Electroacoustic Music and Popular Culture Interacting: Aesthetic And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

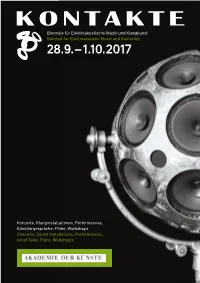

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

Ut Contemporary Music Festival

UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL WEDNESDAY, MARCH 4 MORNING PRESENTATIONS 9 a.m. HMC 244 Aaron Hunt - 9:05 - 9:25 a.m. "Rhythmic Hypnosis: A Theory of Rhythm and Meter in the Music of Tool" Fabio Fabbri - 9:30 - 10:05 a.m. "Techniques and Terminology for the Analysis of Electroacoustic Music and More" Ian Evans Guthrie - 10:10 - 10:30 a.m. “Rhythm as a Function" Robert Strobel - 10:35 a.m. - 11 a.m. "The Dangers of Excessive Conceptuality in Theory and Composition" EMILY KOH AND TRAVIS ALFORD PRESENTATIONS 2 - 4 p.m. HMC 110 CONCERT ONE 6 - 7:30 p.m. Sandra G. Powell Recital Hall The Outside Mark Engebretson Mark Engebretson, alto saxophone postcards Chin Ting Chan Yu-Fang Chen, violin Finding the Right Words Aaron Hunt Vicki Leona, percussion UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL Lemoncholy Gabriel Brady Gabriel Brady, piano LIGO Alissa Voth Bethany Padgett, flute Kae So Wae Train Vicki Leona Turner McCabbe and Vicki Leona, percussion Cullen Burke, Aaron Hunt, and Claire Terrell, perspectives (voice) one final gyre Alex Burtzos Allison Adams and Corey Martin, saxophone THURSDAY, MARCH 5 CONCERT TWO 11 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. Sandra G. Powell Recital Hall A Farewell Elegy Ian Evans Guthrie Ian Evans Guthrie, piano Breathe Slow, Breathe Deep Ed Martin Jeri-Mae G. Astolfi, piano Ctrl C Adam Stanovic fixed media Isaac's World Filipe Leitao fixed media Missing Memories John Baxter John Baxter, piano UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL London 2012 Hunter Prueger Hunter Prueger , alto saxophone Confab Andrew Hannon Joseph Brown, trombone RITA D'ARCANGELO FLUTE MASTERCLASS 12:40 - 1:55 p.m. -

A Method for the Transcription and Analysis of Electroacoustic Music

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Emerging Musical Structures: A method for the transcription and analysis of Electroacoustic Music Mario Mazzoli Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/71 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EMERGING MUSICAL STRUCTURES: A METHOD FOR THE TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC. by MARIO MAZZOLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 MARIO MAZZOLI All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ _________________________ Date Professor Jeff Nichols Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _________________________ Date Professor Norman Carey Executive Officer Distinguished Professor Joseph N. Straus Professor Mark Anson-Cartwright Professor David Olan Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract EMERGING MUSICAL STRUCTURES: A METHOD FOR THE TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC. by MARIO MAZZOLI Advisor: Distinguished Professor Joseph N. Straus This dissertation proposes a method for transcribing “electroacoustic” music, and subsequently a number of methods for its analysis, utilizing the transcription as main ground for investigation. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Editorial: Alternative Histories of Electroacoustic Music

This is a repository copy of Editorial: Alternative histories of electroacoustic music. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/119074/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Mooney, J orcid.org/0000-0002-7925-9634, Schampaert, D and Boon, T (2017) Editorial: Alternative histories of electroacoustic music. Organised Sound, 22 (02). pp. 143-149. ISSN 1355-7718 https://doi.org/10.1017/S135577181700005X This article has been published in a revised form in Organised Sound http://doi.org/10.1017/S135577181700005X. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ EDITORIAL: Alternative Histories of Electroacoustic Music In the more than twenty years of its existence, Organised Sound has rarely focussed on issues of history and historiography in electroacoustic music research. -

Ryuichi Sakamoto Discography 19782012

Ryuichi Sakamoto Discography 19782012 1 / 4 Ryuichi Sakamoto Discography 19782012 2 / 4 3 / 4 Ryuichi Sakamoto Discography 1978-2012. 2011 Fennesz & Ryuichi Sakamoto Flumina 2011 Alva Noto & Ryuichi Sakamoto Summvs.. Upload:, 04:58 202 Artist: Ryuichi Sakamoto Title Of Album: Discography Year Of Release: 1978-2012 Genre: Modern Classical, Electronic, .... Artist Ryuichi Sakamoto Title Of Album Discography Year Of Release 1978-2012 Genre Modern Classical, Electronic, Experimental, Jazz, .... Ryuichi Sakamoto - Discography (1978-2012)http://bit.ly/2tPHUtq.. Artist: Ryuichi Sakamoto Title Of Album: Discography Year Of Release: 1978-2012. Genre: Modern Classical, Electronic, Experimental, Jazz, J‑pop, New Wave, .... Ryuichi Sakamoto Discography Download Average ratng: 4,7/5 6409 ... Download Ryuichi Sakamoto - Discography (1978-2012) Mp3 or any .... 1990 The Sheltering Sky http://sxmlaboraffairs.com/lossless- music/319705-ryuichi-sakamoto-discography-1978-2012-a.html.. Ryuichi Sakamoto Discography.rar - [Fast Download] kbps. ... Sakamoto on AllMusic - 2011Download Ryuichi Sakamoto - Discography (1978-2012) Mp3 or any .... The Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto has released 19 solo studio albums, six live albums, several compilation albums, two EPs, and various singles and .... Download Ryuichi Sakamoto - Discography (1978-2012) Mp3 or any other file from Music. Fennesz & Ryuichi Sakamoto - Flumina [320. Pure Best [192kbps] .... Listen to Ryuichi Sakamoto - Discography (1978-2012) and ninety- six more episodes by Solicall V1.7.7, free! No signup or install needed. Far.. Ryuichi sakamoto 05 rar shared files: Here you can download ryuichi sakamoto 05 rar shared ... Ryuichi Sakamoto - Discography (1978-2012).. Ryuichi Sakamoto (坂本 龍一 Sakamoto Ryūichi?, born January 17, 1952) (Japanese pronunciation: [sakamoto ɽju͍ːitɕi]) is a Japanese musician, activist, ... -

Connecting Time and Timbre Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops Insymbolic and Signal Domainspdfauthor

Connecting Time and Timbre: Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops in Symbolic and Signal Domains Cárthach Ó Nuanáin TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2017 Thesis Director: Dr. Sergi Jordà Music Technology Group Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Dissertation submitted to the Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA Copyright c 2017 by Cárthach Ó Nuanáin Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www.upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. III Do mo mháthair, Marian. V This thesis was conducted carried out at the Music Technology Group (MTG) of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain, from Oct. 2013 to Nov. 2017. It was supervised by Dr. Sergi Jordà and Mr. Perfecto Herrera. Work in several parts of this thesis was carried out in collaboration with the GiantSteps team at the Music Technology Group in UPF as well as other members of the project consortium. Our work has been gratefully supported by the Department of Information and Com- munication Technologies (DTIC) PhD fellowship (2013-17), Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, as part of the GiantSteps project ((FP7-ICT-2013-10 Grant agreement no. 610591). Acknowledgments First and foremost I wish to thank my advisors and mentors Sergi Jordà and Perfecto Herrera. Thanks to Sergi for meeting me in Belfast many moons ago and bringing me to Barcelona. -

ONA Ilpo Väisänen – Various Electronic Devices Billy Roisz

ONA Ilpo Väisänen – various electronic devices Billy Roisz – electronic devices, bass guitar ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ilpo Väisänen und Billy Roisz wurden im Herbst 2011 von der Linzer Plattform qujOchÖ eingeladen, im Rahmen des Festivals Baumarktmusik gemeinsam aufzutreten. Bei den Konfrontationen 2012 nehmen sie unter dem Duo-Namen ONA diese sehr spannende Zusammenarbeit wieder auf. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ilpo Väisänen (FIN) http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan_Sonic Together with Mika Vainio, Ilpo Väisänen was part of the Finnish duo Pan Sonic, one of the most ground-breaking and innovating projects in contemporary electronic music. In a musical form in which sequencing and recording music using computers is standard, the group was known for recording everything live, straight to DAT (Digital Audio Tape) using home-made and modified synthesizers and effect units. In December 2009 their split was announced. Mika and Ilpo will continue with their own solo projects. Ilpo’s former releases on his own label Kangaroo, a sub-label of Raster-Noton, have clearly shown his personal affinity with dub music. Actually he is also playing some kind of free- form noise with a tendency to drone with Dirk Dresselhaus (Schneider TM) in the duo Angel. --- BIO Ilpo Väisänen: born in Kuopio, Finland, in 1963 studied flute at the conservatory as a young student studied visual arts and -

Discographie

Discographie I. Précurseurs musiques savantes Compilations An Anthology Of Noise & Electronic Music, Vol. 1-5 (Sub Rosa, 2000-2007) Le bruit dans la musique 1900-1950 Compilations Dada et la musique (Centre Georges Pompidou/A&T, 2005) Futurism & Dada Reviewed 1912-1959, (Sub rosa, 1995) Musica Futurista : The Art Of Noise (LTM, 2005) George Antheil, Ballet mécanique, dirigé par Daniel Spalding (Naxos, 2001) Belà Bartók, Le mandarin merveilleux, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1997) John Cage, Sonatas And Interludes For Prepared Piano, interprété par Boris Berman (Naxos, 1999) John Cage, Imaginary Landscapes, dirigé par Jan Williams (Hat Hut, 1995) Henry Cowell, New Music : Piano Compositions By Henry Cowell, interprété par Sorrel Hays, Joseph Kubera, Sarah Cahill (New Albion Records, 1999) Charles Ives, Symphony n°2 etc., dirigé par Léonard Bernstein (Deutsche Grammophon, 1990) Erik Satie, Parade, dirigé par Manuel Rosenthal (Ades, 2007) Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot lunaire, Lied der Waldtaube, Erwartung dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Sony, 1993) Edgard Varese, The Complete Works, dirigé par Riccardo Chailly (Decca, 1998) Musique et timbre, 1950 à nos jours Luciano Berio, Differences, Sequenzas III & VII, Due pezzi, Chamber Music (Lilith, 2007) György Ligeti, Requiem, Aventures, Nouvelles Aventures (Wergo, 1985) György Ligeti, Chamber Concerto, Ramifications, String Quartet n°2, Aventures, Lux aeterna, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1983) Tristan Murail, Gondwana, Désintégrations, Time and Again (Disques Montaigne, 2003) Giacinto Scelsi, The Orchestral Works 2 (Mode, 2006) Krzysztof Penderecki, Anaklasis, Threnody, etc., dirigé par Wanda Wilkomirska (EMI, 1994) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Aus den sieben Tagen (Harmonia Mundi, 1988) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Stimmung (Hyperion, 1986) Iannis Xenakis, Orchestral Works, Vol. -

Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, the Haters, Hanatarash, the Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese…

As Loud as Possible As Loud as Possible Concert de Hanatarash, Toritsu Kasei Loft, Tokyo, 1985 (Photos : Gin Satoh) Concert de Hanatarash, Toritsu Kasei Loft, Tokyo, 1985 (Photos : Gin Satoh) Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, The Haters, Hanatarash, The Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese… Un parcours parmi les grandes figures du harsh noise, au sein de l’internationale du bruit sale de ses origines à nos jours. AS LOUD AS 48 POSSi- 49 bLe. Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, The Haters, Hanatarash, The Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese… A tour among the major figures in harsh noise, within dirty Noise International—from its inception to the present day. Fenêtre ouverte. Le bruit, c’est ce son fronde, indompta- juste une main pour sculpter, une intention pour guider, Mais comment la musique a-t-elle osé muter en ça ? ble, discordant, une puanteur dans l’oreille, comme l’a écrit à peine une idée pour le conceptualiser. Il n’est pas une Objectivement, si on regarde la tête du harsh noise, son Ambrose Bierce dans son Devil’s Dictionary, ce que tout musique bruyante mais une musique-bruit taillée, pas un nom, il faut tout de même se pencher un peu en arrière, le oppose et tout interdit à la musique. Le bruit sévère, le bruit genre, encore moins un mélange, car s’il est né d’amonts XXe siècle brouhaha, pour comprendre cette « birth-death dur, le harsh noise, c’est, pire encore, le chaos volontaire, la lisibles dans l’histoire de la musique, dans l’histoire du XXe experience », si l’on m’autorise à citer le titre d’un disque de crasse en liberté, même pas la musique de son-bruits rêvée siècle, il n’a dans sa pratique et sa nature d’autre horizon Whitehouse, le premier de surcroît. -

A Cross-Genre Analysis of the (Ec)Static Music

Proceedings of the Electroacoustic Music Studies Network Conference The Art of Electroacoustic Music, Sheffield, June 2015 www.ems-network.org A cross-genre analysis of the (ec)static music Riccardo Wanke Centre of Musical Sociology and Aesthetic Study – CESEM, University ‘Nova’ of Lisbon Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Av. de Berna, 26 C, 1069-061 Lisbon, Portugal [email protected] Abstract This paper looks over a selection of pieces belonging to distant genres of today’s music, in order to identify common practices to approach sound. Through audio, spectral and score analyses, this study examines essential musical elements (e.g. pulse, spectral properties, dynamic contrast, spatial arrangements) their characteristics and effects. This method has been applied to post-spectralist and minimalist compositions (e.g. Georg Friedrich Haas, Bernhard Lang, R. Nova, Giovanni Verrando), as well as glitch, electronic and basic-channel style pieces (Pan Sonic, Ryoji Ikeda, Raime). The analysis reveals nine musical attributes that are common within the selection of pieces. These attributes indicate parallels, similar perspectives and a common affinity among different genres. The study contributes essentially by minimising artistic distances and establishing shared musical conceptions. Introduction During last century, various currents of experimental music progressively moved toward a more explicit interest to sound and its characteristics: some scholars refer about a timbre’s evolution to the exploration of sound (Bériachvili, 2008; Solomos, 2013). Starting from the mid-twentieth century, several musical elements (e.g. non-teleological perspectives, the fusion of electronic/acoustic/concrete sounds, the extended use of sound spectra) were simultaneously developed across distant genres of music.