Cavity Nesting Birds Guild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call of the Chickadee

December, the Doorway to Winter: Call of the Chickadee “Chicka-dee-dee-dee”- this beloved little bird sings its name for the whole world to hear. Black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) are small plump birds, just 4 to 5 inches in length with 8-inch wingspans. Both males and females look alike with soft gray backs and tails, white cheeks, a white chest and belly, and a splash of buff-colored feathers below the wings. Their most distinctive characteristics are their black caps and black masks and throats. The chickadees along with their cousins the Carolina chickadees and tufted titmice are members of a passerine family of birds called Paridae and are often referred to as Parids. They are common sites in the winter landscape as they are non-migratory and stay in their habitats year-round. The range of black-capped chickadees and Carolinas overlap and sometimes the birds interbreed so identification can be confusing. Black-capped chickadees are generally a northern species and are the more common bird here at Duke Farms. Black-capped chickadees live in mixed deciduous and coniferous forests, but readily visit bird feeders in suburban backyards. The black-capped chickadee is found from Alaska east through Canada and throughout the upper two-thirds of the United States. They are year-round residents wherever they live. In winter Chickadees often form small flocks that may include other birds like titmice and nuthatches. They flit from tree branch to tree branch gleaning the dead insects, spider eggs, seeds, mosses and berries from bark and trees. Chickadees often collect and cache their food for future meals, sometimes storing food in holes in snags or under bark or lichen. -

Biology of Mixed Foraging Flocks of Avian Species. Douglass Hathaway Morse Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 Biology of Mixed Foraging Flocks of Avian Species. Douglass Hathaway Morse Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Morse, Douglass Hathaway, "Biology of Mixed Foraging Flocks of Avian Species." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1048. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1048 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—11,400 microfilmed exactly as received MORSE, Douglass Hathaway, 1938- BIOLOGY OF MIXED FORAGING FLOCKS OF AVIAN SPECIES. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1965 Zoology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan BIOLOGY OF MIXED FORAGING FLOCKS OF AVIAN SPECIES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Zoology by Douglass Hathaway Morse B •S•9 Bates College, 1960 M.S., The University of Michigan, 1962 May, 1965 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 thank the Department of Zoology and the Museum of Zoology at Louisiana State University for support and the use of equipment during the course of this study* The International Center for Medical Research and Training extended many courtesies to me during my stay in Costa Rica* Mr* Rex R. -

State of the Park Report, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, Georgia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior State of the Park Report Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park Georgia November 2013 National Park Service. 2013. State of the Park Report for Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. State of the Park Series No. 8. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: Civil War cannon and field of flags at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infrastructure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non- quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. Executive Summary The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of national parks for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. NPS Management Policies (2006) state that “The Service will also strive to ensure that park resources and values are passed on to future generations in a condition that is as good as, or better than, the conditions that exist today.” As part of the stewardship of national parks for the American people, the NPS has begun to develop State of the Park reports to assess the overall status and trends of each park’s resources. -

Comparative Notes on the Life History of the Carolina Chickadee1

COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LIFE HISTORY OF THE CAROLINA CHICKADEE1 RICHARD BREWER knowledge of the life histories of closely related organisms is basic to A understanding their ecological and evolutionary relationships. The Carolina and Black-capped Chickadees (Parus carolinensis Audubon and P. atricapillus Linnaeus) are sibling species occupying essentially allopatric breeding ranges. Where their ranges are contiguous in western Illinois and eastern Missouri, interbreeding apparently occurs, with the production of a zone in which a large proportion of the birds may be hybrids. This paper presents information on certain aspects of the life history of the Carolina Chickadee, along with comparative material on the Black-capped Chickadee and on a population occurring at the line of contact between these two species. Appreciation is due S. C. Kendeigh, who directed the study. Many persons have aided me through discussion or by assistance in field work; particularly, I am indebted to G. W. COX, W. L. Gillespie, and G. C. West. For supplying me with much valuable information through correspondence, I extend my thanks to K. L. Dixon, L. D. K. Lawrence, C. McMullen, J. T. Tanner, and especially to H. Brackbill and A. Laskey whose sizable contributions are cited specifically in the appropriate sections beyond. My wife, Lucy Sharp Brewer, assisted in tending and observing young in the laboratory. Work during the years 1956-1959 was supported by National Science Foundation pre- doctoral fellowships. PROCEDURE Field work was conducted from October 1954 to November 1959. Although some supplemental observations were made in Indiana, Michigan, Mis- souri, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, the principal areas of investiga- tion were the following counties of Illinois: Bond, Champaign, Clinton, Coles, Cumberland, Douglas, Effingham, Fayette, Jackson, Piatt, Randolph, Shelby, Washington, and Williamson. -

Backyard Birds in Texas

Backyard Birds in Texas by Mark klyM In Memory of Rob Fleming ROB FLEMING OCTOBER 27, 1941 MARCH 30, 2003 rob Fleming passed away on March 30, 2003 after a lengthy battle with cancer. rob earned his art degree from Southwest Texas State University and was a successful commercial artist in Houston before opening his own design studio in 1982. rob joined TPWD in 1990 as a staff illustrator and was the Fine art Manager in the Creative Services branch of the Communications Division. rob provided many illustrations for TPWD programs throughout his career and was the winner of numerous awards for his work. leaving the paints to the painters, rob wove his own brand of magic with Prismacolor pencils. Whether a still-life study or a Texas landscape, rob’s technique of color layering created distinctive and truly unique pencil paintings. His colorful pencil studies are in various corporate and private collections throughout the state, and his art graces many TPWD posters, brochures, books and reports. His gentle style and wonderful talent will truly be missed. Cover illustration of Downy Woodpecker by Rob Fleming. Introduction birdwatching, or birding as it is more often referred to, is one of the fastest growing hobbies today. reasons for this popularity are as diverse as birders—aesthetics of the birds, the chance to get out in nature or a simple love for birds. These are some of the common answers to the question “Why do you like birds?” Creating a habitat that is welcoming to the birds that visit your backyard can help you enjoy the hobby of birding without even leaving the comfort of your living room. -

And Carolina Chickadee (P

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Biology and Chemistry 2005 Reproductive Success Across the Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) and Carolina Chickadee (P. carolinensis) Hybrid Zone in Ohio C. L. Bronson Thomas C. Grubb, Jr. Gene D. Sattler Liberty University, [email protected] Michael J. Braun Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Bronson, C. L.; Grubb, Jr., Thomas C.; Sattler, Gene D.; and Braun, Michael J., "Reproductive Success Across the Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) and Carolina Chickadee (P. carolinensis) Hybrid Zone in Ohio" (2005). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 35. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Aiik 122(3):759-772, 2005 © The Americiin Ornithologists' Union, 2005. ^L Printed in USA. REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS ACROSS THE BLACK-CAPPED CHICKADEE {POECILE ATRICAPILLUS) AND CAROLINA CHICKADEE (P. CAROLINENSJS) HYBRID ZONE IN OHIO C. L. BRONSON,' ' THOMAS C. GRUBB, JR./ GENE D. SATTLER,' AND MICHAEL J. 'Dqmrtiticnt of Evolution. Ecohi^y, and Organlsmal Biology, The Ohio Staff Uiiivcrsifii, 318 West Tllli AveiUK Columims, Ohio 43210. USA: 'Di-piut)Jiciit of Biolo;^y mid Cliemistri/, Libert]/ Uniz'crsity, 1971 University Boiilcvnrii, i\/mhbuy^, Vir^iniiJ 24502, USA; mid iciit ofVcrldinUe Zoolo;^y, Nntioiuil Miisciofi ofNntiirnl History, Siiiillisoniiin Institution, 4210 Silver tliil Roud. -

Variation in Chick-A-Dee Calls of a Carolina Chickadee Population, Poecile Carolinensis: Identity and Redundancy Within Note Types Todd M

Variation in chick-a-dee calls of a Carolina chickadee population, Poecile carolinensis: Identity and redundancy within note types Todd M. Freeberg,a) Jeffrey R. Lucas, and Barbara Clucasb) Department of Biological Sciences, Lilly Hall, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 ͑Received 21 February 2002; accepted for publication 14 January 2003͒ Chick-a-dee calls of chickadee species are structurally complex because calls possess a rudimentary syntax governing the ordering of their different note types. Chick-a-dee calls were recorded in an aviary from female and male birds from two field sites. This paper reports sources of variation of acoustical parameters of notes in these calls. There were significant sex and microgeographic differences in some of the measured parameters of the notes in the calls. In addition, the syntax of the call itself influenced characteristics of each of the notes. For example, calls with many introductory notes began with a note of higher frequency and longer duration, relative to calls with few introductory notes. Furthermore, the number of introductory notes influenced frequency and duration components of notes later in the call. Thus, single notes are predictive of the note composition of the signaler’s call. This suggests that a receiver might gain the meaning in the call even if it hears only part of the call. Further, single notes within these complex calls can contain information enabling receivers to predict the sex of the signaler, and whether it is from the local population. © 2003 Acoustical Society of America. ͓DOI: 10.1121/1.1559175͔ PACS numbers: 43.80.Ka, 43.80.Ev, 43.80.Lb ͓WA͔ I. -

Tufted and Black-Crested—Both Species of Titmouse Favor Texas

Texas Bluebird Society Newsletter ▪ Volume 12. Issue 2 MAY 2013 Other Cavity-Nesters: Tufted and Black-Crested—Both Species of Titmouse Favor Texas By Helen Munro, New Texas Bluebird Society member. Past President and Editor of the North Carolina Bluebird Society The Eastern Bluebird is the “poster child” for the secondary cavity nesters. Secondary cavity nesters are the birds that cannot make their own cavities in trees and rely on the work of woodpeckers, rotten limbs falling out leaving knotholes, newspaper tubes, mail- boxes, and, of course, nestboxes supplied by thousands of individ- uals, member and non-members of bluebird societies, throughout the North American continent. This activity has moved the blue- birds to a secure place in our environment. The bluebird recovery has been so successful that people doing research on the Brown-headed Nuthatch, another secondary cavity nester, have asked bluebird enthusiasts in and near pine forests to reduce the hole size in the standard nestboxes from one and a half inch to one inch. By attaching a washer with a one inch opening, the Brown-headed Nuthatch uses the early nesting period, and removal of the washer invites the bluebirds to take the second nesting cycle. However, the star of this article is the Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus Black-Crested Titmouse (above photos) is only found in bicolor). Its grey crest, placed like a jaunty hat on its head, makes it Texas and Mexico. Tufted Titmouse lives here year-round. easy to pick out of a crowd. Its five and a half inch body is slightly larger than the four and half inch Carolina Chickadee and the three and half inch Brown-headed Nuthatch. -

Winter Bird Highlights

Winter Bird Highlights FROM PROJECT FEEDERWATCH 2018–19 FOCUS ON CITIZEN SCIENCE • VOLUME 15 Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- A FeederWatcher photo on the ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2019, is brought to you by cover of a new book! Project FeederWatch, a research and education pro- ject of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the n upcoming book, Wildlife Disease Ecology, efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. features a chapter Project FeederWatch Staff by Cornell Lab or- WILDLIFE DISEASE ECOLOGY A Linking Theory to Data and Application Cornell Lab of Ornithology nithologists and House Finch Edited by Kenneth Wilson, Andy Fenton and Dan Tompkins Emma Greig eye disease researchers André Project Leader and Editor Anne Marie Johnson Dhondt and Wes Hochachka. Project Assistant According to the publisher, Holly Faulkner Project Assistant Cambridge University Press, David Bonter “Each chapter in the book in- Director of Citizen Science Wesley Hochachka troduces a host and disease Senior Research Associate and explains how that system has aided our general Bird Studies Canada understanding of the evolution and spread of wildlife Kerrie Wilcox diseases, through the development and testing of im- Project Leader Rosie Kirton portant epidemiological and evolutionary theories.” Project Support The book’s cover (pictured above) has a photo of a Kristine Dobney Project Assistant House Finch with eye disease taken by FeederWatcher Jody Allair Director of Citizen Science Gary Mueller. The book is scheduled for publication in Denis Lepage November. -

42. Chickadees, Nuthatches, Titmouse and Brown Creeper These Woodland Birds Are Mainly Year-Round Residents in Their Breeding Areas

42. Chickadees, Nuthatches, Titmouse and Brown Creeper These woodland birds are mainly year-round residents in their breeding areas. They become most apparent in fall and winter when all four types may occasionally be seen together, along with downy woodpeckers and kinglets, in mixed-species foraging flocks. In these groupings, the greater number of eyes may improve foraging efficiency and detect potential predators. Pennsylvania’s two chickadee species and the tufted titmouse belong to Family Paridae—omnivorous feeders that cache excess seeds in holes or bark crevices, remember the locations, and return later to eat the food. The two nuthatch species are in Family Sittidae. They glean insect food from the trunks of trees and also eat nuts. Their common name derives from the way they “hack” nuts apart using their stout pointed bills. Taxonomists place the brown creeper in Family Certhiidae, a group that includes ten species, eight of which inhabit Europe and Asia and another India and Africa. The brown creeper is the only species of this family found in black-capped North America. chickadee Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) — A black cap and bib, buffy flanks, and a white belly mark this small (five eat wild berries and the seeds of various plants including inches long), spunky bird. Chickadees have short, sharp ragweed, goldenrod and staghorn sumac. Seeds and the bills and strong legs that let them hop about in trees and eggs and larvae of insects are important winter staples. cling to branches upside down while feeding. They fly in In the fall, chickadees begin storing food in bark crevices, an undulating manner, with rapid wingbeats, rarely going curled leaves, clusters of pine needles, and knotholes. -

Winter Bird Highlights

Winter Bird Highlights FROM PROJECT FEEDERWATCH 2017–18 FOCUS ON CITIZEN SCIENCE • VOLUME 14 Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- Gray Jay renamed Canada Jay ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2018, is brought to you by Project FeederWatch, a research and education pro- n 1957, the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) ject of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies changed the name of the Canada Jay to Gray Jay, Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. much to the dismay of the Canadian birding com- I Project FeederWatch Staff munity, whose members were also disappointed that the American, rather than Canadian, spelling of “gray” Cornell Lab of Ornithology Emma Greig was adopted. This past spring, the AOU voted to re- Project Leader and Editor store the name to Canada Jay, putting an end to the de- Anne Marie Johnson Project Assistant cades-long debate. The new name will appear in this Holly Faulkner issue of Winter Bird Highlights and on FeederWatch Project Assistant David Bonter checklists this fall. Welcome back, Canada Jay! Director of Citizen Science Wesley Hochachka Senior Research Associate Diane Tessaglia-Hymes Design Director Bird Studies Canada Kerrie Wilcox Cover: American Goldfinch by Bob Vuxinic Below: Canada Jay by Tamara Reiser Project Leader Rosie Kirton Project Support Kristine Dobney Project Assistant Denis Lepage Senior Scientist Join Project FeederWatch! Anyone in the United States and Canada with an in- terest in birds and a feeder to watch is welcome to join. -

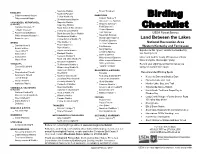

Birding Checklist

Nashville Warbler Brown Thrasher*† KINGLETS Northern Parula*† Golden-crowned Kinglet EMBERIZIDS Yellow Warbler*† Eastern Towhee*† Birding Ruby-crowned Kinglet Chestnut-sided Warbler American Tree Sparrow CHICKADEES, NUTHATCHES, Magnolia Warbler Chipping Sparrow*† & ALLIES Cape May Warbler Field Sparrow*† Carolina Chickadee*† Black-throated Blue Warbler Checklist Vesper Sparrow Tufted Titmouse*† Yellow-rumped Warbler Lark Sparrow Red-breasted Nuthatch Black-throated Green Warbler USDA Forest Service Savannah Sparrow White-breasted Nuthatch*† Blackburnian Warbler Grasshopper Sparrow Brown Creeper Yellow-throated Warbler*† Land Between the Lakes Henslow’s Sparrow Pine Warbler*† WRENS Le Conte’s Sparrow National Recreation Area Prairie Warbler*† Carolina Wren*† Fox Sparrow Western Kentucky and Tennessee Palm Warbler Bewick’s Wren Song Sparrow Bay-breasted Warbler Experience this “green” corridor surrounded by House Wren*† Lincoln’s Sparrow Winter Wren Blackpoll Warbler two flowing rivers. Swamp Sparrow Cerulean Warbler*† Sedge Wren White-throated Sparrow Listen and look for nearly 250 species of birds Black-and-white Warbler*† Marsh Wren White-crowned Sparrow travel along the Mississippi Flyway. American Redstart*† Dark-eyed Junco THRUSHES Prothonotary Warbler*† Record your sightings on this bird list as you Eastern Bluebird*† Lapland Longspur surround yourself with nature. Worm-eating Warbler*† Veery Swainson’s Warbler BLACKBIRDS & ORIOLES Gray-cheeked Thrush Ovenbird*† Bobolink