Quincha Architecture: the Development of an Antiseismic Structural System in Seventeenth Century Lima

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bio Construction, Quincha, Thermal Performance

International Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2018, 7(2): 53-64 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijcem.20180702.01 Thermal Performance of “Quincha” Constructive Technology in a Mountainous Region Cuitiño Guadalupe1,*, Esteves Alfredo1, Barea Gustavo1, Marín Laura2, Bertini Renato3 1Environment, Habitat and Energy Institute Mendoza - CONICET, Av. Ruiz Leal s/n, Argentina 2Independent Architect, Mendoza, Argentina 3Green Village Tudunqueral Srl, Mendoza, Argentina Abstract Increasingly, families are choosing to build their homes using earth-based technologies. This is the case in Tudunqueral Ecovilla (eco village) located in Uspallata Valley, Mendoza, Argentina. In this Andes Mountain Area, the houses primarily have been built with “Quincha” (also known as “wattle and daub”). Specifically, this paper aims to evaluate the thermal performance of the eco village’s Multi-Purpose Centre (MPC) which is a “Quincha” construction. Indoor temperature and relative humidity measurements and all external variables of climate (temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation and wind speed and direction) has been registered for winter and summer seasons. Thermography to evaluate local thermal situations of walls, ceilings and floors has been used. An interesting feature is that MPC has a Trombe Wall as passive solar system for heating it. Implementing energy conservation strategies coupled with the use of “quincha” as constructive technology allow for excellent results in the face of the rigorous climate of the mountain environment. It has proven that although low outdoor temperatures of -6°C were recorded, at the same time indoor temperatures was near 10°C, that means a temperature difference (in-out) of around 16°C. As well, while outdoor thermal amplitude reached 26°C, with the optimization of the MPC the thermal range indoors was 6.25°C. -

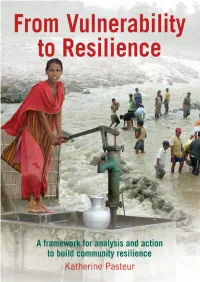

From Vulnerability to Resilience, a Framework for Analysis and Action To

From Vulnerability to Resilience PRAISE FOR THIS BOOK ‘It is rare to fi nd a book so accessible that combines theory and practice. The V2R offers a succinct yet usable framework that can be applied by a range of development actors at every level from local to national and even international.’ Nick Hall, Disaster Risk Reduction Adviser, Plan International ‘This is a very impressive and admirable piece of work. By balancing the various elements of live- lihoods, vulnerability, governance, hazards, uncertainty, resilience, it fi lls a big gap. V2R makes resilience seem more manageable.’ Dr John Twigg, Senior Research Associate, Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, University College London From Vulnerability to Resilience A framework for analysis and action to build community resilience Katherine Pasteur Practical Action Publishing Ltd Schumacher Centre for Technology and Development Bourton on Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire CV23 9QZ, UK www.practicalactionpublishing.org © Practical Action Publishing, 2011 ISBN 978 1 85339 718 9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission of the publishers. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The author has asserted her rights under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as authors of this work. Since 1974, Practical Action Publishing (formerly Intermediate Technology Publications and ITDG Publishing) has published and disseminated books and information in support of international development work throughout the world. -

Montículos Arqueológicos, Actividades Y Modos De Habitar. Vivienda Y Uso Del Espacio Doméstico En Santiago Del Estero (Tierras Bajas De Argentina)

ARQUEOLOGÍA DE LA ARQUITECTURA, 13, enero-diciembre 2016, e040 Madrid / Vitoria ISSN-L: 1695-2731 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/arq.arqt.2016.003 ESTUDIOS / STUDIES Montículos arqueológicos, actividades y modos de habitar. Vivienda y uso del espacio doméstico en Santiago del Estero (tierras bajas de Argentina) Archaeological mounds, activities and ways to inhabit. Dwellings and domestic space use in Santiago del Estero (Argentine lowlands) Constanza Taboada Instituto Superior de Estudios Sociales (ISES) del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la República Argentina (CONICET) / Instituto de Arqueología y Museo (IAM) de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (UNT) e-mail: [email protected] RESUMEN Este artículo aborda la definición del espacio habitacional de las poblaciones indígenas que vivieron en la llanura de Santiago del Estero (Argentina) y su vinculación con los montículos característicos de la región. Parte de trabajos arqueológicos de campo y pone en juego una estrategia teórico-metodológica que apunta a superar las limitaciones de una arquitectura perecedera. Como resultado se identificó un ámbito doméstico techado, con el primer registro para la región de un techo de torta y un piso posiblemente preparado. En articulación con la reinterpretación de datos bibliográficos, se definieron situaciones diferenciadas en cuanto a actividades, construcciones y modos de habitar, que habilitan una nueva lectura sobre la diversidad y características de las poblaciones de la región. Los casos analizados amplían el conocimiento de la diversidad y distribución de las construcciones monticulares de las tierras bajas de Sudamérica, y aportan elementos sobre arquitectura doméstica, poco estudiada para los mismos. Palabras clave: arqueología de unidades domésticas; arquitectura; estratigrafía; prehispánico; colonial; tierras bajas sudamericanas. -

C6 – Barrel Vault Country : Tunisia

Building Techniques : C6 – Barrel vault Country : Tunisia PRÉSENTATION Geographical Influence Definition Barrel vault - Horizontal framework, semi-cylindrical shape resting on load-bearing walls - For the building, use or not of a formwork or formwork supports. - Used as passage way or as roofing (in this case, the extrados is protected by a rendering). Environment One finds the barrel vault in the majority of the Mediterranean countries studied. This structure is usually used in all types of environment: urban, rural, plain, mountain or seaside. Associated floors: Barrel vaults are used for basement, intermediary and ground floors for buildings and public structures. This technique is sometimes used for construction of different floors. In Tunisia, stone barrel vaults are only found in urban environment, they are common in plains and sea side plains, exceptional in mountain. The brick barrel vault is often a standard in mountain environment. The drop vault (rear D' Fakroun) is often a standard everywhere. Associated floors: In Tunisia, this construction technique is used to build cellars, basements, cisterns (“ fesqiya ”, ground floors and first floors (“ ghorfa ”). Drop arches and brick vaults can sometimes be found on top floors. Illustrations General views : Detail close-up : This project is financed by the MEDA programme of the European Union. The opinions expressed in the present document do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Union or of its member States 1/6 C6 Tunisia – Barrel vault CONSTRUCTION PRINCIPLE Materials Illustrations Nature and availability (shape in which it is found) For the construction of barrel vaults, the most often used materials are limestone and terracotta brick in all the studied countries. -

No. 28393-A Gaceta Oficial Digital, Martes 24 De Octubre De 2017 1 No

No. 28393-A Gaceta Oficial Digital, martes 24 de octubre de 2017 1 No. 28393-A Gaceta Oficial Digital, martes 24 de octubre de 2017 2 No. 28393-A Gaceta Oficial Digital, martes 24 de octubre de 2017 3 No. 28393-A Gaceta Oficial Digital, martes 24 de octubre de 2017 4 N° RUC NOMBRE 200001 1946328-1-730987 PUENTE HOMBRE INC 200002 1404708-1-628668 PUENTE INTEROCEANICO CORP 200003 1254337-1-593980 PUENTE NUEVO S A 200004 557725-1-444493 PUENTE TERRESTRE INTEROCEANICO DE GUATEMALA S A 200005 1736696-1-693515 PUENTECOM S A 200006 1132217-1-567403 PUENTEDEY HOLDING CORP 200007 1925690-1-727154 PUENTES & PAZ S A 200008 1632763-1-672175 PUENTES MARITIMOS LTD INC 200009 644659-1-458767 PUENTES MEDIA SOLUTIONS S A 200010 2240483-1-779636 PUENTES Y COMPONENTES S A 200011 1333660-1-613507 PUENTES Y DRAGADOS DE PANAMA S A 200012 1341869-1-615188 PUERCOMER S A 200013 1427913-1-633491 PUERTA A PUERTA S A 200014 1210710-1-584251 PUERTA DE SAN VICENTE S A 200015 1038922-1-544557 PUERTA NUEVA CO S A 200016 451-484-101603 PUERTA NUEVA, S.A. 200017 1212669-1-584681 PUERTA SUR S A 200018 1459573-1-639647 PUERTA Y PERSINA S A 200019 2565688-1-828585 PUERTAS AL OCEANO S A 200020 1881003-1-719109 PUERTAS BETHEL S A 200021 2507309-1-819820 PUERTAS PORTONES PANAMA S A 200022 2096506-1-756044 PUERTAS Y ACABADOS DEL MUNDO S A 200023 1590203-1-664247 PUERTAS Y VENTANAS CATHERINE S A 200024 865379-1-507913 PUERTO ANTIGUO S A 200025 849599-1-505064 PUERTO ARMUELLES ADVENTURE CORP 200026 2553983-1-826691 PUERTO ARMUELLES CONCEPTS S A 200027 1801676-1-705391 PUERTO AZUL -

The Basilica of Maxentius

STRUCTURAL APPRAISAL OF A ROMAN CONCRETE VAULTED MONUMENT: THE BASILICA OF MAXENTIUS A. Albuerne1 and M.S. Williams2 1 Dr Alejandra Albuerne Arup Advanced Technology and Research 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ UK Tel: +44 20 7755 4446 [email protected] 2 Prof. Martin S. Williams (corresponding author) University of Oxford Department of Engineering Science Parks Road Oxford OX1 3PJ UK Tel: +44 1865 273102 [email protected] RUNNING HEAD: Basilica of Maxentius Page 1 ABSTRACT The Basilica of Maxentius, the largest vaulted space built by the Romans, comprised three naves, the outer ones covered by barrel vaults and the central, highest one by cross vaults. It was built on a sloping site, resulting in a possible structural vulnerability at its taller, western end. Two naves collapsed in the Middle Ages, leaving only the barrel vaults of the north nave. We describe surveys and analyses aimed at creating an accurate record of the current state of the structure, and reconstructing and analysing the original structure. Key features include distortions of the barrel vaults around windows and rotation of the west wall due to the thrust from the adjacent vault. Thrust line analysis results in a very low safety factor for the west façade. The geometry of the collapsed cross vaults was reconstructed from the remains using solid modelling and digital photogrammetry, and thrust line analysis confirmed that it was stable under gravity loads. A survey of the foundations and earlier structures under the collapsed south-west corner revealed horizontal slip and diagonal cracking in columns and walls; this is strong evidence that the site has been subject to seismic loading which may have caused the partial collapse. -

The Art of Framing Catalog

THE ART OF FRAMING CATALOG Dome Ceilings • Groin Vaults • Cove Ceilings • Barrel Vaults & MORE! We Create Curve Appeal If you’ve ever admired the elegance of an archway or sat in awe of an arched ceiling, but weren’t sure if such a project would fall within your budget – you’ve found your solution. Archways and arched ceilings have historically been skill-dependent, costly and very time consuming. Well, we’ve got good news for you… cost is not an issue any more! Our prefab archway and ceilings systems are designed for PROs, but easy enough for DIYers. The production process eliminates the need for skill at installation, making these systems affordable and easy to implement. We’re your direct archways and ceilings manufacturer, so no retail markup, and we’ll produce to your field measurements. Plus, we’ve got the nation covered. We have manufacturing plants in Anaheim, CA, Dallas/Fort Worth, TX & Atlanta, GA. You’ll work directly with us from start to finish. No middleman. No markup. This means you always get the best price and customer service. All of our archway and ceilings kits are made to your specs. Worried about lead times? Most archway and ceiling kits are built within 3 -5 business days, from here we’re ready to ship your archways and ceiling kits directly to your jobsite. Ready for the best part? Because we have the tools and staffing to adapt to your needs in a flash, our prices will leave you smiling. Visit any of our product pages online and use our pricing calculator or look over our pricing table to see for yourself. -

Limiting the Use of Centering in Vaulted Construction:The Early

Limiting the Use of Centering in Vaulted Construction: The Early Byzantine Churches of West Asia Minor Nikolaos Karydis Introduction The evolution of ecclesiastical architecture during the Early Byzantine period was marked by a major development in construction technology: the gradual transition from the building system of the “timber-roof basilica” to the one of the vaulted church. The early stages of this development seem to date back to the period between the late 5th and the 7th century AD and some of its earliest manifestations occur in the vaulted monuments of Constantinople and west Asia Minor. If the former are well-studied, the role of west Asia Minor in the development of vaulted church architecture is often underestimated, despite the publications of Auguste Choisy (1883), Hans Buchwald (1984), and others on this topic. Still, the published archaeological evidence from the cities of this area is clear: in Ephesos, Priene and Pythagorion, ambitious building programs were launched to replace timber-roof basilicas by magnificent domed churches.1 By the end of the 6th century, major vaulted monuments had already made their appearance in the civic centers of Sardis, Hierapolis, and Philadelphia.2 (Fig. 1) The plethora of Early Byzantine vaulted churches in the west coastal plains and river valleys of Asia Minor indicates that monumental architecture in this region was strongly influenced by the new architectural vocabulary. (Fig. 2) This development changed radically the way in which churches were designed. The use of vaults, and, in particular, domes, called for load-bearing systems that were profoundly different from the ones of the timber-roof basilica. -

Persian Vaulted Architecture: Morphology and Equilibrium of Vaults Under Static and Dynamic Loads

Transactions on the Built Environment vol 15, © 1995 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 Persian vaulted architecture: morphology and equilibrium of vaults under static and dynamic loads A. Chassagnoux Laboratoire Informatique et Structures, Ecole d'Architecture, Rue Massenet 44300-Nantes, France Abstract Persia has created an original monumental vaulted architecture, whose morphology replies to spiritual and technical imperatives, sometimes contradictory. The analysis of calculations to finite elements undertaken on several models of vaults, under dynamic and static loads, allows us to specify the evolution of techniques of vaulting of the Persian architecture in the course of centuries, and to test the empirical solution pertinence used. 1 Specificity of the Persian vaulted architecture Pre-Islamic Persia has created an original monumental vaulted architecture. Its architectural forms reply essentially to two imperatives: a technical imperative and a spiritual imperative. From a technical point of view, the Iranian geographical space being often arid and lacking of wood, builders have perfected vault techniques especially in bricks, cooked or unfired and more rarely, in stones built without using centerings. These vaults had furthermore to guarantee as far as possible a suitable resistance to frequent earthquakes in the region. From a spiritual point of view, symbols linked to the space have determined an original architectural morphology. In the tradition of antic Persia, the square is the symbol of the terrestrial world, it represents the four cardinal points corresponding to the four directions of terrestrial space, the four elements of the matter: the earth, the air, the water and the fire, the four seasons, etc.. -

Posthumanism, New Materialism and Feminist Media Art

Posthumanism, New Materialism and Feminist Media Art María Fernández Cornell University [email protected] Abstract process of change. Consequently this subjectivity is Some scholars understand the theoretical orientations of chaotic rather than in control, distributed rather than posthumanism and new materialisms to be in tension if not in autonomous and located in consciousness. [4] In more distinct opposition to previous feminisms. This essay explores recent work she posits that in our era, digital technologies select works by two contemporary artists to suggest that are integrated in our daily lives and communications posthumanism and new materialism have antecedents in infrastructure to such a great extent that we have evolved previous feminist media arts. This proposition encourages the recognition of feminist contributions to the history of with them and it is difficult to differentiate human from posthumanist and post anthropocentric art practices. nonhuman agencies. [5] Similarly, the philosopher Rosi Braidotti Introduction associates humanism with a universalizing notion of the subject (white, male, able bodied), and proposes a critical posthumanism with special attention to subjectivity. Her The work of women artists working with technology is critical posthuman subject is relational, constituted in and poorly represented in the art historical record. [1] Even by multiplicity and is simultaneously embodied and today when both digital media and feminism have located, not only geographically, but also affectively become popular, few publications about this art exist. along hierarchies or gender, race and class. Critical The paucity of recognition in the art world posthumanism for her involves interconnections between notwithstanding, new media art by women continuously humans, nonhumans, and the environment as well as the proliferates. -

Construction Manual for Earthquake-Resistant Houses Built Of

Gernot Minke Construction manual for earthquake-resistant houses built of earth Published by GATE - BASIN (Building Advisory Service and Information Network) at GTZ GmbH (Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit) P.O.Box 5180 D-65726 Eschborn Tel.: ++49-6196-79-3095 Fax: ++49-6196-79-7352 e-mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.gtz.de/basin December 2001 Contents Acknowledgement 4 Introduction 5 1. General aspects of earthquakes 6 1.1 Location, magnitude, intensity 6 1.2 Structural aspects 6 2. Placement of house in the case of 8 slopes 3. Shape of plan 9 4. Typical failures, 11 typical design mistakes 5. Structural design aspects 13 6. Rammed earth walls 14 6.1 General 14 6.2 Stabilization through mass 15 6.3 Stabilization through shape of16 elements 6.4 Internal reinforcement 19 7. Adobe walls 22 7.1 General 22 7.2 Internal reinforcement 24 7.3 Interlocking blocks 26 7.4 Concrete skeleton walls with 27 adobe infill 8. Wattle and daub 28 9. Textile wall elements filled with 30 earth 10. Critical joints and elements 34 10.1 Joints between foundation, 34 plinth and wall 10.2 Ring beams 35 10.3 Ring beams which act as roof support 36 11. Gables 37 12. Roofs 38 12.1 General 38 12.2 Separated roofs 38 13. Openings for doors and windows 41 14. Domes 42 15. Vaults 46 16. Plasters and paints 49 Bibliographic references 50 3 Acknowledgement This manual was first published in Spanish within the context of the research and development project Viviendas sismorresistentes en zonas rurales de los Andes, supported by the German organizations Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn (DFG), and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn (gtz). -

Análisis De Microhuellas De Uso Mediante Microscopio Electrónico

Revista de Antropología N° 26, 2do Semestre, 2012: 129-150 Análisis de Microhuellas de Uso Mediante Microscopio Electrónico de Barrido (MEB) de Artefactos Óseos de un Sitio Arcaico Tardío del Valle de Mauro (Región de Coquimbo, Chile): Aportes para una Reconstrucción Contextual Use-Wear Analysis Through Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) of Bone Tools from a Late Archaic Site in the Mauro Valley (Coquimbo Region, Chile): Contributions to a Contextual Reconstruction. Boris Santanderi y Patricio López M.ii Resumen Este trabajo presenta los resultados del análisis mediante Microscopio Electrónico de Barrido (MEB) realizado sobre siete artefactos óseos provenientes del sitio Arcaico Tardío (c.a. 4000-2000 a.p.) MAU085 (31º 57´S – 71º 01´O, Región de Coquimbo, Chile). Este análisis tuvo por objetivos identificar funcionalidades de un conjunto de artefactos óseos diversos y sus relaciones con la variedad de morfologías identificadas. Asimismo, se buscó relacionar los artefactos óseos con las evidencias artefactuales y ecofactuales, específicamente los restos líticos, ya que la hipótesis inicial de la funcionalidad de los artefactos óseos del sitio refiere su uso a herramientas para la talla y reavivado de bordes de puntas de proyectil y artefactos de corte. El análisis mediante Microscopio Electrónico de Barrido indica que los artefactos óseos fueron usados tanto en líticos así como en restos blandos como pieles y fibras textiles ampliando el uso de artefactos tradicionalmente asignados a retocadores. Palabras clave: Microscopio Electrónico de Barrido, Artefactos óseos, Arcaico Tardío, Norte Semiárido, Chile. i Grupo Quaternário e Pré-História do Centro de Geociências (uID 73 - FCT Portugal), Portugal. Programa de Doctorado en Cuaternario y Prehistoria, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, España.