“In Autumn Our Horses Are Well-Fed and Ready for Action” – the Ch'ing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines Caitlin Castaneda 1 , Rytis Juras 1, Anas Khanshour 2, Ingrid Randlaht 3, Barbara Wallner 4, Doris Rigler 4, Gabriella Lindgren 5,6 , Terje Raudsepp 1,* and E. Gus Cothran 1,* 1 College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2 Sarah M. and Charles E. Seay Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, Dallas, TX 75219, USA 3 Estonian Native Horse Conservation Society, 93814 Kuressaare, Saaremaa, Estonia 4 Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 75007 Uppsala, Sweden 6 Livestock Genetics, Department of Biosystems, KU Leuven, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (E.G.C.) Received: 9 August 2019; Accepted: 13 August 2019; Published: 20 August 2019 Abstract: The Estonian Native Horse (ENH) is a medium-size pony found mainly in the western islands of Estonia and is well-adapted to the harsh northern climate and poor pastures. The ancestry of the ENH is debated, including alleged claims about direct descendance from the extinct Tarpan. Here we conducted a detailed analysis of the genetic makeup and relationships of the ENH based on the genotypes of 15 autosomal short tandem repeats (STRs), 18 Y chromosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mitochondrial D-loop sequence and lateral gait allele in DMRT3. -

Harvard Polo Asia by Abigail Trafford

Horsing Around IN THE HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS OF POLO IN ASIA We all meet up during the six-hour stopover in the Beijing Airport. The invitation comes from the Genghis Khan Polo Club to play in Mongolia and then to head back to China for a university tournament at the Metropolitan Polo Club in Tianjin. Say, what? Yes, polo! Both countries are resurrecting the ancient sport—a tale of two cultures—and the Harvard players are to be emissaries to help generate a new ballgame in Asia. In a cavernous airport restaurant, I survey the Harvard Polo Team: Jane is captain of the women’s team; Shawn, captain of the men’s team; George, the quiet one, is a physicist; Danielle, a senior is a German major; Sarah, a biology major; Aemilia writes for the Harvard Crimson. Marina, a mathematician, will join us later. Neil and Johann are incoming freshmen; Merrall, still in high school, is a protégé of the actor Tommy Lee Jones—the godfather of Harvard polo. And where are the grownups? Moon Lai, a friend of Neil’s parents, is the photographer from Minnesota. Crocker Snow, Harvard alum and head of the Edward R. Murrow Center at Tufts, is tour director and coach. I am along as cheer leader and chronicler. We stagger onto the late-night plane to Ulan Bator (UB), the capital of Mongolia, pile into a van and drive into the darkness—always in the constant traffic of trucks. Our first camp of log cabins is near an official site of Naadam—Mongolia’s traditional summer festival of horse racing, wrestling and archery. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Nomadic Incursion MMW 13, Lecture 3

MMW 13, Lecture 3 Nomadic Incursion HOW and Why? The largest Empire before the British Empire What we talked about in last lecture 1) No pure originals 2) History is interrelated 3) Before Westernization (16th century) was southernization 4) Global integration happened because of human interaction: commerce, religion and war. Known by many names “Ruthless” “Bloodthirsty” “madman” “brilliant politician” “destroyer of civilizations” “The great conqueror” “Genghis Khan” Ruling through the saddle Helped the Eurasian Integration Euroasia in Fragments Afro-Eurasia Afro-Eurasian complex as interrelational societies Cultures circulated and accumulated in complex ways, but always interconnected. Contact Zones 1. Eurasia: (Hemispheric integration) a) Mediterranean-Mesopotamia b) Subcontinent 2) Euro-Africa a) Africa-Mesopotamia 3) By the late 15th century Transatlantic (Globalization) Africa-Americas 12th century Song and Jin dynasties Abbasids: fragmented: Fatimads in Egypt are overtaken by the Ayyubid dynasty (Saladin) Africa: North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa Europe: in the periphery; Roman catholic is highly bureaucratic and society feudal How did these zones become connected? Nomadic incursions Xiongunu Huns (Romans) White Huns (Gupta state in India) Avars Slavs Bulgars Alans Uighur Turks ------------------------------------------------------- In Antiquity, nomads were known for: 1. War 2. Migration Who are the Nomads? Tribal clan-based people--at times formed into confederate forces-- organized based on pastoral or agricultural economies. 1) Migrate so to adapt to the ecological and changing climate conditions. 2) Highly competitive on a tribal basis. 3) Religion: Shamanistic & spirit-possession Two Types of Nomadic peoples 1. Pastoral: lifestyle revolves around living off the meat, milk and hides of animals that are domesticated as they travel through arid lands. -

Supplement 1999-11.Pdf

Ìàòåðèàëû VI Ìåæäóíàðîäíîãî ñèìïîçèóìà, Êèåâ-Àñêàíèÿ Íîâà, 1999 ã. 7 UDC 591 POSSIBLE USE OF PRZEWALSKI HORSE IN RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT OF AN ECOSYSTEM OF UKRAINIAN STEPPE – A POTENTIAL PROGRAM UNDER LARGE HERBIVORE INITIATIVE WWF EUROPE Akimov I.1, Kozak I.2, Perzanowski K.3 1Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2Institute of the Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 3International Centre of Ecology, Polish Academy of Sciences Âîçìîæíîå èñïîëüçîâàíèå ëîøàäè Ïðæåâàëüñêîãî â âîññòàíîâëåíèè è â óïðàâëåíèè ýêîñèñòåìîé óê- ðàèíñêèõ ñòåïåé êàê ïîòåíöèàëüíàÿ ïðîãðàììà â èíèöèàòèâå WWE Åâðîïà “êðóïíûå òðàâîÿäíûå”. Àêèìîâ È., Êîçàê È., Ïåðæàíîâñêèé Ê. –  ñâÿçè ñ êëþ÷åâîé ðîëüþ âèäîâ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ æèâîòíûõ â ãàðìîíèçàöèè ýêîñèñòåì ïðåäëàãàåòñÿ øèðå èñïîëüçîâàòü åäèíñòâåííûé âèä äèêîé ëîøàäè — ëîøàäü Ïðæåâàëüñêîãî – â ïðîãðàìíîé èíèöèàòèâå Âñåìèðíîãî ôîíäà äèêîé ïðèðîäû â Åâðîïå (LHF WWF). Êîíöåïöèÿ èñïîëüçîâàíèÿ ýòîãî âèäà êàê èíñòðóìåíòà âîññòàíîâëåíèÿ è óïðàâëåíèÿ â ñòåïíûõ ýêîñèñòåìàõ â Óêðàèíå õîðîøî ñîîòâåòñòâóåò îñíîâíîé íàïðàâëåííîñòè LHJ WWF: à) ñîõðàíåíèè ëàíäøàôòîâ è ýêîñèñòåì êàê ìåñò îáèòàíèÿ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ á) ñî- õðàíåíèå âñåõ êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ â âèäå æèçíåñïðîñîáíûõ è øèðîêîðàñïðîñòðàíåííûõ ïîïóëÿ- öèé â) ðàñïðîñòðàíåíèå çíàíèé î êðóïíûõ òðàâîÿäíûõ ñ öåëüþ óñèëåíèÿ áëàãîïðèÿòíîãî îòíîøå- íèÿ ê íèì ñî ñòîðîíû íàñåëåíèÿ. Íàìå÷åíû òåððèòîðèè ïîòåíöèàëüíî ïðèãîäíûå äëÿ èíòðîäóê- öèè ýòîãî âèäà. The large part of Eurasia is undergoing now considerable economic and land use changes, which brings a threat to some endangered populations or even species, but on the other hand creates new opportunities for ecological restoration of former wilderness areas. Large herbivores are key species for numerous ecosystems being the link between producers (vegetation), and secondary consumers (predators), including people. -

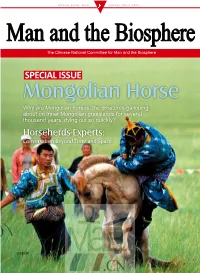

Mongolian Horse Why Are Mongolian Horses, the Creatures Galloping About on Inner Mongolian Grasslands for Several Thousand Years, Dying out So Quickly?

SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 Man and the Biosphere Man and the Biosphere The Chinese National Committee for Man and the Biosphere SPECIAL ISSUE Mongolian Horse Why are Mongolian horses, the creatures galloping about on Inner Mongolian grasslands for several thousand years, dying out so quickly? Horseherds-Experts: Conversation Beyond Time and Space A home on the grassland. Photo: Ayin SPECIAL SPECIAL ISSUE 2010 Postal Distribution Code:82-253 Issue No.:ISSN 1009-1661 CN11-4408/Q US$5.00 The Silingol Grassland. Photo: He Ping Photo: The Silingol Grassland. This oil painting dates from 1986. The boy is called Chog and he is about 14 or 15 years old. This is about the time when livestock were starting to be distributed among individual households, just before the privatization of pasturelands. Now, 20 years later, the situation on the grasslands is very worrying. Desertification is largely caused by over-development and over-grazing. In the old days, the traditional nomadic way of life did no harm to the grasslands, now it has been replaced with privatized farms, the grassland is degenerating. Text and photo: Chen Jiqun (an artist specializing in oil painting and depicting grassland scenes. He lived in Juun Ujumucin, Silin ghol aimag (league), for 13 years from 1967) The Mongolian Horse – Taking us on a Long Journey Our editing team There are, perhaps, only a few animals in the world that are as deeply embedded into a culture as is the Mongolian Horse. This is an animal whose fate is so closely tied to a people that its situation is an indicator of both the health of the external environment and the culture upon which it relies. -

The Caspian Horse of Iran

THE CASPIAN HORSE OF IRAN by Louise Firouz PREFACE Several years ago word spread that a new breed of horse, like a miniature Arabian. had been found on the shores of the Caspian in Iran. In 1965 five Caspian ponies were brought to Louise Firouz in Tehran for riding by her children. Louise Firouz was born in Washington, graduated at Cornell where she studied animal husbandry. classics, and English. In ) '157 she married Narcy Firouz and moved to Tehran where she is occupied in farming and raising horses. Following the arrival of the five Caspians, a three-year survey was begun to search for more of these horses. She covered part of an area from Astara to Pahlevi-Dej located east of the Caspian. About :0 ponies are estimated to live between Babol and Amol (Map 1). Six mares and five stallions were brought to the breeding farm at Norouzabad near Tehran. In 1966 a stud book was established to encourage purity 'Of the strain. Dr. Hosseinion, Tehran Veterinary College, regularly inspects foals and adults. The similarity between the Caspian and the horses pulling the chariot of Darius and the ponies on a bas-relief at Persepolis is significant. The above has been summarized from the illustrated article by Louise Firouz in Animals, June, 1970 (see Bibliography). My interest in horses ancient and modem stems from the Equidtze excavated at Kish, eight miles east of Babylon, by the Field Museum-Oxford University Joint Expedition to Iraq, 1923-34. In 1928 I was one of the Staff members of this Expedition under Field Director Louis Charles Watelin. -

LIBRO El Imperio Mongol.Indb

EL IMPERIO MONGOL Temas de Historia Medieval Coordinador: JOSÉ MARÍA MONSALVO ANTÓN EL IMPERIO MONGOL Antonio García Espada Consulte nuestra página web: www.sintesis.com En ella encontrará el catálogo completo y comentado © Antonio García Espada © EDITORIAL SÍNTESIS, S. A. Vallehermoso, 34. 28015 Madrid Teléfono: 91 593 20 98 www.sintesis.com ISBN: 978-84-9171-051-6 Depósito Legal: M-29.570-2017 Impreso en España - Printed in Spain Reservados todos los derechos. Está prohibido, bajo las sanciones penales y el resarcimiento civil previstos en las leyes, reproducir, registrar o transmitir esta publicación, íntegra o parcialmente, por cualquier sistema de recuperación y por cualquier medio, sea mecánico, electrónico, magnético, electroóptico, por fotocopia o por cualquier otro, sin la autorización previa por escrito de Editorial Síntesis, S. A. ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN . 11 PARTE I CHINGGIS KHAN (1162-1227) 1. LA HISTORIA SECRETA DE LOS MONGOLES . 23 1 .1 . Temuyin . 24 1 .1 .1 . Yesugei . 25 1 .1 .2 . Hoelun . 26 1 .1 .3 . La estepa . 27 1 .1 .4 . El despertar de Temuyin . 30 1 .1 .5 . El rapto de Borte . 32 1 .1 .6 . La guerra contra Jamuqa . 33 1 .1 .7 . La victoria sobre los keraítas . 35 1 .1 .8 . La victoria sobre los naimanos . 36 1 .2 . LaHistoria secreta . 38 1 .2 .1 . La datación de la Historia secreta . 39 1 .2 .2 . Fuentes alternativas . 40 1 .2 .3 . Composición literaria . 41 1 .2 .4 . Cosmovisión de la Historia secreta . 42 2. EL IMPERIO DE CHINGGIS KHAN . 45 2 .1 . La conquista del mundo sedentario . 45 2 .1 .1 . -

The Development of Mongol Identity in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Witness

■ Source: Itinerario 24:2 (2000), pp. 44–61. THE DEVELOPMENT OF MONGOL IDENTITY IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries witnessed the development of a Mongol identity. The Mongol conquests in the thirteenth century had laid the foundations but had not truly forged such an identity. These earlier events provided, in modern parlance, the cultural memory that eventu- ally served to unify them. However, the Mongol Empire actually revealed the fractiousness of the Mongols and their inability to promote the unity that might gradually have fostered a Mongol identity. As Joseph Fletcher argued, the creation of a supra-tribal identity for nomadic herders has proven to be extremely difficult.1 The so-called Mongol Empire attested to this predicament, as within two generations it evolved into four separate Khanates, which occasionally waged war against each other. For example, individual Khanates frequently sided with non-Mongols against fellow Mongols. In addition, the military, the quintessential Mongol institution, was not, as the Empire expanded, composed simply of Mongols. Turks, Persians, and even Chinese served in and sometimes led the Mongol armies, contributing to the blurring of Mongol identity. The glorious successes of the Mongol Empire offered later Mongols solace and the model of a great historical legacy. During the Ming era, different leaders, Esen in the fifteenth century and the Dayan Khan in the sixteenth century, sought to unify the Mongols, but both failed to elicit suf- ficient support.2 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, faced with threats to their lands and to their very existence, the Mongols repeatedly sought to identify with heroes of the past, an effort that was significant in inspiring bonds of identity. -

Chinggis Khan and His Conquest of Khorasan: Causes and Consequences

CHINGGIS KHAN AND HIS CONQUEST OF KHORASAN: CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES BY ANIBA ISRAT ARA ARSHAD ISLAM INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA ABSTRACT This book explores the causes and consequences of Chinggis Khan’s invasion of Khorasan in the 13th century. It discusses Chinggis Khan’s charismatic leadership qualities that united all nomadic tribes and gave him the authority to become the supreme Mongol leader, which helped him to invade Khorasan. It also focuses on the rise of the Muslim cities in Khorasan where many Muslim scholars kept their intellectual brilliance and made Khorasan the cultural capital of the Muslims. This study apprises us of Chinggis Khan’s war tactics and administrative system which made his men extremely strong and advanced despite their culture remaining barbaric in nature. His progeny also followed a similar policy for a long time until all Muslim cities were fully destroyed. The work also focuses on the rise of many sectarian divisions among the Muslims which brought disunity that eventually led to their downfall. Thus, this study underscores the importance of revitalization of unity in the Muslim world so that Muslims may not become vulnerable to any foreign imperialistic power. Unity also is the key to preserve Muslim intellectual thought and Islamic cultural identities. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the beginning, I would like to say that all praise is to Allah (swt) Almighty; despite the difficulties, with His mercy, and the strength, patience and resilience that He has bestowed on me, I completed my work. I am heartily thankful to my beloved supervisor to Dr. Arshad Islam, whose encouragement, painstaking supervision and tireless motivating from the beginning of my long journey to the concluding level helped me to complete this study. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

I HISTORICAL PROLOGUE The Land and the People Demchugdongrob, commonly known as De Wang (Prince De in Chinese), was a thirty-first generation descendant of Chinggis Khan and the last ruler of Mongolia from the altan urag, the Golden Clan of the Chinggisids. The only son of Prince Namjilwang- chug, Demchugdongrob was bom in the Sunid Right Banner of Inner Mongolia in 1902 and died in Hohhot, the capital of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, in 1966. The Sunid was one of the tribes that initially supported Chinggis Khan (r. 1206- 1227). In the sixteenth century, Dayan Khan reunified Mongolia and put this tribe under the control of his eldest son, Torubolod. Thereafter, the descendants of Torubolod be came the rulers not only of the Sunid but also of the Chahar (Chakhar), Ujumuchin, and Khauchid tribes. The Chahar tribe was always under the direct control of the khan him self During the Manchu domination, the Sunid was divided into the Right Flank and Left Flank Banners, and both were part of the group of banners placed under the Shilingol League. During the first half of the seventeenth century, the Manchus expanded to the southern parts of Manchuria and began to compete with the Ming Chinese. Realizing the danger in the rise of the Manchus, Ligdan Khan, the last Mongolian Grand Khan, aban doned his people ’s traditional hostility toward the Chinese and formed an alliance with the Ming court to fight the Manchus. Although this policy was prudent, it was unaccept able to most Mongolian tribal leaders, who subsequently rebelled and joined the Manchu camp. -

The Fate of Medical Knowledge and the Neurosciences During the Time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire

Neurosurg Focus 23 (1):E13, 2007 The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire SAM SAFAVI-ABBASI, M.D., PH.D.,1 LEONARDO B. C. BRASILIENSE, M.D.,2 RYAN K. WORKMAN, B.S.,2 MELANIE C. TALLEY, PH.D.,2 IMAN FEIZ-ERFAN, M.D.,1 NICHOLAS THEODORE, M.D.,1 ROBERT F. SPETZLER, M.D.,1 AND MARK C. PREUL, M.D.1 1Division of Neurological Surgery, Neurosurgery Research; and 2Spinal Biomechanics Laboratory, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona PIn 25 years, the Mongolian army of Genghis Khan conquered more of the known world than the Roman Empire accomplished in 400 years of conquest. The recent revised view is that Genghis Khan and his descendants brought about “pax Mongolica” by securing trade routes across Eurasia. After the initial shock of destruction by an unknown barbaric tribe, almost every country conquered by the Mongols was transformed by a rise in cultural communication, expanded trade, and advances in civiliza- tion. Medicine, including techniques related to surgery and neurological surgery, became one of the many areas of life and culture that the Mongolian Empire influenced. (DOI: 10.3171/FOC-07/07/E13) KEY WORDS • Avicenna • Genghis Khan • history of neuroscience • Mongolian empire • Persia EPORTS ABOUT THE HISTORY of medicine in Asia are golica” and secured the fabled trade routes between scarce. This article provides an overview of the fate Europe and eastern China known as the Silk Road.8,23 R of Asian medicine, specifically Persian, Indian, and After the initial shock and destruction associated with Chinese scientific, neurological, and surgical knowledge invasion by an unknown barbaric tribe, almost every before and during the Mongolian invasion and hegemony.