New Alternatives for Minimally Invasive Management of Uroliths: Nephroliths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partial Nephrectomy for Renal Cancer: Part I

REVIEW ARTICLE Partial nephrectomy for renal cancer: Part I BJUIBJU INTERNATIONAL Paul Russo Department of Surgery, Urology Service, and Weill Medical College, Cornell University, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA INTRODUCTION The Problem of Kidney Cancer Kidney Cancer Is The Third Most Common Genitourinary Tumour With 57 760 New Cases And 12 980 Deaths Expected In 2009 [1]. There Are Currently Two Distinct Groups Of Patients With Kidney Cancer. The First Consists Of The Symptomatic, Large, Locally Advanced Tumours Often Presenting With Regional Adenopathy, Adrenal Invasion, And Extension Into The Renal Vein Or Inferior Vena Cava. Despite Radical Nephrectomy (Rn) In Conjunction With Regional Lymphadenectomy And Adrenalectomy, Progression To Distant Metastasis And Death From Disease Occurs In ≈30% Of These Patients. For Patients Presenting With Isolated Metastatic Disease, Metastasectomy In Carefully Selected Patients Has Been Associated With Long-term Survival [2]. For Patients With Diffuse Metastatic Disease And An Acceptable Performance Status, Cytoreductive Nephrectomy Might Add Several Additional Months Of Survival, As Opposed To Cytokine Therapy Alone, And Prepare Patients For Integrated Treatment, Now In Neoadjuvant And Adjuvant Clinical Trials, With The New Multitargeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (Sunitinib, Sorafenib) And Mtor Inhibitors (Temsirolimus, Everolimus) [3,4]. The second groups of patients with kidney overall survival. The explanation for this cancer are those with small renal tumours observation is not clear and could indicate (median tumour size <4 cm, T1a), often that aggressive surgical treatment of small incidentally discovered in asymptomatic renal masses in patients not in imminent patients during danger did not counterbalance a population imaging for of patients with increasingly virulent larger nonspecific abdominal tumours. -

Urogenital System Surgery Urogenital System Anatomy

UROGENITAL SYSTEM SURGERY UROGENITAL SYSTEM ANATOMY Kidneys and Ureters Urinary Bladder Urethra Genital Organs Male Genital Organs Female KIDNEY and URETHERS The kidneys lie in the retroperitoneal space lateral to the aorta and the caudal vena cava. They have a fibrous capsule and are held in position by subperitoneal connective tissue. The renal pelvis is the funnel shaped structure that receives urine and directs it into the ureter. Generally, five or six diverticula curve outward from the renal pelvis. The renal artery normally bifurcates into dorsal and ventral branches; however, variations in the renal arteries and veins are common. The ureter begins at the renal pelvis and enters the dorsal surface of the bladder obliquely by means of two slit like orifices. The blood supply to the ureter is provided from the cranial ureteral artery (from the renal artery) and the caudal ureteral artery (from the prostatic or vaginal artery). Urinary bladder and urethra The bladder is divided into the trigone, which connects it to the urethra, and the body. The urethra in male dogs and cats is divided into prostatic, membranous (pelvic), and penile portions. Surgery of Kidney and Urethers Nephrectomy is excision of the kidney; nephrotomy is a surgical incision into the kidney. Pyelolithotomy is an incision into the renal pelvis and proximal ureter; a ureterotomy is an incision into the ureter; both are generally used to remove calculi. Neoureterostomy is a surgical procedure performed to correct intramural ectopic ureters; ureteroneocystostomy involves implantation of a resected ureter into the bladder. Nephrotomy to obtain tissue samples or to gain access to the renal pelvis for removal of nephroliths or other obstructive lesions. -

Methods of Urolith Removal

3 CE CE Article CREDITS Methods of Urolith Removal Cathy Langston, DVM, DACVIM (Small Animal Internal Medicine) Kelly Gisselman, DVM Douglas Palma, DVM John McCue, DVM Animal Medical Center New York, New York Abstract: Multiple techniques exist to remove uroliths from each section of the urinary tract. Minimally invasive methods for removing lower urinary tract stones include voiding urohydropropulsion, retrograde urohydropropulsion followed by dissolution or removal, catheter retrieval, cystoscopic removal, and cystoscopy-assisted laser lithotripsy and surgery. Laparoscopic cysto- tomy is less invasive than surgical cystotomy. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy can be used for nephroliths and ureteroliths. Nephrotomy, pyelotomy, or urethrotomy may be recommended in certain situations. This article discusses each technique and gives guidance for selecting the most appropriate technique for an individual patient. ew, minimally invasive techniques for removing preventive measures.7 Surgical removal of partial or com- uroliths have been developed or have become more pletely obstructing ureteroliths that do not pass within 24 Nreadily available in veterinary medicine. TABLE hours may be prudent.8 A staged approach to surgery can be 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each considered if uroliths are found at multiple sites in the upper method, the number and type of uroliths for which each is urinary tract. The reversibility of renal dysfunction depends appropriate, and necessary equipment for each. on completeness and duration -

Approaches to Pyelolithotomy

Vet Times The website for the veterinary profession https://www.vettimes.co.uk APPROACHES TO PYELOLITHOTOMY Author : Nitzan Kroter Categories : Vets Date : February 14, 2011 Nitzan Kroter discusses this procedure in reference to a case involving the removal of calcium phosphate renoliths in a cat with only one functional kidney Summary A 12-year-old cat was presented for chronic weight loss. Clinical evaluation and investigation revealed an atrophied left kidney with nephroliths and an enlarged right kidney containing multiple renal calculi. Bilateral calcium phosphate renal calculi were diagnosed. This report describes pyelolithotomy in a cat. Pyelolithotomy was performed to avoid damage to the renal parenchyma, which could occur during a nephrotomy, and, therefore, minimise further damage to an already compromised kidney. Before performing surgery, consideration of the patient’s renal function is important to obtain optimal results. Maintaining normal urine production in the pre-operative and postoperative period is important in all cases. Pyelolithotomy in the dog is covered and described in the literature; the author is unaware of a detailed description of pyelolithotomy in a cat. Key words kidney, pyelolithotomy, urine 1 / 7 A NEUTERED domestic shorthaired male feline presented with a complaint of marked weight loss over the preceding few months. It weighed 2.6kg. When recorded two-and-ahalf years previously, its weight had been 5.5kg. The owner reported recent increased activity, the cat was more talkative and attention seeking, and had a normal appetite. There was no history of polydipsia or polyuria, and there had been no vomiting or diarrhoea. Clinical examination and investigation The patient had a body condition score of 2/4 and an unkempt coat, but it was responsive and alert. -

International Journal of Current Advan Urnal of Current Advanced Research

International Journal of Current Advanced Research ISSN: O: 2319-6475, ISSN: P: 2319-6505, Impact Factor: 6.614 Available Online at www.journalijcar.org Volume 8; Issue 03 (A); March 2019; Page No. 17644-17646 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24327/ijcar.2019.17646-3354 Research Article RETAINED TUBES - A NIGHTMARE IN UROLOGY Srinivasan T and Senthil Kumar T Department of Urology, SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Kattankulathur, Kancheepuram District, Tamilnadu, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Patients undergoing urological procedures fail to undergo tube removal at appropriate time Received 15th December, 2019 and they present themselves after many years with Retained tubes. These Retained tubes Received in revised form 7th continue to remain one of the biggest problems in the urology care at the present outset January, 2019 inspite of all the effects taken to prevent it. In our medical college we retrospectively Accepted 13th February, 2019 reviewed our institute database from june 2013 to dec 2018 for retained tubes like ureteral Published online 28th March, 2019 stents, urethral catheters, suprapubic catheter and nephrostomy tubes. Total of 18 patients presented with retained tubes .11 were with retained ureteral stents ,5 were with urethral Key words: catheters,1 with retained suprapubic catheter and 1 with nephrotomy tube. 5 retained ureteral stents patients were managed by simple ureterorenoscopy and stent removal.3 Vesicolithotripsy,Nephrectomy,ESWL. patients required ESWL and URS with stent removal,3 patients needed PCNL with ESWL. Retained urethral catheters were managed with cystolithotripsy and tube removal .Patient with retained suprapubic catheter was managed with open vesicolithotomy . -

The Progress of Cystoscopy in the Last Three Years

The Progress of Cystoscopy- in the Last Three Years. BY WILLY MEYER, M. D., MBimwwiHi.n ■■ Attending Surgeon to tne German aDd New York Skin and Cancer Hospitals. RKPSHtTKB FROM €TJ}e Neto Yorfe ir8eDtcsl journal 30 far January , 1892. Reprinted, from, the New York Medical Journal for January 30, 1892. THE PROGRESS OF CYSTOSCOPY IN THE LAST THREE YEARS.* By WILLY MEYER, M. D., ATTENDING TO THE GERMAN AND NEW YORK SKIN AND CANCER HOSPITALS. Three years ago Dr. Max Nitze, of Berlin, the inventor of the cystoscope, in his well-known essay, Contribution to Endoscopy of the Male Bladder,f stated that we could now, with the help of the cystoscope in its handy and improved shape, establish a strict differential diagnosis between the diseases of the bladder. He further said : “ Having seen with the cystoscope that the bladder is healthy, and that the morbid process therefore involves the upper urinary pas- sages, most probably the kidneys, it is tempting to put the question whether we shall be able to prove with the cysto- scope which kidney or which pelvis of the kidney is dis- eased. Either we could attempt to push a thin catheter under the guide of our eyes into the orifice of the ureters, to draw the urine directly from each kidney separately, or we might be able to observe with the cystoscope out of * Read in part before the Medical Society of the State of New York at its eighty-fifth annual meeting, Albany, February 3, 1891. f Y. Langenbeck’s Arcliivf. Min. Chirurgie, vol. -

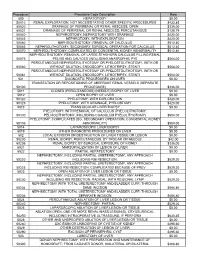

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Whatts New in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Urinary

Artigo Original O QUE HÁ DE NOVO NO DIAGNÓSTIco E TRATAMENTO DA LITÍASE URINÁRIA? EDUARDO MAZZUccHI1*, MIGUEL SroUGI2 Trabalho realizado na Divisão de Clínica Urológica do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, S.Paulo, SP RESUMO OBJETIVO. Atualizar aspectos do diagnóstico e do tratamento da litíase urinária. MÉTODOS. Uma revisão dos principais artigos publicados sobre o tema em revistas indexadas no “Medline” entre 1979 e 2009. RESULTADOS. A ocorrência de cálculos é maior em pacientes com IMC > 30. A TC sem contraste promove o diagnóstico correto em até 98% dos casos. O uso de bloqueadores alfa-adrenérgicos aumenta a eliminação de cálculos ureterais menores que 8 mm em 29%. O índice de pacientes livres de cálculo após LEOC varia entre 35% e 91%, conforme seu tamanho e localização. Cálculos renais maiores que 2 cm são eliminados pela NLPC entre 60% e 100% dos casos. Cálculos de ureter distal são tratados com sucesso em até 94% dos casos pela ureteroscopia semirrígida contra 74% da LEOC. Já para cálculos de ureter superior as taxas de sucesso situam-se entre 77% e 91% para ureteroscopia e 41% e 82% para a LEOC. CONCLUSÃO. A associação da calculose urinária com obesidade e Diabetes mellitus está bem estabelecida. A TC sem contraste é atualmente o padrão-ouro no diagnóstico da litíase urinária. A LEOC é o método de eleição em nosso meio para tratamento de cálculos renais menores que 2 cm e com densidade tomográfica < 1000 UH, exceto os do cálice inferior, onde o limite ideal de tratamento é 1 cm. -

Coding Companion for Urology/Nephrology a Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to Coding and Reimbursement

Coding Companion for Urology/Nephrology A comprehensive illustrated guide to coding and reimbursement 2015 Contents Getting Started with Coding Companion .............................i Scrotum ..........................................................................328 Integumentary.....................................................................1 Vas Deferens....................................................................333 Arteries and Veins ..............................................................15 Spermatic Cord ...............................................................338 Lymph Nodes ....................................................................30 Seminal Vesicles...............................................................342 Abdomen ..........................................................................37 Prostate ...........................................................................345 Kidney ...............................................................................59 Reproductive ...................................................................359 Ureter ..............................................................................116 Intersex Surgery ..............................................................360 Bladder............................................................................153 Vagina .............................................................................361 Urethra ............................................................................226 Medicine -

Treatment of Recurrent Renal Transplant Lithiasis: Analysis of Our Experience and Review of the Relevant Literature

Treatment of recurrent renal transplant lithiasis: analysis of our experience and review of the relevant literature Xiaohang Li First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Baifeng Li First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Yiman Meng First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Lei Yang First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Gang Wu First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Hongwei Jing First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Jianbin Bi First Aliated Hospital of China Medical University Jialin Zhang ( [email protected] ) First Aliated hospital of China Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0929-8328 Research article Keywords: Renal transplant lithiasis, Transplanted kidney stone, Calculus, Recurrence, Treatment Posted Date: November 27th, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.17873/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract Background:Renal transplant lithiasis is a rather unusual disease, and the recurrence of lithiasis presents a challenging situation. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed medical history of the patient who surferred renal transplant lithiasis for two times, reviewed the relevant literature, and summarized the characteristics of this disease. Results: We retrieved 29 relevant studies with an incidence of 0.34% to 3.26% for renal transplant lithiasis.The summarized incidence is 0.52%, and the recurrent rate is 0.082%. The mean interval after transplantation is 33.43±56.70 m.Most of the patients(28.90%) are asymptomatic.The management included percutaneous nephrolithotripsy(PCNL,22.10%),ureteroscope(URS,22.65%),extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy(ESWL,18.60%) and conservative treatment(17.13%).In our case the patient suffered from renal transplant lithiasis at 6 years post transplantation, and the lithiasis recurred 16 months later. -

2020 Compilation of Inpatient Only Lists by Specialty

2020 Compilation of Inpatient Only Lists by Specialty Designed for CPT Searching 2020 Bariatric Surgery: Is the Surgery Medicare Inpatient Only or not? Disclaimer: This is not the CMS Inpatient Only Procedure List (Annual OPPS Addendum E). No guarantee can be made of the accuracy of this information which was compiled from public sources. CPT Codes are property of the AMA and are made available to the public only for non-commercial usage. Gastric Bypass or Partial Gastrectomy Procedures Inpatient Only Procedure Not an Inpatient Only Procedure 43644 Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive 43659 Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, stomach procedure; with gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy (roux limb 150 cm or less) 43645 Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; with gastric bypass and small intestine reconstruction to limit absorption 43775 Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; longitudinal gastrectomy (ie, sleeve gastrectomy) 43843 Gastric restrictive procedure, without gastric bypass, for morbid obesity; other than vertical- banded gastroplasty 43845 Gastric restrictive procedure with partial gastrectomy, pylorus-preserving duodenoileostomy and ileoileostomy (50 to 100 cm common channel) to limit absorption (biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch) 43846 Gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity; with short limb (150 cm or less) Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy 43847 Gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity; with small intestine reconstruction -

Urology/ Nephrology a Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to Coding and Reimbursement

CODING COMPANION Urology/ Nephrology A comprehensive illustrated guide to coding and reimbursement Sample 2021 optum360coding.com Contents Getting Started with Coding Companion..................................i Penis................................................................................................... 327 CPT Codes ...............................................................................................i Testis ................................................................................................. .363 ICD-10-CM...............................................................................................i Epididymis........................................................................................ 378 Detailed Code Information.................................................................i Tunica Vaginalis .............................................................................. 385 Appendix Codes and Descriptions....................................................i Scrotum............................................................................................. 388 CCI Edit Updates....................................................................................i Vas Deferens .................................................................................... 393 Index.........................................................................................................i Spermatic Cord................................................................................ 397 General Guidelines