Montana Natural Resource Coalition P.O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE SEES RECORD VISITATION for 2020 Lodging Reservation System Now Open for 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 1, 2021 Contact: Beth Saboe Senior Media and Government Relations Manager Phone: 406-600-4906 Email: [email protected] AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE SEES RECORD VISITATION FOR 2020 Lodging reservation system now open for 2021 American Prairie Reserve experienced a surge of visitation in 2020, recording more people staying overnight at its facilities than any previous year. Overnight reservations last year were up nearly 200 percent compared to 2019. The uptick in visitation was driven in part by people seeking respite outdoors from the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, and came despite having only 40 percent of the Reserve’s camping and lodging inventory available due to COVID-19 precautions. According to American Prairie’s Director of Recreation and Public Access Mike Kautz, 665 reservations were recorded in 2020 from the Reserve’s three huts, and two campgrounds. In comparison, there were 232 reservations recorded in 2019. A reservation is defined as a group reserving one unit of lodging (campsite, hut or cabin), and not a count of individual visitors. Kautz says each reservation had an average group size of 4 people. In addition, the majority of people visiting the Reserve are Montanans. In 2020, more than 88% of the reservations for American Prairie’s hut system and more than 50% of reservations for the campgrounds came from state residents. Kautz says this growing interest suggests visitors should consider making reservations earlier this year. “Word of this pretty unique prairie experience we offer is quickly spreading,” said Kautz. “We fully expect our reservation inventory to fill up quickly this year so anyone who is curious about the lodging options shouldn’t wait too long.” Reservations for American Prairie’s 2021 visitation season are now being accepted, as of February 1. -

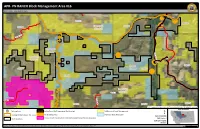

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page Ch ip C re e k 23N15E 23N17E 23N16E !j 23N14E Deer & Elk HD # 690 Rd ille cev Gra k Flat Cree Missouri River k Chouteau e e r C County P g n o D B r i d g e Deer & Elk R d HD # 471 UV236 !j Fergus 22N17E 22N14E County 22N16E 22N15E A Deer & Elk r ro w The Peak C HD # 426 r e e k E v Judi e th r Riv s e ge Rd r Ran o n R d 21N17E 21N15E 21N16E U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Services Agency Aerial Photography Field Office Area of Interest !j Parking Area Safety Zone (No Trespassing, No Hunting) US Bureau of Land Management º 1 6 Hunting Districts (Deer, Elk, Lion) No Shooting Area Montana State Trust Land 4 Date: 5/22/2020 2 Moline Ranch Conservation Easement (Seperate Permission Required) FWP Region 4 7 BMA Boundary 5 BLM 100K Map(s): 3 Winifred Possession of this map does not constitute legal access to private land enrolled in the BMA Program. This map may not depict current property ownership outside the BMA. It is every hunter's responsibility to know the 0 0.5 1 land ownership of the area he or she intends to hunt, the hunting regulations, and any land use restrictions that may apply. Check the FWP Hunt Planner for updates: http://fwp.mt.gov/gis/maps/huntPlanner/ Miles AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE– PN RANCH BMA # 16 Deer/Elk Hunting District: 426/471 Antelope Hunting District: 480/471 Hunting Access Dates: September 1 - January 1 GENERAL INFORMATION HOW TO GET THERE BMA Type Acres County Ownership » North on US-191 15.0 mi 2 20,203 Fergus Private » North on Winifred Highway 24.0 mi » West on Main St. -

Riparian Restoration Summary

American Prairie Reserve & Prairie Stream Restoration Introduction to American Prairie Foundation American Prairie Foundation (APF) is spearheading a historic effort to reignite America’s passion for large-scale conservation by assembling the largest wildlife reserve of any kind in the lower 48 states. APF’s lands, called American Prairie Reserve (APR), are located on Montana’s Great Plains, just north of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Missouri River. Scientists have identified this place as an ideal location for the construction of a thriving prairie reserve capable of hosting an astonishing array of wildlife in an ecologically diverse environment. APF currently holds 123,346 acres of deeded and leased land. APF has three goals informing all activities on the Reserve: 1. Conservation: APF seeks to accumulate and manage enough private land that, when combined with existing public land, will create a fully functioning prairie-based wildlife reserve. When complete, the Reserve will consist of more than three million acres of private and public land (using the existing 1.1 million acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge as the public land anchor). With less than 1% of the world’s grasslands protected, the pristine condition of the land and abundance of indigenous species in the Northern Great Plains make the American Prairie Reserve region an ideal location for a conservation project of this scale. APF currently manages a conservation bison herd of approximately 140 animals—the first conservation bison herd in this part of Montana in more than 120 years. Collaborative research projects are also underway to assess existing populations of endemic species including pronghorn, prairie dogs, swift fox, long- billed curlews, and cougars. -

A Montanan Circle of Life Larkspur, Cattle and Grizzlies in the Gravelly Mountain Range Contribute to Trail Closures

THE LOCAL NEWS OF THE MADISON VALLEY, RUBY VALLEY AND SURROUNDING AREAS Montana’s Oldest Publishing Weekly Newspaper. Established 1873 75¢ | Volume 147, Issue 39 Thursday, September 5, 2019 A Montanan Circle of Life Larkspur, cattle and grizzlies in the Gravelly Mountain Range contribute to trail closures BY HANNAH KEARSE lanky, leafless stems from [email protected] palmate-leafed patches that huddle close to the ground. The smell of rotting cattle Blue-violet flowers, with dash- carcasses is attracting grizzly es of white, cluster the tops bears in the southern Gravelly of the flowering stem in the Range. The Madison Ranger summer months. The peren- District announced a tempo- nial can survive 60 to 70 years rary closure of two trails Aug. and has been a part of Mon- 28 due to the heightened risk tana’s landscape much longer of grizzly bear encounters. than cattle. Eight cows grazing on pub- Tall larkspur contains up to lic land died after consuming 20 different alkaloids, which too much larkspur, a native vary in toxicity. Poisonous poisonous plant. The Mon- content is highest during the tana Fish, Wildlife and Parks early stages of its growth. estimated that the reeking Toxicity levels can vary from meat has allured as many as patch to patch, and year to 20 grizzly bears to the area. To year in a single patch. minimize risk to recreation- According to U.S. Depart- ists, bird hunters and bow ment of Agriculture Poisonous hunters, Forest Service trails Plant Research, cattle con- 6405 and 6422 and access into sumption of larkspur usually the Teepee and Lobo Mesa peaks in late summer, when areas have been temporarily toxicity levels are declining. -

American Prairie Bison Report

AMERICANBison PRAIRIE RESERVE Report 2015 10 Celebrating 10 Years of Bison Restoration American Prairie Reserve | 2015 Bison Report Introduction We are pleased to provide you with our annual American Prairie Reserve Bison Report. This year marks the 10th anniversary of bison restoration on the Reserve. We have come a long way since the first 16 bison stepped out of the trailer. The last decade has been a stunning success: • The bison herd in 2005 occupied just 80 acres of private land. Today, the bison graze 31,000 acres managed by multiple land management agencies. • The bison soon will be expanding onto another 22,000 acres. • We have combined the genetics of 2 source herds to gain genetic diversity. • We have exceeded the minimum population threshold for the conservation of founding genetic diversity. The next 10 years will bring more exciting milestones, and the future looks very bright as we continue our work to preserve this iconic species. Damien Austin Dr. Kyran Kunkel Reserve Supervisor Lead Scientist © APR © Susan Jorgenson 1 | American Prairie Reserve American Prairie Reserve | 2015 Bison Report Rationale Bison are ecologically extinct in North America. They have been petitioned to list as endangered and are classified by the IUCN as near-threatened globally. While a few conservation herds exist, none is large or has the potential to grow substantially and no new large herds are being created. As such, American Prairie Reserve set out to address this important conservation problem and use bison as a flagship species for our grassland restoration project. We aim to create the most significant conservation herd in North America as part of our efforts to recreate a fully-functional prairie ecosystem. -

2017 Wings Reg. Brochure

program 17 layout:Layout 1 2/22/17 2:10 PM Page 1 18th ANNUAL MONTANA AUDUBON BIRD FESTIVAL June 9–11, 2017 Best Western Plus Heritage Inn Great Falls, Montana John Lambing Russell Hill program 17 layout:Layout 1 2/22/17 2:10 PM Page 2 welcome Festival headquarters and lodging The Best Western Plus Heritage Inn is located off the 10th Avenue South We will be celebrating the milestone of Montana (I-15) exit in Great Falls and is within minutes of the CM Russell Museum, Audubon’s first 40 Years at our 18th Annual Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, Giant Springs State Park, First People’s Wings Across the Big Sky Festival, co-hosted by Buffalo Jump, Great Falls International Airport, Holiday Village Mall, and the the Upper Missouri Breaks Audubon Chapter. Rivers Edge Trail along the Missouri River. As the largest full-service hotel in This is shaping up to be a spectacular event and Central Montana with 231 guest rooms and over 17,000 sq. ft. event space we hope you will join us in Great Falls, June 9–11, with 12 meeting rooms, we are able to accommodate groups of all sizes. 2017. Registration will open at 1:00 p.m. so plan Complimentary features include: airport and area-wide transportation, to sign in and enjoy a special presentation parking, wireless internet, indoor pool and fitness center. The address is Friday afternoon, followed by a Barbecue and 1700 Fox Farm Road and is easily accessible from the south, north or west Celebration Friday evening. -

Beth Saboe Senior Public Relations Manager Phone: 406-600-4906 Email: [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAY 27, 2021 Contact: Beth Saboe Senior Public Relations Manager Phone: 406-600-4906 Email: [email protected] AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE GROWS BY 800 ACRES Montana nonprofit purchases Cow Creek property in Blaine County American Prairie Reserve is pleased to announce the purchase of 800 acres near Cow Creek, located in Blaine County and within the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. This parcel is American Prairie’s 32nd land acquisition and brings the conservation organization’s total deeded and leased acres to 420,425. Named for Cow Creek, which runs its length, the property lies just four miles north of the Missouri River. It is adjacent to existing American Prairie land and the secluded, rugged location inside the National Monument offers plentiful grazing for wildlife and attracts elk, deer, and big horn sheep. “Properties like Cow Creek connect existing public lands and provide crucial habitat, helping us to create a contiguous landscape where wildlife can thrive,” said Alison Fox, CEO of American Prairie Reserve. The parcel is three miles long, half a mile wide, and falls within the Cow Creek Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) and the Cow Creek Wilderness Study Area (WSA). The Cow Creek ACEC and Cow Creek WSA are both managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for the areas’ important historical and cultural values in addition to providing critical fish and wildlife habitat and opportunities for recreation. This new property also holds historical significance. The Nez Perce tribe crossed this region during the Flight of 1877 and followed Cow Creek as they fled the U.S. -

Summer Field Trip Guide 2018

Kelseya uniflora, ill. by Bonnie Heidel Summer Field Trip Guide 2018 MONTANA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY “...to preserve, conserve and study Montana’s native plants & plant communities.” mtnativeplants.org MNPS Field Trip Guidelines Enjoy a wide variety of fabulous Montana field trips this summer with the Montana Native Plant Society. Led by professional ecologists, botanists and natural scientists, these trips offer enriching and fun opportunities to get out and explore Montana’s abundant beauty. This guide is arranged by date so you can coordinate your summer Montana travel with an outing near your destination. You might even want to target a destination. Always call the listed trip leader for the most current information. This guide, prepared in early spring, cannot anticipate the many changes that may occur throughout the summer due to weather, fires or other unforeseen events. The trips vary from easy to difficult. Please read each description and contact the trip leader with your questions to insure the trip meets your expectations, physical abilities and circumstances. Please leave dogs and firearms at home in fairness to other participants and wildlife. Some field trips have size limits. If the leader requests that you call to reserve a spot, call again if you must cancel. Some trips are more child-friendly than others. Check with your trip leader. Be prepared for Montana’s instantaneous weather changes. Wear appropriate clothes and shoes. Bring food, water, extra clothes, rain gear, sunscreen, insect repellent, sunglasses, hat and any other personal gear you might need. You also may want to bring your favorite field guides and a notebook for recording species you see. -

20Th Annual Montana Audubon Bird Festival

20 TH ANNUAL MONTANA AUDUBON BIRD FESTIVAL June 7 –9, 201 9 Cottonwood Inn Glasgow, Montana a k n i t r a M b o B g n i b m a L n h o J Sunrise over Fort Peck Lake Above: Sage Thrasher welcome keynote speaker Montana Audubon is excited to host our 20th annual Wings Across the Big Sky bird Sean Gerrity festival in the stunning glaciated plains region of northeastern Montana! The Wonder of Birds in the American Prairie Reserve Region What makes the northern mixed grass prairie and glaciated plains so rich, This year’s festival home base will be the intriguing and important in regards to its birdlife? How might we protect it in Cottonwood Inn, in Glasgow, Montana, order to maximize its value and habitat suitability to the wide array of bird June 7 –9. Registration will open at 3 p.m. species that frequent this unique yet shrinking landscape? on Friday afternoon and is followed by a dinner buffet and our festival keynote Sean Gerrity, American Prairie Reserve Founder & Managing address that evening. Director and National Geographic Explorer, is committed to wildlife conservation and creating the largest Native prairie habitats in the area wildlife complex ever assembled in the continental support many important and United States. Mr. Gerrity and his team are dedicated uncommon grassland bird species. to building the Reserve for the benefit of Numerous field trips will explore humanity – from Native American and other local wildlife-rich landscapes of this unique communities neighboring the Reserve to the global and underappreciated region of visitors who enjoy the Reserve’s growing educational Montana. -

American Prairie Reserve Livestock Grazing Permit Change in Use

US Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management North Central Montana District American Prairie Reserve Change in Use Application SUMMARY OF INPUT RECEIVED DURING PUBLIC SCOPING December 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................... 1-1 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE PUBLIC SCOPING PERIOD ......................................................... 2-1 2.1 Public Scoping Period and Public Outreach ........................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Methods of Comment Collection ............................................................................................. 2-1 2.3 Public Meetings .............................................................................................................................. 2-2 3. SUMMARY OF PUBLIC INPUT ......................................................................................... 3-1 3.1 Summary of Public Input ............................................................................................................. 3-1 3.2 Issue Statements ........................................................................................................................... 3-2 3.3 Next Steps ...................................................................................................................................... 3-4 December 2018 American Prairie Reserve Change in Use Application i Summary of Input Received During Public Scoping ACRONYMS -

China Protected Areas Leadership Alliance Project

China Protected Areas Leadership Alliance Project Strengthening Leadership Capacity for Effective Management of China’s Protected Areas YEAR II A partnership of the China State Forestry Administration The Nature Conservancy China Program East-West Center 4-31 May 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………….…..…1 Map of China Model National Nature Reserves ………………………………………………………...…5 Descriptions of China’s 51 Model National Nature Reserves…………………………………..….………6 Training Needs for Protected Area Managers……………………………………………………….…….19 Year II Participants……………….……………………………………………………………….……….21 Participant Contact Information………………………………………………..…………….…….……...29 Classroom Training Schedule, Beijing Forestry University ….……………………………………...……31 Overview of Field Study and Collaborative Learning Component………......……………….…….…..…33 U.S. Field Study Agenda………………………………………………………………………...….……..36 U.S. Field Study Organizations…………………………………………………………….………..…….52 U.S. Field Study Speakers…………………………...……………………………………………….……60 U.S. Field Study Speaker Contact Information……………………………………………………………74 Project Staff ……………………………………….……………………………………………………....80 Project Staff Contact Information………………………………………………………………………....83 China Protected Areas Leadership Alliance Project Strengthening Leadership Capacity for Effective Management of China’s Protected Areas Executive Summary Protection of the natural and cultural heritage of China depends on the effective management of the nation’s protected areas. The Government of China has set aside fifteen -

American Prairie Coloring Book

ANIMALS OF THE PRAIRIE AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE American Prairie Reserve is creating a large prairie reserve in Montana to protect the many different kinds of plants and animals that live there. In this coloring book, you will learn about some of the animals that live on the Reserve. You can visit American Prairie Reserve with your family and see some of these animals! americanprairie.org (hargreavesphotography.com) Cover: Photo © Diane Hargreaves Front PRONGHORN ANTELOPE The pronghorn can run up to sixty-one miles per hour, and will travel as far as three hundred miles during its seasonal migration. ERRUGINOUS HAWKFerruginous hawks are usually rust colored, and the female can be one- and-a-half times larger than the male. The prairie dog got its name from the sound of its unique warning call, which reminded early settlers of a dog’s bark. Burrowing owls build their nests in holes dug in the ground by other animals, such as prairie dogs. They often look like they have “eyebrows,” making it easier to recognize them in the wild. The swift fox is known for its speed. It can run up to forty miles an hour and is one of the smallest foxes in the world. The long-billed curlew uses its long beak to find food hidden in the mud or in shallow water. The greater sage grouse is the largest type of grouse in North America. It has long, “spiky” tail feathers. Bison are the heaviest land animal in North America. They can weigh up to two thousand pounds. P.O.