The Eastern Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE SEES RECORD VISITATION for 2020 Lodging Reservation System Now Open for 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 1, 2021 Contact: Beth Saboe Senior Media and Government Relations Manager Phone: 406-600-4906 Email: [email protected] AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE SEES RECORD VISITATION FOR 2020 Lodging reservation system now open for 2021 American Prairie Reserve experienced a surge of visitation in 2020, recording more people staying overnight at its facilities than any previous year. Overnight reservations last year were up nearly 200 percent compared to 2019. The uptick in visitation was driven in part by people seeking respite outdoors from the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, and came despite having only 40 percent of the Reserve’s camping and lodging inventory available due to COVID-19 precautions. According to American Prairie’s Director of Recreation and Public Access Mike Kautz, 665 reservations were recorded in 2020 from the Reserve’s three huts, and two campgrounds. In comparison, there were 232 reservations recorded in 2019. A reservation is defined as a group reserving one unit of lodging (campsite, hut or cabin), and not a count of individual visitors. Kautz says each reservation had an average group size of 4 people. In addition, the majority of people visiting the Reserve are Montanans. In 2020, more than 88% of the reservations for American Prairie’s hut system and more than 50% of reservations for the campgrounds came from state residents. Kautz says this growing interest suggests visitors should consider making reservations earlier this year. “Word of this pretty unique prairie experience we offer is quickly spreading,” said Kautz. “We fully expect our reservation inventory to fill up quickly this year so anyone who is curious about the lodging options shouldn’t wait too long.” Reservations for American Prairie’s 2021 visitation season are now being accepted, as of February 1. -

Chapter 6: Federalists and Republicans, 1789-1816

Federalists and Republicans 1789–1816 Why It Matters In the first government under the Constitution, important new institutions included the cabinet, a system of federal courts, and a national bank. Political parties gradually developed from the different views of citizens in the Northeast, West, and South. The new government faced special challenges in foreign affairs, including the War of 1812 with Great Britain. The Impact Today During this period, fundamental policies of American government came into being. • Politicians set important precedents for the national government and for relations between the federal and state governments. For example, the idea of a presidential cabinet originated with George Washington and has been followed by every president since that time • President Washington’s caution against foreign involvement powerfully influenced American foreign policy. The American Vision Video The Chapter 6 video, “The Battle of New Orleans,” focuses on this important event of the War of 1812. 1804 • Lewis and Clark begin to explore and map 1798 Louisiana Territory 1789 • Alien and Sedition • Washington Acts introduced 1803 elected • Louisiana Purchase doubles president ▲ 1794 size of the nation Washington • Jay’s Treaty signed J. Adams Jefferson 1789–1797 ▲ 1797–1801 ▲ 1801–1809 ▲ ▲ 1790 1797 1804 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1793 1794 1805 • Louis XVI guillotined • Polish rebellion • British navy wins during French suppressed by Battle of Trafalgar Revolution Russians 1800 • Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1 written 208 Painter and President by J.L.G. Ferris 1812 • United States declares 1807 1811 war on Britain • Embargo Act blocks • Battle of Tippecanoe American trade with fought against Tecumseh 1814 Britain and France and his confederacy • Hartford Convention meets HISTORY Madison • Treaty of Ghent signed ▲ 1809–1817 ▲ ▲ ▲ Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1811 1818 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 6 to 1808 preview chapter information. -

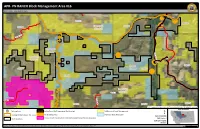

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page Ch ip C re e k 23N15E 23N17E 23N16E !j 23N14E Deer & Elk HD # 690 Rd ille cev Gra k Flat Cree Missouri River k Chouteau e e r C County P g n o D B r i d g e Deer & Elk R d HD # 471 UV236 !j Fergus 22N17E 22N14E County 22N16E 22N15E A Deer & Elk r ro w The Peak C HD # 426 r e e k E v Judi e th r Riv s e ge Rd r Ran o n R d 21N17E 21N15E 21N16E U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Services Agency Aerial Photography Field Office Area of Interest !j Parking Area Safety Zone (No Trespassing, No Hunting) US Bureau of Land Management º 1 6 Hunting Districts (Deer, Elk, Lion) No Shooting Area Montana State Trust Land 4 Date: 5/22/2020 2 Moline Ranch Conservation Easement (Seperate Permission Required) FWP Region 4 7 BMA Boundary 5 BLM 100K Map(s): 3 Winifred Possession of this map does not constitute legal access to private land enrolled in the BMA Program. This map may not depict current property ownership outside the BMA. It is every hunter's responsibility to know the 0 0.5 1 land ownership of the area he or she intends to hunt, the hunting regulations, and any land use restrictions that may apply. Check the FWP Hunt Planner for updates: http://fwp.mt.gov/gis/maps/huntPlanner/ Miles AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE– PN RANCH BMA # 16 Deer/Elk Hunting District: 426/471 Antelope Hunting District: 480/471 Hunting Access Dates: September 1 - January 1 GENERAL INFORMATION HOW TO GET THERE BMA Type Acres County Ownership » North on US-191 15.0 mi 2 20,203 Fergus Private » North on Winifred Highway 24.0 mi » West on Main St. -

Catalogue #19

Back of Beyond Books proudly releases Catalogue #19. We continue to feature books and ephemera from the American West but you’ll also find numerous pages of Americana, Travel and Photographic material along with Explora- tion, Mining and Native Americana. We’ve also picked up small collections of Poetry and Art Books which have been fun to catalogue. Perhaps my favorite genre of Catalogue #19 are the 21 Promotional items from western states and communities. These colorful pamphlets, mostly from the early 20th century, would make any Chamber of Commerce proud. It’s always interesting to see what items sell quickly in each catalogue. I of- ten guess wrong so I’ll leave the decisions up to you. Several items of note, however, include: The best association copy known of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian--inscribed to Edward Abbey, a beautifully bright advertising poster for the ‘Field Self Discharging Rake’, a scarce promotional for the Salt River Valley of Arizona, a full-plate tintype from Volcano, California, and six large format albumen photographs depicting archaeological sites of Arizona and New Mexico by John K. Hillers. I’m also taken with the striking and rare Broadside for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the very clean re- view copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the atlas from the Pike Expe- dition published in 1810. Thanks to my staff at the store for working around the piles and boxes of books. If you’re ever in Moab our shop is open daily; please stop in. Sophie Tomkiewicz used the skills she learned at the Colorado Rare Books School in developing Catalogue #19 and Eric Trenbeath is our designer. -

Low-Water Native Plants for Colorado Gardens: Prairie and Plains

Low-Water Native Plants for Colorado Gardens: Prairie and Plains Published by the Colorado Native Plant Society 1 Prairie and Plains Region Denver Botanic Gardens, Chatfield Photo by Irene Shonle Introduction This range map is approximate. Please be familiar with your area to know which This is one in a series of regional native planting guides that are a booklet is most appropriate for your landscape. collaboration of the Colorado Native Plant Society, CSU Extension, Front Range Wild Ones, the High Plains Environmental Center, Butterfly The Colorado native plant gardening guides cover these 5 regions: Pavilion and the Denver Botanic Gardens. Plains/Prairie Front Range/Foothills Many people have an interest in landscaping with native plants, Southeastern Colorado and the purpose of this booklet is to help people make the most Mountains above 7,500 feet successful choices. We have divided the state into 5 different regions Lower Elevation Western Slope that reflect different growing conditions and life zones. These are: the plains/prairie, Southeastern Colorado, the Front Range/foothills, the This publication was written by the Colorado Native Plant Society Gardening mountains above 7,500’, and lower elevation Western Slope. Find the Guide Committee: Committee Chair, Irene Shonle, Director, CSU Extension, area that most closely resembles your proposed garden site for the Gilpin County; Nick Daniel, Horticulturist, Denver Botanic Gardens; Deryn best gardening recommendations. Davidson, Horticulture Agent, CSU Extension, Boulder County; Susan Crick, Front Range Chapter, Wild Ones; Jim Tolstrup, Executive Director, High Plains Why Native? Environmental Center (HPEC); Jan Loechell Turner, Colorado Native Plant There are many benefits to using Colorado native plants for home Society (CoNPS); Amy Yarger, Director of Horticulture, Butterfly Pavilion. -

Riparian Restoration Summary

American Prairie Reserve & Prairie Stream Restoration Introduction to American Prairie Foundation American Prairie Foundation (APF) is spearheading a historic effort to reignite America’s passion for large-scale conservation by assembling the largest wildlife reserve of any kind in the lower 48 states. APF’s lands, called American Prairie Reserve (APR), are located on Montana’s Great Plains, just north of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Missouri River. Scientists have identified this place as an ideal location for the construction of a thriving prairie reserve capable of hosting an astonishing array of wildlife in an ecologically diverse environment. APF currently holds 123,346 acres of deeded and leased land. APF has three goals informing all activities on the Reserve: 1. Conservation: APF seeks to accumulate and manage enough private land that, when combined with existing public land, will create a fully functioning prairie-based wildlife reserve. When complete, the Reserve will consist of more than three million acres of private and public land (using the existing 1.1 million acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge as the public land anchor). With less than 1% of the world’s grasslands protected, the pristine condition of the land and abundance of indigenous species in the Northern Great Plains make the American Prairie Reserve region an ideal location for a conservation project of this scale. APF currently manages a conservation bison herd of approximately 140 animals—the first conservation bison herd in this part of Montana in more than 120 years. Collaborative research projects are also underway to assess existing populations of endemic species including pronghorn, prairie dogs, swift fox, long- billed curlews, and cougars. -

Federalists and Republicans 1789–1820

Federalists and Republicans 1789–1820 Why It Matters In the nation’s new constitutional government, important new institutions included the cabinet, a system of federal courts, and a national bank. Political parties gradually developed from the different views of citizens in the Northeast, South, and West. The new government faced special challenges in foreign affairs, including the War of 1812 with Great Britain. After the war, a spirit of nationalism took hold in American society. A new national bank was chartered, and Supreme Court decisions strengthened the power of the federal government. The Impact Today Policies and attitudes that developed at this time have helped shape the nation. • Important precedents were set for the relations between the federal and state governments. • Washington’s caution against foreign involvement has powerfully influenced American foreign policy. • Many Americans have a strong sense of national loyalty. The American Republic Since 1877 Video The Chapter 4 video, “The Battle of New Orleans,” chronicles the events of this pivotal battle of the War of 1812. 1798 • Alien and Sedition 1789 Acts introduced 1794 1804 • Washington elected • Jay’s Treaty • Lewis and Clark president signed explore and map Louisiana Territory L Washington J. Adams Jefferson 1789–1797 L 1797–1801 L 1801–1809 L 178519## 1795 1805 M M M M 1793 1799 1805 • Louis XVI guillotined 1794 • Beethoven writes • British navy during French • Polish rebellion Symphony no. 1 wins Battle of Revolution suppressed by Russians Trafalgar 150 Painter and President by J.L.G. Ferris 1808 • Congress bans 1812 international slave • United States declares trade war on Great Britain 1823 1811 • Monroe Doctrine 1819 declared • Battle of Tippecanoe • Spain cedes Florida fought against Tecumseh’s to the United States; Shawnee confederacy Supreme Court HISTORY decides McCulloch v. -

A Montanan Circle of Life Larkspur, Cattle and Grizzlies in the Gravelly Mountain Range Contribute to Trail Closures

THE LOCAL NEWS OF THE MADISON VALLEY, RUBY VALLEY AND SURROUNDING AREAS Montana’s Oldest Publishing Weekly Newspaper. Established 1873 75¢ | Volume 147, Issue 39 Thursday, September 5, 2019 A Montanan Circle of Life Larkspur, cattle and grizzlies in the Gravelly Mountain Range contribute to trail closures BY HANNAH KEARSE lanky, leafless stems from [email protected] palmate-leafed patches that huddle close to the ground. The smell of rotting cattle Blue-violet flowers, with dash- carcasses is attracting grizzly es of white, cluster the tops bears in the southern Gravelly of the flowering stem in the Range. The Madison Ranger summer months. The peren- District announced a tempo- nial can survive 60 to 70 years rary closure of two trails Aug. and has been a part of Mon- 28 due to the heightened risk tana’s landscape much longer of grizzly bear encounters. than cattle. Eight cows grazing on pub- Tall larkspur contains up to lic land died after consuming 20 different alkaloids, which too much larkspur, a native vary in toxicity. Poisonous poisonous plant. The Mon- content is highest during the tana Fish, Wildlife and Parks early stages of its growth. estimated that the reeking Toxicity levels can vary from meat has allured as many as patch to patch, and year to 20 grizzly bears to the area. To year in a single patch. minimize risk to recreation- According to U.S. Depart- ists, bird hunters and bow ment of Agriculture Poisonous hunters, Forest Service trails Plant Research, cattle con- 6405 and 6422 and access into sumption of larkspur usually the Teepee and Lobo Mesa peaks in late summer, when areas have been temporarily toxicity levels are declining. -

Pollution Prevention Appendix Appendix G: Pollution Prevention

Appendix O-O State of New Mexico Pollution Prevention Appendix Appendix G: Pollution Prevention Renewable Energy Resources Renewable energy sources, including solar, wind, hydropower, biomass, and geothermal, currently provide less than 1% (or 5.6 trillion BTUs) of New Mexico’s annual energy needs. The contribution of renewable energy has dropped from 6.6 trillion BTUs reported in 1997. This is contrary to the fact that our renewable energy resource base is very large and diverse. Table 6 provides a breakdown of consumption, by sector, for renewable energy in New Mexico. Table 6. Renewable Energy Consumption in New Mexico, 1999* Sector Energy Source Million KWH Consumed Residential Solar 147 Wood 996 Commercial Geothermal 29 Wood 147 Industrial Geothermal, Wind, and Solar 176 Wood and Waste 147 Total 1,642 4. Source: DOE/EIA State Energy Data Report 1999, printed May 2001. 5. *most current data available Table 7. Renewable Energy Production by Resource, 1999* Resource KWH Value ($ Millions) Fuel Wood 1,026 Million 6.5 (Note 1) Alcohol Fuels 346 Million 23.3 (Note 2) Hydroelectric 230 Million 15.2 (Note 3) Geothermal 119 Million 1.4 (Note 4) Wind 1.7 Million 0.119 (Note 5) Total 1,772.7 Million 46.51 Notes: *most current data available 1. DOE/EIA Energy Price and Expenditure Report, 1999. 2. Data from High Plains Ethanol Plant, Portales, NM; 15 million gal/yr @ $1.559 per gallon. 3. Edison Electric Institute, Yearbook 2000; value based on average NM electricity cost of $0.0663/kWh. 4. Southwest Technology Development Institute, NMSU; average NM natural gas cost of $3.62/million BTU. -

Gettysburg Historical Journal 2013

Volume 12 Article 8 2013 Gettysburg Historical Journal 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. (2013) "Gettysburg Historical Journal 2013," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 12 , Article 8. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol12/iss1/8 This open access complete issue is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gettysburg Historical Journal 2013 This complete issue is available in The Gettysburg Historical Journal: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol12/iss1/8 The Gettysburg Historical Journal Volume XII Fall 2013 History Department Gettysburg College Gettysburg, PA 17325 CONTENTS 7 Andrew Ewing Navigating Boundaries: The Development of Lewis, Clark and Pike 44 Rebekah Oakes "To Think of the Subject Unmans Me": An Exploration of Grief and Soldiering Through the Letters of Henry Livermore Abbott 68 Josh Poorman Escaping in the 'Tender, Blue Haze of Evening": The Morro Castle and Cruising as a Form of Leisure in 1930's America 89 Gabriella Hornbeck "La Bretagne aux Bretons?":Cultural Revival and Redefinitionof Brittany in Post-1945 France 97 David Wemer Europe's Little Tiger?: Reassessing Economic Transition in Slovakia under the Mečiar Government EDITORS Kaitlin Reed '13 is a senior History major and Spanish minor from Lancaster, Pennsylvania. She is interested in teaching English as a second language or continuing her studies at a higher level after her career at Gettysburg College. -

The Water Under Colorado's Eastern Plains Is

NEWS ENVIRONMENT The water under Colorado’s Eastern Plains is running dry as farmers keep irrigating “great American desert” Farmers say they’re trying to wean from groundwater, but admit there are no easy answers amid pressures of corn prices, urban growth and interstate water agreements By BRUCE FINLEY | [email protected] | The Denver Post PUBLISHED: October 8, 2017 at 6:00 am | UPDATED: October 9, 2017 at 8:19 am WRAY — Colorado farmers who defed nature’s limits and nourished a pastoral paradise by irrigating drought-prone prairie are pushing ahead in the face of worsening environmental fallout: Overpumping of groundwater has drained the High Plains Aquifer to the point that streams are drying up at the rate of 6 miles a year. The drawdown has become so severe that highly resilient fsh are disappearing, evidence of ecological collapse. A Denver Post analysis of federal data shows the aquifer shrank twice as fast over the past six years compared with the previous 60. While the drying out of America’s agricultural bread basket ($35 billion in crops a year) ultimately may pinch people in cities, it is hitting rural areas hardest. “Now I never know, from one minute to the next, when I turn on a faucet or hydrant, whether there will be water or not. The aquifer is being depleted,” said Lois Scott, 75, who lives west of Cope, north of the frequently bone-dry bed of the Arikaree River. A 40-foot well her grandfather dug by hand in 1914 gave water until recently, she said, lamenting the loss of lawns where children once frolicked and green pastures for cows. -

The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Final Draft Elizabeth Michell July 31 2009 An abbreviated version intended as guide for visitors OYL/iJ INTRODUCTION On late spring day visitor stands on slight rise on the banks of Big Sandy Creek from where across Cheyenne chief Black Kettles village once stood whole lot of he nothing comments laconically It is quiet place its peacefulness giving it timeless But quality the visitor is wrong and the timelessness is deceptive You can never visit the past again The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is in southeastern fifteen Colorado about miles northeast of the small town of Eads This is high plains country dusty and flat the drab greens of grass and scrub melding into the relentless browns of desiccated vegetation sand and soil The surrounding landscape is crisscrossed dirt by trails and fence lines dotted with windmills outbuildings and stock watering tanks At the site groves of cottonwoods tower along the gently sloping banks of Big Sandy Creek in fact it would be difficult to follow the stream course without the line of trees For most of the year water does not flow and the creek bed is choked with sand sagebrushes and other the site dry prairie species Though is part of shortgrass most of the land is prairie actually sandy bottomland that may eventually become It in Black Kettles tallgrass prairie was dry time and it is still dry evident by how much more sagebrush species there are now