The Contribution of the Arts Association to Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday Matinée Study Guide

Zoellner Arts Center 420 East Packer Avenue Lehigh University Bethlehem, PA 2016-17 Season Monday Matinée Study Guide Alice in Wonderland Tout à Trac Monday, March 20, 2017 at 10 a.m. Baker Hall, Zoellner Arts Center, Lehigh University 420 E Packer Ave, Bethlehem, PA 18015 12/27/16 Study Guide: Tout à Trac Alice in Wonderland, page 1 Using This Study Guide On Monday, March 20 your class will attend a performance of Alice in Wonderland at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your class room prior to, as well as after the performance. These activities are designed to connect with disciplines in addition to arts including: Physical activities Communication (verbal and non-verbal) Leadership Architecture Trust building Physics Teamwork Physical Sciences Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: • Review with your students the Know Before You Go items on page 4. • Discuss with your students the information on pages 5-8: About the Story and About the Company. • Check out the definitions & explanations in Elements of Stagecraft on page 9. • Engage your class in two or more activities on pages 10-16. At the Performance • Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. • Encourage the students to remember what they know or learned about the story. -

The Church in Namibia: Political Handmaiden Or a Force for Justice and Unity? Christo Botha*

Journal of Namibian Studies, 20 (2016): 7 – 36 ISSN: 2197-5523 (online) The church in Namibia: political handmaiden or a force for justice and unity? Christo Botha* Abstract The role of churches in Namibia had investigated by researchers who aimed to docu- ment the history of various churches, as well as those who highlighted the role of black churches in particular, as mouthpieces for the disenfranchised majority in the struggle against apartheid. This article aims to shed light on a matter that had received relatively little attention, namely the church as an instrument of social justice and peace. An assessment of the role of various churches reveal to what extent these institutions were handicapped by ethnocentric concerns, which militated against the promotion of ecumenical cooperation. Except for a brief period in the 1970s and 1980s when the Council of Churches in Namibia served as an instrument for inter- church cooperation and promotion of social justice projects, little had arguably been achieved in establishing workable, enduring ecumenical ties. An attempt will be made to account for this state of affairs. Introduction Much is often made of the fact that Namibia is a largely Christian country, with about 90% of the population belonging to various Christian denominations. However, what strikes one when looking at the history of Christianity in the country and the role of the church, is the absence of evidence to support any claims that religion was a potent force for promoting the cause of human rights and mutual understanding and for eliminating ethnic divisions. In assessing the role of religion and the church in Namibian society, this article is concerned with three issues. -

25 October 1985

other prices on page 3 Manure 'bomb' and missing invitation THE EDITORIAL STAFF of The Namibian were not invited to at Apparently all the local press, with the exception of The Namibian, tend the Administrator General's annual 'garden party' on Wednes were in attendance, and a message was left at the gate to 'let us in' day, which - accordin2 to those present - was a lavish affair with if we chose to arrive. the Windhoek 'Who's Who' all there. Whether the invitation 'oversight' was an omission or deliberate, the fact is that it never arrived, and neither was there any explanation from Some of those who attended expressed surprise that The Namibian Mr Pienaar's office regarding the snub. had not been invited, but officials claimed it had not been a snub and A 'bomb scare' preceded the function, but the mysterious parcel that Mr Louis Pienaar was 'not one to bear grudges'. side the front gates of SW A House turned out to be manure. BY GWEN LISTER THE INTERIM GOVERNMENT Cabinet was deeply divided today after an eleventh hour settlement which will mean setting aside the appointment of Mr Pieter van der Byl as a Judge. The deal struck last night avoided a bitter and costly courtroom clash between Cabinet Ministers. And the settlement is a blow to the fincH throes of asettlement , but Finance Minister Mr Dirk Mudge there are loose ends to be tied up'. who supported the appointment of a South African Justice Depart Asked about the 'Constitution ment official as a Judge of the al Council', he said: 'We must now Supreme Court and Chairman of find a chairman' . -

L'identité Politique Et Culturelle Des Allemands De Namibie Face À L

L’identité politique et culturelle des Allemands de Namibie face à l’Indépendance Catherine Robert To cite this version: Catherine Robert. L’identité politique et culturelle des Allemands de Namibie face à l’Indépendance. Histoire. 1991. dumas-01297904 HAL Id: dumas-01297904 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01297904 Submitted on 5 Apr 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. treue tZiibloOt! 2 Remerciements je tiens a exprimer ma plus vive reconnaissance au C.R.E.D.U. de Nairobi. à M. K.Hess, directeur de la Deutsch - Namibische Vereinigung e.V. IFRA 610110111% 97°43°° W NAM P 3 Introduction. o Le 21 mars 19 -jour anniversaire du massacre de Sharpeville, banlieue noire du :Tr.nsvI en Afrique du Sud- la Namibie, derniere colonie en Afrique, si l'on excepte Melilla et Ceuta, accede a l'independance. Cette independance intervient apres la liberation, au debut de Palm& 1990, de Nelson Mandela, leader de l'A.N.C. et dans un contexte de détente internationale lie l'ebranlement des pays de l'Est. La transformation des rapports entre les deux blocs ayant des consequences directes sur la situation de l'Afrique australe, elle contribue a mettre un terme a trente ans de controverses et d'affrontements entre la Republique Sud-Africaine, ses voisins socialistes, l'O.N.U. -

Namibia Revolution

Namibia ~ s 1 Revolution 1 \ l ) ~ PUBLISHED BY : THE PERMANENT SECRETARIAT OF THE AFRO·ASIAN PEOPLES' SOLIDARITY ORGANIZATION 17 i:r. 1975 NAMIBIA REVOLUTION P ubli shed by : The Permanent Secretariat of THE AFRO-ASIAN PEOPLES' SOLIDARITY ORGANIZATION 89, Abdel Aziz Al Saoud St ., Maniai CAmO - U.A.R. Aeamifda · .9lettetluticm • AFRO-ASIAN I•UBLICATIONS (38) March 1971 CONTENTS Page Statement by the representative of SWAPO on the occasion of the Fourth Anniversary of the launching. of armed struggle in Namibia 7 Address of Mr. Youssef El Sebai, Secretary General of the A.A.P.S.O ., on the Day of Solidarity with the People of Namibia marking the anniver- sary of the beginning of the armed struggle . 15 SWAPO'S letter to the United Nations Secretary- .r General U THANT . 19 Security Council reference to World Court: a step backward . .• 29 The South African Government continues to underrate the terrorism and oppression it has let loose in Namibia 0 •• 0 • • •• •• • 0 • •••••• 0 ••••• • 35 The historical background - a long record of struggle . 37 South Africa's intentions 43 STATEMENT BY THE REPRESENTATIVE OF THE SOUTH WEST AFRICA PEOPL~'S ORGANIZATION (SWAPO) ON THE OCCASION OF THE FOURTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE LAU~HING OF ARMED STRUGGLE IN NAMIBIA (26 August 1970, Cairo, U.A.R.) Mr:., Chairman, Allow me to express my sincere gratitude to ali of you for accepting our invitation to joln us in the marking of this very important day in the history of the Namibian people's struggle for their national independance and freedom, in the struggle against South Africa's occupation of our Ncitional Territory. -

Fill in the Blank, Multiple Choice, Short Answer • Costume Design Usually Involves Researching, D

Costume/Set Design notes – fill in the blank, multiple choice, short answer Costume design usually involves researching, designing and building the actual items from conception. Four types of costumes are used in theatrical design, Historical, fantastic, dance, and modern. Designs are first sketched out and approved In its earliest form, costumes consisted of theatrical prop masks The leading characters will have more detail and design to make them stand out Scenic design (also known as stage design, set design or production design) is the creation of theatrical scenery. Scenic designers are responsible for creating scale models of the scenery, renderings, and paint elevations as part of their communication with other production staff. Theatrical scenery is that which is used as a setting for a theatrical production. Flats, short for Scenery Flats, are flat pieces of theatrical scenery which are painted and positioned on stage so as to give the appearance of buildings or other backgrounds. Soft covered flats (covered with canvas or muslin) A fly system is a system of lines, counterweights, pulleys Improv Notes – short answer Describe what shapes the action of an Improv scene? Audience suggestions or unknown topics List two things that make Improv different from traditional theatre? The elements of spontaneity, unpredictability and risk of not knowing if the scene will work out Why do you think there is no guarantee that an Improv scene will work? You never know what the suggestions or topics will be ahead of time List at least three ways that an actor defines the reality of the scene? Giving someone a name, identifying a relationship, identifying a location, using space object work to define the physical environment Describe what “Blocking” means. -

Broadway Dramatists, Hollywood Producers, and the Challenge of Conflicting Copyright Norms

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 16 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Winter 2014 Article 3 2014 Once More unto the Breach, Dear Friends: Broadway Dramatists, Hollywood Producers, and the Challenge of Conflicting Copyright Norms Carol M. Kaplan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Carol M. Kaplan, Once More unto the Breach, Dear Friends: Broadway Dramatists, Hollywood Producers, and the Challenge of Conflicting Copyright Norms, 16 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 297 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol16/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Once More unto the Breach, Dear Friends: Broadway Dramatists, Hollywood Producers, and the Challenge of Conflicting Copyright Norms Carol M. Kaplan* ABSTRACT In recent decades, studios that own film and television properties have developed business models that exploit the copyrights in those materials in every known market and in all currently conceivable forms of entertainment and merchandising. For the most part, uniform laws and parallel industry cultures permit smooth integration across formats. But theater is different. The work-made-for-hire provisions that allow corporations to function as the authors of the works they contract to create do not easily align with the culture and standard contract provisions of live theater. Conflicts arise when material that begins as a Hollywood property tries to make Carol M. -

Registratur PA.25 Hans Und Trudi Jenny Journalismus Und

Registratur PA.25 Hans und Trudi Jenny Journalismus und Studienreisen. Die Teilsammlung des Schweizer Ehepaars Hans und Trudi Jenny zum südlichen Afrika (1957–1995) Journalism and Study Travels. The Papers and Manuscripts of the Swiss Couple Hans and Trudi Jenny concerning Southern Africa (1957–1995) Zusammengestellt von / Compiled by Caro van Leeuwen Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Centre – Southern Africa Library 2016 REGISTRATUR PA.25 Registratur PA.25 Hans und Trudi Jenny Journalismus und Studienreisen. Die Teilsammlung des Schweizer Ehepaars Hans und Trudi Jenny zum südlichen Afrika (1957–1995) Journalism and Study Travels. The Papers and Manuscripts of the Swiss Couple Hans and Trudi Jenny concerning Southern Africa (1957–1995) Zusammengestellt von / Compiled by Caro van Leeuwen Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Centre – Southern Africa Library 2016 © 2016 Basler Afrika Bibliographien Herausgeber / Publisher Basler Afrika Bibliographien P.O. Box 2037 CH 4001 Basel Switzerland www.baslerafrika.ch Alle Rechte vorbehalten / All rights reserved Übersetzung / Translation: Caroline Jeannerat (Johannesburg) Gedruckt von / Printed by: Job Factory Basel AG ISBN 978-3-905758-75-7 Inhalt / Contents I Einleitung ix Hans Robert Jenny & Trudi Jenny-Leu x Zur Sammlung in den BAB xi Erschliessung xi Bedeutung des Teilnachlasses xiv Zum Findbuch xiv Introduction xv Hans Robert Jenny & Trudi Jenny-Leu xvi On the Jenny collection at the BAB xvii Cataloguing xvii Significance of the Jenny collection at the BAB xx On the finding aid xx II Registratur PA.25 / Inventory PA.25 1 Gruppe I Biografisches Schriftgut – Biographical Documents 1 Gruppe II Korrespondenz – Correspondence 21 Gruppe III Manuskripte – Manuscripts 62 Gruppe IV Publikationen – Published Articles 75 Gruppe VI Varia 85 Personenregister – Index of Names 102 Das Personenarchiv der Basler Afrika Bibliographien Die Basler Afrika Bibliographien (BAB) nehmen (Teil-)Nachlässe mit Bezug auf Namibia und das Südliche Afrika in ihr Archiv auf. -

A Sourcebook of Interdisciplinary Materials in American Drama: JK Paulding," the Lion of the West." Showcasing American Drama

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 236 723 CS 504 421 AUTHOR Jiji, Vera M., Ed. TITLE A Sourcebook of InterdisciplinaryMaterials in American Drama: J. K. Paulding, "TheLion of the West." Showcasing American Drama. INSTITUTION City Univ. of New York, Brooklyn, N.Y.Brooklyn Coll. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities(NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 28p.; Produced by the Program for Cultureat Play: Multimedia Studies in American Drama,Humanities Institute, Brooklyn College. Print is smalland may not reproduce well. Cover title: AHandbook of Source Materials on The Lion of the West by J. K. Paulding. AVAILABLE FROMMultimedia Studies in American Drama, Brooklyn College, Bedford Ave. and Ave. H,Brooklyn, NY 11210 ($2.00). PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Studies; *Drama; HigherEducation; Integrated Activities; InterdisciplinaryApproach; *Literary History; *Literature Appreciation;Research Skills; *Resource Materials; SecondaryEducation; *United States History; *United StatesLiterature IDENTIFIERS *Lion of the West (Drama); Paulding (JamesK) ABSTRACT Prepared as part of a project aimed atredressing the neglect of American drama in college andsecondary school programs in drama, American literature, and Americanstudies, this booklet provides primary and secondary sourcematerials to assist teachers and students in the study of James K.Paulding's nineteenth century comedy, "The Lion of the West." Thefirst part of the booklet contains (1) a discussion of the Yankeetheatre, plays written around a character embodyinguniquely American characteristics andfeaturing specialist American actors;(2) a review of the genesis of the play; (3) its production history;(4) plot summaries of its various versions; (5) its early reviews;(6) biographies of actors appearing in various productions; and (7) adiscussion of acting in period plays. -

New Actresses and Urban Publics in Early Republican Beijing Title

Carnegie Mellon University MARIANNA BROWN DIETRICH COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements Doctor of Philosophy For the Degree of New Actresses and Urban Publics in Early Republican Beijing Title Jiacheng Liu Presented by History Accepted by the Department of Donald S. Sutton August 1, 2015 Readers (Director of Dissertation) Date Andrea Goldman August 1, 2015 Date Paul Eiss August 1, 2015 Date Approved by the Committee on Graduate Degrees Richard Scheines August 1, 2015 Dean Date NEW ACTRESSES AND URBAN PUBLICS OF EARLY REPUBLICAN BEIJING by JIACHENG LIU, B.A., M. A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the College of the Marianna Brown Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Carnegie Mellon University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY August 1, 2015 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help from many teachers, colleages and friends. First of all, I am immensely grateful to my doctoral advisor, Prof. Donald S. Sutton, for his patience, understanding, and encouragement. Over the six years, the numerous conversations with Prof. Sutton have been an unfailing source of inspiration. His broad vision across disciplines, exacting scholarship, and attention to details has shaped this study and the way I think about history. Despite obstacle of time and space, Prof. Andrea S. Goldman at UCLA has generously offered advice and encouragement, and helped to hone my arguments and clarify my assumptions. During my six-month visit at UCLA, I was deeply affected by her passion for scholarship and devotion to students, which I aspire to emulate in my future career. -

Theatrical Insurance Supplemental Application

APPLICATION FOR: Theatrical Supplemental Application SECTION I. GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Contact Person: Contact Person Title: Phone No.: Fax No.: Email: 2. Name of proposed Insured (“Applicant”): Address: City, State, Zip: Website: SECTION II. REQUESTED INSURANCE LIMITS 1. GENERAL LIABILITY GENERAL AGGREGATE: $ PER OCCURRENCE: $ PERSONAL/ADVERTISING $ PRODUCTS/OPERATIONS $ FIRE DAMAGE: $ MEDICAL EXPENSE $ 2. EXCESS: AGGREGATE LIMIT: $ EACH OCCURRENCE LIMIT: $ SECTION III. DESCRIPTION OF RISK 1. Brief description of production and story line. Also indicate if Drama, Comedy or Musical. If Musical, with Dancing? 2. Describe any and all special stunts and/or acrobatics or hazardous activity and/or pyrotechnics or equipment: Theatrical Supplemental Application 022521 Page 1 of 3 aliverisk.com 3. Are Players: Employees of Production Company or Independent Contractors Nature of Stunt(s): Safety Precaution(s): 4. Name and Address of Theater: a. Is show touring? Yes No If yes, please attach schedule. IF TOURING, ATTACH COMPLETE ITENERARY INCLUDING TRAVEL DATE, NAME OF VENUE AND ESTIMATED ADMISSIONS OF APPLICABLE AND/OR PAYROLL. 5. Attach copies of insurance requirements of theater lease(s) (Theater Contracts). Are you assuming liability for Audience/Spectators? Yes No Attach copies of any other contract wherein you assume liability. 6. Are you responsible for parking areas, vendors or ticket collection? Yes No 7. Schedule Date Description Location Auditions Begin Rehearsal Begins First Public Performance Official Opening Earliest date on which construction of set or costume creation begins: 8. Theatrical Property Replacement Values: Set/Scenery: Props: Costumes/Wardrobe: Mechanical Winches, etc.: Lighting Equipment: Musical Instruments: On separate sheet, list any antique, object of art, furs, jewelry, or precious stones and metals. -

Theatrical Production Application

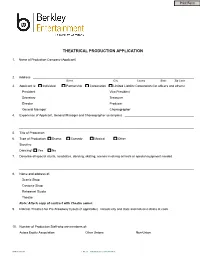

THEATRICAL PRODUCTION APPLICATION 1. Name of Production Company (Applicant) 2. Address Street City County State Zip Code 3. Applicant is: Individual Partnership Corporation Limited Liability Corporation (list officers and others) President Vice President Secretary Treasurer Director Producer General Manager Choreographer 4. Experience of Applicant, General Manager and Choreographer (examples) 5. Title of Production 6. Type of Production: Drama Comedy Musical Other Storyline Dancing? Yes No 7. Describe all special stunts, acrobatics, dancing, skating, scenes involving animals or special equipment needed. 8. Name and address of: Scenic Shop Costume Shop Rehearsal Studio Theatre Note: Attach copy of contract with Theatre owner. 9. Indicate Theatres for Pre-Broadway tryouts (if applicable). Include city and state and inclusive dates at each. 10. Number of Production Staff who are members of: Actors Equity Association Other Unions Non-Union APP E05 08 04 a W. R. BERKLEY COMPANY 11. Production Schedule (dates) Auditions Start Payroll Starts Rehearsals Start Theatre License Effective Construction of Sets Starts Preview Start Construction of Costumes Starts Opening Date/First Performance 12. If production is touring, complete the following: a. Number of performers b. Means of transportation of performers c. Means of transportation of property d. Are there any owned or long-term hire vehicles including buses and trucks? Yes No If yes, provide details. e. Name and Address of provider of driver(s) f. Does the insured use aircraft other than well known commercial airlines? Yes No If yes, provide details. Attach copy of itinerary showing dates, names and addresses of theatre and capacity. 13. For inspection, contact Phone No.