Than Camaraderie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Telegraph Letters

Daily Telegraph Letters Arnold at the Proms 10 October 2004 SIR – I wish I could play the cello as elegantly as Julian Lloyd Webber writes (Arts, Mar 6). But it is misleading for him to keep complaining about the “close-ranked, claustrophobic musical establishment of the 1950s and 1960s” who supported avant-garde composers “while dismissing melody and harmony”. The fact is that Sir William Glock at the BBC was an adventurous and generous patron of the widest possible range of music from Machaut, through Monteverdi and Mozart, to Maxwell Davies and countless living composers. He supported the work of Malcolm Arnold and commissioned works from him for the Proms. Lloyd Webber's artful sentence about Arnold's music at the Proms seems to try to conceal the fact that it was actually performed in 1996 and 199, as well as last season: some 24 performances have been heard over the years. Nicholas Kenyon Director, BBC Proms London W1 Glock against the clock 11October 2004 Sir – I feel that William Walton would agree with Lloyd Webber that Malcolm Arnold deserves a celebration (Arts, Mar 6). Laurence Olivier, a very close friend, used to console William by saying: “Just as in the theatre you are seven years in and seven years out; if you live long enough, you will again hear your music played.” I am glad to say that William lived longer than Sir William Glock. Lady Walton Isola d'Ischia, Italy Frets the troubled soul Sir – I was chairman of the avant garde, Arts Council-funded New Macnaghtan concerts in 1976 to 1979: Nicholas Kenyon was on the committee (Arts, Mar 6; Letters Mar 10, 11). -

The Critical Reception of Tippett's Operas

Between Englishness and Modernism: The Critical Reception of Tippett’s Operas Ivan Hewett (Royal College of Music) [email protected] The relationship between that particular form of national identity and consciousness we term ‘Englishness’ and modernism has been much discussed1. It is my contention in this essay that the critical reception of the operas of Michael Tippett sheds an interesting and revealing light on the relationship at a moment when it was particularly fraught, in the decades following the Second World War. Before approaching that topic, one has to deal first with the thorny and many-sided question as to how and to what extent those operas really do manifest a quality of Englishness. This is more than a parochial question of whether Tippett is a composer whose special significance for listeners and opera-goers in the UK is rooted in qualities that only we on these islands can perceive. It would hardly be judged a triumph for Tippett if that question were answered in the affirmative. On the contrary, it would be perceived as a limiting factor — perhaps the very factor that prevents Tippett from exporting overseas as successfully as his great rival and antipode, Benjamin Britten. But even without that hard evidence of Tippett’s limited appeal, the very idea that his Englishness forms a major part of his significance could in itself be a disabling feature of the music. We are squeamish these days about granting a substantive aesthetic value to music on the grounds of its national qualities, if the composer in question is not safely locked away in the relatively remote past. -

Two Serial Pieces Written in 1968 by Pierre Boulez and Isang Yun By

A Study of Domaines and Riul: Two Serial Pieces Written in 1968 by Pierre Boulez and Isang Yun by Jinkyu Kim Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Julian L. Hook, Research Director _______________________________________ James Campbell, Chair _______________________________________ Eli Eban _______________________________________ Kathryn Lukas April 10, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Jinkyu Kim iii To Youn iv Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. v List of Examples ............................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ix List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. xi Chapter 1: MUSICAL LANGUAGES AFTER WORLD WAR II ................................................ 1 Chapter 2: BOULEZ, DOMAINES ................................................................................................ -

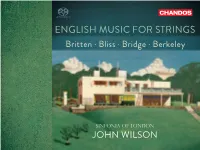

ENGLISH MUSIC for STRINGS Britten • Bliss • Bridge • Berkeley

SUPER AUDIO CD ENGLISH MUSIC FOR STRINGS Britten • Bliss • Bridge • Berkeley Sinfonia of London JOHN WILSON Hampstead, mid-1930s piano,athomeEastHeathLodge, Blüthner Bliss,athislatemother’s Arthur Photographer unknown / Courtesy of the Bliss Collection, with thanks to the late Trudy Bliss English Music for Strings Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, Op. 10 (1937) 23:37 for String Orchestra To F.B. A tribute with affection and admiration 1 Introduction and Theme. Lento maestoso – Allegretto poco lento – 1:31 2 Adagio. Adagio – 1:52 3 March. Presto alla marcia – 1:05 4 Romance. Allegretto grazioso – 1:31 5 Aria Italiana. Allegro brillante – 1:11 6 Bourrée Classique. Allegro e pesante – 1:17 7 Wiener Walzer. Lento – Vivace – Lento – Vivace – [ ] – Vivace – Lento – Tempo I – Lento – Tempo I – Lento – Tempo vivace – 2:05 8 Moto Perpetuo. Allegro molto – 1:00 9 Funeral March. Andante ritmico – Con moto – 3:49 10 Chant. Lento – 1:39 11 Fugue and Finale. Allegro molto vivace – Molto animato – Lento e solenne – Poco comodo e tranquillo – Lento – Più presto 6:34 3 Frank Bridge (1879 – 1941) 12 Lament, H 117 (1915) 3:47 for String Orchestra Catherine, aged 9, ‘Lusitania’ 1915 Adagio, con molto espressione – Poco più adagio Sir Lennox Berkeley (1903 – 1989) Serenade for Strings, Op. 12 (1938 – 39) 13:01 in Four Movements To John and Clement Davenport 13 I Vivace 2:09 14 II Andantino 3:52 15 III Allegro moderato 3:11 16 IV Lento 3:48 4 Sir Arthur Bliss (1891 – 1975) Music for Strings, F 123 (1935) 23:56 Dedicated -

Britten in Beijing

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited February 2013 2013/1 Reich Radio Rewrite Britten in Beijing Steve Reich’s new ensemble work, with first performances in Included in this issue: The Britten centenary sees the composer’s drawings, resulting in a spectacular series of the UK and US in March, draws inspiration from songs by music celebrated worldwide including many animal lanterns handcrafted in Shangdong van der Aa Radiohead. works receiving territorial premieres, from Province. The production used the biblical Interview about his new 3D song through to reworkings by Stravinsky. South America to Asia and the Antipodes. tale of Noah to explore contemporary film opera Sunken Garden “It was not my intention to make anything like As an upbeat to this year’s events, the first ecological concerns. Through a series of ‘variations’ on these songs, but rather to Britten opera was staged in China with a educational projects, Noye’s Fludde provided draw on their harmonies and sometimes Noye’s Fludde collaboration between an illustration of man’s struggle with the melodic fragments and work them into my Northern Ireland Opera, the KT Wong environment and the significance of flood own piece. As to actually hearing the original Foundation and the Beijing Music Festival. mythology to both Chinese and Western cultures. songs, the truth is – sometimes you hear First staged in Belfast Zoo last summer as them and sometimes you don’t.” part of the Cultural Olympiad, Oliver Mears’s Overseas Britten highlights in 2013 include Photo: Wonge Bergmann Reich encountered the music of Radiohead production transferred in October to Beijing as territorial opera premieres in Brazil, Chile, following a performance by Jonny part of the UK Now Festival. -

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES an Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon Sean Shibe guitar Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon conductor Sean Shibe guitar Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016) 1. Concert Overture: Ebb Of Winter ..................................................... 17:41 Hill Runes* 2. Adagio – Allegro moderato ................................................................ 1:58 3. Allegro (with several changes of tempo) ........................................ 0:50 4. Vivace scherzando ............................................................................... 0:48 5. Adagio molto .......................................................................................... 2:27 6. Allegro (dying away into ‘endless’ silence) ..................................... 1:55 7. Last Door Of Light ............................................................................... 16:38 8. Farewell To Stromness* ...................................................................... 4:26 9. An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise ................................................. 12:34 Total Running Time: 59 minutes *solo guitar Recorded at Usher Hall, Edinburgh, UK 14–16 September 2015 Produced by John Fraser (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Recorded by Calum Malcolm (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Post-production by Julia Thomas Cover image by -

Middlebrow Modernism: Britten's Operas and the Great Divide

CHOWRIMOOTOO | MIDDLEBROW MODERNISM Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publication of this book was made possible by generous subventions, awards, and grants from the Institute of Scholarship in the Liberal Arts in Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters; the University of California Press; and the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Middlebrow Modernism CALIFORNIA STUDIES IN 20th-CENTURY MUSIC Richard Taruskin, General Editor 1. Revealing Masks: Exotic Influences and Ritualized Performance in Modernist Music Theater, by W. Anthony Sheppard 2. Russian Opera and the Symbolist Movement, by Simon Morrison 3. German Modernism: Music and the Arts, by Walter Frisch 4. New Music, New Allies: American Experimental Music in West Germany from the Zero Hour to Reunification, by Amy Beal 5. Bartók, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality, by David E. Schneider 6. Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism, by Mary E. Davis 7. Music Divided: Bartók’s Legacy in Cold War Culture, by Danielle Fosler-Lussier 8. Jewish Identities: Nationalism, Racism, and Utopianism in Twentieth-Century Art Music, by Klára Móricz 9. -

STRAVINSKY the SOLDIER’S TALE Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble MENU

Oliver Knussen Conductor • Dame Harriet Walter Narrator Sir Harrison Birtwistle Soldier • George Benjamin Devil STRAVINSKY THE SOLDIER’S TALE Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble MENU Tracklist Credits Producer's Note Programme Note Biographies Oliver Knussen Conductor • Dame Harriet Walter Narrator Sir Harrison Birtwistle Soldier • George Benjamin Devil Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) 1. Fanfare for a New Theatre ..................................................................................................................... 0:47 Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016) arr. Oliver Knussen (b. 1952) 2. Canon ad honorem Igor Stravinsky .................................................................................. 2:10 Harrison Birtwistle (b. 1934) 3. Chorale from a Toy Shop – for Igor Stravinsky (2016 version for winds) .... 1:23 4. Chorale from a Toy Shop – for Igor Stravinsky (2016 version for strings) .. 1:25 Stravinsky The Soldier’s Tale Part One 5. Introduction: The Soldier’s March ...................................................................................... 2:38 6. Music for Scene 1: Airs by a Stream .................................................................................. 6:52 7. The Soldier’s March (reprise) ................................................................................................ 4:33 8. Music for Scene 2: Pastorale ........................................................................................................ 4:54 9. Music for the End -

TEMPO Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana

TEMPO http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM Additional services for TEMPO: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana: Victims of an Exclusion Zone?. Caroline Rae TEMPO / Volume 212 / Issue 212 / April 2000, pp 22 - 30 DOI: 10.1017/S0040298200007580, Published online: 23 November 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0040298200007580 How to cite this article: Caroline Rae (2000). Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana: Victims of an Exclusion Zone?. TEMPO, 212, pp 22-30 doi:10.1017/S0040298200007580 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM, IP address: 131.251.254.238 on 31 Jul 2014 Caroline Rae Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana: Victims of an Exclusion Zone? Until recently, the music of Henri Dutilleux and known more as a concert pianist than as a com- Maurice Ohana was largely overlooked in poser and by 1939 had given recitals at the Salles Britain, despite both composers having achieved Gaveau and Chopin, performed concertos with widespread recognition beyond our shores. In the orchestras of the Concerts Lamoureux and France they have ranked among the leading Pasdeloup, and completed several European composers of their generation since at least the tours. (In 1947 he gave recitals in London at the 1960s and have received many of the highest Wigmore Hall as well as for the BBC Home official accolades. In Britain, the view of French Service.) Indicating the path of his subsequent music since 1945 has often been synonymous compositional development, his recital program- with the music of Olivier Messiaen and Pierre mes reflected a cultural alignment independent Boulez, to the virtual exclusion of others whose of the Austro-German tradition and typically work has long been honoured not only in comprised works by Scarlatti, Chopin, Debussy, France and elsewhere in Europe but in the Ravel and the Spaniards, Falla, Albeniz and wider international arena. -

The Cambridge Companion To: the ORCHESTRA

The Cambridge Companion to the Orchestra This guide to the orchestra and orchestral life is unique in the breadth of its coverage. It combines orchestral history and orchestral repertory with a practical bias offering critical thought about the past, present and future of the orchestra as a sociological and as an artistic phenomenon. This approach reflects many of the current global discussions about the orchestra’s continued role in a changing society. Other topics discussed include the art of orchestration, score-reading, conductors and conducting, international orchestras, and recording, as well as consideration of what it means to be an orchestral musician, an educator, or an informed listener. Written by experts in the field, the book will be of academic and practical interest to a wide-ranging readership of music historians and professional or amateur musicians as well as an invaluable resource for all those contemplating a career in the performing arts. Colin Lawson is a Pro Vice-Chancellor of Thames Valley University, having previously been Professor of Music at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He has an international profile as a solo clarinettist and plays with The Hanover Band, The English Concert and The King’s Consort. His publications for Cambridge University Press include The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet (1995), Mozart: Clarinet Concerto (1996), Brahms: Clarinet Quintet (1998), The Historical Performance of Music (with Robin Stowell) (1999) and The Early Clarinet (2000). Cambridge Companions to Music Composers -

An Interview with Earle Brown Amy C

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Santa Cruz] On: 22 November 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 923037288] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Music Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713455393 An Interview with Earle Brown Amy C. Beal To cite this Article Beal, Amy C.(2007) 'An Interview with Earle Brown', Contemporary Music Review, 26: 3, 341 — 356 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/07494460701414223 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494460701414223 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Contemporary Music Review Vol. 26, Nos. 3/4, June/August 2007, pp. 341 – 356 An Interview with Earle Brown Amy C. -

8 Reverberations of 1968

Part Four: The States of Music 169 8 Reverberations of 1968 Was it really all so vital, so hopeful, so different from any other year? The English middle-class students copying their Paris comrades in college and art school protests against ‘repressive tolerance’ through the summer and autumn of 1968 would have liked to think so. But there was an air of instant mythologizing that seemed unconvincing even at the time. Whatever the bright novelties of Biba or the Beatles, the year’s more serious events in the world at large could only induce a cumulative sense of déjà vu. As Martin Luther King was gunned down like President Kennedy before him, Nixon rose again from the political dead; it was Bloody Sunday once more in Grosvenor Square and Hungary 1956 in Prague. Meanwhile the horrors of post-colonial Africa and Far East dragged on; the shadow of the Bomb continued to loom and the avatars of the growing ecology movement were already warning of a Second Deluge. That anyone might still be around to celebrate the year a quarter of a century later would have seemed one of the unlikelier prophecies of 1968. And to celebrate it how? Had radical protest carried the day, the obvious memento would be Hans Werner Henze’s ‘popular and military oratorio’, The Raft of the Medusa. The scandal of the 1816 shipwreck from which the nobs had escaped in long-boats, abandoning 300 ordinary men, women and children to a raft, had not only inspired Géricault’s famous painting but helped to ferment the revolution of 1848.