Sea Breakers by Dina Dwyer Unsure of What To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Police Search Murdered Man's Home

The Pickering 52 PAGES ✦ Metroland Durham Region Media Group ✦ WEDNESDAY, APRIL 12, 2006 ✦ Optional delivery $6 / Newsstand $1 CRUISIN’ IN PICKERING SOFT-TOP HYBRID Skate club travels Saab rolls out around the world the world’s first Page B1 Wheels pullout [ Briefly ] Motorist struck, Police search murdered man’s home hurt in Pickering PICKERING —A motorist Durham officers at biker tinue their investigation into a homi- in the investigation, Det.-Sgt. Kleum ues. sustained serious injuries Friday cide here. said. Police believe Mr. Douse’s beaten evening after being struck while massacre victim’s house Durham police have been at the “We have another interest in the body was transported to rural Pickering changing a tire on Hwy. 401 in looking for leads in Keswick home of slaying victim Jamie property and that’s why we’re there,” and dumped in a wood lot in a field Pickering. Flanz for the past couple of days, se- he said Tuesday morning. “We’re pre- north of Concession 7, just east of the Whitby OPP said the man got Pickering case curing the Hattie Court house until a paring a search warrant and we’ll ex- York-Durham Line. A man out walking out of his car on the left shoulder search warrant is obtained. Investiga- ecute it, hopefully, later today.” his dog discovered the body Dec. 8, a of the westbound lanes at Rouge- mount Drive around 7:45 p.m. to tors want to search the property once Det.-Sgt. Kleum would not describe couple of days after Mr. Douse, 35, and By Jeff Mitchell more for leads in the December 2005 the 37-year-old Mr. -

Leve Level 3 Advanced Technical Diploma in Barbering 6002-030 / 6002-530

Leve Level 3 Advanced Technical Diploma in Barbering 6002-030 / 6002-530 Part of 6002-30 October 2017 Version 1.2 Guide to the examination Document version control Version and Change detail Section date 1.2 Amendment to number of resit Details of the exam October 2017 opportunities 2 Who is this document for? This document has been produced for centres who offer City & Guilds Level 3 Advanced Technical Diploma in Barbering. It gives all of the essential details of the qualification’s external assessment (exam) arrangements and has been produced to support the preparation of candidates to take the exam/s. The document comprises four sections: 1. Details of the exam. This section gives details of the structure, length and timing of the exam. 2. Content assessed by the exam. This section gives a summary of the content that will be covered in each exam and information of how marks are allocated to the content. 3. Guidance. This section gives guidance on the language of the exam, the types of questions included and examples of these, and links to further resources to support teaching and exam preparation. 4. Further information. This section lists other sources of information about this qualification and City & Guilds Technical Qualifications. 3 1. Details of the exam External assessment City & Guilds Technical qualifications have been developed to meet national policy changes designed to raise the rigour and robustness of vocational qualifications. These changes are being made to ensure our qualifications can meet the needs of employers and Higher Education. One of these changes is for the qualifications to have an increased emphasis on external assessment. -

Livingston Police Officers Association Shall Receive a Base Salary Adjustment on Such Dates As Listed Below

Memorandum of Understanding 07/01/2018 – 06/30/2021 Operating Engineers Local #3 on behalf of the Livingston Police Officers’ Association and the City of Livingston Livingston Police Officers’ Association Memorandum Of Understanding TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1. TERMS OF AGREEMENT ........................................................................ 5 SECTION 2. PURPOSE ................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3. RECOGNITION ......................................................................................... 5 SECTION 4. UNION SECURITY .................................................................................... 6 4.1 Dues Deduction .................................................................................................... 6 4.2 Communications With Employees ........................................................................ 6 4.3 Advance Notice .................................................................................................... 6 4.4 List of Employees ................................................................................................. 6 SECTION 4A. AB 119………………………………………………………………………….6 SECTION 5. CITY RIGHTS/EMPLOYEE RESPONSIBILITIES ..................................... 7 SECTION 6. NO DISCRIMINATION .............................................................................. 7 SECTION 7. UNION REPRESENTATIVES/ASSOCIATION MEMBERS ....................... 7 7.1 Representatives ................................................................................................... -

Tools of Ignorance

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2011 Tools of Ignorance Nicholas Mainieri University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Mainieri, Nicholas, "Tools of Ignorance" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 137. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/137 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tools of Ignorance A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre, and Communication Arts The Creative Writing Workshop By Nicholas Mainieri B.A. University of Notre Dame, 2006 May 2011 2011, Nicholas Mainieri ii For my parents. iii Acknowledgements There is not enough room on this single page to adequately thank all of -

Meshal V. Higgenbotham

Case 1:09-cv-02178-EGS Document 3 Filed 11/10/09 Page 1 of 51 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AMIR MESHAL, c/o ACLU, 125 Broad St., 18th floor, New York, NY 10004, Plaintiff, v. No. 09-cv-____ CHRIS HIGGENBOTHAM, FBI Supervising Special Agent, in his individual capacity; JURY TRIAL DEMANDED STEVE HERSEM, FBI Supervising Special Agent, in his individual capacity; TWO UNKNOWN NAMED EMPLOYEES, OFFICERS, OR AGENTS OF THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT, in their individual capacities; JOHN and JANE DOES 3-10, Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR DAMAGES AND DECLARATORY RELIEF (Violation of Fourth and Fifth Amendment Rights, Illegal Interrogation, Illegal Proxy Detention, Illegal Rendition, Torture) INTRODUCTION 1. Amir Meshal is a United States citizen who was born and raised in New Jersey. Mr. Meshal is also a Muslim. In 2006, he decided to visit Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, to enrich his study of Islam after the country’s volatile political situation had largely stabilized. 2. On or about January 24, 2007, while fleeing Somalia with other civilians after violence had erupted, Mr. Meshal was apprehended in a joint U.S.-Kenyan-Ethiopian operation along the Somalia-Kenya border. During the next four months and three days, Case 1:09-cv-02178-EGS Document 3 Filed 11/10/09 Page 2 of 51 he was detained in three different countries without ever being charged, without ever being granted access to counsel, and without ever being presented before a judicial officer. Upon information and belief, Plaintiff’s detention without due process was at the direction or behest of U.S. -

Barbershop Zebra Puzzle

Barbershop Zebra Puzzle Five men are side by side at a barbershop getting new beard styles. Each one is using a cape, talking about something with his barber and getting a new beard style. Which customer wants the goatee beard? Cape: black, blue, green, red, white Talking: cars, economy, politics, religion, sports Name: Dane, Lee, Martin, Simon, Randy Age: 30 years, 35 years, 40 years, 45 years, 50 years Beard: anchor, chinstrap, goatee, mutton chops, van Profession: accountant, musician, programmer, dyke salesman, teacher Chair #1 Chair #2 Chair #3 Chair #4 Chair #5 Cape Name Beard Talking Age Profession Dane is at the fourth chair. Simon is next to the man using the Blue cape. The customer talking about Economy is exactly to the The Teacher is exactly to the right of the 35 years old left of the customer talking about Cars. customer. The Musician is next to the man using the Black cape. The customer that wants the Van dyke beard is exactly to the left of the 45 years old man. Randy is next to Dane. Martin is somewhere between the man that wants the The oldest man is exactly to the right of the man Van dyke beard and the man talking about Politics, in talking about Economy. that order. The Salesman is either at the first or at the last chair. The youngest costumer is next to the man talking The customer who wants the Chinstrap beard is about Sports. exactly to the left of Dane. Simon is at one of the ends. The man using the Blue cape is somewhere between The man using the White cape is next to the the man talking about Economy and Dane, in that Accountant. -

The Best Beards in Recent Memory: a List

OCTOBER 31, 2007 • CSWEEKLY.COM • CHICAGO SPORTS WEEKLY | 11 LISTS Cloaked in Glory The best beards in recent memory: a list. Niedermayer it’s Chuck Norris Trophy o’clock shadow to mustache, but his - BY ADAM GODSON - for the finest playoff beard of them beard simply didn’t reach his potential all. Could it be a coincidence that the until he left the Windy City. In 1984, s the Bears struggle to Center won the Conn Smyth Trophy, his finest season, he could have starred find consistency at the as well? in Cavemen without having a makeup quarterback position, a crew. simple solution rests on Rick Sutcliffe - At various times Atheir very sideline—Kyle Orton. Yes, in his career, Sutcliffe went with Bill Walton - Bearded Bill that Kyle Orton. the7 ‘stache, the goatee and the beard, Walton as a player was fun, Sure, Orton had his chance in 2005 but he was never better than when unusual3 and goofy. Clean shaven Bill and put up the worst qualifying passer he sported the full mandible mane. Walton as a broadcaster is obnoxious, rating in league history, but that was Old Redbeard wasn’t a star with the arrogant, and annoying. You do the a different, unbearded Kyle Orton. Dodgers where he went with the lip math. All season it’s been impossible for broom look, he was a star when his TV cameras to pan the Bears sideline folicles ran wild in Chicago. Mike Piazza - In terms of facial without eventually coming to a shot of hair, Piazza sported a goatee or Orton’s magestic neck beard. -

Gaycalgary and Edmonton Magazine #55, May 2008 Table of Contents 5 Music Lives Here Letter from the Publisher

May 2008 Issue 55 FREE of charge OOnene oonn OOnene IInterviews:nterviews: FFairyTalesairyTales X GGeorgeeorge TakeiTakei X MMarksarks tthehe SSpotpot fforor TTenen YYearear AAnniversarynniversary SSportyporty SSpicepice PPaulaul VVickersickers AAndnd MMORE!ORE! PPre-Pridere-Pride GuideGuide EEarlyarly IInfonfo oonn PPageage 1144 GGayCalgaryayCalgary atat thethe JunosJunos FFeist,eist, BBublé,ublé, RRussellussell PPeterseters aandnd mmore!ore! >> STARTING ON PAGE 16 GLBT RESOURCE • CALGARY & EDMONTON 2 gaycalgary and edmonton magazine #55, May 2008 Table of Contents 5 Music Lives Here Letter from the Publisher Established originally in January 1992 as Men For Men BBS by MFM 7 FairyTales Communications. Named changed to X Marks the Spot for Ten Year Anniversary GayCalgary.com in 1998. Stand alone company as of January 2004. First Issue 9 GayCalgary at the Junos of GayCalgary.com Magazine, November A Look at Canadian Music’s Biggest Week 2003. Name adjusted in November 2006 to GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine. 11 RENT 63 Publisher Steve Polyak & Rob Diaz-Marino, Experience a Season of Love [email protected] 12 Theory of a Deadman Editor Rob Diaz Marino, editor@gaycalgary. 16 com Bearing their Scars and Souvenirs Original Graphic Design Deviant Designs 14 Pre-Pride Event Listing Advertising Calgary and Edmonton Steve Polyak [email protected] Contributors 16 Map & Event Listings Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino, Jason Clevett, Find out what’s happening Jerome Voltero, Kevin Alderson, Allison Brodowski , Mercedes Allen, Stephen Lock, Dallas Barnes, Benjamin Hawkcliffe, Andrew 23 When the Past Returns Collins, Felice Newman, Romeo San Vicente, ...to Bite Us in the Butt and the Gay and Lesbian Community of Calgary and Edmonton 25 Q Scopes Photographer “Articulate conflicts, Cancer!” Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz-Marino Videographer 26 Adult Film Review Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz-Marino Berlin, Itch, Dudes and Holes Please forward all inquiries to: GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine 28 Deep Inside Hollywood Suite 403, 215 14th Avenue S.W. -

Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley A

Building Home: Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sean P. Gleason August 2017 © 2017 Sean P. Gleason. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Building Home: Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley by SEAN P. GLEASON has been approved for the School of Communication Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Devika Chawla Professor of Communication Studies Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract GLEASON, SEAN P., Ph.D., August 2017, Communication Studies Building Home: Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley Director of Dissertation: Devika Chawla Dwelling entails the consumption of resources. Every day others die so that we may live. I realize this simple premise after fieldwork. For six months, during the spring and summer of 2016, I visited 13 southern Ohio homesteads interviewing an intergenerational population, ranging in age from 23-65, about their decision live off-grid in the Ohio River Valley as a form of environmental activism. During fieldwork, I helped participants mix sand, straw, and clay to create cob—one of the earliest-recorded building materials. I attended workshops on permaculture and tiny homes. My participants told me why they chose to build with rammed earth, citing examples from the 11th and 12th centuries. I learned about off-grid living and how to recycle rainwater. I built windows with salvaged wine bottles and framed walls from scrap tires. -

The Reserve Record Hudson, Ohio VOL

The longest-running newspaper in historic The Reserve Record Hudson, Ohio VOL. CI....No. 4 WESTERN RESERVE ACADEMY, HUDSON, OHIO. NOVEMBER 2014 Wonderful Weekend of Wonka Spizzwinks Stun Students Beards, ’Burns, and Buzzcuts Reaction to Recent Dismissals Students celebrate spirit, sweets and Yale’s a cappella group wows audience Faculty refine facial follicles; students Fleischmann and Bohan make case for a sweethearts during Homecoming week. with wit, humor and harmonies. display different dazzling ’dos. stronger, more inclusive community. PAGE 3| COMMUNITY PAGE 4 | ARTS PAGE 6-7 | CENTERFOLD PAGE 9 | OPINION Lake Ridge Hosts Forum the media’s portrayal of Arabs By CHARLES feeds into negative stereotypes. PRENDERGAST ’15 She also talked about the use of Every year since 2002, Lake the term “terrorist” and how it Ridge Academy in North Rid- is almost exclusively applied to geville, Ohio has held a diver- Middle Easterners and Arabs. sity forum featuring a different After the presentation, the stu- speaker and topic each year. dents split into smaller groups On Nov. 7, 22 Western Reserve for discussion, where they fur- Academy students traveled with ther considered media portrayal the club Celebrating Heritage, of people from the Arab Middle Ethnicity, Religion, Identity, East and how to end the stereo- Socio-Economic Status and Hu- types associated with it. CHER- manity of All Abilities (CHER- ISH club president Sophia Cau- ISH), to join hundreds of stu- sey ‘15 discussed with peers how dents from area schools at this “Hollywood makes it easier for JENNY XU all-day event, continuing a trend us to stomach what’s going on, Students and faculty from WRA and Caterham visited the United States Capitol Building. -

University of Nevada, Reno an ACCUMULATION of SMALL

University of Nevada, Reno AN ACCUMULATION OF SMALL THINGS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in English by Nathaniel Perry Christopher Coake, Thesis Advisor May 2018 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by NATHANIEL PERRY Entitled An Accumulation Of Small Things be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Christopher Coake, MFA, Advisor Sara Hulse, MFA, Committee Member Michael Branch, Ph.D, Committee Member Marian Berryhill, Ph.D, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2018 i ABSTRACT An Accumulation of Small Things is a collection of short stories rooted heavily in place – both the Texas Gulf Coast and the American West. Drawing on the traditions of other masters of the short story and Southern humor such as Barry Hannah and George Singleton, this is a collection which repeatedly explores the complexity of relationships, men navigating the expectations of masculinity, and the idea of self-mythologizing. Leaning heavily on first-person narration, these are stories particularly concerned with character, dialect, and voice. Spanning ten short stories, An Accumulation of Small Things is a completed work at approximately 40,000 words. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS SUCH HEALING IN SMALL SPACES…………………………………….… 1 AN ACCUMULATION OF SMALL THINGS……………………………….. 25 THE PANTY INCIDENT OF SPRING, 2006………………………………… 38 BURNING LOVE……………………………………………………………… 50 HUNLEY DAY………………………………………………………………… 61 RANDAL-LIFE CRISIS……………………………………………………….. 74 FAMILY PROBLEMS………………………………………………………… 85 ONLY TEMPORARY………………………………………………………… 96 BAYOU CORNE……………………………………………………………… 102 THERE WAS NO WAY THAT LED ANYWHERE BUT HERE…………… 117 1 SUCH HEALING IN SMALL SPACES The tablecloth in front of him was wrinkled, just like Arthur’s shirt. -

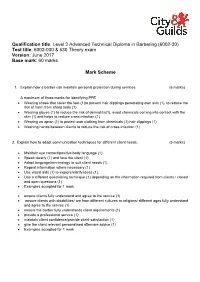

Qualification Title: Level 3 Advanced Technical Diploma in Barbering (6002-30) Test Title: 6002-030 & 530 Theory Exam Version: June 2017 Base Mark: 60 Marks

Qualification title: Level 3 Advanced Technical Diploma in Barbering (6002-30) Test title: 6002-030 & 530 Theory exam Version: June 2017 Base mark: 60 marks Mark Scheme 1. Explain how a barber can maintain personal protection during services. (6 marks) A maximum of three marks for identifying PPE. Wearing shoes that cover the feet (1)to prevent hair clippings penetrating own skin (1), to reduce the risk of harm from sharp tools (1) Wearing gloves (1) to reduce the risk of dermatitis(1), avoid chemicals coming into contact with the skin (1) and helps to reduce cross infection (1) Wearing an apron (1) to protect own clothing from chemicals (1) hair clippings (1) Washing hands between clients to reduce the risk of cross-infection (1) 2. Explain how to adapt communication techniques for different client needs. (5 marks) Maintain eye contact/positive body language (1) Speak clearly (1) and face the client (1) Adapt language/terminology to suit client needs (1) Repeat information where necessary (1) Use visual aids (1) to explore/clarify ideas (1). Use a different questioning technique (1) depending on the information required from clients / closed and open questions (1) Examples accepted for 1 mark ensure clients fully understand and agree to the service (1) ensure clients with disabilities/ are from different cultures or religions/ different ages fully understand and agree to the service (1) ensure the barber fully understands client requirements (1) provide a professional service (1) maintain client confidence/provide client satisfaction (1) give the client relevant personalised aftercare advice (1) Examples accepted for 1 mark 3.