout (Salve linus conjluentus), marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina), and designated bull trout critical habitat, in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) (Act). Your requests for initiation of formal consultation were received on February 3, 2011, and January 19,2010. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - Seattle District (Corps) provided information in support of "may affect, likely to adversely affect" determinations for the bull trout and designated bull trout critical habitat. On April 13 and 14, 2011, the FHWA and Corps gave their consent for addressing potential adverse effects to the bull trout and bull trout critical habitat with a single Opinion. -

Backcountry Campsites at Waptus Lake, Alpine Lakes Wilderness

BACKCOUNTRY CAMPSITES AT WAPTUS LAKE, ALPINE LAKES WILDERNESS, WASHINGTON: CHANGES IN SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTED AREAS, AND USE OVER TIME ___________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Resource Management ___________________________________________________ by Darcy Lynn Batura May 2011 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Darcy Lynn Batura Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Karl Lillquist, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Anthony Gabriel ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Cottrell ______________ _________________________________________ Resource Management Program Director ______________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT BACKCOUNTRY CAMPSITES AT WAPTUS LAKE, ALPINE LAKES WILDERNESS, WASHINGTON: CHANGES IN SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTED AREAS, AND USE OVER TIME by Darcy Lynn Batura May 2011 The Wilderness Act was created to protect backcountry resources, however; the cumulative effects of recreational impacts are adversely affecting the biophysical resource elements. Waptus Lake is located in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, the most heavily used wilderness in Washington -

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future As more and more states are incorporating projections of sea-level rise into coastal planning efforts, the states of California, Oregon, and Washington asked the National Research Council to project sea-level rise along their coasts for the years 2030, 2050, and 2100, taking into account the many factors that affect sea-level rise on a local scale. The projections show a sharp distinction at Cape Mendocino in northern California. South of that point, sea-level rise is expected to be very close to global projections; north of that point, sea-level rise is projected to be less than global projections because seismic strain is pushing the land upward. ny significant sea-level In compliance with a rise will pose enor- 2008 executive order, mous risks to the California state agencies have A been incorporating projec- valuable infrastructure, devel- opment, and wetlands that line tions of sea-level rise into much of the 1,600 mile shore- their coastal planning. This line of California, Oregon, and study provides the first Washington. For example, in comprehensive regional San Francisco Bay, two inter- projections of the changes in national airports, the ports of sea level expected in San Francisco and Oakland, a California, Oregon, and naval air station, freeways, Washington. housing developments, and sports stadiums have been Global Sea-Level Rise built on fill that raised the land Following a few thousand level only a few feet above the years of relative stability, highest tides. The San Francisco International Airport (center) global sea level has been Sea-level change is linked and surrounding areas will begin to flood with as rising since the late 19th or to changes in the Earth’s little as 40 cm (16 inches) of sea-level rise, a early 20th century, when climate. -

Keeping It Wild in the National Park Service

Wilderness Stewardship Division National Park Service Wilderness Stewardship Program U.S. Department of the Interior Keeping It Wild in the National Park Service A USER GUIDE TO INTEGRATING WILDERNESS CHARACTER INTO PARK PLANNING, MANAGEMENT, AND MONITORING Keeping it Wild in the National Park Service A User Guide to Integrating Wilderness Character into Park Planning, Management, and Monitoring National Park Service | U.S. Department of the Interior Wilderness Stewardship Division | Wilderness Stewardship Program January 2014 Cover photos: (Top) NPS/Suzy Stutzman, Great Sand Dunes Wilderness, Great Sand Dunes National Park (Left) NPS/Peter Landres, recommended wilderness, Canyonlands National Park (Right) NPS/Peter Landres, recommended wilderness, Cedar Breaks National Monument KEEPING IT WILD IN THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE A USER GUIDE TO INTEGRATING WILDERNESS CHARACTER INTO PARK PLANNING, MANAGEMENT, AND MONITORING Developed by the National Park Service Wilderness Character Integration Team with funding and support from the NPS Office of Park Planning and Special Studies and the Wilderness Stewardship Division A Companion Document to the 2014 Wilderness Stewardship Plan Handbook: Planning to Preserve Wilderness Character WASO 909/121797; January 2014 EXECUTIVE SummARY This User Guide was developed to help National Park Service (NPS) staff effectively and efficiently fulfill the mandate from the 1964 Wilderness Act and NPS policy to “preserve wilderness character” now and into the future. This mandate applies to all congressionally designated wilderness and other park lands that are, by policy, managed as wilderness, including eligible, potential, proposed, or recommended wilderness. This User Guide builds on the ideas in Keeping It Wild: An Interagency Strategy to Monitor Trends in Wilderness Character Across the National Wilderness Preservation System (Landres and others 2008). -

A Brief History of the Umatilla National Forest

A BRIEFHISTORYOFTHE UMATILLA NATIONAL FOREST1 Compiled By David C. Powell June 2008 1804-1806 The Lewis and Clark Expedition ventured close to the north and west sides of the Umatilla National Forest as they traveled along the Snake and Columbia rivers. As the Lewis & Clark party drew closer to the Walla Walla River on their return trip in 1806, their journal entries note the absence of firewood, Indian use of shrubs for fuel, abundant roots for human consumption, and good availability of grass for horses. Writing some dis- tance up the Walla Walla River, William Clark noted that “great portions of these bottoms has been latterly burnt which has entirely destroyed the timbered growth” (Robbins 1997). 1810-1840 This 3-decade period was a period of exploration and use by trappers, missionaries, natu- ralists, and government scientists or explorers. William Price Hunt (fur trader), John Kirk Townsend (naturalist), Peter Skene Ogden (trap- per and guide), Thomas Nuttall (botanist), Reverend Samuel Parker (missionary), Marcus and Narcissa Whitman (missionaries), Henry and Eliza Spaulding (missionaries), Captain Benjamin Bonneville (military explorer), Captain John Charles Fremont (military scientist), Nathaniel J. Wyeth (fur trader), and Jason Lee (missionary) are just a few of the people who visited and described the Blue Mountains during this era. 1840-1859 During the 1840s and 1850s – the Oregon Trail era – much overland migration occurred as settlers passed through the Blue Mountains on their way to the Willamette Valley (the Oregon Trail continued to receive fairly heavy use until well into the late 1870s). The Ore- gon Trail traversed the Umatilla National Forest. -

Umatilla National Forest 2019 Personal-Use Firewood Maps Attachment–Part 2 (Part 1 Is Your Permit Form)

United States Department of Agriculture Umatilla National Forest 2019 Personal-Use Firewood Maps Attachment–Part 2 (Part 1 is your Permit Form) Is Today a Cut Day? INSIDE......... It's Your Responsibility to Important News for 2019.................................2 Find Out Before You Head Out! Heppner District Maps................................5-6 An updated recorded message will let you know if firewood North Fork John Day District Maps.…..............6-7 cutting is allowed, restricted to certain times of the day, or Walla Walla District Maps.............................8-10 closed completely due to hot, dry weather conditions. Pomeroy District Maps...……..….......…....11-12 21" Ruler for gauging diameter............................8-9 Call Toll-Free 2019 Firewood Season Calendar……...….….13 1-877-958-9663 Where to call for information .…......................16 Page 2 Umatilla National Forest's 2019 Program GENERAL INFORMATION: COMMERCIAL FIREWOOD: To purchase a firewood permit, you must be 18 years of age or older and All commercial activities on National Forest System Lands require a present a government-issued photo ID. commercial permit. If you wish to cut and sell firewood commercially, you must purchase a commercial firewood permit through the local The minimum cost for a personal-use firewood permit is $20, which buys Ranger District office for your area of interest. District contact four-cords. Anything over four cords will cost an additional $5 per cord. information is provided on the back page of this guide. Each household is allowed a maximum limit of 12 cords per year. HEPPNER DISTRICT OFFERS LIVE JUNIPER CUTTING: Firewood permits are available at all Umatilla National Forest Offices and at several local vendors. -

Geologic History of Siletzia, a Large Igneous Province in the Oregon And

Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Wells, R., Bukry, D., Friedman, R., Pyle, D., Duncan, R., Haeussler, P., & Wooden, J. (2014). Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot. Geosphere, 10 (4), 692-719. doi:10.1130/GES01018.1 10.1130/GES01018.1 Geological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Downloaded from geosphere.gsapubs.org on September 10, 2014 Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Ray Wells1, David Bukry1, Richard Friedman2, Doug Pyle3, Robert Duncan4, Peter Haeussler5, and Joe Wooden6 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025-3561, USA 2Pacifi c Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, 6339 Stores Road, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1680 East West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, 104 CEOAS Administration Building, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-5503, USA 5U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4626, USA 6School of Earth Sciences, Stanford University, 397 Panama Mall Mitchell Building 101, Stanford, California 94305-2210, USA ABSTRACT frames, the Yellowstone hotspot (YHS) is on southern Vancouver Island (Canada) to Rose- or near an inferred northeast-striking Kula- burg, Oregon (Fig. -

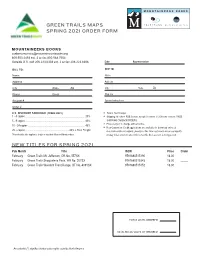

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Space Use and Seasonal Movement of Isolated Mountain Goat Populations in the North Cascades, WA

Space Use and Seasonal Movement of Isolated Mountain Goat Populations in the North Cascades, WA Jennifer Sevigny ( [email protected] ) Amanda Summers: Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, Natural Resources Department, 22712 6th Avenue NE, Arlington, WA 98223 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1839-3872 Amanda Summers Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians Emily George-Wirtz Sauk-Suiattle Tribe Research Keywords: mountain goat, home range, spatial overlap, utilization distribution overlap index, seasonal range, Cascades Posted Date: October 5th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-84165/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/25 Abstract Background: The spatial distribution and seasonal movement patterns of isolated populations of mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) in the North Cascade range of Washington State is not fully understood. Determining harvest potential in these populations is challenging without a clear understanding of spatiotemporal movement, space use, and spatial overlap. Mountain goat populations in the North Cascades are fragmented and many have declined considerably from historic estimates. Identication of harvestable populations requires a clear understanding of population size, distribution, and movement. We investigated the population trends and spatial distribution of mountain goats in the Boulder River North Harvest Area in Boulder River Wilderness of Washington State. Methods: We reviewed recent mountain goat population estimates and used Global Positioning System collar data to determine year-round and seasonal home range distributions, spatial overlap within these ranges, and proximity of mountain goats to roads and trails. Results: We found 2 populations of mountain goats inhabiting the Whitehorse and Three Fingers Mountains in the Boulder River North Harvest Area.