Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas Mcmurtry, LG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

DOCTOR WHO LOGOPOLIS Christopher H. Bidmead Based On

DOCTOR WHO LOGOPOLIS Christopher H. Bidmead Based on the BBC television serial by Christopher H. Bidmead by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation 1. Events cast shadows before them, but the huger shadows creep over us unseen. When some great circumstance, hovering somewhere in the future, is a catastrophe of incalculable consequence, you may not see the signs in the small happenings that go before. The Doctor did, however - vaguely. While the Doctor paced back and forth in the TARDIS cloister room trying to make some sense of the tangle of troublesome thoughts that had followed him from Traken, in a completely different sector of the Universe, in a place called Earth, one such small foreshadowing was already beginning to unfold. It was a simple thing. A policeman leaned his bicycle against a police box, took a key from the breast pocket of his uniform jacket and unlocked the little telephone door to make a phone call. Police Constable Donald Seagrave was in a jovial mood. The sun was shining, the bicycle was performing perfectly since its overhaul last Saturday afternoon, and now that the water-main flooding in Burney Street was repaired he was on his way home for tea, if that was all right with the Super. It seemed to be a bad line. Seagrave could hear his Superintendent at the far end saying, 'Speak up . Who's that . .?', but there was this whirring noise, and then a sort of chuffing and groaning . The baffled constable looked into the telephone, and then banged it on his helmet to try to improve the connection. -

The Representation, Interpretation and Staging of Magic in Renaissance Plays from the Sixteenth Century Onwards

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The representation, interpretation and staging of magic in Renaissance plays from the sixteenth century onwards. A case study of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Macbeth and Cristopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Professor Doctor fulfilment of the requirements for Sandro Jung the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: English-Spanish” by Tine Dekeyser August 2014 Word count: 27334 Dekeyser i Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Doctor Sandro Jung, for granting me the opportunity to continue working on the same topic of my BA-dissertation and for guiding me towards a more profound investigation of magic and the Renaissance society. Also, I want to thank Professor Jung for reading the many versions of this dissertation and for providing a lot of helpful suggestions throughout the year. Secondly, I would like to thank The British Museum for giving me permission to use their highly detailed engravings, without which this dissertation would not exist. Thirdly, I would like to thank my boyfriend and my mother for supporting me, listening to my dilemmas and calming me down when stress got the better of me. Also, I want to thank my boyfriend for helping me track down the movies I needed for my analyses. Dekeyser ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................... -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

1 2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15

2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15, 2019 3:00-3:15 KEYNOTE “The Fandom Hierarchy: Women of Color’s Fight For Visibility In Fandom Spaces” Tai Gooden Women of Color (WoC) have been fervent Doctor Who fans for several decades. However, the fandom often reflects societal hierarchies upheld by White privilege that result in ignoring and diminishing WoC’s opinions, contributions, and legitimate concerns about issues in terms of representation. Additionally, WoC and non-binary (NB) people of color’s voices are not centered as often in journalism, podcasting, and media formats nor convention panels as much as their White counterparts. This noticeable disparity has led to many WoC, even those who are deemed “important” in fandom spaces, to encounter racism, sexism, and, depending on the individual, homophobia and transphobia in a place that is supposed to have open availability to everyone. I can attest to this experience as someone who has a somewhat heightened level of visibility in fandom as a pop culture/entertainment writer who extensively covers Doctor Who. This presentation will examine women of color in the Doctor Who fandom in terms of their interactions with non-POC fans and difficulties obtaining opportunities in media, online, and at conventions. The show’s representation of fandom and the necessity for equity versus equality will also be discussed to craft a better understanding of how to tackle this pervasive issue. Other actionable solutions to encourage intersectionality in the fandom will be discussed including privileged people listening to WoC and non- binary people’s concerns/suggestions, respectfully interacting with them online and in person, recognizing and utilizing their privilege to encourage more inclusivity, standing in solidarity with them on critical issues, and lending their support to WoC creatives. -

The Early Adventures 6.1 the Home Guard Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE EARLY ADVENTURES 6.1 THE HOME GUARD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Guerrier | none | 31 Dec 2019 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781787038639 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom The Early Adventures 6.1 The Home Guard PDF Book Fourth Doctor 2. People are so quick to say big finish copy the new series but most of the time such as a story with 2 masters it was done by big finish and then copied by the TV. Funko scale figurine collection Eaglemoss scale figurines Robert Harrop 38mm miniatures collection Warlord Games scale collector figures Big Chief Studios 3. Skip to main content. Buy It Now. Blood of the Daleks Doctor Who. Binding: CD. PG min Action, Crime, Drama. Various interconnected people struggle to survive when an earthquake of unimaginable magnitude hits Los Angeles, California. About this product. R min Action, Horror, Sci-Fi. When LexCorps accidentally unleash a murderous creature, Doomsday, Superman meets his greatest challenge as a champion. Southern Comfort R min Action, Thriller 7. Also a massive Zoe fan! View all Our Sites. But Di Bruno Bros. See details for additional description. Darren Jones. Author: Guerrier, Simon. R 92 min Comedy, Drama. The Companion Chronicles 12 3. June 17th, 7 comments. Doctor Who: Molten Heart. Steve Tribe. The Early Adventures 6.1 The Home Guard Writer R min Action, Horror, Sci-Fi. Fact-based drama set during the Detroit riots in which a group of rogue police officers respond to a complaint with retribution rather than justice on their minds. Do you think more stories should be explored with this incarnation of the Master? PG min Drama, Romance. -

Doctorwhotimeofthedaleks.Pdf

1 COMPONENTS TIME OF THE DALEKS EARTH AND THE WEB OF TIME BOARD TARDIS DIE The TARDIS die is used Somewhere, sometime, the Cloister Bell echoed throughout The Earth and Web of Time board combines the Earth GAME OVERVIEW when traveling through the heart of the TARDIS. location and the Web of Time track. In Doctor Who: Time of the Daleks, Davros has time and space. The Doctor started to feel a twinge, slowly turning into infiltrated the Matrix on Gallifrey, mapping out the • Earth is a location that has three Time Zones. a searing pain. Daleks. The Doctor could see them in his • The Web of Time is used to monitor progress in the Doctor’s timeline and devising the best way to wipe TIME ANOMALY CARDS memories but they were never there, that never happened. him from history. game, as the Doctors and Dalek progress towards Why is Davros in the matrix? Why is he on Gallifrey? Gallifrey. Any time a game effect tells you to move Time Anomalies are massive events that happen as the Players take on the role of the Doctor, travelling a TARDIS or the Dalek Ship, it well tell you to game progresses. Each Time Anomaly card presents a “Doctor!” Clara screamed as she saw the Doctor vanish into throughout time and space, finding new Companions move it forward towards Gallifrey or backwards unique problem to solve. thin air and reappear seconds later. and having adventures to repair the web of time. toward Skaro. “I don’t want to alarm you Clara, but I may be ending.” The Players do this by overcoming challenges. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Doctor Who: Cyberman Bust and Illustrated Book Free

FREE DOCTOR WHO: CYBERMAN BUST AND ILLUSTRATED BOOK PDF Running Press | 32 pages | 24 Sep 2013 | Running Press | 9780762450862 | English | Philadelphia, United States Cyberman Bust and Illustrated Book Pictures – Merchandise Guide - The Doctor Who Site September 25th, 62 comments. Available to order from www. USA customers can order this item from www. By www. Despite their appearance, the Cybermen are not robots. They were once humans, but have used cybernetic parts to replace limbs and organs, augmenting their organic brains with implants and computer programming. Categorised under: General toysToys. Is the box a promo image from before the release, cos the bust is different to the picture Neck design, top of head etc. The Dalek is disproportioned but not badly. It is quite good quality for the money. The Tardis is very Doctor Who: Cyberman Bust and Illustrated Book especially with the light. Again good quality at the price. I wonder when someone will have the idea of producing a box set with a figure of every variant of Doctor Who: Cyberman Bust and Illustrated Book specifically for display…. Ive given up on Characters options and underground toys and whoever backs them completing the set now…. Saying that, it is fairly cheap. Ive got to say they can keep augmenting the cybermen as much as they like but they still dont look as good as the classic variations…. The old ones were best but the last design was ok. Cannot understand why change. The cybermen were just blend in my opinion. These new designs actually remind me of the classic series cybermen. -

This Little Life

This Little Life This Little Life Introduction . 15 Production notes . 17 Cast and production credits . 18 Interviews with the cast: . Kate Ashfield plays Sadie . 19 David Morrissey plays Richie . 21 This Little Life 14 Introduction This Little Life Kate Ashfield, David Morrissey and Peter Mullan charged with balancing his emotions for Luke with star in This Little Life, winner of the prestigious his momentous medical responsibilities. Dennis Potter Screenwriting Award. This Little Life is a film jointly commissioned by BBC Films and the Rosemary Kay’s screenplay was awarded the BBC’s Film Council’s New Cinema Fund for BBC Two. Dennis Potter Screenwriting Award, a scheme set up in 1995 to nurture and encourage the work of Directed by Sarah Gavron, winner of the RTS Best new writers with talent and personal vision. This New Director Award for her film Losing Touch,This Little Life is an adaptation of Kay’s novel Between Little Life is the moving story of a premature baby’s Two Eternities, a fictional memoir based on the fragile existence and a mother’s supreme trust and author’s own experiences during her son’s tragic betrayal. premature birth. Luke is born prematurely, weighing only one pound Jane Tranter, BBC Controller of Drama and four ounces. He is too small to be cradled in Commissioning, says:“This Little Life is a powerful his mother’s arms but can be held in the palm of piece of work that is part of the BBC’s ongoing, her hand. Everything possible is done to keep him practical commitment not just to finding and alive, but what does her son want and what will nurturing new talent, but also to getting their work medical science allow? Luke’s mother, Sadie, made and seen.” desperately wants him to have a voice and, through her friendship with a young boy, mother and son David Thompson, Head of BBC Films, says:“The find a way to talk. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

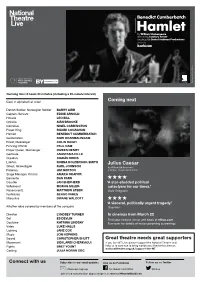

NTL-2017-Hamlet-Program.Pdf

presented by Photograph by Johan Persson Running time: 3 hours 20 minutes (including a 20-minute interval) Cast, in alphabetical order Coming next Danish Soldier, Norwegian Soldier BARRY AIRD Captain, Servant EDDIE ARNOLD Horatio LEO BILL Ophelia SIÂN BROOKE Cornelius NIGEL CARRINGTON Player King RUAIRI CONAGHAN Hamlet BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Guildenstern RUDI DHARMALINGAM Priest, Messenger COLIN HAIGH Fencing Offi cial PAUL HAM Player Queen, Messenger DIVEEN HENRY Gertrude ANASTASIA HILLE Claudius CIARÁN HINDS Laertes KOBNA HOLDBROOK-SMITH Julius Caesar Ghost, Gravedigger KARL JOHNSON by William Shakespeare Polonius JIM NORTON a Bridge Theatre production Stage Manager, Offi cial AMAKA OKAFOR Barnardo DAN PARR HHHH Courtier JAN SHEPHERD ‘ A star-studded political Voltemand MORAG SILLER cataclysm for our times.’ Rosencrantz MATTHEW STEER Daily Telegraph Fortinbras SERGO VARES Marcellus DWANE WALCOTT HHHH ‘ A visceral, politically urgent tragedy.’ All other roles covered by members of the company Guardian Director LYNDSEY TURNER In cinemas from March 22 Set ES DEVLIN Find your nearest venue and book at ntlive.com Costume KATRINA LINDSAY Turn over for details of more upcoming screenings Video LUKE HALLS Lighting JANE COX Music JON HOPKINS Sound CHRISTOPHER SHUTT Great theatre needs great supporters Movement SIDI LARBI CHERKAOUI If you love NT Live, please support the National Theatre and Fights BRET YOUNT help us to continue to bring world-class theatre to cinemas. nationaltheatre.org.uk/support-the-NT Casting JULIA HORAN CDG Connect with us Subscribe to our email updates Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter ntlive.com/signup facebook.com/ntlive @ntlive Join in the conversation about tonight’s screening #HamletBarbican Upcoming broadcasts Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare a Bridge Theatre production In cinemas from March 22 HHHH ‘ Tremendously gripping.