The Lives of Others(Germany, 2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presseheft S

Sommer ’04 Ein Film von Stefan Krohmer nach einem Drehbuch von Daniel Nocke mit Martina Gedeck, Robert Seeliger, Peter Davor, Svea Lohde, Lucas Kotaranin Eine Ö Filmproduktion von Katrin Schlösser und Frank Löprich P R E S S E H E F T KINOSTART: 19. OKTOBER 2006 Pressematerial: www.alamodefilm.de Gefördert von der FilmFörderung Hamburg GmbH Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Schlei Ostsee GmbH Pressekontakt: Verleih: Produktion: ZOOMMEDIENFABRIK GmbH Alamode Film Ö Filmproduktion Kerstin Hamm Nymphenburger Str. 36 Langhansstraße 86 Schillerstrasse 94 80335 München 13086 Berlin 10625 Berlin 0 89/17 99 92 10 0 30/44 67 26 0 030/31 80 26 74 0 89/17 99 92 13 0 30/44 67 26 26 030/31 50 68 58 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] INHALT Besetzung 3 Stab 4 Kurzinhalt 5 Langinhalt 5 Pressenotiz 6 Statement von Stefan Krohmer und Daniel Nocke 7 Produktionsnotiz von Katrin Schlösser, Ö Filmproduktion 7 Interview mit Stefan Krohmer 8 Viten Martina Gedeck 9 Robert Seeliger 10 Peter Davor 11 Svea Lohde 12 Lucas Kotaranin 12 Stefan Krohmer 13 Daniel Nocke 14 Patrick Orth 15 Weitere Informationen 16 Die Schlei-Ostsee-Region und die Schlei Ostsee GmbH 17 2 BESETZUNG Martina Gedeck Miriam Peter Davor André Robert Seeliger Bill Svea Lohde Livia Lucas Kotaranin Nils Nicole Marischka Grietje Gabor Altorgay Daniel Michael Benthin Arzt 3 STAB Regie Stefan Krohmer Drehbuch Daniel Nocke Produktion Ö Filmproduktion GmbH Produzentin Katrin Schlösser Redaktion Sabine Holtgreve (SWR) Bettina Reitz (BR) Barbara Buhl (WDR) Georg Steinert (ARTE) Kamera Patrick Orth Licht Theo Lustig Ton Steffen Graubaum Ausstattung Silke Fischer,Volko Kamensky Kostüm Silke Sommer Maske Liliana Müller Casting Nina Haun Schnitt Gisela Zick Sounddesign Tobias Peper Mischton Stephan Konken 4 KURZINHALT Die augenscheinlich glückliche MIRIAM (Martina Gedeck) verbringt mit ihrem Lebensgefährten ANDRE (Peter Davor), ihrem 15-jährigen Sohn NILS (Lukas Kotaranin), sowie dessen 12-jähriger Freundin LIVIA (Svea Lohde) ihre Sommerferien an der schleswig-holsteinischen Ostseeküste. -

A FILM by Götz Spielmann Nora Vonwaldstätten Ursula Strauss

Nora von Waldstätten Ursula Strauss A FILM BY Götz Spielmann “Nobody knows what he's really like. In fact ‘really‘ doesn't exist.” Sonja CONTACTS OCTOBER NOVEMBER Production World Sales A FILM BY Götz Spielmann coop99 filmproduktion The Match Factory GmbH Wasagasse 12/1/1 Balthasarstraße 79-81 A-1090 Vienna, Austria D-50670 Cologne, Germany WITH Nora von Waldstätten P +43. 1. 319 58 25 P +49. 221. 539 709-0 Ursula Strauss F +43. 1. 319 58 25-20 F +49. 221. 539 709-10 Peter Simonischek E [email protected] E [email protected] Sebastian Koch www.coop99.at www.matchfactory.de Johannes Zeiler SpielmannFilm International Press Production Austria 2013 Kettenbrückengasse 19/6 WOLF Genre Drama A-1050 Vienna, Austria Gordon Spragg Length 114 min P +43. 1. 585 98 59 Laurin Dietrich Format DCP, 35mm E [email protected] Michael Arnon Aspect Ratio 1:1,85 P +49 157 7474 9724 Sound Dolby 5.1 Festivals E [email protected] Original Language German AFC www.wolf-con.com Austrian Film Commission www.oktober-november.at Stiftgasse 6 A-1060 Vienna, Austria P +43. 1. 526 33 23 F +43. 1. 526 68 01 E [email protected] www.afc.at page 3 SYNOPSIS In a small village in the Austrian Alps there is a hotel, now no longer A new chapter begins; old relationships are reconfigured. in use. Many years ago, when people still took summer vacations The reunion slowly but relentlessly brings to light old conflicts in such places, it was a thriving business. -

The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009

In the beginning there is the doing, the social flow of human interaction and creativity, and the doing is imprisoned by the deed, and the deed wants to dominate the doing and life, and the doing is turned into work, and people into things. Thus the world is crazy, and revolts are also practices of hope. This journal is about living in a world in which the doing is separated from the deed, in which this separation is extended in an increasing numbers of spheres of life, in which the revolt about this separation is ubiquitous. It is not easy to keep deed and doing separated. Struggles are everywhere, because everywhere is the realm of the commoner, and the commoners have just a simple idea in mind: end the enclosures, end the separation between the deeds and the doers, the means of existence must be free for all! The Commoner Issue 13 Winter 2008-2009 Editor: Kolya Abramsky and Massimo De Angelis Print Design: James Lindenschmidt Cover Design: [email protected] Web Design: [email protected] www.thecommoner.org visit the editor's blog: www.thecommoner.org/blog Table Of Contents Introduction: Energy Crisis (Among Others) Is In The Air 1 Kolya Abramsky and Massimo De Angelis Fossil Fuels, Capitalism, And Class Struggle 15 Tom Keefer Energy And Labor In The World-Economy 23 Kolya Abramsky Open Letter On Climate Change: “Save The Planet From 45 Capitalism” Evo Morales A Discourse On Prophetic Method: Oil Crises And Political 53 Economy, Past And Future George Caffentzis Iraqi Oil Workers Movements: Spaces Of Transformation 73 And Transition -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

Es Ist Eine Ungerechtigkeit Der Natur, Dass Ein Mensch Nur 80 Jahre Alt Wird

4. Februar 2021 DIE ZEIT No 6 24 UNTERHALTUNG »Feiger Rückzug der Hormone« Das Älterwerden ist Kampf, sagt Ulrich Tukur – ein Kampf, der sich nur mit Poesie ertragen lässt. Begegnung mit einem hochaktiven Künstler, der gerade einen zwiefachen Lockdown überstehen muss es passierte in der Folge noch mehr Unheil. Irgendwann ZEIT: Wo war der wunde Punkt bei Zadek? dachte ich: Vielleicht hat Gott Gerstein wirklich fallen ge- Tukur: Wenn man sich wehrte. Wenn man in der Probe an lassen, und wir kriegen das jetzt auch noch ab! die Rampe ging und sagte: »Wenn von dir noch ein Mal so ZEIT: Weshalb sind gerade Gerstein und Bonhoeffer für was kommt, dann hau ich dir eins aufs Maul.« Er hatte eine Sie so wichtig? Heidenangst vor Leuten, die ihm physisch zu nahe traten. Er Tukur: Sie sind wie zwei Brüder, die die Pole des Mensch- hat das eigentlich gesucht, den Widerspruch. Nur: Die meis- seins verkörpern: das Helle und das Dunkle, das Maßvolle ten haben sich das nicht getraut, sie hatten Angst vor ihm. und das Faustische. Ich frage mich: Wie und warum sind ZEIT: Sie hatten Kontakt mit noch autoritäreren Kunst- sie gescheitert? Wo haben sie gewonnen? Was kann ich systemen – mit Hollywood. Wie war das? daraus lernen? Tukur: Unheimlich. Furchtbar viel Geld, aber gekocht wird ZEIT: Haben Sie auch Menschen gespielt, die grundlos auch nur mit Wasser. Am kuriosesten war folgendes Erleb- böse handeln? nis: Ich bekam eines Tages einen Anruf von einer Wiener Tukur: Nein, die würde ich auch nicht spielen. Das ist Agentur, jemand in den USA wolle mich gerne kennen krank – und deshalb uninteressant. -

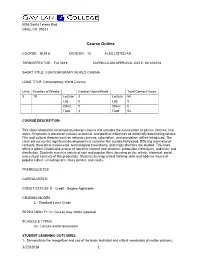

Course Outline 3/23/2018 1

5055 Santa Teresa Blvd Gilroy, CA 95023 Course Outline COURSE: HUM 6 DIVISION: 10 ALSO LISTED AS: TERM EFFECTIVE: Fall 2018 CURRICULUM APPROVAL DATE: 03/12/2018 SHORT TITLE: CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA LONG TITLE: Contemporary World Cinema Units Number of Weeks Contact Hours/Week Total Contact Hours 3 18 Lecture: 3 Lecture: 54 Lab: 0 Lab: 0 Other: 0 Other: 0 Total: 3 Total: 54 COURSE DESCRIPTION: This class introduces contemporary foreign cinema and includes the examination of genres, themes, and styles. Emphasis is placed on cultural, economic, and political influences as artistically determining factors. Film and cultural theories such as national cinemas, colonialism, and orientalism will be introduced. The class will survey the significant developments in narrative film outside Hollywood. Differing international contexts, theoretical movements, technological innovations, and major directors are studied. The class offers a global, historical overview of narrative content and structure, production techniques, audience, and distribution. Students screen a variety of rare and popular films, focusing on the artistic, historical, social, and cultural contexts of film production. Students develop critical thinking skills and address issues of popular culture, including race, class gender, and equity. PREREQUISITES: COREQUISITES: CREDIT STATUS: D - Credit - Degree Applicable GRADING MODES L - Standard Letter Grade REPEATABILITY: N - Course may not be repeated SCHEDULE TYPES: 02 - Lecture and/or discussion STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Demonstrate the recognition and use of the basic technical and critical vocabulary of motion pictures. 3/23/2018 1 Measure of assessment: Written paper, written exams. Year assessed, or planned year of assessment: 2013 2. Identify the major theories of film interpretation. -

Mala Emde Luisa-Céline Gaffron Andreas Lust Noah Saavedra Tonio Schneider

MALA EMDE LUISA-CÉLINE GAFFRON ANDREAS LUST NOAH SAAVEDRA TONIO SCHNEIDER www.undmorgendieganzewelt-film.de undmorgendieganzewelt UndMorgenDieGanzeWelt.film a film by Julia von Heinz with Mala Emde, Noah Saavedra, Tonio Schneider, Luisa-Céline Gaffron and Andreas Lust 2020 - Germany/France - Drama - 2.39 - 110 min International sales International PR German PR Films Boutique claudiatomassini+associates Just Publicity tel: +49 30 6953 7850 Claudia Tomassini Kerstin Böck & Annalena Brandelik [email protected] cell: +49 1732055794 tel: +49 89 20 20 82 60 www.filmsboutique.com [email protected] [email protected] www.claudiatomassini.com AND TOMORROW THE ENTIRE WORLD Cast Luisa MALA EMDE Alfa NOAH SAAVEDRA Lenor TONIO SCHNEIDER Batte LUISA-CÉLINE GAFFRON Dietmar ANDREAS LUST CREW Director JULIA VON HEINZ Screenwriters JULIA VON HEINZ & JOHN QUESTER Producers FABIAN GASMIA, JULIA VON HEINZ Coproducers JOHN QUESTER, THOMAS JAEGER, ANTOINE DELAHOUSSE DoP DANIELA KNAPP Editor GEORG SÖRING Set design CHRISTIAN KETTLER Costumes MAXI MUNZERT Music NEONSCHWARZ Composer MATTHIAS PETSCHE Sound BETTINA BERTÓK Mix VALENTIN FINKE Make-up SILKE DOTZAUER Casting MAI SECK Production companies SEVEN ELEPHANTS GmbH KINGS & QUEENS FILMPRODUKTION GmbH HAIKU FILMS SARL Co-produced by SWR, WDR, BR & ARTE Supported by FFF Bayern, MFG Baden-Württemberg, FFA Filmförderungsanstalt, Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg, French-German Minitraité, CNC Centre national du cinema et de l’image animée, DFFF Deutscher Filmförderfonds Germany, France 2020 TRT: 111 Min The Federal Republic of Germany is a democratic and social federal state. All Germans have the right to resistance against anybody trying to abolish this order if other remedies are not possible. Art. 20, Par. 4 German Constitution AND TOMORROW THE ENTIRE WORLD SYNOPSIS When Luisa leaves her wealthy parents to study law, her best friend introduces her to a rag-tag collective of Antifa activists drawn together by their will to fight for the cause and a disdain of conventions. -

History, Art and Shame in Von Donnersmarck's the Lives of Others

History, Art and Shame in von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others Hans Löfgren University of Gothenburg Abstract. Commentary on the successful directing and scriptwriting debut of Florian von Donnersmarck, The Lives of Others, tends to divide into those faulting the film for its lack of historical accuracy and those praising its artistry and conciliatory symbolic function after the reunification of the GDR and BRD. This essay argues that even when we grant the film’s artistic premise that music can convert the socialist revolutionary into a peaceful liberal, suspending the demand for realism, the politics intrinsic to the film still leads to a problematic conclusion. The stern Stasi officer in charge of the surveillance of a playwright and his actress partner comes to play the part of a selfless savior, while the victimized actress becomes a betrayer. Her shame however, is not shared by the playwright, Dreyman, and the Stasi officer, Wiesler, who never meet eye to eye but instead become linked in a mutual gratitude centering on the book dedicated to Wiesler, written years later when Dreyman learns of the other’s having subversively protected him from imprisonment. Despite superb acting and directing, dependence on such tenuous character development makes the harmonious conclusion of the film ring hollow and implies the need for more serious challenges to German reunification. Keywords. Film, Germany, reunification, symbolic reconciliation, art, humanism, surveillance. Every step you take I’ll be watching you . Oh, can’t you see You belong to me The Police We are accustomed to saying that beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder, and we could easily expand that point by unpacking its figurative meaning, stating more prosaically that an indefinite range of beliefs, values, sentiments and sensations is often ascribed by a spectator, reader, or listener to the text an sich. -

MICHAEL HANEKE SONY WRMI 02Pressbook101909 Mise En Page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 2

SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 1 A film by MICHAEL HANEKE SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 2 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP BLOCK KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Lindsay Macik 853 7th Avenue, #3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 3 X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) A film by MICHAEL HANEKE A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE US RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 30, 2009 Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 www.TheWhiteRibbonmovie.com SONY_WRMI_02Pressbook101909_Mise en page 1 10/19/09 4:36 PM Page 4 Q & A WITH MICHAEL HANEKE Q: What inspired you to focus your story on a village in Northern Germany just prior to World War I? A: Why do people follow an ideology? German fascism is the best-known example of ideological delusion. The grownups of 1933 and 1945 were children in the years prior to World War I. What made them susceptible to following political Pied Pipers? My film doesn’t attempt to explain German fascism. It explores the psychological preconditions of its adherents. What in people’s upbringing makes them willing to surrender their responsibilities? What in their upbringing makes them hate? Q. -

The Conflicted Artist- an Analysis of the Aesthetics of German Idealism in E.T.A

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 The onflicC ted Artist- An Analysis of the Aesthetics of German Idealism In E.T.A. Hoffmann's Artist Leigh Hannah Buches University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Buches, L. H.(2013). The Conflicted Artist- An Analysis of the Aesthetics of German Idealism In E.T.A. Hoffmann's Artist. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2271 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONFLICTED ARTIST: AN ANALYSIS OF THE AESTHETICS OF GERMAN IDEALISM IN E.T.A. HOFFMANN’S ARTIST by Leigh Buches Bachelor of Arts University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Nicholas Vazsonyi, Director of Thesis Dr. Yvonne Ivory, Second Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Leigh Buches, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii Dedication Dedicated to Lauren, my twin sister and lifelong friend. You have always provoked, supported, and enriched my intellectual and artistic pursuits. Thank you for inspiring me to strive towards an Ideal, no matter how distant and impossible it may be. iii Abstract This thesis will analyze the characteristics of the artist as an individual who attempts to attain an aesthetic Ideal in which he believes he will find fulfillment. -

Helmut-Käutner-Preis Für Ulrich Tukur

15052713_168 29. Mai 2015 pld – Pressedienst der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf Helmut-Käutner-Preis für Ulrich Tukur Herausgegeben vom Amt für Kommunikation Rathaus - Marktplatz 2 Düsseldorfer Filmpreis wurde bei einer Feierstunde im Rathaus Postfach 101120 zum 14. Mal verliehen 40002 Düsseldorf Telefon: +49. 211/ 89-93131 Fax: +49. 211/ 89-94179 Der Film- und Theaterschauspieler Ulrich Tukur wurde am Freitag, 29. [email protected] www.duesseldorf.de/presse Mai, mit dem Helmut-Käutner-Preis der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf www.facebook.com/duesseldorf www.twitter.com/duesseldorf ausgezeichnet. Der Preis ist mit 10.000 Euro dotiert und wurde zum 14. Redaktionsteam: Mal vergeben. Oberbürgermeister Thomas Geisel überreichte den Preis mb - Michael Bergmann - 97298 bla - Manfred Blasczyk - 93132 bei einem Festakt im Rathaus. Er würdigte Tukur als "Mimen von be- bu - Michael Buch - 93134 fri - Michael Frisch - 93115 sonderer Art". "Einen Charakterdarsteller zeichnen wir mit der Vergabe jäk - Kerstin Jäckel - 93131 vm - Valentina Meissner - 93111 des Käutner-Preises der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf aus, der uns in mun - Angela Munkert - 97018 pau - Volker Paulat - 93101 seinen Filmen, im Fernsehen als Tatort-Ermittler und auf den Brettern, arz - Dieter Schwarz - 93138 die die Welt bedeuten, zu begeistern weiß. Persönlichkeiten stellt Ulrich Tukur eindringlich vor, die uns unversehens ins Phantasieren und Nach- denken führen. Wie scheinbar leicht ihm das von der Hand geht, offen- bart seine große Kunst", sagte das Stadtoberhaupt. Die Laudatio hielt der Regisseur Dr. Michael Verhoeven. Ulrich Tukur reagierte erfreut auf den Preis: " Was für eine Freude eine Auszeichnung zu erhalten, die sich mit dem Namen eines der größten deutschen Film- regisseure verbindet! Als einer der wenigen hat sich Käutner selbst während der nationalsozialistischen Diktatur eine erstaunliche künst- lerische Unabhängigkeit bewahrt und noch in der Apokalypse des zu Ende gehenden Krieges filmische Meisterwerke von großer Menschlich- keit geschaffen. -

A Film by MICHAEL HANEKE DP RB - Anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 2

DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 1 A film by MICHAEL HANEKE DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 2 X FILME CREATIVE POOL, LES FILMS DU LOSANGE, WEGA FILM, LUCKY RED present THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEISSE BAND) PRESS WOLFGANG W. WERNER PUBLIC RELATIONS phone: +49 89 38 38 67 0 / fax +49 89 38 38 67 11 [email protected] in Cannes: Wolfgang W. Werner +49 170 333 93 53 Christiane Leithardt +49 179 104 80 64 A film by [email protected] MICHAEL HANEKE INTERNATIONAL SALES LES FILMS DU LOSANGE Agathe VALENTIN / Lise ZIPCI 22, Avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie - 75016 Paris Germany / Austria / France / Italy • 2H25 • Black & White • Format 1.85 [email protected] / Cell: +33 6 89 85 96 95 [email protected] / Cell: +33 6 75 13 05 75 in Cannes: Download of Photos & Press kit at: Booth F7 (Riviera) www.filmsdulosange.fr DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 4 A village in Protestant northern Germany. - 2 - - 3 - DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 6 1913-1914. On the eve of World War I. - 4 - - 5 - DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 8 The story of the children and teenagers of a church and school choir run by the village schoolteacher, and their families: the Baron, the steward, the pastor, the doctor, the midwife, the tenant farmers. - 6 - - 7 - DP RB - anglais - VL 12/05/09 10:46 Page 10 Strange accidents occur and gradually take on the character of a punishment ritual.