Copyright by Amy Kathleen Guenther 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Pledge Allegiance to the Embroidered Scarlet

I PLEDGE ALLEGIANCE TO THE EMBROIDERED SCARLET LETTER AND THE BARBARIC WHITE LEG ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University Dominguez Hills ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Humanities ____________ by Laura J. Ford Spring 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the people who encouraged and assisted me as I worked towards completing my master’s thesis. First, I would like to thank Dr. Patricia Cherin, whose optimism, enthusiasm, and vision kept me moving toward a graduation date. Her encouragement as my thesis committee chair inspired me to work diligently towards completion. I am grateful to Abe Ravitz and Benito Gomez for being on my committee. Their thoughts and advice on the topics of American literature and film have been insightful and useful to my research. I would also like to thank my good friend, Caryn Houghton, who inspired me to start working on my master’s degree. Her assistance and encouragement helped me find time to work on my thesis despite overwhelming personal issues. I thank also my siblings, Brad Garren, and Jane Fawcett, who listened, loved and gave me the gift of quality time and encouragement. Other friends that helped me to complete this project in big and small ways include, Jenne Paddock, Lisa Morelock, Michelle Keliikuli, Michelle Blimes, Karma Whiting, Mark Lipset, and Shawn Chang. And, of course, I would like to thank my four beautiful children, Makena, T.K., Emerald, and Summer. They have taught me patience, love, and faith. They give me hope to keep living and keep trying. -

Andrea Von Foerster Music Supervisor

ANDREA VON FOERSTER MUSIC SUPERVISOR MOTION PICTURES FANTASTIC FOUR Kevin Feige, Matthew Vaughn, Simon Kinberg, 20 th Century Fox Hutch Parker, Gregory Goodman, prods. Joshua Trunk, dir. GREATER Brian Reindl, prod. Blue Ribbon Digital Media David Hunt, dir. HELICOPTER MOM Salome Breziner, Josh Cole, Stephen Israel, American Film Productions J.M.R. Luna, prods. Salome Breziner, dir. NAOMI AND ELY’S NO KISS LIST Robert Abramoff, Kristin Hanggi, Alexandra 20 th Century Fox Milchan, Emily Gerson Saines, prods. Kristin Hanggi, dir. SATURN RETURNS Anselm Clinard, Gregory Lemkin, Shawn Moonrise Pictures Tolleson, prods. Shawn Tolleson, dir. 1:30 TRAIN Howard Baldwin, Karen Elise Baldwin, G4 Productions Chris Evans, William Immerman, prods. Chris Evans, dir. GRACE OF A STRANGER (short) Troy Hollar, prod / dir. Lovemakers WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS Justin X. Duprie, Brian Udovich, prods. PLACE Zeke Hawkins, Simon Hawkins, dirs. Rough & Tumble Films A GIRL AND A GUN Liz Federowicz, Filip Jan Rymsza, Thomas Royal Road Entertainment D. Adelman, Brent Travers, prods. Filip Jan Rymsza, dir. DEVIL’S DUE John Davis, prod. 20 th Century Fox Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, Tyler Gillett, dirs. TIME LAPSE B.P. Cooper, Rick Montgomery, prods. Veritas Productions Bradley King, dir. SEA OF DARKNESS Salome Breziner, prod. Concrete Images Michael Oblowitz, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 ANDREA VON FOERSTER MUSIC SUPERVISOR BEGIN AGAIN Judd Apatow, Sam Hoffman, Ben Nearn, Exclusive Media Group Tom Rice, exec. prods. John Carney, dir. NO CLUE Brent Butt, Laura Lightbown, prods. Sparrow Media Carl Bessai, dir. GROWING UP AND OTHER LIES Nicole Diane Lederman, Katie Mustard, Embark Productions / Gold Apple Jason Weiss, prods. -

Acting Resume

Chip Chinery COMMERCIALS: AKA TALENT AGENCY: 323-965-5600 THEATRICAL & VOICE OVER: IMPERIUM 7 AGENCY: 323-931-9099 Auburn Hair Brown Eyes SAG-AFTRA www.chipchinery.com Chip’s Cell/Text Machine: 818-793-4329 FILM BATTLE OF THE SEXES Roone Arledge Dir: Jonathan Dayton & Valerie Faris THE OLD MAN & THE STUDIO Co-Star Dir: Eric Champnella PH2: PEARLMAGEDDON Co-Star Dir: Rob Moniot THE COUNTRY BEARS Featured Dir: Peter Hastings COYOTE UGLY Featured Dir: David McNally SPACE COWBOYS Featured Dir: Clint Eastwood ROCKY & BULLWINKLE Featured Dir: Des McAnuff DILL SCALLION Featured Dir: Jordan Brady TELEVISION THE UPSHAWS Malcolm Netflix / Dir. Sheldon Epps THE CONNERS Tony ABC / Dir. Gail Mancuso SHAMELESS Larry Seaver SHOWTIME / Dir. Loren Yaconelli HOMECOMING Sawyer (recurring) AMAZON / Dir. Kyle Patrick Alvarez LIKE MAGIC Club Announcer NBC / Dir. Julie Anne Robinson GOOD GIRLS The Mattress King NBC / Dir. Michael Weaver THE GOLDBERGS Dancing Bruce ABC / Dir. Lew Schneider THE BIG BANG THEORY Bob The Boat Neighbor CBS / Dir. Mark Cendrowski THE KIDS ARE ALRIGHT Bob Parson ABC / Dir. Matt Sohn I FEEL BAD Officer Young NBC / Dir. Tristram Shapeero FAM Race Track Announcer CBS / Dir. Victor Gonzalez NEW GIRL Ben FOX / Dir. Josh Greenbaum LIFE IN PIECES Dustin CBS / Dir. John Riggi BROOKLYN NINE-NINE Don ABC / Dir. Kat Coiro SPEECHLESS Mr. McHugh ABC / Dir. Christine Gernon AMERICAN HORROR STORY Leland Candoli FX / Dir. Brad Buecker NCIS NCIS Agent Rodney Spence CBS / Dir.Tony Wharmby CHELSEA White Collar Comedy Tour Netflix / Dir.Rik Reinholdtsen MOM Dave CBS / Dir. James Widdoes THE MIDDLE Guest Starring ABC / Dir. Blake Evans ANGER MANAGEMENT Guest Starring FX / Dir. -

Laura Interval. Height 175 Cm

Actor Biography Laura Interval. Height 175 cm Feature Film. 2009 Hit To Right Laura Aria Productions Dir. Dave Coleman 2004 Room 314 Tammy Care 7A Productions Dir. Michael Knowles 1997 Spawn Angela New Line Pictures Dir. Mark Dippe 1996 Under The Influence Patti Dir. Eric Gardner 1994 Automatic Mother Dir. John Murlowski Television. 2009 The Cult Morgan Great Southern Television (Guest Role) Dir. Peter Berger 2008 New Amsterdam Kayla Moore FOX (Guest) Dir. Matt Penn 2008 Law & Order June Doherty NBC (Guest) Dir. Mark Levin 2007 One Life To Live Claire ABC (Recurring Guest) Dir. Frank Valentini 2007 The Book Of Daniel Joan Warwick NBC (Guest) Dir. Perry Lang 2006 Jake In Progress Carol ABC (Guest) Dir. Jeff Melman PO Box 78340, Grey Lynn, www.johnsonlaird.com Tel +64 9 376 0882 Auckland 1245, NewZealand. www.johnsonlaird.co.nz Fax +64 9 378 0881 Laura Interval. Page 2 Television continued... 2005 Third Watch Karen Daniels NBC (Guest) Dir. Nelson McCormick 2005 Law & Order: CI Sydney NBC (Guest) Dir. Steve Shill 2005 Stella (Pilot) Libby Green Comedy Central (Core Cast) Dir. David Wain 2004 Star Trek Enterprise Veylo UPN (Guest) Dir. Levar Burton 2002 Law & Order: SVU Darlene Wilmont NBC (Guest) Dir. Jean DeSegonzac 2001 Sex & The City Tricia Wilson HBO (Guest) Dir. Michael Spiller 2001 The Mike O'Malley Show Patricia NBC (Guest) Dir. Jamie Widdoes 2000 Early Edition Deb Frawley CBS (Guest) Dir. Scott Paulin 2000 Star Trek: Voyager Erin Hanson UPN (Guest) Dir. Cliff Bole 1999 Wind On Water Claudia NBC (Recurring Guest) Dir. Arthur Forney 1999 Some Guys (Pilot) Samantha ABC (Core Cast) Dir. -

Premiere-Passion-Dospress.Pdf

2 À la recherche de From the Manger to the Cross le chaînon manquant entre 1000 ans de peinture religieuse et 100 ans de représentation du Christ au cinéma PREMIÈRE PASSION documentaire / 1 x 54’ / 2010 un film écrit et réalisé par Philippe Baron avec les voix de Catherine Riaux / Gilles Roncin conseiller historique Michel Derrien documentaliste Mirabelle Fréville image Philippe Elusse / Philippe Baron / Fabrice Richard / Christophe Cocherie son Pierrick Cohéléach montage Stéphanie Langlois design sonore Yan Volsy mixage Mathieu Tiger musique originale Yan Volsy / Bertrand Larmet direction de production Sabine Jaffrennou / Aurélie Angebault administration de production Valérie Malavieille produit par Jean-François Le Corre producteurs associés Mathieu Courtois / Serge Bromberg une coproduction Vivement Lundi ! / Blink Productions / Télénantes / AVRO avec la participation de CinéCinéma / France Télévisions Corse ViaStella / CNC / Région Bretagne / Région Pays de la Loire / Procirep / Angoa / Programme MEDIA de l’Union Européenne 3 Résumé remière vie de Jésus au cinéma, From the Manger to the Cross (De la crèche à la croix) est la seule P Passion jamais tournée sur les lieux mêmes décrits par les Evangiles, en Palestine. Ce tournage-là fut une véritable épopée : 18 760 kilomètres parcourus dans des paquebots de toutes tailles, plus de 5 100 miles en train et des centaines à dos d’ânes, de chameaux ou de chevaux ; scènes d’hystérie quand un Christ portant sa croix se promène dans les rues de Jérusalem, attaque de brigands… Le film, 4e long métrage de l’histoire du cinéma diffusé il y a presque un siècle, fut un succès commercial. Pourtant, tout le monde a oublié le nom de son auteur : Sidney Olcott. -

Irish Film Institute What Happened After? 15

Irish Film Studyguide Tony Tracy Contents SECTION ONE A brief history of Irish film 3 Recurring Themes 6 SECTION TWO Inside I’m Dancing INTRODUCTION Cast & Synopsis 7 This studyguide has been devised to accompany the Irish film strand of our Transition Year Moving Image Module, the pilot project of the Story and Structure 7 Arts Council Working Group on Film and Young People. In keeping Key Scene Analysis I 7 with TY Guidelines which suggest a curriculum that relates to the Themes 8 world outside school, this strand offers students and teachers an opportunity to engage with and question various representations Key Scene Analysis II 9 of Ireland on screen. The guide commences with a brief history Student Worksheet 11 of the film industry in Ireland, highlighting recurrent themes and stories as well as mentioning key figures. Detailed analyses of two films – Bloody Sunday Inside I'm Dancing and Bloody Sunday – follow, along with student worksheets. Finally, Lenny Abrahamson, director of the highly Cast & Synopsis 12 successful Adam & Paul, gives an illuminating interview in which he Making & Filming History 12/13 outlines the background to the story, his approach as a filmmaker and Characters 13/14 his response to the film’s achievements. We hope you find this guide a useful and stimulating accompaniment to your teaching of Irish film. Key Scene Analysis 14 Alicia McGivern Style 15 Irish FIlm Institute What happened after? 15 References 16 WRITER – TONY TRACY Student Worksheet 17 Tony Tracy was former Senior Education Officer at the Irish Film Institute. During his time at IFI, he wrote the very popular Adam & Paul Introduction to Film Studies as well as notes for teachers on a range Interview with Lenny Abrahamson, director 18 of films including My Left Foot, The Third Man, and French Cinema. -

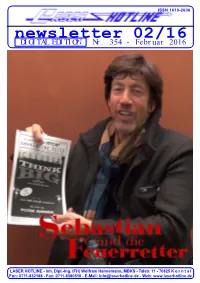

Newsletter 02/16 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 02/16 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 354 - Februar 2016 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 02/16 (Nr. 354) Februar 2016 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Kennen Sie den Mann auf dem Titel- bild? Nein? Aber bestimmt kennen Sie ein paar seiner Filme. Denn Christian Duguay hat schon einige handfeste Action-Filme inszeniert, wie beispiels- Eine kurze Information an alle Cinera- Zu guter Letzt möchten wir gerne noch weise THE ART OF WAR, ma-Fans, die ungeduldig auf die noch Ihren Blick auf die nächste Seite len- HYDROTOXIN oder SCREAMERS. fehlenden beiden Titel CINERAMA’S ken. Denn dort spricht unsere Kolum- Vor zwei Wochen hatten wir Gelegen- RUSSIAN ADVENTURE und THE nistin Anna wieder einmal mit Holly- heit, uns mit dem gebürtigen Kanadier BEST OF CINERAMA warten. Flicker wood. Ihre Kolumne steht dabei dieses in Stuttgart zu unterhalten. Denn ge- Alley wird diese beiden DVD/BD- Mal ganz im Zeichen des Valentinstags. nau dort stellte der renommiere Regis- Releases nicht vor Herbst veröffentli- Wir haben uns jedenfalls beim Lesen seur seinen neuesten Film, den packen- chen. Hauptgrund dafür ist die schöne des Textes großartig amüsiert. Und den Abenteuerfilm SEBASTIAN UND Tatsache, dass man bei RUSSIAN jetzt Sie dran! DIE FEUERRETTER, dem begeisterten ADVENTURE unverhofft auf die Publikum persönlich vor. Natürlich hat- Originalnegative gestoßen ist und sich Ihr Laser Hotline Team ten wir wieder unsere Kamera vor Ort Experte David Strohmaier der besseren und haben das alles für Sie in Bild und Qualität wegen für eine komplette Ton festgehalten. -

Thom Williams

Thom Williams Gender: Male Service: 818-501-5225 (ISA) Height: 6 ft. 1 in. Mobile: 818-749-8904 Weight: 275 pounds E-mail: [email protected] Birthdate: 11/16/1973 Web Site: http://ISAstunts.com... Eyes: Blue Hair Length: Short Waist: 42 Inseam: 31 Shoe Size: 12 Physique: Muscluar / Heavyset Coat/Dress Size: 52L Ethnicity: Caucasian / White, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern Photos Film Credits The Great Wall Coordinator, Motion Capture Unit Office Christmas Party Stunt Performer / Stunts Sully Stunt Performer Jason Bourne Stunt Perfomer The Accountant Stunt Driver The Lone Ranger Stunt Double - W. Earl Brown Tommy Harper To Have and To Hold 2nd Unit Director, Stunt THTH, LLC/Ray Bengston Generated on 09/29/2021 02:50:36 pm Page 1 of 6 Coordinator Spider-Man Reboot Stunt Fighter Andy Armstrong Horrible Bosses Stunt Performer Merritt Yohnka Firebird Stunt Coordinator Dir - Brent McCorkle J. Edgar Motion Capture Performer Clint Eastwood / Michael Owens / Michelle Ladd Hereafter Stunt Coordinator (MoCap Unit) Warner Bros. / Clint Eastwood Green Lantern Stunt Performer Gary Powell Unstoppable Stunt Double - Ethan Suplee Gary Powell Red Dawn Motion Capture Director MGM The Book of Eli Stunt Performer Jeff Imada Invictus Motion Capture Director Warner Bros. / Clint Eastwood Highway Stunt Performer Rob King Blood Shot Stunt Performer Tim Sitarz The Rundown Stunt Performer Andy Cheng Starsky & Hutch Stunt Double - Chris Penn Dennis Scott / Gary Davis The Day After Tomorrow Stunt Performer Charlie Brewer No Rules Stunt Performer Will Leong The Longest -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams The following is a list of films directly related to my research for this book. There is a more extensive list for Lucile in Randy Bryan Bigham, Lucile: Her Life by Design (San Francisco and Dallas: MacEvie Press Group, 2012). Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon The American Princess (Kalem, 1913, dir. Marshall Neilan) Our Mutual Girl (Mutual, 1914) serial, visit to Lucile’s dress shop in two episodes The Perils of Pauline (Pathé, 1914, dir. Louis Gasnier), serial The Theft of the Crown Jewels (Kalem, 1914) The High Road (Rolfe Photoplays, 1915, dir. John Noble) The Spendthrift (George Kleine, 1915, dir. Walter Edwin), one scene shot in Lucile’s dress shop and her models Hebe White, Phyllis, and Dolores all appear Gloria’s Romance (George Klein, 1916, dir. Colin Campbell), serial The Misleading Lady (Essanay Film Mfg. Corp., 1916, dir. Arthur Berthelet) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Film Corp., 1917, dir. Marshall Neilan) The Rise of Susan (World Film Corp., 1916, dir. S.E.V. Taylor), serial The Strange Case of Mary Page (Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, 1916, dir. J. Charles Haydon), serial The Whirl of Life (Cort Film Corporation, 1915, dir. Oliver D. Bailey) Martha’s Vindication (Fine Arts Film Company, 1916, dir. Chester M. Franklin, Sydney Franklin) The High Cost of Living (J.R. Bray Studios, 1916, dir. Ashley Miller) Patria (International Film Service Company, 1916–17, dir. Jacques Jaccard), dressed Irene Castle The Little American (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. Cecil B. DeMille) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. -

DOROTTYA JÁSZAY, ANDREA VELICH Eötvös Loránd University

Film & Culture edited by: DOROTTYA JÁSZAY, ANDREA VELICH Eötvös Loránd University | Faculty of Humanities | School of English and American Studies 2016 Film & Culture Edited by: DOROTTYA JÁSZAY, ANDREA VELICH Layout design by: BENCE LEVENTE BODÓ Proofreader: ANDREA THURMER © AUTHORS 2016, © EDITORS 2016 ISBN 978-963-284-757-3 EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM Supported by the Higher Education Restructuring Fund | Allocated to ELTE by the Hungarian Government 2016 FILM & CULTURE Marcell Gellért | Shakespeare on Film: Romeo and Table of Juliet Revisioned 75 Márta Hargitai | Hitchcock’s Macbeth 87 Contents Dorottya Holló | Culture(s) Through Films: Learning Opportunities 110 Géza Kállay | Introduction: Being Film 5 János Kenyeres | Multiculturalism, History and Identity in Canadian Film: Atom Egoyan’s Vera Benczik & Natália Pikli | James Bond in the Ararat 124 Classroom 19 Zsolt Komáromy | The Miraculous Life of Henry Zsolt Czigányik | Utopia and Dystopia Purcell: On the Cultural Historical Contexts of on the Screen 30 the Film England, my England 143 Ákos Farkas | Henry James in the Cinema: When Miklós Lojkó | The British Documentary Film the Adapters Turn the Screw 44 Movement from the mid-1920s to the mid-1940s: Its Social, Political, and Aesthetic Context 155 Cecilia Gall | Representation of Australian Aborigines in Australian film 62 Éva Péteri | John Huston’s Adaptation of James Joyce’s “The Dead”: A Literary Approach 186 FILM & CULTURE Eglantina Remport & Janina Vesztergom | Romantic Ireland and the Hollywood Film Industry: The Colleen -

Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This Page Intentionally Left Blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema

Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This page intentionally left blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema From Cimarron to Citizen Kane J. E. Smyth THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2006 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smyth, J. E., 1977- Reconstructing American historical cinema : from Cimarron to Citizen Kane / J. E. Smyth. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-2406-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8131-2406-9 (alk. paper) 1. Historical films--United States--History and criticism. 2. Motion pictures and history. I. Title. PN1995.9.H5S57 2006 791.43’658--dc22 2006020064 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. Manufactured in the United States of America. Member of the Association of American University Presses For Evelyn M. Smyth and Peter B. Smyth and for K. H. and C.