A Korean/American Epistemology a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

Police Prosecutions and Punitive Instincts

Washington University Law Review Volume 98 Issue 4 2021 Police Prosecutions and Punitive Instincts Kate Levine Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Kate Levine, Police Prosecutions and Punitive Instincts, 98 WASH. U. L. REV. 0997 (2021). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol98/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Law Review VOLUME 98 NUMBER 4 2021 POLICE PROSECUTIONS AND PUNITIVE INSTINCTS KATE LEVINE* ABSTRACT This Article makes two contributions to the fields of policing and criminal legal scholarship. First, it sounds a cautionary note about the use of individual prosecutions to remedy police brutality. It argues that the calls for ways to ease the path to more police prosecutions from legal scholars, reformers, and advocates who, at the same time, advocate for a dramatic reduction of the criminal legal system’s footprint, are deeply problematic. It shows that police prosecutions legitimize the criminal legal system while at the same time displaying the same racism and ineffectiveness that have been shown to pervade our prison-backed criminal machinery. The Article looks at three recent trials and convictions of police officers of color, Peter Liang, Mohammed Noor, and Nouman Raja, in order to underscore the argument that the criminal legal system’s race problems are * Associate Professor of Law, Benjamin N. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

Racing the Pandemic: Anti-Asian Racism Amid COVID-19

9 Racing the Pandemic Anti-Asian Racism amid COVID-19 Christine R. Yano How does race shape the experience of the current and ongoing global pandemic? How does the pandemic shape the experience of race—in politics and in everyday lives? How have histories of racialization and racism in the United States and elsewhere allowed for the targeting of Asian Americans? How might we develop effective strategies that counter xenophobic racisms surrounding COVID-19? And in an ideal world seeking meaningful change, how might critical empathy—that is, reaching out to others with hearts, minds, bodies, and actions—play a crucial role?1 These questions structure my approach to discussing anti-Asian racism amid the pandemic with the goal of developing strategies of action for the targets of such racism, as well as for others for whom race-based violence is anathema. The Black Lives Matter movement has compelled us to thoughts and actions at a time when systemic racism can no longer be ignored. What the movement reminds us of is the ongoing salience of race as a basis for institutionalized and interpersonal actions, as these shape overt macroaggressions as well as more covert microaggressions. “China virus.” “Wuhan virus.” “Kung-flu.” These labels, uttered by people at the highest political echelons of the United States during one of the worst public health disasters within most people’s lifetimes, give permission for racial discrimination and violence, bringing anti-Asian racism into public light once again. Yellow Peril rears its ugly head—in earlier periods as a fear of Asians invading white worlds, 124 : THE PANDEMIC: PERSPECTIVES ON ASIA and here as an epidemiological fear of an Asian virus unleashed upon the world.2 In the words of psychiatrist Ravi Chandra, these pandemic labels, especially uttered by those in power, “disinhibit” the public from racist emotions and expressions.3 In using the term “disinhibit,” Chandra implies that anti-Asian racism lurks historically and broadly just below the surface, suppressed in the name of more rational or humane discourse. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

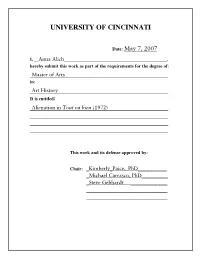

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

Feduni Researchonline Copyright Notice

FedUni ResearchOnline https://researchonline.federation.edu.au Copyright Notice This is an original manuscript/preprint of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Continuum in September 2020, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1782838 CRICOS 00103D RTO 4909 Page 1 of 1 Comic investigation and genre-mixing: the television docucomedies of Lawrence Leung, Judith Lucy and Luke McGregor Lesley Speed In the twenty-first century, comedians have come to serve as public commentators. This article examines the relationship between genre-mixing and cultural commentary in four documentary series produced for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that centre on established comedians. These series are Lawrence Leung’s Choose Your Own Adventure (2009), Judith Lucy’s Spiritual Journey (2011), Judith Lucy is All Woman (2015) and Luke Warm Sex (2016). Each series combines the documentary and comedy genres by centring on a comedian’s investigation of a theme such as spirituality, gender or sex. While appearing alongside news satire, these docucomedies depart from the latter by eschewing politics in favour of existential themes. Embracing conventions of personalized documentaries, these series use performance reflexively to draw attention to therapeutic discourses and awkward situations. Giving expression to uncertain and questioning views of contemporary spirituality, gender and mediated intimacies, the docucomedies of Lawrence Leung, Judith Lucy and Luke McGregor stage interventions in contemporary debates that constitute forms of public pedagogy. Documentary comedy These series can be identified as documentary comedies, or docucomedies, which combine humour and non-fiction representation without adhering primarily to either genre. Although the relationship between comedy and factual screen works has received little sustained attention, notes Paul Ward, a program can combine both genres (2005, 67, 78–9). -

Neo-Realism Meets the Blues in Charles Burnett's Killer

NEO-REALISM MEETS THE BLUES IN CHARLES BURNETT’S KILLER OF SHEEP Keith Mehlinger Morgan State University “…the very existence of the blues tradition is irrefutable evidence that those who evol- ved it respond to the vicissitudes of the human condition not with hysterics and desperation, but through the wisdom of poetry informed by pragmatic insight” (Murray, 1996: 208-209). Although little known outside of critics’ circles and dedicated cineastes, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977) “remains to this day a near mythic object, one of the first fifty films inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry” (Foundas, Independent Lens: Charles Burnett, in Kapsis (ed.) 2011:138). The film “tenderly recounts a few days in the life of a slaughterhouse worker, Stan (Henry G. Sanders), whose existence is as bounded by invisible threads of hopelessness as that of the sheep that he is forced to kill each day” (Hozic, The House I live In: An Interview with Charles Burnett, in Kapsis, 2011: 75). During its brief theatri- cal release in 1977, the New York Times critic Janet Maslin dismissed Killer of Sheep as “ama- teurish” and ‘boring’. Since then, the film has won awards at festivals and “acquired honorary protection by the National Film Registry accorded to a select few ‘masterpieces’ such as Citi- zen Kane, and aided its author in winning a prestigious John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellowship”, popularly known as the “genius award” (Hozic, 2011: 75). In addition to being selected as one of America’s fifty most culturally significant films, the film was named one of the “100 Most Influential Films of All Time” by the National Society of Film and gained critical acclaim in Europe. -

THE Permanent Crisis of FILM Criticism

mattias FILM THEORY FILM THEORY the PermaNENT Crisis of IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY film CritiCism frey the ANXiety of AUthority mattias frey Film criticism is in crisis. Dwelling on the Kingdom, and the United States to dem the many film journalists made redundant at onstrate that film criticism has, since its P newspapers, magazines, and other “old origins, always found itself in crisis. The erma media” in past years, commentators need to assert critical authority and have voiced existential questions about anxieties over challenges to that author N E the purpose and worth of the profession ity are longstanding concerns; indeed, N T in the age of WordPress blogospheres these issues have animated and choreo C and proclaimed the “death of the critic.” graphed the trajectory of international risis Bemoaning the current anarchy of inter film criticism since its origins. net amateurs and the lack of authorita of tive critics, many journalists and acade Mattias Frey is Senior Lecturer in Film at film mics claim that in the digital age, cultural the University of Kent, author of Postwall commentary has become dumbed down German Cinema: History, Film History, C and fragmented into niche markets. and Cinephilia, coeditor of Cine-Ethics: riti Arguing against these claims, this book Ethical Dimensions of Film Theory, Prac- C examines the history of film critical dis tice, and Spectatorship, and editor of the ism course in France, Germany, the United journal Film Studies. AUP.nl 9789089647177 9789089648167 The Permanent Crisis of Film Criticism Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical founda- tions of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory.