Scottish M Usic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3770001904221.Pdf

This is America! Meredith Monk (b. 1942) 1 Ellis Island 3’02 Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story (transcription: John Musto) 2 Prologue 4’18 3 Somewhere 4’29 4 Mambo 2’19 5 Cha-Cha 1’02 6 Meeting Scene 0'41 7 Cool 0’38 8 Fugue 3’02 9 Rumble 2’01 10 Finale 2’27 Philip Glass (b. 1937) Four Movements for Two Pianos 11 Movement 1 6’21 12 Movement 2 4’49 13 Movement 3 6’19 14 Movement 4 5’30 John Adams (b. 1947) Hallelujah Junction 15 Movement 1 6’43 16 Movement 2 2’52 17 Movement 3 5’58 TT: 62’34 3 THIS IS AMERICA! | VANESSA WAGNER & WILHEM LATCHOUMIA Entretien avec Vanessa Wagner et Wilhem Latchoumia Apparu au milieu des années 60 aux États-Unis, le courant minimaliste a longtemps tutoyé l’avant-garde avant de gagner, au fil des ans, une audience beaucoup plus large et de s’imposer comme une étape majeure de la musique contemporaine. Terry Riley, La Monte Young, Steve Reich et Philip Glass, tous américains, sont considérés comme les pionniers de ce courant. Si beaucoup de ces compositeurs contestent l’étiquette minimaliste, réductrice à leurs yeux, leur approche se rejoint dans la recherche de nouvelles structures musicales, comme l’emploi de motifs répétitifs, une certaine forme de dépouillement et l’emploi de certains procédés spécifiques (la technique de « phasing » de Reich, utilisant simultanément des enregistrements avec un léger décalage). Les minimalistes ont intégré de nombreuses influences pour nourrir leur travail, le jazz et l’improvisation pour Terry Riley, la mouvance expérimentale pour La Monte Young, la musique indienne pour Philip Glass, les cultures africaines pour Steve Reich. -

Daily Telegraph Letters

Daily Telegraph Letters Arnold at the Proms 10 October 2004 SIR – I wish I could play the cello as elegantly as Julian Lloyd Webber writes (Arts, Mar 6). But it is misleading for him to keep complaining about the “close-ranked, claustrophobic musical establishment of the 1950s and 1960s” who supported avant-garde composers “while dismissing melody and harmony”. The fact is that Sir William Glock at the BBC was an adventurous and generous patron of the widest possible range of music from Machaut, through Monteverdi and Mozart, to Maxwell Davies and countless living composers. He supported the work of Malcolm Arnold and commissioned works from him for the Proms. Lloyd Webber's artful sentence about Arnold's music at the Proms seems to try to conceal the fact that it was actually performed in 1996 and 199, as well as last season: some 24 performances have been heard over the years. Nicholas Kenyon Director, BBC Proms London W1 Glock against the clock 11October 2004 Sir – I feel that William Walton would agree with Lloyd Webber that Malcolm Arnold deserves a celebration (Arts, Mar 6). Laurence Olivier, a very close friend, used to console William by saying: “Just as in the theatre you are seven years in and seven years out; if you live long enough, you will again hear your music played.” I am glad to say that William lived longer than Sir William Glock. Lady Walton Isola d'Ischia, Italy Frets the troubled soul Sir – I was chairman of the avant garde, Arts Council-funded New Macnaghtan concerts in 1976 to 1979: Nicholas Kenyon was on the committee (Arts, Mar 6; Letters Mar 10, 11). -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Issam Kourbaj 'Imploded, Burnt, Turned to Ash' Performance

Press Release Issam Kourbaj Imploded, burnt, turned to ash, 2021 Howard Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge Live-streamed drawing and sound performance in collaboration with composer Richard Causton and soprano Jessica Summers Issam Kourbaj, Burning, 2020 15 March 2021, 5pm This performance by the Syrian-born and Cambridge- I will then burn the final drawing and place the based artist Issam Kourbaj marks the tenth anniversary remaining ash in a glass box. This will be exhibited in of the Syrian uprising – a crisis that resulted in violent a sacred space to memorialise every victim of the last armed conflict and ongoing civil war. Kourbaj’s decade, while also being dedicated to all Syrians lost, performance will take place on the 15 March, the first displaced and still suffering from this ongoing crisis. day of the unrest a decade ago. The artist describes his project in his own words below: Towards the end of the performance, the viewer will hear words written by myself, set to music by renowned To mark the tenth anniversary of the Syrian uprising, composer Richard Causton (Faculty of Music, University which was sparked by teenage graffiti in March 2011, of Cambridge) and sung by soprano Jessica Summers. this drawing performance will pay homage to those young people who dared to speak their mind, the masses Issam Kourbaj who protested publicly, as well as the many Syrian eyes that were, in the last ten years, burnt and brutally closed This project is a collaboration between the artist, forever. Kettle’s Yard, The Heong Gallery and The Fitzwilliam Museum (all part of the University of Cambridge). -

The Critical Reception of Tippett's Operas

Between Englishness and Modernism: The Critical Reception of Tippett’s Operas Ivan Hewett (Royal College of Music) [email protected] The relationship between that particular form of national identity and consciousness we term ‘Englishness’ and modernism has been much discussed1. It is my contention in this essay that the critical reception of the operas of Michael Tippett sheds an interesting and revealing light on the relationship at a moment when it was particularly fraught, in the decades following the Second World War. Before approaching that topic, one has to deal first with the thorny and many-sided question as to how and to what extent those operas really do manifest a quality of Englishness. This is more than a parochial question of whether Tippett is a composer whose special significance for listeners and opera-goers in the UK is rooted in qualities that only we on these islands can perceive. It would hardly be judged a triumph for Tippett if that question were answered in the affirmative. On the contrary, it would be perceived as a limiting factor — perhaps the very factor that prevents Tippett from exporting overseas as successfully as his great rival and antipode, Benjamin Britten. But even without that hard evidence of Tippett’s limited appeal, the very idea that his Englishness forms a major part of his significance could in itself be a disabling feature of the music. We are squeamish these days about granting a substantive aesthetic value to music on the grounds of its national qualities, if the composer in question is not safely locked away in the relatively remote past. -

That World of Somewhere in Between: the History of Cabaret and the Cabaret Songs of Richard Pearson Thomas, Volume I

That World of Somewhere In Between: The History of Cabaret and the Cabaret Songs of Richard Pearson Thomas, Volume I D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebecca Mullins Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Scott McCoy, advisor Dr. Graeme Boone Professor Loretta Robinson Copyright by Rebecca Mullins 2013 Abstract Cabaret songs have become a delightful and popular addition to the art song recital, yet there is no concise definition in the lexicon of classical music to explain precisely what cabaret songs are; indeed, they exist, as composer Richard Pearson Thomas says, “in that world that’s somewhere in between” other genres. So what exactly makes a cabaret song a cabaret song? This document will explore the topic first by tracing historical antecedents to and the evolution of artistic cabaret from its inception in Paris at the end of the 19th century, subsequent flourish throughout Europe, and progression into the United States. This document then aims to provide a stylistic analysis to the first volume of the cabaret songs of American composer Richard Pearson Thomas. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to the person who has been most greatly impacted by its writing, however unknowingly—my son Jack. I hope you grow up to be as proud of your mom as she is of you, and remember that the things in life most worth having are the things for which we must work the hardest. -

Two Serial Pieces Written in 1968 by Pierre Boulez and Isang Yun By

A Study of Domaines and Riul: Two Serial Pieces Written in 1968 by Pierre Boulez and Isang Yun by Jinkyu Kim Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Julian L. Hook, Research Director _______________________________________ James Campbell, Chair _______________________________________ Eli Eban _______________________________________ Kathryn Lukas April 10, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Jinkyu Kim iii To Youn iv Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. v List of Examples ............................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ix List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. xi Chapter 1: MUSICAL LANGUAGES AFTER WORLD WAR II ................................................ 1 Chapter 2: BOULEZ, DOMAINES ................................................................................................ -

Microkorg Owner's Manual

E 1 ii Precautions Data handling Location THE FCC REGULATION WARNING (for U.S.A.) Unexpected malfunctions can result in the loss of memory Using the unit in the following locations can result in a This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the contents. Please be sure to save important data on an external malfunction. limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the data filer (storage device). Korg cannot accept any responsibility • In direct sunlight FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable for any loss or damage which you may incur as a result of data • Locations of extreme temperature or humidity protection against harmful interference in a residential loss. • Excessively dusty or dirty locations installation. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate • Locations of excessive vibration radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in • Close to magnetic fields accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no Printing conventions in this manual Power supply guarantee that interference will not occur in a particular Please connect the designated AC adapter to an AC outlet of installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference Knobs and keys printed in BOLD TYPE. the correct voltage. Do not connect it to an AC outlet of to radio or television reception, which can be determined by Knobs and keys on the panel of the microKORG are printed in voltage other than that for which your unit is intended. turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to BOLD TYPE. -

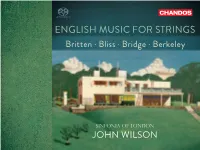

ENGLISH MUSIC for STRINGS Britten • Bliss • Bridge • Berkeley

SUPER AUDIO CD ENGLISH MUSIC FOR STRINGS Britten • Bliss • Bridge • Berkeley Sinfonia of London JOHN WILSON Hampstead, mid-1930s piano,athomeEastHeathLodge, Blüthner Bliss,athislatemother’s Arthur Photographer unknown / Courtesy of the Bliss Collection, with thanks to the late Trudy Bliss English Music for Strings Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, Op. 10 (1937) 23:37 for String Orchestra To F.B. A tribute with affection and admiration 1 Introduction and Theme. Lento maestoso – Allegretto poco lento – 1:31 2 Adagio. Adagio – 1:52 3 March. Presto alla marcia – 1:05 4 Romance. Allegretto grazioso – 1:31 5 Aria Italiana. Allegro brillante – 1:11 6 Bourrée Classique. Allegro e pesante – 1:17 7 Wiener Walzer. Lento – Vivace – Lento – Vivace – [ ] – Vivace – Lento – Tempo I – Lento – Tempo I – Lento – Tempo vivace – 2:05 8 Moto Perpetuo. Allegro molto – 1:00 9 Funeral March. Andante ritmico – Con moto – 3:49 10 Chant. Lento – 1:39 11 Fugue and Finale. Allegro molto vivace – Molto animato – Lento e solenne – Poco comodo e tranquillo – Lento – Più presto 6:34 3 Frank Bridge (1879 – 1941) 12 Lament, H 117 (1915) 3:47 for String Orchestra Catherine, aged 9, ‘Lusitania’ 1915 Adagio, con molto espressione – Poco più adagio Sir Lennox Berkeley (1903 – 1989) Serenade for Strings, Op. 12 (1938 – 39) 13:01 in Four Movements To John and Clement Davenport 13 I Vivace 2:09 14 II Andantino 3:52 15 III Allegro moderato 3:11 16 IV Lento 3:48 4 Sir Arthur Bliss (1891 – 1975) Music for Strings, F 123 (1935) 23:56 Dedicated