From the Diaphragm Arches to the Ribbed Vaults. an Hypothesis for the Birth and Development of a Building Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽabbāsid Art: Squinch Fragmentation As The

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽAbbāsid Art: squinch fragmentation as The structural origin of the muqarnas La tradición sasánida en el arte ʿabbāssí: la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina como origen estructural de la decoración de muqarnas A tradição sassânida na arte abássida: a fragmentação do arco de canto como origem estrutural da decoração das Muqarnas Alicia CARRILLO1 Abstract: Islamic architecture presents a three-dimensional decoration system known as muqarnas. An original system created in the Near East between the second/eighth and the fourth/tenth centuries due to the fragmentation of the squinche, but it was in the fourth/eleventh century when it turned into a basic element, not only all along the Islamic territory but also in the Islamic vocabulary. However, the origin and shape of muqarnas has not been thoroughly considered by Historiography. This research tries to prove the importance of Sasanian Art in the aesthetics creation of muqarnas. Keywords: Islamic architecture – Tripartite squinches – Muqarnas –Sasanian – Middle Ages – ʽAbbāsid Caliphate. Resumen: La arquitectura islámica presenta un mecanismo de decoración tridimensional conocido como decoración de muqarnas. Un sistema novedoso creado en el Próximo Oriente entre los siglos II/VIII y IV/X a partir de la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina, y que en el siglo XI se extendió por toda la geografía del Islam para formar parte del vocabulario del arte islámico. A pesar de su importancia y amplio desarrollo, la historiografía no se ha detenido especialmente en el origen formal de la decoración de muqarnas y por ello, este estudio pone de manifiesto la influencia del arte sasánida en su concepción estética durante el Califato ʿabbāssí. -

Advancements in Arch Analysis and Design During the Age of Enlightenment

ADVANCEMENTS IN ARCH ANALYSIS AND DESIGN DURING THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT by EMILY GARRISON B.S., Kansas State University, 2016 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Architectural Engineering and Construction Science and Management College of Engineering KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Kimberly Waggle Kramer, PE, SE Copyright Emily Garrison 2016. Abstract Prior to the Age of Enlightenment, arches were designed by empirical rules based off of previous successes or failures. The Age of Enlightenment brought about the emergence of statics and mechanics, which scholars promptly applied to masonry arch analysis and design. Masonry was assumed to be infinitely strong, so the scholars concerned themselves mainly with arch stability. Early Age of Enlightenment scholars defined the path of the compression force in the arch, or the shape of the true arch, as a catenary, while most scholars studying arches used statics with some mechanics to idealize the behavior of arches. These scholars can be broken into two categories, those who neglected friction and those who included it. The scholars of the first half of the 18th century understood the presence of friction, but it was not able to be quantified until the second half of the century. The advancements made during the Age of Enlightenment were the foundation for structural engineering as it is known today. The statics and mechanics used by the 17th and 18th century scholars are the same used by structural engineers today with changes only in the assumptions made in order to idealize an arch. -

In the Name of the Displaced Afrin People in Shehba to the World Health Organization

الهﻻل اﻷحمر الكردي HEYVA SOR A KURD فرع عفرين ŞAXÊ EFRÎNÊ In the name of the displaced Afrin people in Shehba To the World Health Organization The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), issued a report regarding the emergence of corona virus (COVID-19) in the Syrian Republic on / 11th of March 2020 /, the report stated that the Syrian Ministry of Health confirmed the negative of all cases that were suspected and no one was infected. To counter the threat of the virus, the World Health Organization provides all means of support and assistance to the Syrian Ministry of Health to supplement its ability and preparedness to address this epidemic by providing detection and monitoring equipment, training health personnel in several governorates, and providing quarantine centers in addition to holding workshops aimed at enhancing awareness and understanding the risks of the epidemic. The report stated that the readiness of isolation centers was confirmed in / 6 / areas, namely (Damascus, Aleppo, Deir Al-Zour, Homs, Lattakia and Qamishli) and a health center is currently being established that deals with corona cases in Dwer region in the Damascus countryside. What about more than two hundred thousand displaced people in the northern countryside of Aleppo (Al-Shahba)? Through the report, we see great efforts to help the Syrians ward off the threat of this epidemic, but it is very clear that they forgot a very large geographical spot in which thousands of displaced people are present, and whose presence has reached two years, amid great disregard from the World Health Organization and the Syrian government as well. -

The Making of Seljuk Patterns on Curved Surfaces

Bridges Finland Conference Proceedings Geometric Patterns as Material Things: The Making of Seljuk Patterns on Curved Surfaces Begüm Hamzaoğlu* Architectural Design Computing Program, Istanbul Technical University Taşkışla, Taksim, Istanbul, 34437, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Mine Özkar Department of Architecture, Istanbul Technical University Taşkışla, Taksim, Istanbul, 34437, Turkey Email: [email protected] Abstract There is very little information today on the historical techniques that medieval craftsmen used to apply the intricate geometric patterns on architectural surfaces. This paper focuses on the particular problem of applying geometric patterns on curved stone surfaces and explores possible technical application scenarios for a select group of 13th century Anatolian patterns. We illustrate hypothetical processes of how to apply three patterns on three different types of curved surfaces and discuss the relation between the surface geometry and the tools. Our main motivation is to shed light on how the geometric construction of the designs and the making of these patterns correlate. Introduction Geometric patterns consisting of polygons, stars and lines were used as ornaments on monumental building façades in medieval Anatolia, also known as the Seljuk period. The style was widely common throughout the larger region at the time. The question of how these intricate designs were constructed geometrically has drawn the attention of many interdisciplinary studies [1][2][3][4]. However, only a few of these studies focus on how abstract patterns were transformed into the material things that they are whether carved into stone, tiled in brick or ceramic, or arranged in wood using special crafting techniques [5]. Materials, tools and all other components of the making process such as the craftsman’s hand movements are all factors in the formation of the shapes. -

NW Wall & Ceiling Agreement 2019

AGREEMENT between The Pacific Northwest Regional Council of Carpenters and Northwest Wall & Ceiling Contractors Association Effective June 1, 2019 - May 31, 2023 opeiu8aflcio Table of Contents Article Description Page 1 Preamble and Purpose . 1 2 Work Description . .1 3 Recognition . 5 4 Subcontractor Clause . 6 5 Effective Date and Duration . 7 6 Savings Clause . 7 7 Fringe Benefits . 8 7 .01 Health & Security . 8 7 .02 Retirement . 8 7 .02 .1 Elective Contributions . .. 9 7 .03 Apprenticeship and Training . 10 7 .04 Vacation Fund . 11 7 .05 Trust Merger . 11 8 Liability of Employers Under Funds . .. 11 9 Settlement of Disputes and Grievances . .. 14 10 Hiring . 16 10 .04 Continuing Education . 18 10 .05 Apprenticeship . 19 11 Hours of Work, Shifts & Holidays . 20 11 .01 Single Shift Operation . 20 11 .02 Multiple Shift Operation . 21 11 .03 Holidays . 23 11 .04 Rest Breaks . 23 11 .05 Meal Provisions . .. 23 Table of Contents (continued) Article Description Page 11 .06 Start Time . 23 11 .07 Overtime . 24 12 Work Rules . 24 12 .05 Shop Stewards . 26 12 .06 Tool Storage . 28 13 Safety Measures . 29 14 Travel Conditions . 30 14 .01 Zone Pay Differential . 30 14 .01 .2 General Travel Conditions . 30 14 .01 .3 Carpenters’ Zone Pay . 31 15 Committees . 33 16 Miscellaneous . 33 17 Substance Abuse Policy . 35 18 Light Duty Return to Work . 36 19 Residential Provisions . 36 20 Sick Leave Waiver . 37 Schedule A Western Washington Wages and Benefits . 38 Eastern Washington Wages & Benefits . 39 A .3 Union Dues Check-Off Assignments . 40 Handling of Hazardous Waste Materials . -

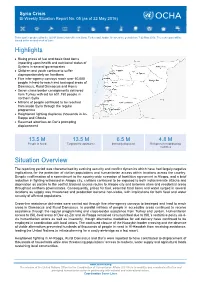

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

THE GEOMETRY of the PANTHEON's VAULT

TGS 1 THE GEOMETRY of THE PANTHEON’S VAULT Dr. Tomás García-Salgado BSArch, MSArch, PhD, UNAMprize, SNI nIII. Faculty of Architecture, National Autonomus University of México. [email protected] Website <perspectivegeometry.com> 1 Geometry of the Vault • 2 Perspective of the Vault • 3 Perspective Outline 1 Geometry of the Vault From the point of view of perspective, the only noteworthy item of the interior of the vault of the Pantheon is the visual effect produced by the geometric composition of the coffers. In order to draw the perspective outline of the interior of the Pantheon, it was essential to first understand how the vault was built, since the presence of the coffers did not arise from a decorative idea but rather from the need to reduce the weight of the vault, while maintaining a cross-section that was sufficiently robust to support its own weight. If we assume the hypothesis that the vault was built using an arched framework supported by the great cornice and set out radially, then the constructive outline of the coffers must have been controlled by means of molds built on the framework itself. In addition, it is possible that such construction was carried out at the floor level using a template that describes at least half of the hemisphere. Palladio interpreted the inside slopes of the coffered ceiling of the vault cross-section as a radial outline at the level of the great cornice (see Figure 1). In surveys subsequent to those of Palladio, as well as in recent photographic studies, it can be seen that the inferior soffit slopes of the mitered joints that form the coffered ceiling seem to be directed towards the floor, that is, the view is flush with respect to the inferior soffit planes, while the superior soffit slopes seem to follow the radial outline at the level of the cornice. -

Village of Pittsford Settled 1789 • Incorporated 1827

VILLAGE OF PITTSFORD SETTLED 1789 • INCORPORATED 1827 Members: Maria Huot Scott Latshaw Liaison: Robert Corby William McBride Attorney: Jeff Turner Lisa Cove Building Inspector: Kelly Cline Ken Morrow Recording Sec: Linda Habeeb Alternate: Ron Johnson Architectural and Preservation Review Board Regular Meeting Monday May 7, 2018 at 7:00 pm This agenda is subject to change both in number of applications, order of applications, and/or at the discretion of the Chairperson. Conflict of interest disclosure . Ken Samarra, 6 South Main Street ~ Sign . Jason Crane, 7 Stonegate Lane ~ Overhang . Jason Crane, 27 Lincoln Ave ~ Siding . Tom Dakin, 38 Rand Place ~ Lights . Robert Huot, 21 Church Street ~ Windows . Del Monte Hotel Group, 41 N. Main Street ~ Porte Cochere Member Items: Minutes: 4/2/18 Village of Pittsford documents are controlled, maintained, and available for official use on the Village of Pittsford Website, located at http://www.VillageofPittsford.org. Printed versions of this document are considered uncontrolled. Copyright © (2010) Village of Pittsford. TRANSMITTAL TRANSMITTED TO: Village of Pittsford 21 North Main Street Pittsford, New York 14534 ATTENTION: Ms. Kelly Cline VIA: Delivery DATE: April 18, 2018 RE: Architectural & Preservation Review Board Application for Exterior Renovations to the Del Monte Lodge Kelly, Attached please find the Architectural & Preservation Review Board Application and Supporting Documents for the Proposed Exterior Renovations at the Del Monte Lodge (41 North Main Street). Respectfully, Andrew Van -

C6 – Barrel Vault Country : Tunisia

Building Techniques : C6 – Barrel vault Country : Tunisia PRÉSENTATION Geographical Influence Definition Barrel vault - Horizontal framework, semi-cylindrical shape resting on load-bearing walls - For the building, use or not of a formwork or formwork supports. - Used as passage way or as roofing (in this case, the extrados is protected by a rendering). Environment One finds the barrel vault in the majority of the Mediterranean countries studied. This structure is usually used in all types of environment: urban, rural, plain, mountain or seaside. Associated floors: Barrel vaults are used for basement, intermediary and ground floors for buildings and public structures. This technique is sometimes used for construction of different floors. In Tunisia, stone barrel vaults are only found in urban environment, they are common in plains and sea side plains, exceptional in mountain. The brick barrel vault is often a standard in mountain environment. The drop vault (rear D' Fakroun) is often a standard everywhere. Associated floors: In Tunisia, this construction technique is used to build cellars, basements, cisterns (“ fesqiya ”, ground floors and first floors (“ ghorfa ”). Drop arches and brick vaults can sometimes be found on top floors. Illustrations General views : Detail close-up : This project is financed by the MEDA programme of the European Union. The opinions expressed in the present document do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Union or of its member States 1/6 C6 Tunisia – Barrel vault CONSTRUCTION PRINCIPLE Materials Illustrations Nature and availability (shape in which it is found) For the construction of barrel vaults, the most often used materials are limestone and terracotta brick in all the studied countries. -

Corporate Office Employee Analysis: Transformation from Closed Office Layout to Open Floor Plan Environment

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses from the Architecture Program Architecture Program Winter 12-1-2011 CORPORATE OFFICE EMPLOYEE ANALYSIS: TRANSFORMATION FROM CLOSED OFFICE LAYOUT TO OPEN FLOOR PLAN ENVIRONMENT Stephanie J. Fanger University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/archthesis Part of the Interior Architecture Commons, and the Other Architecture Commons Fanger, Stephanie J., "CORPORATE OFFICE EMPLOYEE ANALYSIS: TRANSFORMATION FROM CLOSED OFFICE LAYOUT TO OPEN FLOOR PLAN ENVIRONMENT" (2011). Theses from the Architecture Program. 123. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/archthesis/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses from the Architecture Program by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CORPORATE OFFICE EMPLOYEE ANALYSIS: TRANSFORMATION FROM CLOSED OFFICE LAYOUT TO OPEN FLOOR PLAN ENVIRONMENT by Stephanie Julia Fanger A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Architecture Under the Supervision of Professor Betsy S. Gabb Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2011 CORPORATE OFFICE EMPLOYEE ANALYSIS: TRANSFORMATION FROM CLOSED OFFICE LAYOUT TO OPEN FLOOR PLAN ENVIRONMENT Stephanie J. Fanger, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Betsy Gabb The office workplace within the United States has undergone monumental changes in the past century. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has cited that Americans spend an average of 90 percent of their time indoors. As human beings can often spend a majority of the hours in the day at their workplace, more so than their home, it is important to understand the effects of the built environment on the American office employee. -

Plumbing Identification and Damage Assessment Guide

Plumbing Identification and Damage Assessment Guide *Please note that not all systems will be represented exactly by these diagrams and photos. As a vendor, it is required that you familiar yourself with all types of existing systems to assure you and your company maintains vital and accurate information. Water System Identification To properly inspect the plumbing system, determine if the property has city water or well water. The below photos will assist you in determining what kind of water system the property has. Well Water Components City Water Components Plumbing Component Identification Plumbing components are items within the property that either provide or store water into the home or drain water from the home. The items that supply water to the home are kitchen and bathroom sinks, toilets, bathtubs, showers, interior and exterior faucets, hot water heater, water meter, and shutoff valves. Items that drain water from the home are drainage pipes and drainage traps. Exterior Water Meter Interior Water Meter Exterior Water Faucet Interior Water Faucet Plumbing Component Identification Continued… Water Meter Shut Off Valve Toilet Shut Off Valve Kitchen Faucet Bathroom Faucet Shower and Bathtub Toilet Plumbing Component Identification Continued… Plumbing Lines Plumbing Lines P- Trap P- Trap Refrigerator Ice Maker Line Basement Floor Drainage Plumbing Component Identification Continued… Conventional Water Heater Main Devices to Document: • Hot and Cold Water Supply Lines • Temp an d Pressure Relief Valve • Drain Va lve • Thermos tat • Gas Line Entry Point Tankless Water Heater Main Devices to Document: • Incoming Cold Water Line • Outgoing Hot Water Line Plumbing Assessment Determine the Type of Plumbing in the Property. -

The Story of Architecture

A/ft CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 062 545 193 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1992. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924062545193 o o I I < y 5 o < A. O u < 3 w s H > ua: S O Q J H HE STORY OF ARCHITECTURE: AN OUTLINE OF THE STYLES IN T ALL COUNTRIES • « « * BY CHARLES THOMPSON MATHEWS, M. A. FELLOW OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF THE RENAISSANCE UNDER THE VALOIS NEW YORK D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1896 Copyright, 1896, By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY. INTRODUCTORY. Architecture, like philosophy, dates from the morning of the mind's history. Primitive man found Nature beautiful to look at, wet and uncomfortable to live in; a shelter became the first desideratum; and hence arose " the most useful of the fine arts, and the finest of the useful arts." Its history, however, does not begin until the thought of beauty had insinuated itself into the mind of the builder.