THE NOTION of COMMITMENT in SELECTED WORKS of Mal SHE MAPONY A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Who's Feminine Mystique

Doctor Who’s Feminine Mystique: Examining the Politics of Gender in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke Professor Sarah Houser, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs Professor Kimberly Cowell-Meyers, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs University Honors in Political Science American University Spring 2014 Abstract In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan examined how fictional stories in women’s magazines helped craft a societal idea of femininity. Inspired by her work and the interplay between popular culture and gender norms, this paper examines the gender politics of Doctor Who and asks whether it subverts traditional gender stereotypes or whether it has a feminine mystique of its own. When Doctor Who returned to our TV screens in 2005, a new generation of women was given a new set of companions to look up to as role models and inspirations. Strong and clever, socially and sexually assertive, these women seemed to reject traditional stereotypical representations of femininity in favor of a new representation of femininity. But for all Doctor Who has done to subvert traditional gender stereotypes and provide a progressive representation of femininity, its story lines occasionally reproduce regressive discourses about the role of women that reinforce traditional gender stereotypes and ideologies about femininity. This paper explores how gender is represented and how norms are constructed through plot lines that punish and reward certain behaviors or choices by examining the narratives of the women Doctor Who’s titular protagonist interacts with. Ultimately, this paper finds that the show has in recent years promoted traits more in line with emphasized femininity, and that the narratives of the female companion’s have promoted and encouraged their return to domestic roles. -

The Eighth Detective

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Henry Holt and Company ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. 1 SPAIN, 1930 The two suspects sat on mismatched furniture in the white and almost featureless lounge, waiting for something to happen. Between them an archway led to a slim, windowless staircase: a dim recess that seemed to dominate the room, like a fireplace grown to unreasonable proportions. The staircase changed direction at its midpoint, hiding the upper floor from view and giving the impression that it led up to darkness and nothing else. “It’s hell, just waiting here.” Megan was sitting to the right of the archway. “How long does a siesta normally take, anyway?” She walked over to the window. Outside, the Spanish countryside was an indistinct orange color. It looked uninhabitable in the heat. “An hour or two, but he’s been drinking.” Henry was sitting sideways in his chair, with his legs hooked over the arm and a guitar resting on his lap. -

The Torch, January/February 2020

KEEPING ON TRACK WITH NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTONS Written by Nicole Ellis, Year 13 Step Three: Ever find yourself, year after year, setting resolutions Create a list of all the different reasons why you set that you never actually end up achieving? Or maybe this goal in the first place, why it is important that you you’ve found yourself setting the exact same achieve it, and finally, what you will gain when you resolution as you did last year, because you never accomplish it. This way, every time you feel yourself actually achieved it? If this sounds like you, then keep being tempted to give up, you can go back to your list reading to find out how to well and truly follow and remind yourself why this goal is so personal and through on your goals for the new year... important to you. Step One: Step Four: Okay, so first things first, ask yourself is your goal Reward yourself for the mini successes along the way, attainable? Is it realistic? For instance, resolving to that you have set in the leading up to the full NEVER eat your favourite food again is more than likely accomplishment of your resolution. This will, again, to fail. Instead, set up a plan of action that will enable encourage you to not give up and also act as a you to reduce the amount of times you consume it and reminder for how much closer you’ve come to to help control any cravings. achieving your New Year’s intention, compared to at Step Two: the start of the year. -

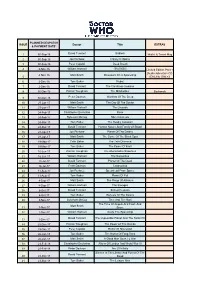

Doctor Who Episode Data, 2005-20

Episode Information BBC IMDB Series # Title Date Year XMAS AI Chart Rating # User-Raters 1 1 Rose 3/26/2005 2005 0 76 7 7.5 7,027 1 2 The End of the World 4/2/2005 2005 0 76 19 7.6 6,136 1 3 The Unquiet Dead 4/9/2005 2005 0 80 15 7.6 7,578 1 4 Aliens of London 4/16/2005 2005 0 82 18 7.0 5,516 1 5 World War III 4/23/2005 2005 0 81 20 7.0 5,327 1 6 Dalek 4/30/2005 2005 0 84 14 8.7 6,065 1 7 The Long Game 5/7/2005 2005 0 81 17 7.1 5,253 1 8 Father's Day 5/14/2005 2005 0 83 17 8.4 5,839 1 9 The Empty Child 5/21/2005 2005 0 84 21 9.2 7,138 1 10 The Doctor Dances 5/28/2005 2005 0 85 18 9.1 6,547 1 11 Boom Town 6/4/2005 2005 0 82 18 7.1 5,013 1 12 Bad Wolf 6/11/2005 2005 0 86 19 8.7 5,727 1 13 The Parting of the Ways 6/18/2005 2005 0 89 17 9.1 6,196 2 0 The Christmas Invasion 12/25/2005 2005 1 84 9 8.1 5,692 2 1 New Earth 4/15/2006 2006 0 85 9 7.4 5,281 2 2 Tooth and Claw 4/22/2006 2006 0 83 10 7.8 5,418 2 3 School Reunion 4/29/2006 2006 0 85 12 8.3 5,795 2 4 The Girl in the Fireplace 5/6/2006 2006 0 84 13 9.3 9,064 2 5 Rise of the Cybermen 5/13/2006 2006 0 86 6 7.8 5,050 2 6 The Age of Steel 5/20/2006 2006 0 86 15 7.9 4,994 2 7 The Idiot's Lantern 5/27/2006 2006 0 84 18 6.7 5,175 2 8 The Impossible Planet 6/3/2006 2006 0 85 18 8.7 5,817 2 9 The Satan Pit 6/10/2006 2006 0 86 19 8.8 6,027 2 10 Love & Monsters 6/17/2006 2006 0 76 15 6.1 6,150 2 11 Fear Her 6/24/2006 2006 0 83 20 6.0 5,405 2 12 Army of Ghosts 7/1/2006 2006 0 86 7 8.5 5,252 2 13 Doomsday 7/8/2006 2006 0 89 8 9.3 7,291 3 0 The Runaway Bride 12/25/2006 2006 1 84 10 7.6 5,388 3 1 Smith -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

The Carroll Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3 and No. 4

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll Quarterly Student Spring 1966 The aC rroll Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 3 and no. 4 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollquarterly Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 3 and no. 4" (1966). The Carroll Quarterly. 55. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollquarterly/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I' ... 1 .. •, '• , ., I > •' - I ~ ..·- \_,, L •t· ·• .. ~ I . t I " -. ,, / / t.-' \ 'I ..... r -, ' + ,, .\ r ~ ~• .!"' • -: .,. ,.. I' . "~ ,. I ~ .,, I .... Carroll Quarterly, a literary magazine produced by an undergraduate staff and written by the students, alumni, and fac ulty of John Carroll University, Cleveland, Ohio. Volume 19 Spring, 1966 Numbers 3 and 4 Editor-in-Chief TONY KUHN Assistant Editors RICHARD TOMC TIM BURNS LARRY RYAN RODERICK PORTER WILLIAM DeLONG TOM O'CONNOR Managing Editor RODERICK PORTER Editorial Assistant WILLIAM DeLONG Copy Editors LARRY RYAN JOHN SANTORO Faculty Advisor LOUIS G. PECEK Contents A Moment in the Awakening of China Edmund S. Wehrle . 6 Alone, the House on No Hill Gerald FitzGerald . 12 Once a Lover (for G.T.) Gerald FitzGerald . 13 Come Die with Me This Monday Morning Gerald FitzGerald . 14 Rebecca's Drowning in a Country Stream Gerald FitzGerald . 15 See You in the Morning Gerald FitzGerald . 16 A Miniature Portrait Philip Parkhurst . -

Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas Mcmurtry, LG

Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas McMurtry, LG Title Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas Authors McMurtry, LG Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/44368/ Published Date 2013 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Leslie McMurtry Swansea University Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas “It’s everywhere these days, isn’t it? Anime, Doctor Who, novel after novel involving clockwork and airships.” --Catherynne M. Valente1 Introduction It seems nearly every article or essay on Neo-Victorianism must, by tradition, begin with a defence of the discipline and an explanation of what is currently encompassed by the term— or, more likely, what is not. Since at least 2008 and the launch of the interdisciplinary journal Neo-Victorian Studies, scholars have been grappling with a catch-all definition for the term. Though it is appropriate that Mark Llewellyn should note in his 2008 “What Is Neo-Victorian Studies?” that “in bookstores and TV guides all around us what we see is the ‘nostalgic tug’ that the (quasi-) Victorian exerts on the mainstream,” Imelda Whelehan is right to suggest that the novel is the supreme and legitimizing source2. -

Tekan Bagi Yang Ingin Order Via DVD Bisa Setelah Mengisi Form Lalu

DVDReleaseBest 1Seller 1 1Date 1 Best4 15-Nov-2013 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 1 1-Dec-2014 1 Seller 1 2 1 Best1 1 30-Nov-20141 Seller 1 6 2 Best 4 1 9 Seller29-Nov-2014 2 1 1 1Best 1 1 Seller1 28-Nov-2014 1 1 1 Best 1 1 9Seller 127-Nov-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 326-Nov-2014 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 1 25-Nov-20141 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 24-Nov-2014Best1 1 1 Seller 1 2 1 1 Best23-Nov- 1 1 1Seller 8 1 2 142014Best 3 1 Seller22-Nov-2014 1 2 6Best 1 1 Seller2 121-Nov-2014 1 2Best 2 1 Seller8 2 120-Nov-2014 1Best 9 11 Seller 1 1 419-Nov-2014Best 1 3 2Seller 1 1 3Best 318-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 17-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 1 1 Best 1 1 16-Nov-20141Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 15-Nov-2014 1 1 1Best 2 1 Seller1 1 14-Nov-2014 1 1Best 1 1 Seller2 2 113-Nov-2014 5 Best1 1 2 Seller 1 1 112- 1 1 2Nov-2014Best 1 2 Seller1 1 211-Nov-2014 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best110-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 2 Best1 9-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 18-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 3 2Best 17-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 6-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 2 1 Best1 4-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 14-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 13-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 1 13-Nov-2014Best 1 1 Seller1 1 1 Best12-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 2-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 3 1 1 Best1 1-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best5 1-Nov-20141 2 Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 31-Oct-20141 1Seller 1 2 1 Best 1 1 31-Oct-2014 1Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 31-Oct-2014Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 Seller 131-Oct-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 30-Oct-20141 1 Best 1 3 1Seller 1 1 30-Oct-2014 1 Best1 -

Post-Feminist Retreatism in Doctor Who Franke, A

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Don't make me go back': post-feminist retreatism in Doctor Who Franke, A. and Nicol, D. This is an author accepted manuscript of an article published by Intellect in the Journal of Popular Television, 6 (2), pp. 197-211. The final definitive version is available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jptv.6.2.197_1 © 2018 Intellect The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] ‘Don’t Make Me Go Back’: Post-Feminist Retreatism in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke and Danny Nicol ABSTRACT In post-2005 Doctor Who the female companion has become a seminal figure. This article shows how closely the narratives of the companions track contemporary notions of post- feminism. In particular, companions’ departures from the programme have much in common with post-feminism’s master-theme of retreatism, whereby women retreat from their public lives to find fulfilment in marriage, home and family. The article argues that when companions leave the TARDIS, what happens next ought to embody the sense of empowerment, purpose and agency which they have gained through their adventures, whereas too often the programme’s authors have given companions ‘happy endings’ based on finding husbands and settling down. -

Termcard: Trinity Term 2018

OXFORD UNIVERSITY DOCTOR WHO SOCIETY Termcard: Trinity Term 2018 1 th st Thursday 26 April Remembrance of the We begin Trinity term with a gold-tier Dalek Week 8pm Daleks spectacular featuring the Seventh Doctor and Ace. Seminar Room Fewer wizards and Nazis than last meeting’s Silver West, Mansfield Nemesis, but there are plenty more Daleks, more College surprise twists and more iconic moments. Steven Moffat mentioned it at his Oxford Union talk: “This is the only show in the world where the evil monster demonstrates its Satanic power by… ascending a staircase!” 2 rd nd Thursday 3 May The Enemy of the World Five years ago, nine previously missing Second Doctor Week 8pm episodes were recovered in Nigeria and released to Seminar Room the public. Of those, five came from The Enemy of the West, Mansfield World, a now-complete political thriller which has just College been re-released as a Special Edition. It’s time to venture forward in time to the year two thousand and eighteen where world-famous scientist and politician Salamander (played by a particularly busy Patrick Troughton) tries to conceal his plans for world domination… Saturday 5th May Chris Chibnall Marathon! Our soon-to-be lord and master (head writer and 12:30-5:30pm showrunner Chris Chibnall) has a proven track record 24 Beaumont writing for the Doctor Who universe. His episodes for Street (Worcester the main show in particular have notoriously been College) plagued by budget cuts and impossible deadlines, but they’re all worth a watch! First, the Tenth Doctor and Martha swelter as they try to save the TARDIS and stop a spaceship from hurtling towards a sun while crew members become murderous heat creatures in 42. -

The Unkindness of Ravens

It is the 41st millennium. For more than a hundred centuries the Emperor has sat immobile on the Golden Throne of Earth. He is the master of mankind by the will of the gods, and master of a million worlds by the might of his inexhaustible armies. He is a rotting carcass writhing invisibly with power from the Dark Age of Technology. He is the Carrion Lord of the Imperium for whom a thousand souls are sacrificed every day, so that he may never truly die. Yet even in his deathless state, the Emperor continues his eternal vigilance. Mighty battlefleets cross the daemon-infested miasma of the warp, the only route between distant stars, their way lit by the Astronomican, the psychic manifestation of the Emperor’s will. Vast armies give battle in His name on uncounted worlds. Greatest amongst his soldiers are the Adeptus Astartes, the Space Marines, bioengineered super-warriors. Their comrades in arms are legion: the Imperial Guard and countless planetary defence forces, the ever-vigilant Inquisition and the tech-priests of the Adeptus Mechanicus to name only a few. But for all their multitudes, they are barely enough to hold off the ever-present threat from aliens, heretics, mutants—and worse. To be a man in such times is to be one amongst untold billions. It is to live in the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable. These are the tales of those times. Forget the power of technology and science, for so much has been forgotten, never to be relearned. Forget the promise of progress and understanding, for in the grim dark future there is only war. -

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date

PLANNED DESPATCH ISSUE Doctor Title EXTRAS & PAYMENT DATE* 1 30-Sep-16 David Tennant Gridlock Wallet & Travel Mug 2 30-Sep-16 Jon Pertwee Colony In Space 3 30-Sep-16 Peter Capaldi Deep Breath 4 4-Nov-16 William Hartnell 100,000BC Limited Edition Print + [Audio Adventure CD 4-Nov-16 Matt Smith Dinosaurs On A Spaceship 5 (ONLINE ONLY)] 6 2-Dec-16 Tom Baker Robot 7 2-Dec-16 David Tennant The Christmas Invasion 8 30-Dec-16 Patrick Troughton The Mindrobber Bookends 9 30-Dec-16 Peter Davison Warriors Of The Deep 10 27-Jan-17 Matt Smith The Day Of The Doctor 11 27-Jan-17 William Hartnell The Crusade 12 24-Feb-17 Christopher Eccleston Rose 13 24-Feb-17 Sylvester McCoy Silver Nemesis 14 24-Mar-17 Tom Baker The Deadly Assassin 15 24-Mar-17 David Tennant Human Nature And Family Of Blood 16 21-Apr-17 Jon Pertwee Planet Of The Daleks 17 21-Apr-17 Matt Smith The Curse Of The Black Spot 18 19-May-17 Colin Baker The Twin Dilemma 19 19-May-17 Tom Baker The Power Of Kroll 20 16-Jun-17 Patrick Troughton The Abominable Snowmen 21 16-Jun-17 William Hartnell The Sensorites 22 14-Jul-17 David Tennant Planet Of The Dead 23 14-Jul-17 Peter Davison Castrovalva 24 11-Aug-17 Jon Pertwee Spearhead From Space 25 11-Aug-17 Tom Baker Planet Of Evil 26 8-Sep-17 Matt Smith The Rings Of Akhaten 27 8-Sep-17 William Hartnell The Savages 28 6-Oct-17 David Tennant School Reunion 29 6-Oct-17 Tom Baker Genesis Of The Daleks 30 3-Nov-17 Sylvester McCoy Time And The Rani The Time Of Angels And Flesh And Matt Smith 31 3-Nov-17 Stone 32 1-Dec-17 William Hartnell Inside The Spaceship