Seeking the Rule of Law in the Absence of the State: Transitional Justice and Policing in Opposition-Controlled Syria Pt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Epidemiological Findings of Major Chemical Attacks in the Syrian War Are Consistent with Civilian Targeting: a Short Report Jose M

Rodriguez-Llanes et al. Conflict and Health (2018) 12:16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0150-4 SHORTREPORT Open Access Epidemiological findings of major chemical attacks in the Syrian war are consistent with civilian targeting: a short report Jose M. Rodriguez-Llanes1, Debarati Guha-Sapir2 , Benjamin-Samuel Schlüter2 and Madelyn Hsiao-Rei Hicks3* Abstract Evidence of use of toxic gas chemical weapons in the Syrian war has been reported by governmental and non-governmental international organizations since the war started in March 2011. To date, the profiles of victims of the largest chemical attacks in Syria remain unknown. In this study, we used descriptive epidemiological analysis to describe demographic characteristics of victims of the largest chemical weapons attacks in the Syrian war. We analysed conflict-related, direct deaths from chemical weapons recorded in non-government-controlled areas by the Violation Documentation Center, occurring from March 18, 2011 to April 10, 2017, with complete information on the victim’s date and place of death, cause and demographic group. ‘Major’ chemical weapons events were defined as events causing ten or more direct deaths. As of April 10, 2017, a total of 1206 direct deaths meeting inclusion criteria were recorded in the dataset from all chemical weapons attacks regardless of size. Five major chemical weapons attacks caused 1084 of these documented deaths. Civilians comprised the majority (n = 1058, 97.6%) of direct deaths from major chemical weapons attacks in Syria and combatants comprised a minority of 2.4% (n = 26). In the first three major chemical weapons attacks, which occurred in 2013, children comprised 13%–14% of direct deaths, ranging in numbers from 2 deaths among 14 to 117 deaths among 923. -

Syrian Voices Art – Theory for Syria by Róza El-Hassan Bloody Peace By

Syrian Voices Art – Theory for Syria By Róza El-Hassan Bloody Peace By Shadi Alshhadeh Varvara Stepanova ‘Future is our only goal’, 1921 by Ben Vautier,artist born 1936 Ben Vautier •Kartoneh from Deir El Zor •Turn right and after one kilometer you arrive to the city of Deir •El Zor. +18 is for graphic scenes Kartoneh fro Deir EL Zor, Syria Halfaya, justice will be inflour- December 23 Dayer Elzour. our crave,weather its ade of dust or flour december 23 Deir El Zor because they deserve life - the week of demanding detained people from Syrians prisons Halfaya, justice will be inflour- December 23 Dayer Elzour. our crave,weather its ade of dust or flour december 23 Deir El Zor Dayer Elzour will remain a sign of difference in the world of pommegrate Kartoneh from Deir El Zor, Kartoon pain, 2013 Pigeon by anonymous photographer Lens Binnishi, Binnish city, Northern Syria, Idlib Region 2013 The word “Steadfast” in Arabic, collective body-art action, Binnish city, Northern Syria , From website: Coordinators of the revolution in the city of Binnish 2012 Liberty Statue made in Homs, 2012 Sculpturer makes objects of empty rocket shells and bullets http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jP_takNr-as Grafitty by Crazy Nano, Daraa, Southern Syria, 2012 Faculty of Art, lecture room in Aleppo University after the massacre caused by rocket in January 2013 Flash-mob – sit in protest action by students at Damascus university in solidarity with the sieged cities, beginning of 2012 Ali Ferzat, Syrian Caricaturist, January 2013 Four Brides of Peace, Damascus. Autumn 2012 - Arrested during the action and released after 48 days. -

Security Council Distr.: General 24 August 2016

United Nations S/2016/738/Rev.1 Security Council Distr.: General 24 August 2016 Original: English Letter dated 24 August 2016 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the third report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism. I should be grateful if the present letter and the report could be brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 16-14878 (E) 140916 *1614878* S/2016/738/Rev.1 Letter dated 24 August 2016 from the Leadership Panel of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons- United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism addressed to the Secretary-General The Leadership Panel of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism has the honour to transmit the Mechanism’s third report pursuant to Security Council resolution 2235 (2015). The report provides an update on the activities of the Mechanism up to 19 August 2016. It also outlines the concluding assessments of the Leadership Panel to date, on the basis of the results of the investigation into the nine selected cases of the use of chemicals as weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic. The Leadership Panel wishes to thank the Secretary-General for the confidence placed in it. The Panel appreciates the indispensable support provided by the Secretariat, including the Office for Disarmament Affairs, the Department for Political Affairs and the Office of Legal Affairs, and the United Nations officials who have assisted the Mechanism in New York, Geneva and Damascus. -

Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria

A NEW NORMAL Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria February 2016 SYRIAN AMERICAN MEDICAL SOCIETY C1 Above: Bab Al Hawa Hospital, Idlib, April 21, 2014. On the cover, top: Bab Al Hawa Hospital, Idlib, April 21, 2014; bottom: Binnish, Idlib, March 23, 2015. ABOUT THE SYRIAN AMERICAN MEDICAL SOCIETY The Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) is a non-profit, non-political, professional and medical relief orga- nization that provides humanitarian assistance to Syrians in need and represents thousands of Syrian American medical professionals in the United States. Founded in 1998 as a professional society, SAMS has evolved to meet the growing needs and challenges of the medical crisis in Syria. Today, SAMS works on the front lines of crisis relief in Syria and neighboring countries to serve the medical needs of millions of Syrians, support doctors and medical professionals, and rebuild healthcare. From establishing field hospitals and training Syrian physicians to advocating at the highest levels of government, SAMS is working to alleviate suffering and save lives. Design: Sensical Design & Communication C2 A NEW NORMAL: Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria Acknowledgements New Normal: Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria was written by Kathleen Fallon, Advocacy Manager of the Syrian Amer- A ican Medical Society (SAMS); Natasha Kieval, Advocacy Associate of SAMS; Dr. Zaher Sahloul, Senior Advisor and Past President of SAMS; and Dr. Houssam Alnahhas of the Union of Medical Care and Relief Or- ganizations (UOSSM), in partnership with many SAMS colleagues and partners who provided insight and feedback. Thanks to Laura Merriman, Advocacy Intern of SAMS, for her research and contribution to the report’s production. -

UK Home Office

Country Policy and Information Note Syria: the Syrian Civil War Version 4.0 August 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

“Targeting Life in Idlib”

HUMAN RIGHTS “Targeting Life in Idlib” WATCH Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Map .................................................................................................................................. i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

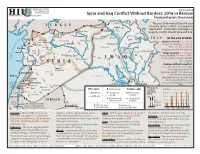

Syria and Iraq Conflict Without Borders: 2016 in Review

U.S. Department of State [email protected] Unclassified http://hiu.state.gov Syria and Iraq Conflict Without Borders: 2016 in Review HUMANITARIAN INFORMATION UNIT Humanitarian Overview Dahuk The year 2016 marked the fifth year TURKEY since the Syrian conflict crisis began in Al Qamishli Dahuk March 2011. In late 2013, ISIS began to Ra’s al ‘Ayn Rabi‘ah wage its conflict in both Syria and Iraq. ‘Ayn al ‘Arab Al Hasakah Sinjar Erbil (Kobane) Mosul a Reyhanlı IRAN At the end of 2016: e Aleppo Erbil S Ar Raqqah Al Hasakah Urum al Kubra Syrians in need: 13.5 million n Ar Raqqah Al Qayyarah a Al Fu‘ah in Syria, including 6.3 million e Idlib n E Ninawa IDPs. 4.8 million Syrian Aleppo up a Kafriyah h Kirkuk r r refugees outside the country. r a Idlib te As Sulaymaniyah e Latakia s t Latakia Kirkuk Iraqis in need: 11 million in i d Dayr az Zawr Iraq, including 3.1 million IDPs. e Hamah M Tartus Dayr az Zawr IRAQ 293,000 Iraqi refugees outside Tartus T the country. ig SYRIA r is Civilians killed in conflict: Homs 16,913 Syrians and 6,878 Iraqis Tadmur Salah ad Din (Palmyra) were reported killed in LEBANON Homs fighting in 2016. This does not Diyala include the estimated Beirut Al Anbar thousands more who died of Az Zabadani Al Fallujah Euphr disease, malnutrition, and Madaya Hit ates GOLAN Damascus exposure due to the conflict. HEIGHTS Darayya Ar Ramadi Baghdad (Israeli- Damascus Rukban occupied) Damascus Persons in IDP locations Border crossing NationalBaghdad capital 15 million Al Countryside needWasit of Qunaytirah Dar‘a As aid since 12 Syrian IDP site UN aid border International 2012 Suwayda‘ crossing boundary Babil ISRAEL Iraqi IDP camp Syria Iraq 9 Besieged areas in KarbalaAdministrative JORDAN Syria in 2016 (UN) boundary Not 6 West displaced Bank* *Israeli-occupied with current status 3 subject to Israeli-Palestinian Interim 0 50 km Hard to reach areas Restricted access Displaced Maysan Amman Agreement; permanent status to be determined through further negotiations. -

Local Intermediaries in Post-2011 Syria Transformation and Continuity Local Intermediaries in Post-2011 Syria Transformation and Continuity

Local Intermediaries in post-2011 Syria Transformation and Continuity Local Intermediaries in post-2011 Syria Transformation and Continuity Edited by Kheder Khaddour and Kevin Mazur Contributors: Armenak Tokmajyan Ayman Al-Dassouky Hadeel Al-Saidawi Roger Asfar Sana Fadel Published in June 2019 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung P.O. Box 116107 Riad El Solh Beirut 1107 2210 Lebanon This publication is the product of a capacity building project for Syrian researchers that was designed and implemented by Kheder Khaddour and Kevin Mazur. Each participant conducted independent research and authored a paper under the editors’ supervision. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be printed, reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Layout and Cover Design: Milad Amin Translation and Editing: Hannah Massih, Livia Bergmeijer, Niamh Fleming- Farrell, Rana Sa’adah and Yaaser Azzayyat CONTENTS Building from the Wreckage Intermediaries in Contemporary Syria........................................................4 Kheder Khaddour and Kevin Mazur Politics of Rural Notables...........................................................................21 Armenak Tokmajyan What We Can Learn from the Rise of Local Traders in Syria........................43 Ayman Al-Dassouky Informal State-Society Relations and Family Networks in Rural Idlib..........67 Hadeel Al-Saidawi The Role of the Christian Clergy in Aleppo as Mediators The Nature of Relationships and their Attributes.......................................93 Roger Asfar The Leaders of Damascus The Intermediary Activists in the 2011 Uprising.........................................119 Sana Fadel Building from the Wreckage Intermediaries in Contemporary Syria Kheder Khaddour and Kevin Mazur Seven years of war in Syria have shattered many of the social and political relations that existed before the conflict. -

Testimony of Mohamed Tennari, MD Idlib Coordinator Syrian American

Testimony of Mohamed Tennari, MD Idlib Coordinator Syrian American Medical Society House Committee on Foreign Affairs The Continued Use of Chemical Weapons by the Assad Regime June 17, 2015 Translators used to help prepare written statement: Kathleen Fallon and Jihad Alharash Translator at hearing: Mouaz Moustafa Chairman Royce, Ranking Member Engel, and members of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs: on behalf of the Syrian American Medical Society and the people of Syria, thank you for organizing this important hearing. I have traveled from the province of Idlib in northern Syria in order to testify before you about the chemical attacks I have witnessed in my community. I am the medical director of a field hospital in my hometown of Sarmin, Idlib. I am also the Idlib Coordinator for the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS). SAMS is a nonpolitical, medical relief organization that supports Syrian doctors, sponsors hospitals, and provides medical and humanitarian assistance inside of Syria. Last year alone, SAMS reached over 1.4 million Syrians through its medical work and operated 95 medical facilities in Syria, including my hospital in Sarmin. I am a radiologist by training, but since the conflict in Syria began, I have been working in general emergency medicine to help trauma victims affected by the daily bombings and attacks. I helped to establish the field hospital in Sarmin four years ago, after the conflict in Syria began. We are currently using the fourth building to house the field hospital – the first two were flattened to the ground. The government in Syria systematically targets hospitals and ambulances in non-government controlled areas; our field hospital, which operates under the principle of medical neutrality, has been hit by government air attacks 17 times. -

Idlib and Its Environs Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout REUTERS/KHALIL ASHAWI REUTERS/KHALIL

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ FEBRUARY 2020 ■ PN75 Idlib and Its Environs Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout REUTERS/KHALIL ASHAWI REUTERS/KHALIL By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi Greater Idlib and its immediate surroundings in northwest Syria—consisting of rural northern Latakia, north- western Hama, and western Aleppo—stand out as the last segment of the country held by independent groups. These groups are primarily jihadist, Islamist, and Salafi in orientation. Other areas have returned to Syrian government control, are held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), or are held by insurgent groups that are entirely constrained by their foreign backers; that is, these backers effectively make decisions for the insurgents. As for insurgents in this third category, the two zones of particular interest are (1) the al-Tanf pocket, held by the U.S.-backed Jaish Maghaweer al-Thawra, and (2) the areas along the northern border with Turkey, from Afrin in the west to Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain in the east, controlled by “Syrian © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. AYMENN JAWAD AL-TAMIMI National Army” (SNA) factions that are backed by in Idlib province that remained outside insurgent control Turkey and cannot act without its approval. were the isolated Shia villages of al-Fua and Kafarya, This paper considers the development of Idlib and whose local fighters were bolstered by a small presence its environs into Syria’s last independent center for insur- of Lebanese Hezbollah personnel serving in a training gents, beginning with the province’s near-full takeover by and advisory capacity.3 the Jaish al-Fatah alliance in spring 2015 and concluding Charles Lister has pointed out that the insurgent suc- at the end of 2019, by which time Jaish al-Fatah had cesses in Idlib involved coordination among the various long ceased to exist and the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir rebel factions in the northwest.