Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Information Presented Here Is As of 10/24/2012. ARABIC STUDIES (Div

The information presented here is as of 10/24/2012. ARABIC STUDIES (Div. I, with some exceptions as noted in course descriptions) Coordinator, Associate Professor CHRISTOPHER BOLTON Assistant Professors NAAMAN, VARGAS. Affiliated Faculty: Professors: DARROW, D. EDWARDS, ROUHI. Associate Professors: BERNHARDS- SON, PIEPRZAK. Visiting Assistant Professor: EL-ANWAR. Senior Lecturer: H. EDWARDS. Middle Eastern Studies is a vibrant and growing discipline in the United States and around the world. Students wishing to enter this rich and varied discipline can begin with a major in Arabic Studies at Williams. The major is designed to give students a foundation in the Arabic language and to provide the opportunity for the interdisciplinary and multi-disciplinary study of the Arab, Islamic, and Middle Eastern arenas. The Major in Arabic Studies Students wishing to major in Arabic Studies must complete nine courses, including the following four courses: ARAB 101-102 Elementary Arabic ARAB 201 Intermediate Arabic I ARAB 202 Intermediate Arabic II Students must also take five courses in Arabic and Middle Eastern Studies in affiliated departments. At least two of these courses should be from the arenas of language and the arts (DIV I) and at least two from politics, religion, economics, and history (DIV II). At least two of these courses must be at an advanced level (300 or 400 level). These might include: ARAB 216/COMP 216 Protest Literature: Arab Writing Across Three Continents ARAB 219/COMP 219/AMST 219 Arabs in America: A Survey ARAB 223/COMP 223 -

Cultural Continuity in Modern Iraqi Painting Between 1950- 1980

Vol.14/No.47/May 2017 Received 2016/06/13 Accepted 2016/11/02 Persian translation of this paper entitled: تداوم فرهنگی در نقاشی مدرن عراق بین سال های 1950 و 1980 is also published in this issue of journal. Cultural Continuity in Modern Iraqi Painting between 1950- 1980 Shakiba Sharifian* Mehdi Mohammadzade** Silvia Naef*** Mostafa Mehraeen**** Abstract Since the early years of 1950, which represent the development period of modern Iraqi art, the “return to the roots” movement has been an impartible mainstream in Iraq. The first generation of modern artists like Jewad Salim and Shakir Hassan Al-Said considered “cultural continuity” and the link between “tradition and modernity” and “inspiration from heritage1” as the main essence of their artistic creation and bequeathed this approach to their next generation. Having analyzed and described a selection of artworks of modern Iraqi artists, this paper discusses the evolution of modern Iraqi art, and aims to determine cultural and artistic continuity in modern paintings of Iraq. It also seeks to answer the questions that investigate the socio-cultural factors that underlie the formation of art and establish a link between traditional and modern ideas and lead to continuity in tradition. Therefore, the research hypothesis is put to scrutiny on the basis of Robert wuthnow’s theory. According to Wuthnow, although configuration and the objective production of this movement is rooted in the “mobilization of resources”, the artistic content and approach of the painting movement (i.e. the continuation of the tradition along with addressing modern ideas) is influenced by factors such as “social Horizon”, “existing discursive context” and “cultural capital” of the painters. -

Defamiliarization in the Poetry of 'Abd Al-Wahh�B Al-Bay�T� and T

DEFAMILIARIZATION IN THE POETRY OF 'ABD AL-WAHH�B AL-BAY�T� AND T. S. ELIOT: A COMPARATIVE STUDY The recoil of 'Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati (1926-1999) from Romanticism with the publication of Abdriq Muhashshamah (Broken Pitchers, 1954),' sig- nalled a shift in his poetic style and subject matter. Al-Bayati's poetry turned increasingly oblique while it became involved in Pan-Arab socio- political affairs. His experimentation with poetic language and devices, how- ever, only matured with the publication of Alladhi Ya'ti wa /a Ya'ti (He Who Comes and Does Not Come, The outstanding characteristic of al-Bayati's poetry since Broken Pitchers became a progress towards achiev- ing defamiliarization. The term defamiliarization, which was coined by Victor Shklovsky, denotes the use of language and poetic devices that ren- der a poem a complex and an ambigious work of art because the "technique of art is to make objects 'unfamiliar The transition in al-Bayati's poetry occurred, in fact, as the result of the reception of the work of T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) in the Arab World through its translations, which, according to Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, had commenced in the 1940s.4 Eliot's free verse initiated the formation of the new literary movement of the so-called New Poets, which included Ndzik al-Mala'ikah (b. 1926), Badr Shakir al-Sayyab (1926-1964), and al-Bayati himself, who became the pioneers of free verse in the early 1950s.5 In this respect, Salma A brief presentation on this paper's central concern and methodology was given in the First International Conference of the Association of Professors of English and Translation at Arab Universities, held in Amman, Jordan, August 28-30, 2000. -

Chronicles of Disappearance: the Novel of Investigation in the Arab World, 1975-1985

Chronicles of Disappearance: The Novel of Investigation in the Arab World, 1975-1985 By Emily Lucille Drumsta A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Margaret Larkin, Chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Karl Britto Professor Stefania Pandolfo Summer 2016 © 2016 Emily Lucille Drumsta All Rights Reserved Abstract Chronicles of Disappearance: The Novel of Investigation in the Arab World, 1975-1985 by Emily Lucille Drumsta Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Margaret Larkin, Chair This dissertation identifies investigation as an ironic narrative practice through which Arab authors from a range of national contexts interrogate certain forms of political language, contest the premises of historiography, and reconsider the figure of the author during periods of historical upheaval. Most critical accounts of twentieth-century Arabic narrative identify the late 1960s as a crucial turning point for modernist experimentation, pointing particularly to how the defeat of the Arab Forces in the 1967 June War generated a self-questioning “new sensibility” in Arabic fiction. Yet few have articulated how these intellectual, spiritual, and political transformations manifested themselves on the more concrete level of literary form. I argue that the investigative plot allows the authors I consider to distance themselves from the political and literary languages they depict as rife with “pulverized,” “meaningless,” “worn out,” or “featureless” words. Faced with the task of distilling meaning from losses both physical and metaphysical, occasioned by the traumas of war, exile, colonialism, and state violence, these authors use investigation to piece together new narrative forms from the debris of poetry, the tradition’s privileged mode of historical reckoning. -

Modernism and After: Modern Arabic Literary Theory from Literary Criticism to Cultural Critique

1 Modernism and After: Modern Arabic Literary Theory from Literary Criticism to Cultural Critique Khaldoun Al-Shamaa Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies 2006 ProQuest Number: 10672985 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672985 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 DECLARATION I Confirm that the work presented in the thesis is mine alone. Khaldoun Al-Shamaa 3 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to provide the interested reader with a critical account of far-reaching changes in modem Arabic literary theory, approximately since the 1970s, in the light of an ascending paradigm in motion , and of the tendency by subsequent critics and commentators to view litefary criticism in terms of self-a elaborating category morphing into cultural critique. The first part focuses on interdisciplinary problems confronting Arab critics in their attempt “to modernize but not to westernize”, and also provides a comparative treatment of the terms, concepts and definitions used in the context of an ever-growing Arabic literary canon, along with consideration of how these relate to European modernist thought and of the controversies surrounding them among Arab critics. -

Resistance Literature and Occupied Palestine in Cold War Beirut

Journal of Palestine Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpal20 Resistance Literature and Occupied Palestine in Cold War Beirut Elizabeth M. Holt To cite this article: Elizabeth M. Holt (2021): Resistance Literature and Occupied Palestine in Cold War Beirut, Journal of Palestine Studies To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0377919X.2020.1855933 Published online: 22 Jan 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpal20 JOURNAL OF PALESTINE STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/0377919X.2020.1855933 Resistance Literature and Occupied Palestine in Cold War Beirut Elizabeth M. Holt ABSTRACT KEYWORDS For the last decade of his life, the Palestinian intellectual, author, and editor Cold War; Palestine; Ghassan Kanafani (d. 1972) was deeply immersed in theorizing, lecturing, Ghassan Kanafani; Arthur and publishing on Palestinian resistance literature from Beirut. A refugee Koestler; resistance of the 1948 war, Kanafani presented his theory of resistance literature and literature; Afro-Asian writers; Beirut; Arabic novel the notion of “cultural siege” at the March 1967 Beirut conference of the Soviet-funded Afro-Asian Writers Association (AAWA). Articulated in resis- tance to Zionist propaganda literature and in solidarity with Marxist- Leninist revolutionary struggles in the Third World, Kanafani was inspired by Maxim Gorky, William Faulkner, and Mao Zedong alike. In books, essays, and lectures, Kanafani argued that Zionist propaganda literature served as a “weapon” in the war against Palestine, returning repeatedly to Arthur Koestler’s 1946 Thieves in the Night. -

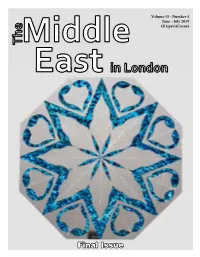

Final Issue Volume 15 - Number 4 June – July 2019 £8 (Special Issue)

Volume 15 - Number 4 June – July 2019 £8 (special issue) Final Issue Volume 15 - Number 4 June – July 2019 £8 (special issue) Final Issue Monir Farmanfarmaian, Untitled (Octagon), 2016. Mirror and reverse glass painting on About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) plexiglass, 32 cm in diameter. Courtesy of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian family and The The London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide Third Line, Dubai teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defined and helps to create links between Volume 15 – Number 4 individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. June–July 2019 With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. The LMEI also Editorial Board has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Dr Orkideh Behrouzan SOAS it takes primary responsibility. It seeks support for the LMEI generally and for specific components of its Dr Hadi Enayat programme of activities. AKU LMEI is a Registered Charity in the UK wholly owned by SOAS, University of London (Charity Ms Narguess Farzad SOAS Registration Number: 1103017). Mrs Nevsal Hughes Association of European Journalists Professor George Joffé Mission Statement: Cambridge University Dr Ceyda Karamursel SOAS The aim of the LMEI, through education and research, is to promote knowledge of all aspects of the Middle Mrs Margaret Obank East including its complexities, problems, achievements and assets, both among the general public and with Banipal Publishing those who have a special interest in the region. -

Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction Mona Nabeel Malkawi University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 1-2016 Twice Heard, Paradoxically (Un)seen: Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction Mona Nabeel Malkawi University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malkawi, Mona Nabeel, "Twice Heard, Paradoxically (Un)seen: Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1769. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1769 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Twice Heard, Paradoxically (Un)seen: Walking the Tightrope of Invisibility in Palestinian Translated Fiction A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Mona Nabeel Malkawi Yarmouk University Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature, 2006 Yarmouk University Master of Arts in Translation, 2009 December 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council: ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Professor John DuVal Dissertation Director ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Professor Adnan Haydar Professor Charles Adams Committee Member Committee Member ©2016 by Mona Nabeel Malkawi All Rights Reserved Abstract This study examines the translators’ invisibility in postcolonial translated Palestinian fiction. On one hand, this analysis revolves around the ethical stance of translators towards authors in a postcolonial theoretical framework. -

Cbcs Syllabus

CBCS SYLLABUS For Programmes: 1- M.A. Arabic 2- M.A. Arab Culture and Civilization 3- M.A. Modern Arabic Department of Arabic University of Lucknow (All Three Programmes shall be of 96 Credits with Four Semesters) Courses offered with effect from Session 2020-2021 Programme M.A. Arabic Programme’s Specific Outcome (PSO) ( 1st & 2nd Semesters ) Introduction: ** This programme has been designed to introduce the students to the distinct and varied aspects of Arabic literature and their development from Ancient period up to Modern Age. ** Arabic Prose and Poetry: This course will familiarize the students with main Arabic literary genres, the nature and specific style of Arabic Prose and poetry and their historical developments. ** The course also addresses the cultural context of their Arabic literature. ** It also attempts to acquaint them with major authors and their works in divergent regions of the modern Arab World and to articulate orally and in writing the major critical issues relevant to Arabic literature and literary studies. ** This course also introduces the students important works of major Arab poets of the Medieval and modern centuries. In contrast to the totality of Arabic poetry since medieval period, Modern Arabic poetry is the best described one in a field of on-going experimentation with a new set of topics, choices, concerns, inspirations and forms. ** The Novel and Prose on Various social and cultural issues have been the most important genres of Arabic Literature; they have enriched the Arabic Literature heavily in Medieval as well as Modern periods. This genre, especially the Arabic Novel, has received the greatest attention, and today it has made its presence felt across the world. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Chronicles of Disappearance: The Novel of Investigation in the Arab World, 1975-1985 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6tf2596b Author Drumsta, Emily Lucille Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Chronicles of Disappearance: The Novel of Investigation in the Arab World, 1975-1985 By Emily Lucille Drumsta A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Margaret Larkin, Chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Karl Britto Professor Stefania Pandolfo Summer 2016 © 2016 Emily Lucille Drumsta All Rights Reserved Abstract Chronicles of Disappearance: The Novel of Investigation in the Arab World, 1975-1985 by Emily Lucille Drumsta Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Margaret Larkin, Chair This dissertation identifies investigation as an ironic narrative practice through which Arab authors from a range of national contexts interrogate certain forms of political language, contest the premises of historiography, and reconsider the figure of the author during periods of historical upheaval. Most critical accounts of twentieth-century Arabic narrative identify the late 1960s as a crucial turning point for modernist experimentation, pointing particularly to how the defeat of the Arab Forces in the 1967 June War generated a self-questioning “new sensibility” in Arabic fiction. Yet few have articulated how these intellectual, spiritual, and political transformations manifested themselves on the more concrete level of literary form. -

The Bronze Sculptures As a Model

COMPETITIVE STRATEGY MODEL AND ITS IMPACT ON MICRO BUSINESS UNITOF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT BANKSIN JAWAPJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) Figure Features in Sadiq Rabee's Sculptures: the Bronze Sculptures as a Model Mustafa Thamer Shafi1, Aqeel Husseln Jaslm2 1College of Fine Arts-University of Babylon 2College of Fine Arts-University of Babylon Mustafa Thamer Shafi, Aqeel Husseln JaslmFigure Features in Sadiq Rabee's Sculptures: the Bronze Sculptures as a Model-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7), 3722-3732. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Micro Business Unit, Competitive Strategy, Performance ABSTRACT The current research included the features of the form in the sculptures of Sadiq Rabee, "Bronze sculptures as a model", four chapters about me, the first of which is the general framework of the research, while the second chapter in the current study included the theoretical framework that contained two knowledge topics, the first of which was addressed: an introduction to the meaning of the form while the second topic included two axes The first axis included the figure in contemporary Iraqi sculpture, and the second axis included the sculptor Sadiq. At the end of the third chapter, the researcher mentioned the indicators that emerged from this chapter. As for the research procedures, in which the researcher identified his research community as (20) sculptural works from which the researcher chose in an intentional manner the samples of his research that were identified as (3) sculptural works. The descriptive and analytical approach is adopted in its analysis, and concluded by analyzing samples, as the sculptor in Mengizah relied on a method that tended to modernity in shaping because of its effect through his studies in Italy and his acquaintance with the methods of artistic formation related to the propositions of modernity in the completion of sculptural works as in most models. -

Jerusalem Of

1 Preface Jerusalem has always held a certain mystique for visitors, be they pilgrims, travel- ers, or would-be conquerors. The Arab people and motifs that have been present in the city since its founding have never failed to fascinate and mystify. Jerusalem was the site of Europe’s first interaction with legendary Arab figures like Omar Ibn Al-Khatib and Salah Eddin;1 the reverence garnered by such leaders invari- ably led to a higher profile in the rest of the world for Arabs as a whole. As much as Jerusalem has given to those who have visited her, outsiders have, in turn, left their own cultural imprints on the city. For many Arab Jerusalemites, it has been through the classroom that they have felt the impact of external culture. Artists like Sophie Halaby, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, and Nahil Bishara studied in the West at institutions in Italy, France, and the United Kingdom. Prominent intellectuals associated with Jerusalem and Palestine - Rashid Khalidi and Edward Said for example - have ties to the world’s top universities. The issue of Jerusalem is normally portrayed in a political-religious context, but the weight of historical and cultural factors cannot be overstated. The conflict extends into every facet of society, and in this sense the battle for Jerusalem has been markedly one-sided. This siege on Arabs and Arab culture is seen in every field, stretching from education - where students and teachers face a lack of classrooms and adequate materials - to architecture - where building restrictions and demolitions are the norm – and cultural events – which are disrupted or banned altogether.