Catoctin Creek: a Mason Island Complex Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

Program: Michael Barber (Virginia Department of Historic Resources) and Lauren Mcmillan (St

47th Annual Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference March 16-19, 2017 Virginia Beach Resort and Conference Center 2800 Shore Drive Virginia Beach, Virginia 23451 i MAAC Officers and Executive Board President President-Elect Douglas Sanford Gregory Lattanzi Department of Historic Preservation Bureau of Archaeology & Ethnography University of Mary Washington New Jersey State Museum 1301 College Avenue 205 West State Street Fredericksburg, VA 22401 Trenton, NJ 08625 [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer Membership Secretary Elizabeth Moore Eleanor Breen VA Museum of Natural History Office of Historic Alexandria/Alexandria Archaeology 21 Starling Ave 105 N. Union Street, #327 Martinsville, VA 24112 Alexandria, VA 23314 [email protected] [email protected] Recording Secretary Board Member at Large Brian Crane David Mudge Versar, Inc. 2021 Old York Road 6850 Versar Center Burlington, NJ 08016 Springfield, VA 22151 [email protected] [email protected] Board Member at Large/ Journal Editor Student Committee Chair Alexandra Crowder Roger Moeller University of Massachusetts, Boston Archaeological Services 18 Saint John Street Apt. 4 PO Box 386 Boston, MA 02130 Bethlehem, CT 06751 [email protected] [email protected] ii The Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference and its Executive Board express their deep appreciation to the following individuals and organizations that generously have supported the undergraduate and graduate students presenting papers at the conference, including those participating in the student paper competition. D. Brad Hatch Lenny Truitt Michael Madden Claude A Bowen, Jr. The Archaeological Friends of Fairfax County Society of Delaware Archaeology ASV - Col. Howard Archeological Society MacCord Chapter of Maryland David Mudge Dovetail CRG, Inc. -

In the Matter of the Application Of

IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION OF * BEFORE THE BIGGS FORD SOLAR CENTER, LLC FOR A PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION CERTIFICATE OF PUBLIC CONVENIENCE * OF MARYLAND AND NECESSITY TO CONSTRUCT A 15.0 MW SOLAR PHOTOVOLTAIC GENER- * ATING FACILITY IN FREDERICK COUNTY, CASE NO. 9439, MARYLAND * PHASE II PROPOSED ORDER OF PUBLIC UTILITY LAW JUDGE Before: Ryan C. McLean Public Utility Law Judge Issued: August 27, 2020 Table of Contents Appearances ............................................................................................................................ iv I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1 II. Procedural History .......................................................................................................... 4 III. Summary of the Application and Parties’ Positions ....................................................... 8 A. Biggs Ford - The Amended Project ............................................................................. 8 B. PPRP .......................................................................................................................... 16 C. The County ................................................................................................................. 22 D. Staff ............................................................................................................................ 24 E. Biggs Ford’s Rebuttal Testimony ............................................................................. -

Archaeologist Volume 44 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 44 NO. 1 WINTER 1994 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $17.50; husband and wife (one copy of publication) $18.50; Life membership $300.00. EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included in 1994 President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an incor Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 porated non-profit organization. 1994 Vice President Stephen J. Parker, 1859 Frank Drive, BACK ISSUES Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-6642 1994 Exec. Sect. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: 43130, (614)653-9477 Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse.$20.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, 1980's& 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43068, (614) 861-0673 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43064, (614)873-5471 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gen 1994 Immediate Past Pres. -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 43 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 43 NO. 2 SPRING 1993 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first TERM of January as follows: Regular membership $17.50; husband and wife EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS (one copy of publication) $18.50; Life membership $300.00. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included in the member 1994 President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East ship dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an incorporated non Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 profit organization. 1994 Vice President Stephen J. Parker, 1859 Frank Drive, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614)653-6642 BACK ISSUES 1994 Exec. Sect. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43130,(614)653-9477 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H SE. East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse .$20.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, 1980's & 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43068, (614)861-0673 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gener ally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

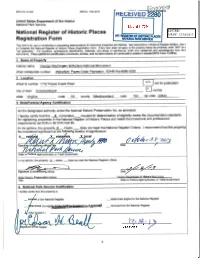

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 0 ·~ 2013 National Register of Historic Places NAT. Re018TiR OF HISTORIC PlACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name George Washington Birthplace National Monument other names/site number Wakefield. Popes Creek Plantation , VDHR File #096-0026 2. Location 1732 Popes Creek Road not for publication street & number L-----' city or town Colonial Beach ~ vicinity state Vir inia code VA county Westmoreland code _ _;_:19'--=-3- zip code -"'2=2:....;.4"""43.;;...._ ___ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _!__nomination_ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .K._ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x_ b state ' Ide "x n J.VIA.rVI In my opinion, the property .x..._ meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

F-7-141 Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area

F-7-141 Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 10-11-2011 CAPSULE SUMMARY Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area MIHJP# F-7-141 Dickerson vicinity Frederick and Montgomery counties, Maryland NRMA=1974 Public The Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area (NRMA) occupies 2,011 acres that includes property along both banks of the lower Monocacy River and most of the Furnace Branch watershed in southeastern Frederick and western Montgomery counties. The area is predominantly rural, comprising farmland and rolling and rocky wooded hills. Monocacy NRMA's main attraction is the Monocacy River, which was designated a Maryland Scenic River in 1974. The NRMA began in 1974 with the acquisition of the 729-acre Rock Hall estate. -

2013 ESAF ESAF Business Office, P.O

BULLETIN of the EASTERN STATES ARCHEOLOGICAL FEDERATION NUMBER 72 PROCEEDINGS OF THE ANNUAL ESAF MEETING 79th Annual Meeting October 25-28, 2012 Perrysburg, OH Editor Roger Moeller TABLE OF CONTENTS ESAF Officers............................................................................ 1 Minutes of the Annual ESAF Meeting...................................... 2 Minutes of the ESAF General Business Meeting ..................... 7 Webmaster's Report................................................................... 10 Editor's Report........................................................................... 11 Brennan Award Report............................................................... 12 Treasurer’s Report..................................................................... 13 State Society Reports................................................................. 14 Abstracts.................................................................................... 19 ESAF Member State Society Directories ................................. 33 ESAF OFFICERS 2012/2014 President Amanda Valko [email protected] President-Elect Kurt Carr [email protected] Past President Dean Knight [email protected] Corresponding Secretary Martha Potter Otto [email protected] Recording Secretary Faye L. Stocum [email protected] Treasurer Timothy J. Abel [email protected] Business Manager Roger Moeller [email protected] Archaeology of Eastern North America -

Monongahela Indians

As part of the U.S. 219 Meyersdale Bypass project, and in keeping with the provisions of the Na- tional Historic Preservation Act, an archaeological survey of the project area was conducted to determine the impact of the roadway construction on cultural resources. The survey identified 68 archaeological sites, of which 21 were evaluated for their eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places. Eight of these sites were ultimately selected for intensive data recovery excavations. The artifacts recovered from the archaeological excavations belong to the State of Pennsylvania and are permanently stored at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. This booklet presents some of the results of research and excavations conducted as part of the project. Special thanks to the communities of Meyersdale and Summit Township, Pennsylvania for their support, interest, and contribution to the success of the archaeological investigations. This work was sponsored by: The United States Department of Transportation, The Federal Highway Administration and The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Engineering District 9-0 1620 North Juniata Street Hollidaysburg, PA 16648 Written By: Varna G. Boyd and Kathleen A. Furgerson Illustrated By: Simon J. Lewthwaite and Jennifer A. Sparenberg Graphic Design By: Julie A. Liptak Edited by: Katherine Marie Benitez (age 13) and Amy Kristina Benitez (age 11) Produced By: Greenhorne & O’Mara, Inc. 1999 The Mystery of the Monongahela Indians Table of Contents Who Were The Monongahela? ……………………………………………... 3 What Is Archaeology? ……………………………………………………..... 5 What Was Daily Life Like? ……………………………………………….... 7 Where Did They Live? …………………………………………………….... 9 What Did They Eat? ……………………………………………………….... 12 What Did They Wear? ……………………………………............................ 14 What Technology Did They Have? ………………………………………... -

G-I-E-013 Meyer Site

G-I-E-013 Meyer Site Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 12-01-2003 G-I-E-013 c. A.D. 1000-1500 Meyer Site Chestnut Grove Road Bethel Private The Meyer site is located on the riverside edge of an alluvial bottom on the west side of the North Branch of the Potomac. The known limits of the site extend about 200' along the river and 100' back from the bank. Test excavations in 1958, 1964, and 1966, by H.T. Wright and Frank R. Corliss, Jr. revealed a deep plowzone of dark-brown sandy humus containing artifacts. Underneath the plowzone is light-yellow, sandy subsoil which is apparently sterile of cultural remains. -

The Barton Site: Thousands of Years of Occupation

VIRTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY’S IMPACT • A MAYA PIONEER • OUR PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS american archaeologyFALL 2003 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 7 No. 3 The Barton Site: Thousands of Years of Occupation 33> $3.95 7525274 91765 archaeological tours led by noted scholars superb itineraries, unsurpassed service For the past 28 years, Archaeological Tours has been arranging specialized tours for a discriminating clientele. Our tours feature distinguished scholars who stress the historical, anthropological and archaeological aspects of the areas visited. We offer a unique opportunity for tour participants to see and understand historically important and culturally significant areas of the world. Robert Bianchi in Egypt 2003 TOURS SRI LANKA MAYA SUPERPOWERS MUSEUMS OF SPAIN Among the first great Buddhist kingdoms, the island of This exciting tour examines the ferocious political Bilbao, Barcelona & Madrid Sri Lanka offers wonders far exceeding its small size. struggles between the Maya superpowers in the Late October 2 – 12, 2003 11 Days As we explore this mystical place, we will have a Classical period including bitter antagonism between Led by Prof. Ori Z. Soltes, Georgetown University glimpse of life under kings who created sophisticated Tikal in northern Guatemala and Calakmul across the irrigation systems, built magnificent temples and huge border in Mexico. New roads will allow us to visit these OASES OF THE WESTERN DESERT dagobas, carved 40-foot-tall Buddhas and one who ancient cities, as well as Copan in Honduras, Lamanai Alexandria, Siwa, Bahariya, Dakhla & Kharga, Luxor chose to build his royal residence, gardens and pools and the large archaeological project at Caracol in Belize October 3 – 20, 2003 18 Days on the top of a 600-foot rock outcropping. -

Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Connecting

CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH CHESAPEAKE NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL CONNECTING TRAILS EVALUATION STUDY 410 Severn Avenue, Suite 405 Annapolis, MD 21403 CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Executive Summary 3 Statement of Study Findings 5 Introduction 9 Research Team Reports 10 Anacostia River 11 Chester River 15 Choptank River 19 Susquehanna River 23 Upper James River 27 Upper Nanticoke River 30 Appendix: Research Teams’ Executive Summaries and Bibliographies 34 Anacostia River 34 Chester River 37 Choptank River 40 Susquehanna River 44 Upper James River 54 Upper Nanticoke River 56 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are truly thankful to the research and project team, led by John S. Salmon, for the months of dedicated research, mapping, and analysis that led to the production of this important study. In all, more than 35 pro- fessionals, including professors and students representing six universities, American Indian representatives, consultants, public agency representatives, and community leaders contributed to this report. Each person brought an extraordinary depth of knowledge, keen insight and a personal devotion to the project. We are especially grateful for the generous financial support that we received from the following private foundations, organizations and corporate partners: The Morris & Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, The Clay- ton Fund, Inc., Colcom Foundation, The Conservation Fund, Lockheed Martin, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, The Merrill Foundation, the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, the Rauch Foundation, The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, Verizon, Virginia Environmental Endowment and the Wallace Genetic Foundation. Without their support this project would simply not have been possible. Finally, we would like to extend a special thank you to the board of directors of the Chesapeake Conser- vancy, and to John Maounis, Superintendent of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Office, for their leadership and unwavering commitment to the Captain John Smith Chesapeake Trail.