Art About Life Form Encounters: Making Sense of Place in the Okanagan Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015)

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015) By Richard Henderson Research Ecologist, WI DNR Bureau of Science Services Summary This is a preliminary list of insects that are either well known, or likely, to be closely associated with Wisconsin’s original native prairie. These species are mostly dependent upon remnants of original prairie, or plantings/restorations of prairie where their hosts have been re-established (see discussion below), and thus are rarely found outside of these settings. The list also includes some species tied to native ecosystems that grade into prairie, such as savannas, sand barrens, fens, sedge meadow, and shallow marsh. The list is annotated with known host(s) of each insect, and the likelihood of its presence in the state (see key at end of list for specifics). This working list is a byproduct of a prairie invertebrate study I coordinated from1995-2005 that covered 6 Midwestern states and included 14 cooperators. The project surveyed insects on prairie remnants and investigated the effects of fire on those insects. It was funded in part by a series of grants from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. So far, the list has 475 species. However, this is a partial list at best, representing approximately only ¼ of the prairie-specialist insects likely present in the region (see discussion below). Significant input to this list is needed, as there are major taxa groups missing or greatly under represented. Such absence is not necessarily due to few or no prairie-specialists in those groups, but due more to lack of knowledge about life histories (at least published knowledge), unsettled taxonomy, and lack of taxonomic specialists currently working in those groups. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth Meeting of the Canadian Forest Genetics Association

PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SIXTH MEETING OF THE CANADIAN FOREST GENETICS ASSOCIATION PART 1 Minutes and Member’s Reports PART 2 Symposium Applied Forest Genetics – Where do we want to be in 2049? Génétique forestière appliquée - où voulons-nous être en 2049? COMPTES RENDUS DU TRENTE-SIXIÈME CONGRÈS DE L’ASSOCIATION CANADIENNE DE GÉNÉTIQUE FORESTIÈRE 1re PARTIE Procès-verbaux et rapports des membres 2e PARTIE Colloque National Library of Canada cataloguing in publication data Canadian Forest Genetics Association. Meeting (36th : 2019 : Lac Delage, QC) Proceedings of the Thirty-sixth Meeting of the Canadian Forest Genetics Association Includes preliminary text and articles in French. Contents: Part 1 Minutes and Member's Reports. Part 2 Symposium CODE TO BE DETERMINED CODE TO BE DETERMINED 1 Forest genetics – Congresses. 2 Trees – Breeding – Congresses. 3 Forest genetics – Canada – Congresses. I Atlantic Forestry Centre II Title: Applied Forest Genetics – Where do we want to be in 2049? III Title: Proceedings of the Thirty-sixth Meeting of the Canadian Forest Genetics Association Données de catalogage avant publication de la Bibliothèque nationale du Canada L'Association canadienne de génétique forestière. Conférence (36e : 2019 : Lac Delage, QC) Comptes rendus du trente-sixième congrès de l'Association canadienne de génétique forestière Comprend des textes préliminaires et des articles en français. Sommaire : 1re partie Procès-verbaux et rapports des membres. 2e partie Colloque CODAGE CODAGE 1 Génétiques forestières – Congrès. 2 Arbres – Amélioration – Congrès. 3 Génétiques forestières – Canada – Congrès. I Centre de foresterie de l’Atlantique II Titre : Génétique forestière appliquée - où voulons-nous être en 2049? III Titre : Comptes rendus du trente-sixième congrès de l'Association canadienne de génétique forestière PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SIXTH MEETING OF THE CANADIAN FOREST GENETICS ASSOCIATION PART 1 Minutes and members’ reports Lac Delage, Quebec August 19 – 23, 2019 Editors D.A. -

Coleoptera: Carabidae

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Acta Entomologica Slovenica Jahr/Year: 2004 Band/Volume: 12 Autor(en)/Author(s): Polak Slavko Artikel/Article: Cenoses and species phenology of Carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in three stages of vegetational successions on upper Pivka karst (SW Slovenia) Cenoze in fenologija vrst kresicev (Coleoptera: Carabidae) v treh stadijih zarazcanja krasa na zgornji Pivki (JZ Slovenija) 57-72 ©Slovenian Entomological Society, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at LJUBLJANA, JUNE 2004 Vol. 12, No. 1: 57-72 XVII. SIEEC, Radenci, 2001 CENOSES AND SPECIES PHENOLOGY OF CARABID BEETLES (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) IN THREE STAGES OF VEGETATIONAL SUCCESSION IN UPPER PIVKA KARST (SW SLOVENIA) Slavko POLAK Notranjski muzej Postojna, Ljubljanska 10, SI-6230 Postojna, Slovenia, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract - The Carabid beetle cenoses in three stages of vegetational succession in selected karst area were studied. Year-round phenology of all species present is pre sented. Species richness of the habitats, total number of individuals trapped and the nature conservation aspects of the vegetational succession of the karst grasslands are discussed. K e y w o r d s : Coleoptera, Carabidae, cenose, phenology, vegetational succession, karst Izvleček CENOZE IN FENOLOGIJA VRST KREŠIČEV (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) V TREH STADIJIH ZARAŠČANJA KRASA NA ZGORNJI PIVKI (JZ SLOVENIJA) Raziskali smo cenoze hroščev krešičev -

Household Insects of the Rocky Mountain States

Household Insects of the Rocky Mountain States Bulletin 557A January 1994 Colorado State University, University of Wyoming, Montana State University Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Milan Rewerts, interim director of Cooperative Extension, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado. Cooperative Extension programs are available to all without discrimination. No endorsement of products named is intended nor is criticism implied of products not mentioned. FOREWORD This publication provides information on the identification, general biology and management of insects associated with homes in the Rocky Mountain/High Plains region. Records from Colorado, Wyoming and Montana were used as primary reference for the species to include. Mention of more specific localities (e.g., extreme southwestern Colorado, Front Range) is provided when the insects show more restricted distribution. Line drawings are provided to assist in identification. In addition, there are several lists based on habits (e.g., flying), size, and distribution in the home. These are found in tables and appendices throughout this manual. Control strategies are the choice of the home dweller. Often simple practices can be effective, once the biology and habits of the insect are understood. Many of the insects found in homes are merely casual invaders that do not reproduce nor pose a threat to humans, stored food or furnishings. These may often originate from conditions that exist outside the dwelling. Other insects found in homes may be controlled by sanitation and household maintenance, such as altering potential breeding areas (e.g., leaky faucets, spilled food, effective screening). -

PP Elm Seed Bug, Arocatus Melanocephalus: an Exotic Invasive

Elm seed bug, Arocatus melanocephalus: an exotic invasive pest new to the U.S. Idaho State Department of Agriculture In summer 2012, the elm seed bug (ESB), an invasive insect new to the U.S., was first identified from specimens collected in Ada and Canyon counties in Idaho. During 2013 it was found to have spread to Elmore, Gem, Owyhee, Payette, and Washington counties as well as Malheur County, Oregon. Commonly distributed in south-central Europe, ESB feeds primarily on the seeds of elm trees, although they have also been collected from oak and linden trees in Europe. The insect does not damage trees or buildings, nor does it present any threat to human health. However, due to its habit of entering houses and other buildings in large numbers to escape the summer heat and later to Adult elm seed bugs overwinter, it can be a significant nuisance to ISDA photo homeowners. Elm seed bug biology Elm seed bugs spend the winter as hibernating adults, mate during the spring and lay eggs on elm trees. Immature ESB feed on elm seeds from May through June becoming adults by early summer. Elm seed bugs are most noticeable in springtime as overwintering ESB begin to emerge inside buildings and try to escape, during hot periods in the summer when ESB attempt to enter buildings to get away from the heat, and in the autumn when they enter buildings to overwinter. When disturbed or crushed, the bugs produce Current reported range of Elm Seed Bug in the US an unpleasant odor. Map from USDA APHIS PPQ PP Photos courtesy of Charles Olsen, USDA APHIS PPQ – Bugwood.org Identification Elm seed bug belongs to the order Hemiptera (the “true bugs”) and is related to the boxelder bug and stink bug. -

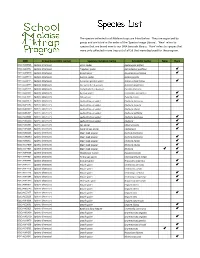

Species List

The species collected in all Malaise traps are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. ‘New’ refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in one trap out of all 59 that were deployed for the program. -

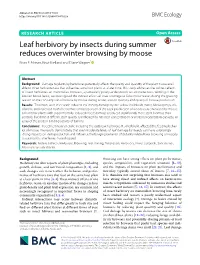

Leaf Herbivory by Insects During Summer Reduces Overwinter Browsing by Moose Brian P

Allman et al. BMC Ecol (2018) 18:38 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0192-x BMC Ecology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Leaf herbivory by insects during summer reduces overwinter browsing by moose Brian P. Allman, Knut Kielland and Diane Wagner* Abstract Background: Damage to plants by herbivores potentially afects the quality and quantity of the plant tissue avail- able to other herbivore taxa that utilize the same host plants at a later time. This study addresses the indirect efects of insect herbivores on mammalian browsers, a particularly poorly-understood class of interactions. Working in the Alaskan boreal forest, we investigated the indirect efects of insect damage to Salix interior leaves during the growing season on the consumption of browse by moose during winter, and on quantity and quality of browse production. Results: Treatment with insecticide reduced leaf mining damage by the willow leaf blotch miner, Micrurapteryx sali- cifoliella, and increased both the biomass and proportion of the total production of woody tissue browsed by moose. Salix interior plants with experimentally-reduced insect damage produced signifcantly more stem biomass than controls, but did not difer in stem quality as indicated by nitrogen concentration or protein precipitation capacity, an assay of the protein-binding activity of tannins. Conclusions: Insect herbivory on Salix, including the outbreak herbivore M. salicifoliella, afected the feeding behav- ior of moose. The results demonstrate that even moderate levels of leaf damage by insects can have surprisingly strong impacts on stem production and infuence the foraging behavior of distantly related taxa browsing on woody tissue months after leaves have dropped. -

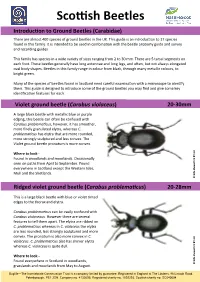

Scottish Beetles Introduction to Ground Beetles (Carabidae) There Are Almost 400 Species of Ground Beetles in the UK

Scottish Beetles Introduction to Ground Beetles (Carabidae) There are almost 400 species of ground beetles in the UK. This guide is an introduction to 17 species found in this family. It is intended to be used in combination with the beetle anatomy guide and survey and recording guides. This family has species in a wide variety of sizes ranging from 2 to 30 mm. There are 5 tarsal segments on each foot. These beetles generally have long antennae and long legs, and often, but not always elongated oval body shapes. Beetles in this family range in colour from black, through many metallic colours, to bright green. Many of the species of beetles found in Scotland need careful examination with a microscope to identify them. This guide is designed to introduce some of the ground beetles you may find and give some key identification features for each. Violet ground beetle (Carabus violaceus) 20-30mm A large black beetle with metallic blue or purple edging, this beetle can often be confused with Carabus problematicus, however, it has smoother, more finely granulated elytra, whereas C. problematicus has elytra that are more rounded, more strongly sculptured and less convex. The Violet ground beetle pronotum is more convex. Where to look - Found in woodlands and moorlands. Occasionally seen on paths from April to September. Found everywhere in Scotland except the Western Isles, Mull and the Shetlands. BY 2.0 CC Shcmidt © Udo Ridged violet ground beetle (Carabus problematicus) 20-28mm This is a large black beetle with blue or violet tinted edges to the thorax and elytra. -

A Systematic Study of the Family Rhynchitidae of Japan(Coleoptera

Humans and Nature. No. 2, 1 ―93, March 1993 A Systematic Study of the Family Rhynchitidae of Japan (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) * Yoshihisa Sawada Division of Phylogenetics, Museum of Nature and Human Activities, Hyogo, Yayoi~ga~oka 6, Sanda, 669~ 13 fapan Abstract Japanese RHYNCHITIDAE are systematically reviewed and revised. Four tribes, 17 genera and 62 species are recognized. Original and additional descriptions are given, with illustrations of and keys to their taxa. The generic and subgeneric names of Voss' system are reviewed from the viewpoint of nomenclature. At the species level, 12 new species Auletobius planifrons, Notocyrtus caeligenus, Involvulus flavus, I. subtilis, I. comix, I. aes, I. lupulus, Deporaus tigris, D. insularis, D. eumegacephalus, D. septemtrionalis and D. rhynchitoides are described and 1 species Engnamptus sauteri are newly recorded from Japan. Six species and subspecies names Auletes carvus, A. testaceus and A. irkutensis japonicus, Auletobius okinatuaensis, Aderorhinus pedicellaris nigricollis and Rhynchites cupreus purpuleoviolaceus are synonymized under Auletobius puberulus, A. jumigatus, A. uniformis, Ad. crioceroides and I. cylindricollis, respectively. One new name Deporaus vossi is given as the replacement name of the primally junior homonym D. pallidiventris Voss, 1957 (nec Voss, 1924). Generic and subgeneric classification is revised in the following points. The genus Notocyrtus is revived as an independent genus including subgenera Notocyrtus s. str., Exochorrhynchites and Heterorhynchites. Clinorhynckites and Habrorhynchites are newly treated as each independent genera. Caenorhinus is newly treated as a valid subgenus of the genus Deporaus. The genera Neocoenorrhinus and Piazorhynckites are newly synonymized under Notocyrtus and Agilaus, respectively, in generic and subgeneric rank. A subgeneric name, Aphlorhynehites subgen. -

Eriophyoid Mite Fauna (Acari: Trombidiformes: Eriophyoidea) of Turkey: New Species, New Distribution Reports and an Updated Catalogue

Zootaxa 3991 (1): 001–063 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3991.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:AA47708E-6E3E-41D5-9DC3-E9D77EAB9C9E ZOOTAXA 3991 Eriophyoid mite fauna (Acari: Trombidiformes: Eriophyoidea) of Turkey: new species, new distribution reports and an updated catalogue EVSEL DENIZHAN1, ROSITA MONFREDA2, ENRICO DE LILLO2,4 & SULTAN ÇOBANOĞLU3 1Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Yüzüncü Yıl, Van, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Soil, Plant and Food Sciences (Di.S.S.P.A.), section of Entomology and Zoology, University of Bari Aldo Moro, via Amendola, 165/A, I–70126 Bari, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 3Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Ankara, Dıskapı, 06110 Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by D. Knihinicki: 21 May 2015; published: 29 Jul. 2015 EVSEL DENIZHAN, ROSITA MONFREDA, ENRICO DE LILLO & SULTAN ÇOBANOĞLU Eriophyoid mite fauna (Acari: Trombidiformes: Eriophyoidea) of Turkey: new species, new distribution reports and an updated catalogue (Zootaxa 3991) 63 pp.; 30 cm. 29 Jul. 2015 ISBN 978-1-77557-751-5 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-752-2 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2015 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2015 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. -

Traits in the Light of Ecology and Conservation of Ground Beetles

Traits in the light of ecology and conservation of ground beetles Von der Fakultät Nachhaltigkeit der Leuphana Universität Lüneburg zur Erlangung des Grades Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften - Dr. rer. nat. – genehmigte Dissertation von Dorothea Irmgard Ilse Nolte geb. Ehlers am 18.07.1987 in Bielefeld 2018 Eingereicht am: 09. November 2018 Mündliche Verteidigung am: 25. September 2019 Erstbetreuer und Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Thorsten Assmann Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Tamar Dayan Drittgutachter: Prof. Dr. Pietro Brandmayr Die einzelnen Beiträge des kumulativen Dissertationsvorhabens sind oder werden ggf. inkl. des Rahmenpa- piers wie folgt veröffentlicht: Nolte, D., Boutaud, E., Kotze, D. J., Schuldt, A., and Assmann, T. (2019). Habitat specialization, distribution range size and body size drive extinction risk in carabid beetles. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28, 1267-1283. Nolte, D., Schuldt, A., Gossner, M.M., Ulrich, W. and Assmann, T. (2017). Functional traits drive ground beetle community structures in Central European forests: Implications for conservation. Biological Conservation, 213, 5–12. Homburg, K., Drees, C., Boutaud, E., Nolte, D., Schuett, W., Zumstein, P., von Ruschkowski, E. and Assmann, T. (2019). Where have all the beetles gone? Long-term study reveals carabid species decline in a nature reserve in Northern Germany. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 12, 268-277. Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019 "Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better." - Albert Einstein Nature awakens a great fascination in all of us and gives us a feeling of balance and peace of mind. Wherever you look, there is always something to discover. The plethora of habitats, species and various adaptation strategies is the true secret of nature’s success.