Native Riparian Vegetation in Tasmania 409

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Resolution of Campanulid Phylogeny, with Special Reference to the Placement of Dipsacales

TAXON 57 (1) • February 2008: 53–65 Winkworth & al. • Campanulid phylogeny MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS Toward a resolution of Campanulid phylogeny, with special reference to the placement of Dipsacales Richard C. Winkworth1,2, Johannes Lundberg3 & Michael J. Donoghue4 1 Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 11461–CEP 05422-970, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. [email protected] (author for correspondence) 2 Current address: School of Biology, Chemistry, and Environmental Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Private Bag, Laucala Campus, Suva, Fiji 3 Department of Phanerogamic Botany, The Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden 4 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208106, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106, U.S.A. Broad-scale phylogenetic analyses of the angiosperms and of the Asteridae have failed to confidently resolve relationships among the major lineages of the campanulid Asteridae (i.e., the euasterid II of APG II, 2003). To address this problem we assembled presently available sequences for a core set of 50 taxa, representing the diver- sity of the four largest lineages (Apiales, Aquifoliales, Asterales, Dipsacales) as well as the smaller “unplaced” groups (e.g., Bruniaceae, Paracryphiaceae, Columelliaceae). We constructed four data matrices for phylogenetic analysis: a chloroplast coding matrix (atpB, matK, ndhF, rbcL), a chloroplast non-coding matrix (rps16 intron, trnT-F region, trnV-atpE IGS), a combined chloroplast dataset (all seven chloroplast regions), and a combined genome matrix (seven chloroplast regions plus 18S and 26S rDNA). Bayesian analyses of these datasets using mixed substitution models produced often well-resolved and supported trees. -

Blue Tier Reserve Background Report 2016File

Background Report Blue Tier Reserve www.tasland.org.au Tasmanian Land Conservancy (2016). The Blue Tier Reserve Background Report. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Tasmania Australia. Copyright ©Tasmanian Land Conservancy The views expressed in this report are those of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy and not the Federal Government, State Government or any other entity. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquires concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Front Image: Myrtle rainforest on Blue Tier Reserve - Andy Townsend Contact Address Tasmanian Land Conservancy PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, 827 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay TAS 7005 | p: 03 6225 1399 | www.tasland.org.au Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 1 Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Location and Access ................................................................................................................................ 4 Bioregional Values and Reserve Status .................................................................................................. -

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY ON PRIVATE LAND SERIES Wattles of the City of Whittlesea Over a dozen species of wattle are indigenous to the City of Whittlesea and many other wattle species are commonly grown in gardens. Most of the indigenous species are commonly found in the forested hills and the native forests in the northern parts of the municipality, with some species persisting along country roadsides, in smaller reserves and along creeks. Wattles are truly amazing • Wattles have multiple uses for Australian plants indigenous peoples, with most species used for food, medicine • There are more wattle species than and/or tools. any other plant genus in Australia • Wattle seeds have very hard coats (over 1000 species and subspecies). which mean they can survive in the • Wattles, like peas, fix nitrogen in ground for decades, waiting for a the soil, making them excellent cool fire to stimulate germination. for developing gardens and in • Australia’s floral emblem is a wattle: revegetation projects. Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) • Many species of insects (including and this is one of Whittlesea’s local some butterflies) breed only on species specific species of wattles, making • In Victoria there is at least one them a central focus of biodiversity. wattle species in flower at all times • Wattle seeds and the insects of the year. In the Whittlesea attracted to wattle flowers are an area, there is an indigenous wattle important food source for most bird in flower from February to early species including Black Cockatoos December. and honeyeaters. Caterpillars of the Imperial Blue Butterfly are only found on wattles RB 3 Basic terminology • ‘Wattle’ = Acacia Wattle is the common name and Acacia the scientific name for this well-known group of similar / related species. -

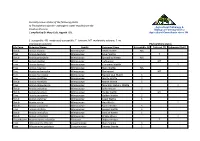

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and Related Scrub

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and related scrub Eucryphia lucida Vegetation Condition Benchmarks version 1 Rainforest and Related Scrub RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum peatland facies Community Description: Athrotaxis cupressoides (5–8 m) forms small woodland patches or appears as copses and scattered small trees. On the Central Plateau (and other dolerite areas such as Mount Field), broad poorly– drained valleys and small glacial depressions may contain scattered A. cupressoides trees and copses over Sphagnum cristatum bogs. In the treeless gaps, Sphagnum cristatum is usually overgrown by a combination of any of Richea scoparia, R. gunnii, Baloskion australe, Epacris gunnii and Gleichenia alpina. This is one of three benchmarks available for assessing the condition of RPW. This is the appropriate benchmark to use in assessing the condition of the Sphagnum facies of the listed Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland community (Schedule 3A, Nature Conservation Act 2002). Benchmarks: Length Component Cover % Height (m) DBH (cm) #/ha (m)/0.1 ha Canopy 10% - - - Large Trees - 6 20 5 Organic Litter 10% - Logs ≥ 10 - 2 Large Logs ≥ 10 Recruitment Continuous Understorey Life Forms LF code # Spp Cover % Immature tree IT 1 1 Medium shrub/small shrub S 3 30 Medium sedge/rush/sagg/lily MSR 2 10 Ground fern GF 1 1 Mosses and Lichens ML 1 70 Total 5 8 Last reviewed – 2 November 2016 Tasmanian Vegetation Monitoring and Mapping Program Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment http://www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/tasveg RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum facies Species lists: Canopy Tree Species Common Name Notes Athrotaxis cupressoides pencil pine Present as a sparse canopy Typical Understorey Species * Common Name LF Code Epacris gunnii coral heath S Richea scoparia scoparia S Richea gunnii bog candleheath S Astelia alpina pineapple grass MSR Baloskion australe southern cordrush MSR Gleichenia alpina dwarf coralfern GF Sphagnum cristatum sphagnum ML *This list is provided as a guide only. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids by Karen A. Johnson BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania February 2012 ii Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Karen A. Johnson Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for copying. Copying of any part of this thesis is prohibited for two years from the date this statement was signed; after that time limited copying is permitted in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Karen A. Johnson iii iv Abstract Relationships between plants and their pollinators are thought to have played a major role in the morphological diversification of angiosperms. The epacrids (subfamily Styphelioideae) comprise more than 550 species of woody plants ranging from small prostrate shrubs to temperate rainforest emergents. Their range extends from SE Asia through Oceania to Tierra del Fuego with their highest diversity in Australia. The overall aim of the thesis is to determine the relationships between epacrid floral features and potential pollinators, and assess the evolutionary status of any pollination syndromes. The main hypotheses were that flower characteristics relate to pollinators in predictable ways; and that there is convergent evolution in the development of pollination syndromes. -

An Investigation of Phyllode Variation in Acacia Verniciflua and A. Leprosa

CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/asb Australian Systematic Botany 18, 383–398 An investigation of phyllode variation in Acacia verniciflua and A. leprosa (Mimosaceae), and implications for taxonomy Stuart K. GardnerA, Daniel J. MurphyB,C, Edward NewbiginA, Andrew N. DrinnanA and Pauline Y. LadigesA ASchool of Botany, The University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010, Australia. BRoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Private Bag 2000, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Acacia verniciflua A.Cunn. and A. leprosa Sieber ex DC. are believed to be closely related, although strict interpretation of the current sectional classification of subgenus Phyllodineae places them in separate sections based on main nerve number. Six populations, comprised of the common and the southern variants of A. verniciflua and the large phyllode variant of A. leprosa, were sampled to test the value of nerve number as a taxonomic character and the current delimitation of these geographically variable species. Morphometrics, microscopy and the AFLP technique were used to compare and contrast populations. Phyllode nerve development was investigated and the abaxial nerve was found to be homologous with the mid-rib of a simple leaf. Three taxa were differentiated, two that are consistently two-nerved and one taxon that is variably one-nerved, two-nerved or both within a single plant. The first two-nerved taxon, characterised by smaller phyllodes, matches the type specimen of A. verniciflua. The second two-nerved taxon, characterised by large phyllodes, is apparently endemic to Mt William. The third taxon, with variable main nerve number, also has large phyllodes, and combines large phyllode variant A. -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Phytophthora Resistance and Susceptibility Stock List

Currently known status of the following plants to Phytophthora species - pathogenic water moulds from the Agricultural Pathology & Kingdom Protista. Biological Farming Service C ompiled by Dr Mary Cole, Agpath P/L. Agricultural Consultants since 1980 S=susceptible; MS=moderately susceptible; T= tolerant; MT=moderately tolerant; ?=no information available. Phytophthora status Life Form Botanical Name Family Common Name Susceptible (S) Tolerant (T) Unknown (UnK) Shrub Acacia brownii Mimosaceae Heath Wattle MS Tree Acacia dealbata Mimosaceae Silver Wattle T Shrub Acacia genistifolia Mimosaceae Spreading Wattle MS Tree Acacia implexa Mimosaceae Lightwood MT Tree Acacia leprosa Mimosaceae Cinnamon Wattle ? Tree Acacia mearnsii Mimosaceae Black Wattle MS Tree Acacia melanoxylon Mimosaceae Blackwood MT Tree Acacia mucronata Mimosaceae Narrow Leaf Wattle S Tree Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Shrub Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Tree Acacia obliquinervia Mimosaceae Mountain Hickory Wattle ? Shrub Acacia oxycedrus Mimosaceae Spike Wattle S Shrub Acacia paradoxa Mimosaceae Hedge Wattle MT Tree Acacia pycnantha Mimosaceae Golden Wattle S Shrub Acacia sophorae Mimosaceae Coast Wattle S Shrub Acacia stricta Mimosaceae Hop Wattle ? Shrubs Acacia suaveolens Mimosaceae Sweet Wattle S Tree Acacia ulicifolia Mimosaceae Juniper Wattle S Shrub Acacia verniciflua Mimosaceae Varnish wattle S Shrub Acacia verticillata Mimosaceae Prickly Moses ? Groundcover Acaena novae-zelandiae Rosaceae Bidgee-Widgee T Tree Allocasuarina littoralis Casuarinaceae Black Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina paludosa Casuarinaceae Swamp Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina verticillata Casuarinaceae Drooping Sheoak S Sedge Amperea xipchoclada Euphorbaceae Broom Spurge S Grass Amphibromus neesii Poaceae Swamp Wallaby Grass ? Shrub Aotus ericoides Papillionaceae Common Aotus S Groundcover Apium prostratum Apiaceae Sea Celery MS Herb Arthropodium milleflorum Asparagaceae Pale Vanilla Lily S? Herb Arthropodium strictum Asparagaceae Chocolate Lily S? Shrub Atriplex paludosa ssp. -

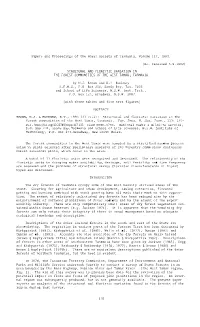

Structural and Floristic Variation in the Forest Communities of the West Tamar, Tasmania

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 117, 1983. [ms. received 3.9.1982) STRUCTURAL AND FLORISTIC VARIATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF THE WEST TAMAR, TASMANIA. by M.J. Brown and R.T. Buckney N.P.W.S., P.O. Box 210, Sandy Bay, Tas. 7005 and School of Life Sciences, N.S.W. Inst. Tech., P.O. Box 123, Broadway, N.S.W. 2007. (with three tables and five text-figures) ABSTRACT BROWN, M.J. & BUCKNEY, R.T., 1983 (31 viii): Structural and floristic variation in the forest communities of the West Tamar, Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm., 117: 135- 152. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.117.135 ISSN 0080-4703. National Parks & Wildlife Service, P.O. Box 210, Sandy Bay, Tasmania and School of Life Sciences, N.S.W. Institute of Technology, P.O. Box 123, Broadway, New South Wales. The forest communities in the West Tamar were sampled by a stratified random process using 55 plots selected after preliminary analy sis of 243 Forestry Commission continuous forest inventory plots, which occur in the area. A total of 13 floristic units were recognised and described. The relationship of the floristic units to changing water availability, drainage, soil fertility and fire frequency are assessed and the problems of structural versus floristic classifications of forest types are discussed. INTRODUCTION The dry forests of Tasmania occupy some of the most heavily utilised areas of the state. Clearing for agriculture and urban development, sawlog extraction, firewood getting and burning combined with stock grazing have all made their mark on this vegeta tion. -

Tasmania - from the Wet West to the Dry East

This collection is maintained with the assistance of the Tasmania - from the wet west to the dry east. Regional Branch of the Australian Plant Society. Influences on the development of the Tasmanian plant mix Montane moorland and cool oceanic heathland When Gondwana existed as a super Geology of Tasmania Vegetation Map of Tasmania The Tasmanian highland vegetation developed in isolation from the Australian Alps. Even during ice continent, Australia and Tasmania, Africa, ages, hundreds of kilometres of lowland vegetation separated the two high altitude environments. South America, New Zealand and Antarctica shared many plant families and some Montane plants have to cope with wide temperature fluctuations, with periods of below 0°C and Genera. exposure to winds. Cold may be prolonged if the ground freezes. Plants may be blanketed by snow or BASS STRAIT the mountains by cloud. Snowmelt or clear weather can cause intense rays of light, resulting in high For example, the protea family has members temperature. Wind or sun can dry the plant and soil. in all those land masses except Antarctica. The Southern Africa panel covers the protea family more fully. Plants require moisture and warmth. Small hard leaves offer Tasmania was the last land mass to break protection from the drying away from Antarctica. The opening of the effects of sun and wind. Low gap between these land masses allowed the ocean to circulate growth avoids wind. Branches around Antarctica, cooling the earth’s climate and so locking up grow close together to shelter vast quantities of water as ice. the parts of each plant.