The Eighth Detective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Who's Feminine Mystique

Doctor Who’s Feminine Mystique: Examining the Politics of Gender in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke Professor Sarah Houser, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs Professor Kimberly Cowell-Meyers, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs University Honors in Political Science American University Spring 2014 Abstract In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan examined how fictional stories in women’s magazines helped craft a societal idea of femininity. Inspired by her work and the interplay between popular culture and gender norms, this paper examines the gender politics of Doctor Who and asks whether it subverts traditional gender stereotypes or whether it has a feminine mystique of its own. When Doctor Who returned to our TV screens in 2005, a new generation of women was given a new set of companions to look up to as role models and inspirations. Strong and clever, socially and sexually assertive, these women seemed to reject traditional stereotypical representations of femininity in favor of a new representation of femininity. But for all Doctor Who has done to subvert traditional gender stereotypes and provide a progressive representation of femininity, its story lines occasionally reproduce regressive discourses about the role of women that reinforce traditional gender stereotypes and ideologies about femininity. This paper explores how gender is represented and how norms are constructed through plot lines that punish and reward certain behaviors or choices by examining the narratives of the women Doctor Who’s titular protagonist interacts with. Ultimately, this paper finds that the show has in recent years promoted traits more in line with emphasized femininity, and that the narratives of the female companion’s have promoted and encouraged their return to domestic roles. -

The Torch, January/February 2020

KEEPING ON TRACK WITH NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTONS Written by Nicole Ellis, Year 13 Step Three: Ever find yourself, year after year, setting resolutions Create a list of all the different reasons why you set that you never actually end up achieving? Or maybe this goal in the first place, why it is important that you you’ve found yourself setting the exact same achieve it, and finally, what you will gain when you resolution as you did last year, because you never accomplish it. This way, every time you feel yourself actually achieved it? If this sounds like you, then keep being tempted to give up, you can go back to your list reading to find out how to well and truly follow and remind yourself why this goal is so personal and through on your goals for the new year... important to you. Step One: Step Four: Okay, so first things first, ask yourself is your goal Reward yourself for the mini successes along the way, attainable? Is it realistic? For instance, resolving to that you have set in the leading up to the full NEVER eat your favourite food again is more than likely accomplishment of your resolution. This will, again, to fail. Instead, set up a plan of action that will enable encourage you to not give up and also act as a you to reduce the amount of times you consume it and reminder for how much closer you’ve come to to help control any cravings. achieving your New Year’s intention, compared to at Step Two: the start of the year. -

THE NOTION of COMMITMENT in SELECTED WORKS of Mal SHE MAPONY A

THE NOTION OF COMMITMENT IN SELECTED WORKS OF MAl SHE MAPONY A THESIS Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Drama Department of Rhodes University BY MABITLE MOOROSI DECEMBER 1997 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR GARY GORDON l ABSTRACT This study is a critical analysis of selected works of the playwright Maishe Maponya namely, The Hungry Earth, Jika and Gangsters. The main thrust of the analysis of the thesis is centred on questions around what 'Commitment' might mean in literature and drama. This concept has appeared in many names and guises. In theatre, it has assumed names like Theatre of Commitment, Theatre of the Dispossessed, Theatre ofthe Oppressed, Theatre ofResistance, as well as Theatre ofRadicalization (Bentley 1968; Boal 1974; Mda 1985; Maponya 1992). These names came into existence as a result of a concerted effort to refrain from the use of the traditional conventional theatre, which does not appear to address itself to societal problems - the preoccupation of Theatre of Commitment. Chapter One is principally concerned with the concept of Commitment and its implications in art and literature, more specifically in theatre. Further, the following interacting elements in South African theatre are highlighted: censorship, banning, detention and other restrictions, as well as DET education and religious institutions. Finally, Maponya is introduced, with his political inclinations and his views on art, together with the issue of theatricality in his plays. Chapter two initiates the proposed critical analysis with a focus on The Hungry Earth. The focus is on Theatre of Commitment and the background events that inspired Maponya's response. -

The Carroll Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3 and No. 4

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll Quarterly Student Spring 1966 The aC rroll Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 3 and no. 4 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollquarterly Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 3 and no. 4" (1966). The Carroll Quarterly. 55. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollquarterly/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I' ... 1 .. •, '• , ., I > •' - I ~ ..·- \_,, L •t· ·• .. ~ I . t I " -. ,, / / t.-' \ 'I ..... r -, ' + ,, .\ r ~ ~• .!"' • -: .,. ,.. I' . "~ ,. I ~ .,, I .... Carroll Quarterly, a literary magazine produced by an undergraduate staff and written by the students, alumni, and fac ulty of John Carroll University, Cleveland, Ohio. Volume 19 Spring, 1966 Numbers 3 and 4 Editor-in-Chief TONY KUHN Assistant Editors RICHARD TOMC TIM BURNS LARRY RYAN RODERICK PORTER WILLIAM DeLONG TOM O'CONNOR Managing Editor RODERICK PORTER Editorial Assistant WILLIAM DeLONG Copy Editors LARRY RYAN JOHN SANTORO Faculty Advisor LOUIS G. PECEK Contents A Moment in the Awakening of China Edmund S. Wehrle . 6 Alone, the House on No Hill Gerald FitzGerald . 12 Once a Lover (for G.T.) Gerald FitzGerald . 13 Come Die with Me This Monday Morning Gerald FitzGerald . 14 Rebecca's Drowning in a Country Stream Gerald FitzGerald . 15 See You in the Morning Gerald FitzGerald . 16 A Miniature Portrait Philip Parkhurst . -

Tekan Bagi Yang Ingin Order Via DVD Bisa Setelah Mengisi Form Lalu

DVDReleaseBest 1Seller 1 1Date 1 Best4 15-Nov-2013 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 1 1-Dec-2014 1 Seller 1 2 1 Best1 1 30-Nov-20141 Seller 1 6 2 Best 4 1 9 Seller29-Nov-2014 2 1 1 1Best 1 1 Seller1 28-Nov-2014 1 1 1 Best 1 1 9Seller 127-Nov-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 326-Nov-2014 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 1 25-Nov-20141 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 24-Nov-2014Best1 1 1 Seller 1 2 1 1 Best23-Nov- 1 1 1Seller 8 1 2 142014Best 3 1 Seller22-Nov-2014 1 2 6Best 1 1 Seller2 121-Nov-2014 1 2Best 2 1 Seller8 2 120-Nov-2014 1Best 9 11 Seller 1 1 419-Nov-2014Best 1 3 2Seller 1 1 3Best 318-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 17-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 1 1 Best 1 1 16-Nov-20141Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 15-Nov-2014 1 1 1Best 2 1 Seller1 1 14-Nov-2014 1 1Best 1 1 Seller2 2 113-Nov-2014 5 Best1 1 2 Seller 1 1 112- 1 1 2Nov-2014Best 1 2 Seller1 1 211-Nov-2014 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best110-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 2 Best1 9-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 18-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 3 2Best 17-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 6-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 2 1 Best1 4-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 14-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 13-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 1 13-Nov-2014Best 1 1 Seller1 1 1 Best12-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 2-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 3 1 1 Best1 1-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best5 1-Nov-20141 2 Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 31-Oct-20141 1Seller 1 2 1 Best 1 1 31-Oct-2014 1Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 31-Oct-2014Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 Seller 131-Oct-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 30-Oct-20141 1 Best 1 3 1Seller 1 1 30-Oct-2014 1 Best1 -

Post-Feminist Retreatism in Doctor Who Franke, A

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Don't make me go back': post-feminist retreatism in Doctor Who Franke, A. and Nicol, D. This is an author accepted manuscript of an article published by Intellect in the Journal of Popular Television, 6 (2), pp. 197-211. The final definitive version is available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jptv.6.2.197_1 © 2018 Intellect The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] ‘Don’t Make Me Go Back’: Post-Feminist Retreatism in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke and Danny Nicol ABSTRACT In post-2005 Doctor Who the female companion has become a seminal figure. This article shows how closely the narratives of the companions track contemporary notions of post- feminism. In particular, companions’ departures from the programme have much in common with post-feminism’s master-theme of retreatism, whereby women retreat from their public lives to find fulfilment in marriage, home and family. The article argues that when companions leave the TARDIS, what happens next ought to embody the sense of empowerment, purpose and agency which they have gained through their adventures, whereas too often the programme’s authors have given companions ‘happy endings’ based on finding husbands and settling down. -

Termcard: Trinity Term 2018

OXFORD UNIVERSITY DOCTOR WHO SOCIETY Termcard: Trinity Term 2018 1 th st Thursday 26 April Remembrance of the We begin Trinity term with a gold-tier Dalek Week 8pm Daleks spectacular featuring the Seventh Doctor and Ace. Seminar Room Fewer wizards and Nazis than last meeting’s Silver West, Mansfield Nemesis, but there are plenty more Daleks, more College surprise twists and more iconic moments. Steven Moffat mentioned it at his Oxford Union talk: “This is the only show in the world where the evil monster demonstrates its Satanic power by… ascending a staircase!” 2 rd nd Thursday 3 May The Enemy of the World Five years ago, nine previously missing Second Doctor Week 8pm episodes were recovered in Nigeria and released to Seminar Room the public. Of those, five came from The Enemy of the West, Mansfield World, a now-complete political thriller which has just College been re-released as a Special Edition. It’s time to venture forward in time to the year two thousand and eighteen where world-famous scientist and politician Salamander (played by a particularly busy Patrick Troughton) tries to conceal his plans for world domination… Saturday 5th May Chris Chibnall Marathon! Our soon-to-be lord and master (head writer and 12:30-5:30pm showrunner Chris Chibnall) has a proven track record 24 Beaumont writing for the Doctor Who universe. His episodes for Street (Worcester the main show in particular have notoriously been College) plagued by budget cuts and impossible deadlines, but they’re all worth a watch! First, the Tenth Doctor and Martha swelter as they try to save the TARDIS and stop a spaceship from hurtling towards a sun while crew members become murderous heat creatures in 42. -

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date

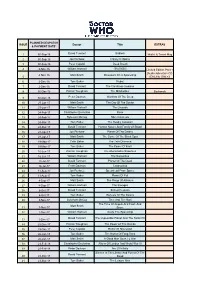

PLANNED DESPATCH ISSUE Doctor Title EXTRAS & PAYMENT DATE* 1 30-Sep-16 David Tennant Gridlock Wallet & Travel Mug 2 30-Sep-16 Jon Pertwee Colony In Space 3 30-Sep-16 Peter Capaldi Deep Breath 4 4-Nov-16 William Hartnell 100,000BC Limited Edition Print + [Audio Adventure CD 4-Nov-16 Matt Smith Dinosaurs On A Spaceship 5 (ONLINE ONLY)] 6 2-Dec-16 Tom Baker Robot 7 2-Dec-16 David Tennant The Christmas Invasion 8 30-Dec-16 Patrick Troughton The Mindrobber Bookends 9 30-Dec-16 Peter Davison Warriors Of The Deep 10 27-Jan-17 Matt Smith The Day Of The Doctor 11 27-Jan-17 William Hartnell The Crusade 12 24-Feb-17 Christopher Eccleston Rose 13 24-Feb-17 Sylvester McCoy Silver Nemesis 14 24-Mar-17 Tom Baker The Deadly Assassin 15 24-Mar-17 David Tennant Human Nature And Family Of Blood 16 21-Apr-17 Jon Pertwee Planet Of The Daleks 17 21-Apr-17 Matt Smith The Curse Of The Black Spot 18 19-May-17 Colin Baker The Twin Dilemma 19 19-May-17 Tom Baker The Power Of Kroll 20 16-Jun-17 Patrick Troughton The Abominable Snowmen 21 16-Jun-17 William Hartnell The Sensorites 22 14-Jul-17 David Tennant Planet Of The Dead 23 14-Jul-17 Peter Davison Castrovalva 24 11-Aug-17 Jon Pertwee Spearhead From Space 25 11-Aug-17 Tom Baker Planet Of Evil 26 8-Sep-17 Matt Smith The Rings Of Akhaten 27 8-Sep-17 William Hartnell The Savages 28 6-Oct-17 David Tennant School Reunion 29 6-Oct-17 Tom Baker Genesis Of The Daleks 30 3-Nov-17 Sylvester McCoy Time And The Rani The Time Of Angels And Flesh And Matt Smith 31 3-Nov-17 Stone 32 1-Dec-17 William Hartnell Inside The Spaceship -

Orthodoxy: Its Truths and Errors by James Freeman Clarke

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Orthodoxy: Its Truths And Errors by James Freeman Clarke This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Orthodoxy: Its Truths And Errors Author: James Freeman Clarke Release Date: June 6, 2009 [Ebook 29054] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ORTHODOXY: ITS TRUTHS AND ERRORS*** Orthodoxy: Its Truths And Errors By James Freeman Clarke “Soleo enim in allena castra transire, non tanquam transfuga, sed tanquam explorator.”—SENECA, Epistolæ, 2. “Fiat lux. Cupio refelli, ubi aberrarim; nihil majus, nihil aliud quam veritatem efflagito.”—THOMAS BURNET, Arch. Phil. Fourteenth Edition. Boston: American Unitarian Association. 1880. Contents Preface. .2 Chapter I. Introduction. .3 § 1. Object and Character of this Book. .3 § 2. Progress requires that we should look back as well as forward. .5 § 3. Orthodoxy as Right Belief. .6 § 4. Orthodoxy as the Doctrine of the Majority. Objections. .9 § 5. Orthodoxy as the Oldest Doctrine. Objections. 11 § 6. Orthodoxy as the Doctrine held by all. 12 § 7. Orthodoxy, as a Formula, not to be found. 13 § 8. Orthodoxy as Convictions underlying Opinions. 13 § 9. Substantial Truth and Formal Error in all great Doctrinal Systems. 15 § 10. Importance of this Distinction. 17 § 11. The Orthodox and Liberal Parties in New England. 19 Chapter II. The Principle And Idea Of Orthodoxy Stated And Examined. 22 § 1. -

True Crime Laura Browder University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository English Faculty Publications English 2010 True Crime Laura Browder University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Browder, Laura. "True Crime." In The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction, edited by Catherine Nickerson, 205-28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 11 LAURA BROWDER True crime Over forty-two years ago, Truman Capote wrote a bestselling book, In Cold Blood, and loudly proclaimed that he had invented a new art form. As Capote told George Plimpton in a long interview: “journalism, reportage, could be forced to yield a serious new art form: the ‘nonfiction novel,’” and that “a crime, the study of one such, might provide the broad scope I needed to write the kind of book I wanted to write. Moreover, the human heart being what it is, murder was a theme not likely to darken and yellow with time.”1 Whether or not Capote invented something called the “nonfiction novel,” he ushered in the serious, extensive, non-fiction treatment of murder. In the years since In Cold Blood appeared, the genre of true crime regularly appears on the bestseller list. It is related to crime fiction, certainly – but it might equally well be grouped with documentary or read alongside romance fiction. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

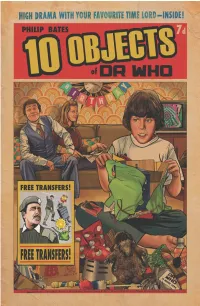

10 Objects of Dr

The right of Philip Bates to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. An unofficial Doctor Who Publication Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2021 Editor: Shaun Russell Editorial: Will Rees Cover and illustrations by Martin Baines Published by Candy Jar Books Mackintosh House 136 Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 1DJ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Come one, come all, to the Museum of ! Located on the SS. Shawcraft and touring the Seven Systems, right now! Are you a fully-grown human adult? I would like to speak to someone in charge, so please direct me to any children in the vicinity. No, no, that's not fair – I was programmed not to judge, for I am a simple advertisement bot, bringing you the best in junk mail. Are you always that short? No, don’t look at me like that: my creators were from Ravan-Skala, where the people are six hundred ft tall; you have to talk to them in hot air balloons, and the tourist information centre is made of one of their hats.