190214 Efford RTSA Presentation Notes & Attachments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regiotram Kassel Betrieben Wird Die Regiontram in Kassel Durch Ein

erhöht deutlich die Lebensqualität der Be- 1960er Jahren, als die Albtalbahn bereits wohner. Probleme in der Innenstadt ist die kaum genutzte Güterstrecken der DB für den größere Breite der RT-Wagen, so dass diese Personenverkehr nutzte. Nachdem sich in der nicht auf allen Straßenbahnstrecken fahren 1990ern innerhalb weniger Wochen nach können. Einführung die Fahrgastzahlen verfünffacht hatten, war auch kein politischer Widerstand Stadtbahn Karlsruhe – Karlsruher Modell mehr zu erwarten. Auch heute wird das über Das Karlsruher Modell gilt als die Mutter der 400 km lange Streckennetz noch erweitert Stadt-Regionalbahnsysteme. Betrieben wird und ausgebaut. RegioTram Kassel es durch eine Kooperation zwischen der Alb- Betrieben wird die RegionTram in Kassel tal-Verkehrs-Gesellschaft (AVG), den Ver- City Bahn Chemnitz durch ein Joint Venture aus der Regionalbahn kehrsbetrieben Karlsruhe (VBK) sowie der Kassel (RBK) und der DB Region Nord. Als Deutschen Bahn (DB) Die Fahrzeuge sind Fahrzeuge kommen Alstom RegioCitadis zum Großteil noch aus den 1980er und Wagen zum Einsatz, von denen sich die Lan- 1990er Jahren der Firma DUEWAG, heute deshauptstadt Kiel zu Testzwecken im Juni Siemens Transportation Systems, die teilwei- 2007 einige ausgeliehen hatte. Es handelt se einzeln angepasst wurden. sich um Zweisystemfahrzeuge, die teilweise mit Dieselaggregat ausgestattet sind. Der Betrieb wurde 2007 aufgenommen, wobei der Vorlaufbetrieb seit Juni 2001stattfand. Die Fahrzeuge sind nach Figuren der Grimm- Quelle: City-Bahn Chemnitz GmbH schen Märchenwelt, die in engem Zusam- Im Chemnitz ist die Umspurung der Straßen- menhang mit Kassel stehen, benannt. Das bahn auf Normalspur bereits in den 1960ern Netz ist 184 km lang. Die an das RegioTram- geschehen, als die Stadt noch Karl-Marx- Netz angebundenen Städte und Gemeinden Stadt hieß. -

2 ) * CAD Courtesy Shuttle

Warm Welcome to Hong Kong CAD! CAD Courtesy shuttle bus (28 NOV 14) Schedule Useful information Departing Departing Arriving Tung Chung Regal Airport CAD HQ MTR Station Hotel • Wi-Fi in CAD HQ [SSID: CAD-Guest] Morning 08:25 08:40 08:50 - No username or password required Arriving Arriving Departing • In case of fire , please follow the instructions of Regal Airport Tung Chung CAD HQ our staff to the assembly point Hotel MTR Station • No smoking inside the building 15:45 15:55 16:10 Afternoon Delegates please note that the shuttle bus will depart punctually according to this schedule Public Transport to & from CAD HQ For Taxi drivers Tung Chung MTR Station CAD HQ 請送我到 For Public bus Route no. S1 ( Fare: HK$3.5) • Leave via Exit B and walk straight ahead to the 民航處總部大樓 undercover bus terminus to board the bus 香港國際機場東輝路111號1號 CAD HQ Tung Chung MTR Station / Airport For Public bus Route no. S1 ( Fare: HK$3.5) (((港龍大厦附近(港龍大厦附近))) • Leave via the side door of the CAD building (See map overleaf) and cross the road for the bus stop Please take me to the • Buses bound for Tung Chung MTR Station and Airport (Passenger Terminal Building) share the same stop Civil Aviation Department Headquarters Please check the direction of bus before boarding 1, Tung Fai Rd, For Taxi : • To call a taxi from CAD HQ, you may contact the Hong Kong International Airport reception desk for assistance (Near Dragonair House) Public Bus No. S1 (Undercover bus terminus) ` Exit D Exit B CAD Courtesy Exit A Shuttle bus Urban Taxi [HLAACP] Stand Map in the vicinity of Tung Chung MTR Customer Service Centre where an on-loan Octopus can be obtained Station. -

Wellington Town Belt Management Plan – June 2013 49

6 Recreation The play area at Central Park, Brooklyn. A flying fox and bike skills area are also provided. Guiding principles The Town Belt is for all to enjoy. This concerns equity of access and use of the Town Belt. The Council believes that the Town Belt should be available for all Wellingtonians to enjoy. The Council is committed to ensuring that the Town Belt will continue to be improved with more access and improved accessibly features where it is reasonably practicable to do so. The Town Belt will be used for a wide range of recreation activities. The Town Belt should cater for a wide range of sporting and recreation activities managed in a way to minimise conflict between different users. Co-location and intensification of sports facilities within existing hubs and buildings is supported where appropriate. 6.1 Objectives 6.1.1 The Town Belt is accessed and used by the community for a wide range of sporting and recreational activities. 6.1.2 Recreational and sporting activities are environmentally, financially and socially sustainable. 6.1.3 Participation in sport and recreation is encouraged and supported. 6.1.4 The Town Belt makes a significant contribution to the quality of life, health and wellbeing of Wellingtonians by increasing a range of physical activity and providing active transport routes and access to natural environments 6.1.5 The track (open-space access) network provides for a range of user interests, skills, abilities and fitness levels, and pedestrian and cycling commuter links. 6.1.6 Management and development of formal sporting facilities and associated infrastructure does not compromise the landscape and ecological values of the Town Belt. -

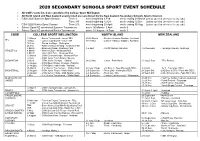

2020 Secondary Schools Sport Event Schedule

2020 SECONDARY SCHOOLS SPORT EVENT SCHEDULE All CSW events listed are sanctioned by College Sport Wellington All North Island and New Zealand events listed are sanctioned by the New Zealand Secondary Schools Sports Council. CSW 2020 Summer Sport Season: Term 1: week beginning 3 Feb week ending 29 March [unless specified otherwise for any code] Term 3/4: week beginning 12 Oct week ending 12 Dec [unless specified otherwise for any code] CSW 2020 Winter Sport Season: Term 2/3: week beginning 28 April week ending 30 Aug [unless specified otherwise for any code] School Sport NZ sanctioned Summer Tournament week: 30 March - 3 April week 9 School Sport NZ sanctioned Winter Tournament week: 31 August - 4 Sept week 7 CODE COLLEGE SPORT WELLINGTON NORTH ISLAND NEW ZEALAND 19 March - Senior Tournament - venue TBA 25-26 March - Seniors -Harbour Stadium, Auckland AFL 10 Nov - Junior Tournament - venue TBA 18-19 Nov - Juniors -Harbour Stadium, Auckland 16 Feb - Round the Bays - Wellington 25 Feb - AWD selection Meeting - Newtown Park 3 March - McEvedy Shield - Newtown Park 3-5 April - Porritt Stadium, Hamilton 4-6 December - Tauranga Domain, Tauranga ATHLETICS 4 March - Western Zone - Newtown Park 5 March - Hutt / Girls Zone - Newtown Park 12 March - CSW Championships - Newtown Park 23 July - CSW Junior Team Finals - Naenae BADMINTON 29 July - CSW Junior Champs - Haitaitai 24-26 Nov - Junior - Palm North 31 Aug-3 Sept - TRA, Porirua 12 August - CSW Open Singles Champs - Haitaitai 21 August - CSW Open Team Finals - Haitaitai 26 March - 3 x 3 Senior -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Rail Network Investment Programme

RAIL NETWORK INVESTMENT PROGRAMME JUNE 2021 Cover: Renewing aged rail and turnouts is part of maintaining the network. This page: Upgrade work on the commuter networks is an important part of the investment programme. 2 | RAIL NETWORK INVESTMENT PROGRAMME CONTENTS 1. Foreword 4 2. Introduction and approval 5 • Rail Network Investment Programme at a glance 3. Strategic context 8 4. The national rail network today 12 5. Planning and prioritising investment 18 6. Investment – national freight and tourism network 24 7. Investment – Auckland and Wellington metro 40 8. Other investments 48 9. Delivering on this programme 50 10. Measuring success 52 11. Investment programme schedules 56 RAIL NETWORK INVESTMENT PROGRAMME | 3 1. FOREWORD KiwiRail is pleased to present this This new investment approach marks a turning point that is crucial to securing the future of rail and unlocking its inaugural Rail Network Investment full potential. Programme. KiwiRail now has certainty about the projected role of rail Rail in New Zealand is on the cusp of in New Zealand’s future, and a commitment to provide an exciting new era. the funding needed to support that role. Rail has an increasingly important role to play in the This Rail Network Investment Programme (RNIP) sets out transport sector, helping commuters and products get the tranches of work to ensure the country has a reliable, where they need to go – in particular, linking workers resilient and safe rail network. with their workplaces in New Zealand’s biggest cities, and KiwiRail is excited about taking the next steps towards connecting the nation’s exporters to the world. -

Travel to the Edinburgh Bio Quarter

Travel to Edinburgh Bio Quarter Partners of the Edinburgh Bio Quarter: Produced by for Edinburgh Bio Quarter User Guide Welcome to the travel guide for the Edinburgh Bio Quarter! This is an interactive document which is intended to give you some help in identifying travel choices, journey times and comparative costs for all modes of travel. Please note than journey times, costs etc are generalised . There are many journey planning tools available online if you would like some more detail (links provided throughout document). - Home Button Example - Link to external information - Next page Example - Link to internal information For the Royal Infirmary Site Plan, please click here © OpenStreetMap contributors Please select your area of origin… Fife East Lothian West Edinburgh Lothian Midlothian Borders Please select which area of Edinburgh… West North West North East City Centre South East South West South Walking Distance and Time to EbQ Niddrie Prestonfield Craigmillar The Inch Shawfair Danderhall Journey Times Liberton 0 – 5 minutes Moredun 5 – 10 minutes 10 – 20 minutes EbQ Boundary Shawfair Railway Station For cycling Bus Stops For more information, please click here Bus Hub Cycling Distance and Time to EbQ Leith Edinburgh City Centre Portobello Murrayfield Musselburgh Brunstane Newington Newcraighall Morningside Shawfair Danderhall Swanston Journey Times 0 – 10 minutes Dalkeith 10 – 20 minutes 20 – 30 minutes Loanhead EbQ Bonnyrigg Closest Train Stations For Public Transport For more information on cycling to work, please click here -

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India Is an Important

Transport in India Transport in the Republic of India is an important part of the nation's economy. Since theeconomic liberalisation of the 1990s, development of infrastructure within the country has progressed at a rapid pace, and today there is a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air. However, the relatively low GDP of India has meant that access to these modes of transport has not been uniform. Motor vehicle penetration is low with only 13 million cars on thenation's roads.[1] In addition, only around 10% of Indian households own a motorcycle.[2] At the same time, the Automobile industry in India is rapidly growing with an annual production of over 2.6 million vehicles[3] and vehicle volume is expected to rise greatly in the future.[4] In the interim however, public transport still remains the primary mode of transport for most of the population, and India's public transport systems are among the most heavily utilised in the world.[5] India's rail network is the longest and fourth most heavily used system in the world transporting over 6 billionpassengers and over 350 million tons of freight annually.[5][6] Despite ongoing improvements in the sector, several aspects of the transport sector are still riddled with problems due to outdated infrastructure, lack of investment, corruption and a burgeoning population. The demand for transport infrastructure and services has been rising by around 10% a year[5] with the current infrastructure being unable to meet these growing demands. According to recent estimates by Goldman Sachs, India will need to spend $1.7 Trillion USD on infrastructure projects over the next decade to boost economic growth of which $500 Billion USD is budgeted to be spent during the eleventh Five-year plan. -

LOWER NORTH ISLAND LONGER-DISTANCE ROLLING STOCK BUSINESS CASE PREPARED for GREATER WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL 2 December 2019

LOWER NORTH ISLAND LONGER-DISTANCE ROLLING STOCK BUSINESS CASE PREPARED FOR GREATER WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL 2 December 2019 This document has been prepared for the benefit of Greater Wellington Regional Council. No liability is accepted by this company or any employee or sub-consultant of this company with respect to its use by any other person. This disclaimer shall apply notwithstanding that the report may be made available to other persons for an application for permission or approval to fulfil a legal requirement. QUALITY STATEMENT PROJECT MANAGER PROJECT TECHNICAL LEAD Doug Weir Doug Weir PREPARED BY Doug Weir, Andrew Liese CHECKED BY Jamie Whittaker, Doug Weir, Deepa Seares REVIEWED BY Jamie Whittaker, Phil Peet APPROVED FOR ISSUE BY Doug Weir WELLINGTON Level 13, 80 The Terrace, Wellington 6011 PO Box 13-052, Armagh, Christchurch 8141 TEL +64 4 381 6700 REVISION SCHEDULE Authorisation Rev Date Description No. Prepared Checked Reviewed Approved by by by by 1 27/07/18 First Draft Final DW, AL JW JW DW 2 24/10/18 Updated First Draft Final DW JW JW DW Revised Draft Final (GWRC 3 05/08/19 DW DW PP DW Sustainable Transport Committee) 3 20/08/19 Updated Revised Draft Final DW DS PP DW Amended Draft Final 4 26/09/19 DW DW PP DW (GWRC Council) 5 02/12/19 Final DW DW PP DW Stantec │ Lower North Island Longer-Distance Rolling Stock Business Case │ 2 December 2019 Status: Final │ Project No.: 310200204 │ Our ref: 310200204 191202 Lower North Island Longer-Distance Rolling Stock Busines Case - Final.docx Executive Summary Introduction This business case has been prepared by Stantec New Zealand and Greater Wellington Regional Council (GWRC), with input from key stakeholders including KiwiRail, Transdev, Horizons Regional Council and the NZ Transport Agency (NZTA), and economic peer review by Transport Futures Limited. -

Bay of Plenty Region Passenger and Freight Rail FINAL Report May 2019

1 | P a g e Bay of Plenty Passenger and Freight Rail Phase 1 Investigation Report May 2019 Contents Page Contents Page ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.0 Overall Findings and Future Opportunities ................................................................................. 6 2.1 Overall Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Future Opportunities ............................................................................................................ 10 3.0 Bay of Plenty Passenger and Freight Rail Investigation 2019 ................................................... 13 3.1 Phase 1 Investigation ............................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Stakeholders / Partners ........................................................................................................ 13 3.3 New Zealand Transport Agency Business Case Approach .................................................... 14 3.4 Bay of Plenty Rail Strategy 2007 ........................................................................................... 14 4.0 National Strategy and Policy Settings ...................................................................................... -

Saarbahn Mit Einsystemfahrzeugen Und Elektrifizierung Von Lücken

G. Stengel: Schienenverkehr 21.08.2018 Seite 1/4 Schienenverkehr in der Region: Saarbahn mit Einsystemfahrzeugen und Elektrifizierung von Lücken Inhalt Saarbahn mit Einsystemfahrzeugen 1 Saarbahn endet in Brebach 2 Saarbrücken Hbf - Saargemünd mit RB (15 KV) 2 RB bis Wadgassen 3 Saarbrücken - Illingen - Lebach 3 Saarbrücken - Zweibrücken 3 Streckenkombinationen 3 Nahestrecke elektrifizieren 3 Niedtalbahn elektrifizieren 3 Elektrifizierung von Bahnstrecken allgemein 4 Quellen 4 Zielsetzung 4 Saarbahn mit Einsystemfahrzeugen Das Konzept von Klimmt/Ried 2010, modifiziert und erweitert von Ried/Stengel 2014 beschäftigt sich mit der Erweiterung der bestehenden Saarbahnlinie (TramTrain, Stadtbahn). Nach Neuordnung der Gleise im Bereich der Achterbrücke wäre eine vom Fernverkehr getrennte TramTrain-Trasse möglich. Ferner könnten die vorhandenen Trassen links der Saar in einen kleinen Ring über Grossrosseln bis nach Forbach und einen großen Ring über Wadgassen - Überherrn einbezogen werden. Gewissermaßen ein Nebeneffekt dieser Überlegungen war die Erkenntnis, dass die bislang eingesetzten in Anschaffung und Betrieb teuren Zweisystemfahrzeuge nur für Teilstrecken benötigt werden. Die 15 KV- Bahnstromtechnik ist bei vielen Fahrten nur auf dem Abschnitt Römerkastell - Brebach und zukünftig, d.h. nach Elektrifizierung der Bahnstrecke bis Lebach, auf dem Abschnitt Lebach - Lebach-Jabach erforderlich. Nur für die Fahrten bis Hanweiler bzw. Saargemünd ist die Zweisystemtechnik auf einer längeren Strecke erforderlich. Um bei einem Großteil der Fahrten auch 750 V-Fahrzeuge einsetzen zu können, wurde in Ried/Stengel 2014 vorgeschlagen, die Linien an der Haltestelle Römerkastell enden zu lassen und von dort einen Zugang zur Werkstatt unter der Brücke durch über die Brebacher Landstraße zu bauen. Damit können auch Fördergelder für den Brückenbau gesichert werden. G. Stengel: Schienenverkehr 21.08.2018 Seite 2/4 Saarbahn endet in Brebach Einen Schritt weiter geht folgender Vorschlag: Das Durchgangsgleis 2 wird in Brebach komplett abgebaut. -

Sounder Commuter Rail (Seattle)

Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Final Report PRC 14-12 F Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Texas A&M Transportation Institute PRC 14-12 F December 2014 Authors Jolanda Prozzi Rydell Walthall Megan Kenney Jeff Warner Curtis Morgan Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 8 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 9 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 10 Sharing Rail Infrastructure ........................................................................................................ 10 Three Scenarios for Sharing Rail Infrastructure ................................................................... 10 Shared-Use Agreement Components .................................................................................... 12 Freight Railroad Company Perspectives ............................................................................... 12 Keys to Negotiating Successful Shared-Use Agreements .................................................... 13 Rail Infrastructure Relocation ................................................................................................... 15 Benefits of Infrastructure Relocation ...................................................................................