Valadondramathel027482mbp.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 355 H-France Review Vol. 9 (June 2009), No. 86 Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire

H-France Review Volume 9 (2009) Page 355 H-France Review Vol. 9 (June 2009), No. 86 Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory (Ahmanson-Murphy Fine Arts Books). University of California Press: Berkeley, 2008. 334 pp. + illustrations. $49.95 (hb). ISBN 052-0243- 617. Review by John Finlay, Independent Scholar. Peter Read’s Picasso et Apollinaire: Métamorphoses de la memoire 1905/1973 was first published in France in 1995 and is now translated into English, revised, updated and developed incorporating the author’s most recent publications on both Picasso and Apollinaire. Picasso & Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory also uses indispensable material drawn from pioneering studies on Picasso’s sculptures, sketchbooks and recent publications by eminent scholars such as Elizabeth Cowling, Anne Baldassari, Michael Fitzgerald, Christina Lichtenstern, William Rubin, John Richardson and Werner Spies as well as a number of other seminal texts for both art historian and student.[1] Although much of Apollinaire’s poetic and literary work has now been published in French it remains largely untranslated, and Read’s scholarly deciphering using the original texts is astonishing, daring and enlightening to the Picasso scholar and reader of the French language.[2] Divided into three parts and progressing chronologically through Picasso’s art and friendship with Apollinaire, the first section astutely analyses the early years from first encounters, Picasso’s portraits of Apollinaire, shared literary and artistic interests, the birth of Cubism, the poet’s writings on the artist, sketches, poems and “primitive art,” World War I, through to the final months before Apollinaire’s death from influenza on 9 November 1918. -

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY of P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS Iwasttr of Fint Girt

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS DISSERTATION SU8(N4ITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIfJIMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iWasttr of fint girt (M. F. A.) SABIRA SULTANA '^tj^^^ Under the supervision of 0\AeM'TCVXIIK. Prof. ASifl^ M. RIZVI Dr. (Mrs) SIRTAJ RlZVl S'foervisor Co-Supei visor DEPARTMENT OF FINE ART ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 Z>J 'Z^ i^^ DS28S5 dedicated to- (H^ 'Parnate ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY CHAIRMAN DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.), INDIA Dated TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Sabera Sultana of Master of Fine Art (M.F.A.) has completed her dissertation entitled "AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P.A. RENOIR'S PAINTINGS" under the supervision of Prof. Ashfaq M. Rizvi and co-supervision of Dr. (Mrs.) Sirtaj Rizvi. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work is based on the investigations made, data collected and analysed by her and it has- not been submitted in any other university or Institution for any degree. Mrs. SEEMA JAVED Chairperson m4^ &(Mi/H>e& of Ins^tifHUion/, ^^ui'lc/aace' cm^ eri<>ouruae/riefity: A^ teacAer^ and Me^^ertHs^^r^ o^tAcsy (/Mser{xUlafi/ ^rof. £^fH]^ariimyrio/ar^ tAo las/y UCM^ accuiemto &e^£lan&. ^Co Aasy a€€n/ kuid e/KHc^ tO' ^^M^^ me/ c/arin^ tA& ^r€^b<ir<itlan/ of tAosy c/c&&erla6iafi/ and Aasy cAecAe<l (Ao contents' aMd^yormM/atlan&^ arf^U/ed at in/ t/ie/surn^. 0A. Sirta^ ^tlzai/ ^o-Su^benn&o^ of tAcs/ dissertation/ Au&^^UM</e^m^o If^fi^^ oft/us dissertation/, ^anv l>eAo/den/ to tAem/ IhotA^Jrom tAe/ dee^ o^nu^ l^eut^. -

Lapin Agile in Winter

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Lapin Agile in Winter Ah, Montmartre, with its provincial corners and its bohemian ways...Iwould be so at ease near you, sitting in my room, composing a motif of white houses or all other things. Utrillo to César Gay from the Villejuif asylum, 19161(p6) AURICE UTRILLO (1883-1955) WAS BORN ON instruction, and he began to demonstrate real talent. Relieved, December 26 in the Montmartre quarter of and considering him cured, his mother took him back to Mont- Paris, France. He began to paint as occupa- martre, thinking that she could return to her own work as an art- tional therapy under the tutelage of his mother ist. Soon Maurice was drinking again and getting into fights, of- to divert him from alcoholism.2 Reluctant at ten returning home beaten and bruised. Mfirst, he gradually began to paint what he saw around him. His As his talent was recognized, rather than serve as a distraction cityscapes (city streets, favorite parts of Montmartre, and churches) from alcohol, his paintings were often exchanged for drinks. Each delighted the man in the street and intrigued the connoisseur. day he would vow to remain sober, yet by day’s end, he would be Although he was surrounded by the founders of modern ab- overcome by a craving for alcohol. He would drink alone and be- stract art, he recreated the city around him by realistically pre- come agitated and threatening. His mother continually rescued senting simplified images of familiar scenes. His work has a cer- him after his bouts of drinking and brought him home, seeking tain calmness and a nostalgic vitality about it, suggesting that there hospital admission as a last resort. -

Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern

Lauren Jimerson exhibition review of Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Citation: Lauren Jimerson, exhibition review of “Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern ,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw. 2020.19.1.14. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Jimerson: Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Grand Palais, Paris October 9, 2019–January 27, 2020 Catalogue: Stéphane Guégan ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: Résolument moderne. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RMN–Grand Palais, 2019. 352 pp.; 350 color illus.; chronology; exhibition checklist; bibliography; index. $48.45 (hardcover) ISBN: 978–2711874033 “Faire vrai et non pas idéal,” wrote the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864– 1901) in a letter to his friend Étienne Devismes in 1881. [1] In reaction to the traditional establishment, constituted especially by the École des Beaux-Arts, the Paris Salon, and the styles and techniques they promulgated, Toulouse-Lautrec cultivated his own approach to painting, while also pioneering new methods in lithography and the art of the poster. He explored popular, even vulgar subject matter, while collaborating with vanguard artists, writers, and stars of Bohemian Paris. Despite his artistic innovations, he remains an enigmatic and somewhat liminal figure in the history of French modern art. -

The Earful Tower's Bucket List: 100 Things to Do in Paris in 2021

The Earful Tower’s Bucket List: 100 things to do in Paris in 2021 1. Galeries Lafayette rooftop 34. Vincennes Human Zoo 68. Le Bar Dix 2. Vanves flea market 35. Georges V hotel 69. Serres d’Auteuil garden 3. Louis Vuitton Foundation 36. Vaux le Vicomte 70. Vie Romantique musuem 4. Grand Palais exhibition 37. Comédie Française 71. Le Meurice Restaurant 5. Sevres Ceramics Museum 38. Rungis market 72. Roland Garross 6. Cruise Canal St Martin 39. Surf in 15eme 73. Arts Décoratifs museum 7. Eat in Eiffel Tower 40. Jardins de Bagatelle 74. Montparnasse Tower 8. Watch PSG game 41. Bees at the Opera 75. Bois de Boulogne biking 9. Black Paris Tour 42. Saint Étienne du Mont 76. Richelieu library 10. Petit Palais Cafe 43. 59 rue de Rivoli. 77. Gravestone Courtyard 11. Lavomatic speakeasy 44. Grange-Batelière river 78. Piscine Molitor 12. L’As du Fallafel 45. Holybelly 19 79. Cafe Flore. 13. Pullman hotel rooftop 46. Musee Marmottan 80. Sainte Chapelle choir 14. Chapel on Rue du Bac 47. Grande Arche 81. Oldest Paris tree 15. Jardin des Plantes 48. 10 Rue Jacob 82. Musée des Arts Forains 16. Arago medallions hunt 49. Grande Chaumière ateliers 83. Vivian Maier exhibit 17. National France Library 50. Moulin de la Galette 84. Chess at Luxembourg 18. Montmartre Cemetery cats 51. Oscar Wilde’s suite 85. André Citroën baloon 19. Bustronome Bus meal 52. Credit Municipal auction 86. Dali museum 20. Walk La Petite Ceinture 53. Seine Musicale 87. Louxor cinema 21. Maxims de Paris 54. Levallois street art 88. -

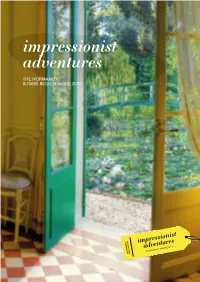

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

André Derain Stoppenbach & Delestre

ANDR É DERAIN ANDRÉ DERAIN STOPPENBACH & DELESTRE 17 Ryder Street St James’s London SW1Y 6PY www.artfrancais.com t. 020 7930 9304 email. [email protected] ANDRÉ DERAIN 1880 – 1954 FROM FAUVISM TO CLASSICISM January 24 – February 21, 2020 WHEN THE FAUVES... SOME MEMORIES BY ANDRÉ DERAIN At the end of July 1895, carrying a drawing prize and the first prize for natural science, I left Chaptal College with no regrets, leaving behind the reputation of a bad student, lazy and disorderly. Having been a brilliant pupil of the Fathers of the Holy Cross, I had never got used to lay education. The teachers, the caretakers, the students all left me with memories which remained more bitter than the worst moments of my military service. The son of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was in my class. His mother, a very modest and retiring lady in black, waited for him at the end of the day. I had another friend in that sinister place, Linaret. We were the favourites of M. Milhaud, the drawing master, who considered each of us as good as the other. We used to mark our classmates’s drawings and stayed behind a few minutes in the drawing class to put away the casts and the easels. This brought us together in a stronger friendship than students normally enjoy at that sort of school. I left Chaptal and went into an establishment which, by hasty and rarely effective methods, prepared students for the great technical colleges. It was an odd class there, a lot of colonials and architects. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Y 2 0 ANDRE MALRAUX: the ANTICOLONIAL and ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University Of

Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Cruz, Richard A., Andre Malraux: The Anticolonial and Antifascist Years. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1996, 281 pp., 175 titles. This dissertation provides an explanation of how Andr6 Malraux, a man of great influence on twentieth century European culture, developed his political ideology, first as an anticolonial social reformer in the 1920s, then as an antifascist militant in the 1930s. Almost all of the previous studies of Malraux have focused on his literary life, and most of them are rife with errors. This dissertation focuses on the facts of his life, rather than on a fanciful recreation from his fiction. The major sources consulted are government documents, such as police reports and dispatches, the newspapers that Malraux founded with Paul Monin, other Indochinese and Parisian newspapers, and Malraux's speeches and interviews. Other sources include the memoirs of Clara Malraux, as well as other memoirs and reminiscences from people who knew Andre Malraux during the 1920s and the 1930s. The dissertation begins with a survey of Malraux's early years, followed by a detailed account of his experiences in Indochina. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Suzanne Preston Blier Picasso’S Demoiselles

Picasso ’s Demoiselles The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece Suzanne PreSton Blier Picasso’s Demoiselles Blier_6pp.indd 1 9/23/19 1:41 PM The UnTold origins of a Modern MasTerpiece Picasso’s Demoiselles sU zanne p res T on Blie r Blier_6pp.indd 2 9/23/19 1:41 PM Picasso’s Demoiselles Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 Blier_6pp.indd 3 9/23/19 1:41 PM © 2019 Suzanne Preston Blier All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk. Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill. Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro and The Sans byBW&A Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Blier, Suzanne Preston, author. Title: Picasso’s Demoiselles, the untold origins of a modern masterpiece / Suzanne Preston Blier. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018047262 (print) LCCN 2019005715 (ebook) ISBN 9781478002048 (ebook) ISBN 9781478000051 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478000198 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973. Demoiselles d’Avignon. | Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973—Criticism and interpretation. | Women in art. | Prostitution in art. | Cubism—France. Classification: LCC ND553.P5 (ebook) | LCC ND553.P5 A635 2019 (print) | DDC 759.4—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047262 Cover art: (top to bottom): Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, detail, March 26, 1907. Museum of Modern Art, New York (Online Picasso Project) opp.07:001 | Anonymous artist, Adouma mask (Gabon), detail, before 1820. Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Photograph by S. P. -

5- Les Primitifs Modernes (Wilhelm Uhde)

5- Les Primitifs modernes (Wilhem Uhde) U.I.A. Histoire de l’Art, Martine Baransky Année 2017-2018 Henri ROUSSEAU (1844-1910) 01 Henri Rousseau dans son atelier. 02 Henri Rousseau Moi-même, 1890, huile sur toile, 146 x 113, Prague, Galerie nationale. 03 Henri Rousseau, Autoportrait de l'artiste à la lampe, 1902-03, huile sur toile, Paris, Musée Picasso. 04 Henri Rousseau, Portrait de la seconde femme de l'artiste, 1903, huile sur toile, 23 x 19, Paris, Musée Picasso. 05 Henri Rousseau, L'enfant à la poupée, vers 1892, huile sur toile, 100 x 81, Paris, Musée de l'Orangerie. 06 Henri Rousseau, Pour fêter bébé, 1903, huile sur toile, 406 x 32,7, Wintherthur, Kunstmuseum. 07 Henri Rousseau, Le Chat tigre, huile sur toile, Coll. Privée. 08 Laval, La Porte Beucheresse. 09 à 014 Laval, Notre-Dame d'Avesnière et ses chapiteaux. 015 Henri Rousseau, Enfant à la poupée et Pablo Picasso, Maya à la poupée. 016 Pablo Picasso devant un tableau d’Henri Rousseau, Portrait d'une femme, 1895, huile sur toile, 160,5 x 105,5, Paris, Musée Picasso. 017 Henri Rousseau, Portrait d'une femme, 1895, huile sur toile, 160,5 x 105,5, Paris, Musée Picasso. 018 Henri Rousseau, Portrait de Madame M., 1895-97, huile sur toile 198 x 115, Paris, Musée d'Orsay. 019 Henri Rousseau, La Noce, vers 1905, huile sur toile, 133 x 114, Paris, Musée de l'Orangerie. 020 Henri Rousseau, La Carriole du père Junier, 1908, huile sur toile, 97 x 129, Paris, Musée de l'Orangerie.