Robert Gerhard and His Music 2000 the ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compota De Cobla Dossier Didàctic Índex

Compota de Cobla Dossier didàctic Índex 2 Presentació 3 Fitxa artística 4 Objectius i suggeriments didàctics 5,6 Material específic pel treball del concert 7,8 Breus apunts sobre la història de la cobla 9 a 15 Instrumentació 16,17 Discografía 18 Bibliografia i enllaços a Internet 1 Presentació La cobla és una de les formacions instrumentals més representatives de la música tradicional i popular catalana. D´entre els instruments que la configuren trobem instruments tant antics com el flabiol i tant peculiars com el tible o la tenora. El concert que us oferim vol ser una aproximació a aquesta agrupació instrumental. Presentar els diferents instruments, la seva constitució i possibilitats sonores i parlar de la història de la música popular catalana són alguns dels propòsits d´aquest espectacle. El conte “Compota de cobla” ens donarà la possibilitat d´escoltar els instruments per separat i gaudir del so de la cobla. A més a més, comptem amb una de les cobles de més prestigi del nostre país que seran els encar- regats de fer-nos passar una bona estona de concert: la Cobla Sant Jordi- Ciutat de Barcelona. Així doncs, esperem que el present dossier sigui d´interès. Us recomanem que el fullegeu amb temps i cura. 2 Fitxa artística COBLA SANT JORDI-CIUTAT DE BARCELONA Guió, coordinació i direcció artística: La Botzina Enric Ortí: tenora Josep Antoni Sánchez: tenora Presentador: Toni Cuesta Conte: Joana Moreno i Toni Cuesta Música del conte: Jordi Badia Producció: Cobla Sant Jordi-Ciutat de Barcelona i La Botzina WWW.coblasantjordi.cat 3 Objectius En el disseny de la present proposta de concert vàrem creure necessari assolir els següents objectius didàc tics: - Oferir música en directe a través d´una formació instrumental de mitjà format ( 11 músics) - Procurar que els oients s´ho passin bé gaudint d´un concert d´aquestes carecterístiques - Iniciar en el coneixement dels diferents instruments que formen part d´una cobla, escoltar el seu so i conèixer les característiques més destacables. -

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

Talan Literature

TALAN LITERATURE: ANTONI TAPIES. PAPERS GRlSOS CREUATS. 1977. STEPHEN WlRTZ GALLERY COLLECTION. SAN FRANCISCO TRANSLATIONSOF CATALANLITERATURE HAVE MADE PROGRESS IN MANY DIFFERENT SPHERES. CATALAN LITERARY WORKS HAVE STIRRED THE CURIOSITY OF PUBLISHERS ALL OVER THE WORLD WHO HAVE HAD THEM TRANSLATED INTO THEIR OWN LANGUAGE. ORIOL PI DE CABANYES DIRECTOR OF THE INSTITUCIÓ DE LES LLETRES CATALANES CATALONIA 1 DOSSIER XAVIER CORBER~.AUTUMN BOAT SING. 1 982 t's now a long time since those the theatre, it is one of the artistic prac- places their work within the broader years when the presence of Cat- tices in which the social use of the Cata- parameters of the world as a whole. ralan literature in the country's lan language has advanced conside- Frorn 1939 until only a short time ago, bookshops was almost an act of nation- rably. Now that the period of resistance only the dedicated enthusiasrn of Cata- al affirrnation. The persecution of Cat- is well behind us, now that Catalan has ' lan-lovers al1 over the world, usually alan meant that cornpared to other lit- recovered the official status that had linked to universities and teaching, erature few titles were published in our been denied it and has been able to made the publication of Catalan literary language and few outlets were avail- develop unfettered, the challenge of works outside our country possible. To- able to them. The sixties marked the turn- our days is to consolidate the home day, a Copernican revolution has taken ing point in this trend and frorn that market and make sure that Catalan lit- place and Catalan literary works have mornent on Catalan publishing grew in erature finds a permanent place on the stirred the curiosity of publishers al1 a geornetrical progression. -

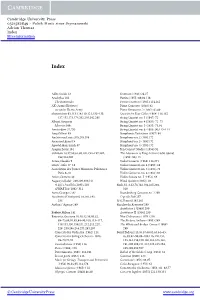

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

¿Granados No Es Un Gran Maestro? Análisis Del Discurso Historiográfico Sobre El Compositor Y El Canon Nacionalista Español

¿Granados no es un gran maestro? Análisis del discurso historiográfico sobre el compositor y el canon nacionalista español MIRIAM PERANDONES Universidad de Oviedo Resumen Enrique Granados (1867-1916) es uno de los tres compositores que conforman el canon del Nacionalismo español junto a Manuel de Falla (1876- 1946) e Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) y, sin embargo, este músico suele quedar a la sombra de sus compatriotas en los discursos históricos. Además, Granados también está fuera del “trío fundacional” del Nacionalismo formado por Felip Pedrell (1841-1922) —considerado el maestro de los tres compositores nacionalistas, y, en consecuencia, el “padre” del nacionalismo español—Albéniz y Falla. En consecuencia, uno de los objetivos de este trabajo es discernir por qué Granados aparece en un lugar secundario en la historiografía española, y cómo y en base a qué premisas se conformó este canon musical. Palabras clave: Enrique Granados, canon, Nacionalismo, historiografia musical. Abstract Enrique Granados (1867-1916) is one of the three composers Who comprise the canon of Spanish nationalism, along With Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) and Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909). HoWeVer, in the realm of historical discourse, Granados has remained in the shadoW of his compatriots. MoreoVer, Granados lies outside the “foundational trio” of nationalism, formed by Felip Pedrell (1841-1922)— considered the teacher of the three nationalist composer and, as a consequence, the “father” of Spanish nationalism—Albéniz y Falla. Therefore, one of the objectiVes of this study is to discern why Granados occupies a secondary position in Spanish historiography, and most importantly, for What reasons the musical canon eVolVed as it did. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art This piano began life as a brown Recordo. The sound board was re-engineered, as the original ribs tapered so soon that the bass bridges pushed through. The strings were the wrong weight, and were re-scaled using computer technology. Six more wound-strings were added, and the weights of the steel strings were changed. A 14-inch Duo-Art pump, a fan-expression system, and an expression-valve-size Duo-Art stack with a soft-pedal compensation lift were all built for it. The Marquetry on the side of the piano was inspired by the pictures on the Arto-Roll boxes. The fallboard was inspired by a picture on the Rhythmodic roll box. A new bench was built, modeled after the bench originally available, but veneered to go with the rest of the piano. The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 42, NUMBER 5 Teresa Carreno (1853-1917) ISSN #1533-9726 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. AMICA was founded in San Francisco, California in 1963. PROFESSOR MICHAEL A. KUKRAL, PUBLISHER, 216 MADISON BLVD., TERRE HAUTE, IN 47803-1912 -- Phone 812-238-9656, E-mail: [email protected] Visit the AMICA Web page at: http://www.amica.org Associate Editor: Mr. Larry Givens VOLUME 42, Number -

El Flabiol De Cobla En El Segle Xx1

EL FLABIOL DE COBLA EN EL SEGLE XX1 Jordi León Royo (Barcelona), Pau Orriols Ramon (Vilanova i la Geltrú), amb la coŀlaboració de Josep Vilà Figueras (Cornellà de Llobregat) Jordi León Joaquim Serra, el 1948, va fer un curs d’instrumentació per a cobla, ja que coneixia molt bé les possibilitats tímbriques i sonores dels instruments que formen aquest conjunt. Més tard, l’Obra del Ballet Popular i altres institucions van tenir interès que això es publiqués, i en va sortir el Tractat d’instrumentació per a cobla, aparegut el 1957. Com qualsevol tractat d’instru- mentació, comença descrivint els instruments un per un i, quan parla del flabiol, després d’explicar quina és la seva extensió, la nota més greu, la nota més aguda, que està afinat en FA, que és un instrument transpositor, etc., diu textualment: «el flabiol és un instrument summament imperfecte, no és possible tro- bar-ne originàriament cap model ben afinat, i solament alguns flabiolaires amb bona voluntat, fent retocs als seus instruments, han aconseguit posar-lo en condicions acceptables d’afinació». És cert que, si mirem altres tractats d’orquestració, com pu- guin ser els que en el seu moment van escriure Hector Berlioz o Rimski-Kórsakov, hi trobarem moltes coses referides als instru- ments de la seva època, als instruments del segle xix, que ja no han estat vàlides per als instruments del segle xx i menys per als del xxi. El que vull dir amb això és que aquesta apreciació de Joaquim Serra de cap a 1950 avui dia ha passat de moda. -

Hifi/Stereo Review July 1959

• 99 BEST BUYS IN STEREO DISCS DAS RHEINGOLD - FINALLY I REVIEW July 1959 35¢ 1 2 . 3 ALL-IN-ONE STEREO RECEIVERS A N II' v:)ll.n EASY OUTDOOR HI-FI lAY 'ON W1HQI H 6 1 ~Z SltnOH l. ) b OC: 1 9~99 1 1 :1 HIS I THE AR THE HARMAN-KARDON STERE [ Available in three finishes: copper, brass and chrome satin the new STEREO FESTIVAL, model TA230 Once again Harman-Kardon has made the creative leap which distinguishes engineering leadership. The new Stereo Festival represents the successful crystallization of all stereo know-how in a single superb instrument. Picture a complete stereophonic electronic center: dual preamplifiers with input facility and control for every stereo function including the awaited FM multiplex service. Separate sensitive AM and FM tuners for simulcast reception. A great new thirty watt power amplifier (60 watts peak) . This is the new Stereo Festival. The many fine new Stereo Festival features include: new H-K Friction-Clutch tone controls to adjust bass and treble separately for each channel. Once used to correct system imbalance, they may be operated as conventionally ganged controls. Silicon power supply provides excellent regulation for improved transient response and stable tuner performance. D.C. heated preamplifier filaments insure freedom from hum. Speaker phasing switch corrects for improperly recorded program material. Four new 7408 output tubes deliver distortion-free power from two highly conservative power amplifier circuits. Additional Features: Separate electronic tuning bars for AM and FM; new swivel high Q ferrite loopstick for increased AM sensitivity; Automatic Frequency Control, Contour Selector, Rumble Filter, Scratch Filter, Mode Switch, Record-Tape Equalization Switch, two high gain magnetic inputs for each channel and dramatic new copper escutcheon. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008).